This very lengthy essay was assembled in 2013 out of several previous pieces of mine, but I no longer recall the occasion for it. — J.R.

Introduction

One of the problems inherent in using the term “cult” within a contemporary context relating to film, either as a noun or as an adjective, is that it refers to various social structures that no longer exist, at least not in the ways that they once did. When indiscriminate moviegoing (as opposed to going to see particular films) was a routine everyday activity, it was theoretically possible for cults to form around exceptional items — “sleepers,” as they were then called by film exhibitors — that were spontaneously adopted and anointed by audiences rather than generated by advertising. But once advertising started to anticipate and supersede such a selection process, the whole concept of the cult film became dubious at the same time it became more prominent, a marketing term rather than a self-generating social process.

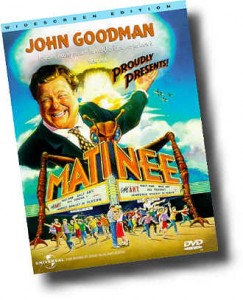

Joe Dante deserves a special place in what I would call the post-cult cinema because he is one of the few commercial American directors I know who has refused to hire a personal publicist, and for tactical reasons — someone, in short, who chooses to be recognized at best only by initiates (that is, by fellow cultists or would-be cultists, his comrades-in-arms) rather than by the public at large. And this is a logical move for a genuine film enthusiast who relishes those branches of genre cinema where anonymity functions as a veritable badge of both authenticity and community. (Indeed, one could argue that even the exploitation “auteurs” such as William Castle — the model for Lawrence Woolsey [John Goodman] in Dante’s masterpiece Matinee (1993) — were recognizable as auteurs during their heyday in the 1950s mostly to horror specialists, not to the more casual moviegoers who could be expected to identify De Mille, Disney, and Hitchcock.) This also becomes an essential tactic for American filmmakers who choose to be political (which invariably requires some form of generic subterfuge) rather than simply to exploit political issues.

Even at his angriest, as in Homecoming (2005), the first Hollywood movie to register the obscenity of the American occupation of Iraq, Dante chooses to emphasize the outrage of the Bush administration’s hypocrisy rather the purity or correctness of his own views. Insofar as he qualifies as a moralist, it’s the morals of spectatorship that ultimately concern him the most—in Explorers and his Twilight Zone episode (both 1985), in The ‘burbs (1989) and Small Soldiers (1998), not to mention The Hole (2009). One might even suggest that his motto harks back to the formulation of William Butler Yeats: “In dreams begin responsibilities.”

Go to the online Trailers from Hell (trailersfromhell.com), where Dante serves as one of eight relatively anonymous team members, and compare his function there to the star persona of an Oliver Stone, brandishing his “leftism” to illustrate, for instance, the alleged Shakespearean dimensions of a Richard M. Nixon. But the world of an Oliver Stone ultimately depends on the metaphysical absolutes of patriarchal heroes and villains, even when they turn out to be the same character — in contrast to the more equitable and liberal values of a Frank Tashlin or a Joe Dante, which usually refuse such complacencies for the sake of cheerful ridicule. The worst and best thing that characters in a Tashlin or a Dante live-action cartoon can be is silly and/or idiotic, and at least part of what makes them silly or idiotic is the assumption of heroism and villainy in others. Consider the governor of Idaho (Beau Bridges) in The Second Civil War (1997), who plays shamelessly to his xenophobic constituency by closing his state borders to a plane full of Pakistani orphans while remaining completely smitten with the ethnicity of his Mexican mistress (Elizabeth Peña); even if the consequences of his demagoguery turn out to be apocalyptic, the film prefers to view him chiefly as a lovable asshole.

Like Tashlin, Dante may ultimately qualify more as a commentator and embroiderer than as a storyteller. Embarking on a spin-off to his biggest hit (the 1984 Gremlins, a horror spoof founded on an all-purpose metaphor), he chose in Gremlins 2: The New Batch (1990) to pile on gags rather than pursue a meaningful plot, adopting more or less the same route he would later take in Looney Tunes: Back in Action (2003) — the route of Tashlin’s Son of Paleface (1952), his locus classicus. This is why even in Innerspace (1987), one of his rare departures from both horror and satire, he can take so much pleasure in his adopted movie tropes — in this case, the sheer delight of crosscutting itself. (This is a romp that postulates the injection of a miniaturized Navy test pilot played by Dennis Quaid into the body of a hypochondriac played by Martin Short, leading to simultaneous and parallel narratives as each character’s progress influences the other’s.)

