The following was one of a dozen or more profusely illustrated pieces that I wrote for a London periodical in 1982 called The Movie, specifically for issue no. 117; some of these articles were later recycled into a series of coffee-table books devoted to various decades in film history, but not this one, which I’ve slightly revised for its reappearance here.

Even though this short piece is somewhat dated now, I’m reviving it to celebrate Criterion’s awesome edition of Lonesome on DVD and blu-Ray (in the best print of the film I’ve ever seen, with a superb audio commentary by Richard Koszarski), along with Fejos’s subsequent The Last Performance and Broadway on a separate disc. For me, this is unquestionably one of Criterion’s most impressive releases to date. — J.R.

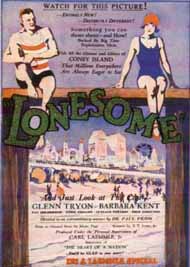

LONESOME

In a large, lonely city, the daily routines of two ordinary people who do not know one another are shown in parallel development. First Mary and then Jim wakes up, dresses and has breakfast (at the same restaurant). They proceed to their separate jobs in the same plant.

It is July 3, the day before Independence Day, and after the holiday starts at noon both characters turn down invitations to join couples, and go home alone. But a passing music van advertising the Coney Island fair convinces them both to take a bus there, and the two finally meet on the beach.

After spending the rest of the day together and falling in love, they become separated in a roller-coaster ride, and lose each other in the ensuing panic after Mary’s car catches fire and Jim is arrested. Later, they search in vain for each other, and finally go home in miserable defeat — where they discover to their amazement that they are next-door neighbors.

Directed by Paul Fejos, 1928

Prod co: Jewel for Universal. prod: Carl Laemmle. sc: Edward T. Lowe Jr. from a story by Mann Page. titles and dial: Tom Reed. photo (including tinted and color sequences): Gilbert Warrenton. ed: Frank Atkinson. length: 6785 ft. (approx 90 minutes).

Cast: Barbara Kent (Mary), Glenn Tryon (Jim), Fay Holderness (overdressed woman), Gustav Partos (romantic gent), Eddie Phillips (the sport).

It has often been said that the art of the silent film achieved a certain perfection of expression immediately before sound came in and made that art a thing of the past. Lonesome is, in many ways, a classic example of this.

Paul Fejos’ film is a near-perfect amalgam of American filmmaking technique and energy combined with a rich heritage of European influences — ranging from French impressionism through German Expressionism to the techniques of montage developed by the Russians. Such related poetic, big-city films of the late Twenties as Fritz Lang’s Metropolis, Walter Ruttmann’s Berlin, Symphony of a Great City, F.W. Murnau’s Sunrise (all 1927), and King Vidor’s The Crowd (1928) all helped to establish part of its background. But Lonesome testifies to an internationally sophisticated visual language that few other movies of the period can equal. At the same time, it dramatically illustrates the problems incurred in changing from silent film to sound.

Significantly, Lonesome is available in three separate versions today. A sound version has the advantage of enhancing the viewer’s sense of city bustle (traffic and crowds) through its sound effects, while the use of music actually becomes central to the plot in the final scene. When the despondent Jim plays his record of “Always” on his phonograph — the tune to which he and his beloved Mary danced in the Coney Island dance hall — it leads him and Mary to discover that they live in adjacent flats and provides the clinching irony to this fable about urban alienation.

The same sound version, however, has three brief added dialogue scenes — all of them awkwardly staged and played and unnecessary to the plot; they were clearly tacked on because of the burgeoning commercial fad for talkies.

A silent version (sometimes shown today) of this longer Lonesome highlights the inadequacy of these insertions even further by revealing how totally pointless they are without the actual talk. The oriiginal silent Lonesome, on the other hand, seems entirely adequate. Indeed, it is so grounded in purely (and self-sufficiently) visual forms of rhetoric that it seems unlikely that any filmmaker geared mainly to talkies would have ever conceived it.

A man with a taste for fairy tales who later became an anthropologist, Paul Fejos had an inate grasp of how to articulate the complexity of everyday social experience in a big city. His approach to this is analytical, and his attitude at once progressive and accessible, comic and critical, distanced and affectionate. Working with a popular star of the period in Glenn Tryon, a total unknown in Barbara Kent, and a three-page outline for a story submitted to Fejos at Universal, the talented Hungarian director turned his first big Hollywood feature into a kind of visual fugue in which the separate trajectories of hero and heroine over a single morning compose a poignant harmony of variations and interactions.

In the remarkable opening sequences of the film, the alternation and co-existence of Mary and Jim form the ‘melodic’ basis of Fejos’ rich visual orchestration. The scenes of volatile and impersonal city life that run concurrently as a backdrop to their routines comprise the complementary notation. The film critic Graham Petrie has given a detailed description (in Film Quarterly, Winter 1978-79) of Mary’s and Jim’s parallel working day which conveys a keen sense of this rhythmic duplicating principle:

“In the factory sequence, Fejos employs a barrage of highly sophisticated effects to produce a sense of the stress and monotony of a machine-dominated environment, while, at the same time, he manages the parallel continuity between the events of Jim’s day and those of Mary’s. Within the constant framework of a clock remorselessly ticking away the hours of their incarceration, the camera begins on a shot of Mary at her job of telephone operator, then pans to the left, simultaneously dissolving into a shot of Jim at work that continues to become a long track along the workbenches; the camera then moves back to the right, dissolving in the middle of what appears to be one continuous movement to return to Mary at the switchboard. As Mary answers phone calls, the screen around her begins to fill up with small, superimposed images of faces of men and women talking on the phone, shouting, yelling, complaining, a yammer and babel of voices that steadily rises in intensity; the faces rapidly appear and vanish, piling up on top of each other until, at the climax of this scene, there are at least half a dozen different layers of superimposition together on the screen. From this the camera turns left again, dissolving once more to reveal Jim punching out an endless series of razor blades.”

Ultimately dovetailing his ‘diptych’ principle into first a love story, then the revelation that Mary and Jim live next door to each other, Fejos offers an exemplary case of structure dictating style as well as content. Here (as in Jacques Tati’s 1968 Playtime), the visual patterning of isolated units that collectively comprise city life makes the viewer wiser than any of the characters, yet in no sense superior. And in the overall sweep of this very affecting love story, Fejos is able to involve the viewer closely in the growing personal rapport between Jim and Mary at the same time that he ingeniously integrates them into a more universal context.

JONATHAN ROSENBAUM