***

What follows is a consideration of several Dante films, drawn from separate reviews and organized under four separate categories: Gremlins and Teenagers, Parables of Spectatorship, School of Tashlin, and The War Trilogy. My extended consideration of Small Soldiers at the end of this discussion excludes my detailed inventory and analysis of the American reviews this movie originally received, which can be found in my book Movie Wars: How Hollywood and the Media Limit What Films We Can See (2000).

1. Gremlins and Teenagers

Gremlins (1984) — Joe Dante’s biggest hit (1984) to date, having grossed over $200 million worldwide, in which cuddly Spielbergian pets turn into vicious beasties — was also the movie that convinced me I should start paying closer to attention to him and his work. It led my colleague Dave Kehr to conclude, “Dante is perhaps the first filmmaker since Frank Tashlin to base his style on the formal free-for-all of animated cartoons; he is also utterly heartless.”

I agree with Kehr’s first premise but not with his second. Dante’s subversive and occasionally unnerving high jinks with the processes of movie and TV watching, which are for me basic to all of his best work, reveal not only a skepticism toward the media combined with the reflexes of a passionate film buff, a genuinely dialectical relation to spectatorship, but also a profound respect for the viewer — a respect was only amplified later by his splendid war trilogy of Matinee, (1993) The Second Civil War (1997), and Small Soldiers (1998), which for me remains the hub of his major achievement.

But to understand a little better some of what Gremlins is doing, it helps to consider Dante’s relationship to its executive producer, Steven Spielberg. As a producer and director, Spielberg has largely concentrated on two key subjects: power and magic. The power that interests him is, of course, the power that he commands — which he often sees reflected in the power of others (ranging from Oskar Schindler to Abraham Lincoln to both Peter Pan and Captain Hook to Hobby, the putative villain played by William Hurt in A.I. Artificial Intelligence)–and the magic is that of his chosen medium, whether this happens to be in a movie theater or on a TV screen (or on a computer or iphone, for that matter). Combine these with the input of director Joe Dante, another film buff, and you get a movie about movies, triple-distilled. And the curious achievement of Gremlins is that it made such self-absorption commercially viable, at the same time—and perhaps in part because–it refused to conform to any single, sustained social meaning. Much as the depiction of American forces in Vietnam in Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now was designed to placate hawks and doves alike (without, however, addressing the interests of Vietnamese people, either from the North or the South of that country), Gremlins was cleverly contrived to please skeptics as well as believers, optimists as well as pessimists about the American way of life in general and Hollywood in particular. Thanks to a disconnected episodic structure that suggests several separate movies crammed together — a strategy that incidentally re-creates the fragmented, discontinuous flow of TV watching (as well as most other contemporary forms of spectatorship), viewers of Gremlins are essentially invited to chart out their own justifications for enjoying Dante and Spielberg’s treasure trove.

One justification is offered by the movie’s plot, which offers us a cautionary Christmas fable set in a Frank Capra universe. Rand Peltzer (Hoyt Axton), a good-natured and kind-hearted inventor whose inventions seldom work, buys a furry little animal named Mogwai for his son Billy (Zach Galligan) from a Chinatown curio shop. He is warned that three rules of gremlin maintenance must be followed: Keep them out of light, don’t ever get them wet, and, above all, never feed them after midnight. But after Billy inadvertently breaks all three rules, Mogwai replicates into several more gremlins, who evolve into sinister beasts. They multiply further, taking over the town — and Billy must try to stop them. To seal the high moral tone, the wise old Chinese merchant finally emerges to reclaim Mogwai, implying that Westerners lack the maturity to deal with such magical creatures.

So much for the moral, upstanding movie some viewers apparently want, which Gremlins dutifully supplies. But what about the film’s more immoral and irresponsible aspects? Gremlins offers these in such abundance that it conjures up a second movie, diametrically opposed to the first, which delights in assaulting everything the other movie stands for: Christmas, Norman Rockwell’s America, consumer society, family entertainment, and so on. Spielberg’s original idea for Gremlins was that it would be a fairly straight horror film, and Dante’s goofiness edged it more and more into comedy while it was being shot. But to his credit, it was Spielberg who wound up protecting the movie’s most curious and creepy scene from suppression by other executives: the teenage heroine Kate’s deadpan black-comedy monologue about her father being discovered dead in a chimney when she was nine, dressed as Santa Claus and with a broken neck–a monologue that years later became the reference-point for an elaborate gag about Lincoln’s birthday in Gremlins 2.

While the “moral” (and kitschier) side of Gremlins can be taken in two possible ways, as sincere or cynical, the amoral side seems to break up like the gremlins themselves into an infinity of possible meanings. The evil beasties can be plausibly read at various times as (a) adolescents, (b) blacks , (c) Native Americans, (d) good ole boys, (e) people who like Walt Disney (or Steven Spielberg) movies. (f) mischievous kids, (g) hoboes, (h) monsters — anyone can add to the list. And the advantage of this ambiguity is a somewhat troubling and hard-to-define aftertaste that doesn’t quite allow one to come away from the film with a full sense of closure. (Perhaps this bears some relation to the “utter heartlessness” that Kehr had in mind.) Sometimes the most subversive and complex thing one can do in a Hollywood movie is to give audiences exactly what you think they want, never hesitating to pursue the resulting contradictions to the limit. Perhaps no viewer can swallow the concoction whole without incurring a little bit of heartburn, but each is guaranteed to get a little more than he or she bargained on. (On a more modest scale, the same principal can be seen in the best episode of the mostly expendable 1987 sketch revue Amazon Women on the Moon. Dante’s bad-taste rendition of movie critics reviewing a failed life — a sequence that eventually turns into a celebrity roast for the dead person, attended by Slappy White, Jackie Vernon, Henny Youngman, Charlie Callas, and Steve Allen – is much too sinister for comfortable laughs, but queasy in the best Dante manner.)

Because Dante concentrates so much on individual shots and ideas and so little on overriding concepts, Gremlins, like many of his other movies, seems ideally suited for home video. As an inspired (if unruly) collection of bits, it virtually cries out for the pause button — not to mention forward and backward searches. Film freaks can freeze-frame in order to pinpoint the multiple movie references. Splatter hounds can leapfrog from one flamboyant, grisly death to the next. And special-effects aficionados can linger on the loving gremlin crowd scenes, in a tavern, movie theater, and elsewhere. All of which add up to an aspect of his talent that is more related to spectacle than to narrative.

Seeking to avoid camp, the Rebel Highway movies, all remakes of American International Pictures quickies from the 1950s, aspire to a kind of historical revisionism, with fascinating if uneven results. On a conventional level the best of the four I’ve seen is Dante’s Runaway Daughters, the only one that plausibly captures the period in which it’s set — 1957, shortly after Sputnik went into orbit and the year after the original Runaway Daughters was made. Scripted by Dante’s usual writer, Charles Haas, the movie careens from an opening newsreel montage of 50s events to a double-date make-out session at a drive-in showing I Was a Teenage Werewolf. Eventually it focuses on three teenage girls who decide to run away after one of them becomes pregnant and her boyfriend takes off to join the Navy. (Sputnik figures significantly in both his seduction patter and his excuse for enlisting, and Corman and his wife put in cameos as his parents.) Hoping to intercept him in San Diego before he’s shipped off, the girls fake a kidnapping note, steal a car, and scratch off, heading south. Reportedly sticking closer to his source than most of the other series directors, Dante gives his material charm, wit, and verve by working gracefully with his likable cast (including such familiar faces as Joe Flaherty, Robert Picardo, Fabian, John Astin, and even Cathy Moriarty in an uncredited cameo). He seems wholly at ease with both the period and the AIP mode, both of which he affectionately parodies.

A typical spin on the material comes when AIP (and Dante) regular Dick Miller, playing a private detective investigating the girls’ disappearance, lectures four of their parents: “Do you people ever sit down and talk to your kids? I mean really talk to them about sex and sexual diseases, about peculiar practices? About the strange night world of twisted kicks [an electronic instrument starts to warble on the sound track, evoking 50s SF movies], of weird rituals and equipment? Of whips and chains and rubber balls and dildos and handcuffs?” A little later, gazing at the poster for the original Runaway Daughters at a drive-in, Miller sighs, “Ah, they don’t make ’em like they used to” — Dante’s sentiments exactly. Perhaps one reason they don’t is a certain lost innocence; Dante seems to betray his own lost innocence just after the runaway girls discover that a couple of hunters wrongly suspected as kidnappers and shot by the cops were actually “mad-dog killers,” not innocent bystanders. Instantly the girls’ misery turns to joy, and their implied indifference to the deaths of the hunters and their victims as soon as their own responsibility is lifted sadly registers more as a 90s response than a 50s one.

2: Parables of Spectatorship

A knowledgeable connoisseur of the American cartoon, Dante makes movies that take place in the kind of manic world where anything can happen. This sensibility bore particular fruit in his segment of Twilight Zone: The Movie (set in a universe ruled by the mind of a vindictive little boy who loved cartoons) and the climactic sequence of his Explorers (a nightmarish Mixmaster version of American TV strained through the sensibility, body, and technology of an extraterrestrial mimic); both of these segments anticipated the subversive universe that other filmmakers would develop later on Pee-wee’s Playhouse. In ideological and aesthetic terms, this translates into the aforementioned ability to make different movies for different audiences at the same time. Expedient rather than cynical, Dante nearly always contrives to give his audience at least two movies to choose from: in Gremlins one can enter either the idealized Capra universe or the irresponsible realm of the monsters who seek to undermine it; in Innerspace one can identify with the adventures and attitudes of either the pilot or the neurotic.

In the case of The ‘Burbs, the moral choices available to the viewer are even broader. The movie can be read as a satire about suburban conformists and snoops — xenophobic busybodies who can’t tolerate the presence of any sort of eccentricity in their midst. Or the movie is a cautionary tale about the dangers of insulation and ignorance — minding one’s own business and being unaware of the horrible things that are happening right next door. Or, finally, one can take the noncommittal stance assumed by the teenage characters in the movie, who are as undisturbed about the mysterious neighbors as they are amused by the xenophobic snoops trying to uncover them; the kids are simply around to enjoy the show.

By building all three seemingly contradictory attitudes into this movie, Dante and screenwriter Dana Olsen don’t abdicate their moral responsibility. It might be more accurate to say that they honor the pluralistic and democratic possibilities of their story, and do so in such a way that the viewer doesn’t have to adopt any one of these three attitudes exclusively. The ‘Burbs, which has no pretensions at all about “making a statement” or addressing a social issue, implicitly respects an audience’s ability to consider events rather than merely react to them, and to do so from more than a single perspective.

The plot couldn’t be simpler, and if Dante is grand enough to begin and end his movie with a shot of the spinning globe, he takes care to remind us that it’s nothing more than the Universal Pictures logo. In a suburban neighborhood — actually Colonial Street in the Universal Studios back lot, where Leave It to Beaver among other TV shows was set — Ray Peterson (Tom Hanks) is spending his vacation at home, but his peace is disturbed by the presence of a strange new family on the block, the Klopeks. His paranoid neighbor Art (the John Candy part played by Rick Ducommun) informs him that the family’s previous house burned to the ground, and that the three members of the all-male family never seem to go out except at night.

The disappearance of another neighbor starts to get Ray and Art even more hot and bothered, and they’re joined in their suspicions by Mark (Bruce Dern), a cantankerous Vietnam vet who’s even more intolerant of the Klopeks’ weirdness. At night, they witness all kinds of strange goings-on at the dilapidated Klopek house: a lightning rod on the roof causes the basement to blaze with fiery light (shades of Frankenstein), and the youngest member of the household, Hans (Courtney Gains), removes a suspicious-looking garbage bag from the trunk of his car.

Ray also learns from his son, Dave, that the Klopeks have been digging holes in their backyard at night, and a neighborhood dog retrieves a human thighbone — from the same yard. But as the plot thickens and the mystery deepens, it becomes increasingly clear that Ray, Mark, and Art are the only ones who are worried about the Klopeks, or at least worried enough to start snooping in earnest. Ordinarily one would expect the local kids to become the amateur sleuths in this sort of plot, but Ray’s son, while observant, is basically unconcerned, and Ray’s wife, Carol (Carrie Fisher), and Mark’s wife, Bonnie (Wendy Schaal), only become involved in order to placate their husbands. Ricky (Corey Feldman), the local teenager, is interested only as a passive, amused spectator. He treats the activities of his older neighbors — Klopeks and straight men alike — like a drive-in movie, going so far as to set up chairs on his porch facing the action.

Part of Dante’s wit and talent in handling this bunch of characters is to view them all from an affectionate but critical distance. Mark and Art are depicted mainly as bumbling fools, and while Tom Hanks’s Ray seems a little less silly than his fellow sleuths, the movie never asks us categorically to share his viewpoint either. When we finally get to see more of the Klopeks — Uncle Reuben (Brother Theodore) and Dr. Werner Klopek (Henry Gibson) — they basically come across as stock Old Dark House residents with a few Nazi mad-scientist trimmings. But the movie isn’t so much concerned with proving that Ray and his cohorts are either right or wrong about their suspicions (although it proves incidentally that they’re right as well as wrong) as it is in showing the comic interactions between all the people in the neighborhood. Several points of entry are offered to the audience in assessing this very anti-Spielbergian suburban hell, and all of them are equally funny.

The ‘Burbs is a small and modest entertainment rather than a broadside, so one doesn’t want to make too much of its clever strategies, which convert its three adult heroes into children, their wives into mothers, and the neighborhood kids into relatively mature grown-ups. Some of the pleasures to be found in the margins of this romp are the inside references that tend to be a Dante specialty, ranging from a box of Gremlins breakfast cereal to the name of the author of a dusty volume called The Theory and Practice of Demonology (one Dr. Julian Karswell, a character played by Niall MacGinnis in Jacques Tourneur’s classic Curse of the Demon).

3: School of Tashlin

Gremlins 2 The New Batch (1990) is a good deal simpler than Gremlins. This time, it might be said that the gremlins are simply us — nasty little consumers who are just a bit more obvious about their predilections and temperaments than we are. Indeed, one of them, after drinking a “brain hormone” in a mad scientist’s laboratory — a site for genetic research called Splice o’ Life–becomes downright articulate and urbane (with a voice supplied by Tony Randall), and when asked just what it is the gremlins want, he coolly replies, “Civilization: chamber music, the Geneva convention, Susan Sontag.”

Billy’s inventor father is mentioned once, but he never reappears; both his narrative function and his malfunctioning gadgets are taken over by Daniel Clamp (John Glover), a Manhattan development tycoon based on Donald Trump and Ted Turner, whom Billy and his girlfriend Kate (Phoebe Cates) both work for. The “fully automated” Clamp Centre with its omnipresent surveillance and PA systems, where practically the entire movie is set, is already a dysfunctional totalitarian monstrosity long before the gremlins get loose in it, and this time there’s no indication that the world disrupted by the gremlins is even remotely worth saving. Clamp himself is too silly and innocent to register as a proper villain — a designation assigned only in passing to a company hatchet man (Robert Picardo) and, to a lesser extent, to an ambitious chain-smoking supervisor (Haviland Morris) trying to lure Billy away from Kate.

Unlike its predecessor, Gremlins 2 has no ambiguous attitudes about its world and its characters, or any subversive agenda apart from its up-front satire. What you see and hear is what you get; it’s often funny but never very profound. The movie invites you to get lost in its amusing details, but it lacks both the suspense and the occasional scariness of the original.

“[My films] aren’t mainstream movies and I’m not a mainstream director,” says Joe Dante in the July issue of Cinefantastique magazine.

“Long, isn’t it?” remarks Daffy Duck while the end credits of Gremlins 2 are rolling; then, somewhat later, “Patently ridiculous”; and finally, “Still lurking about? Don’t you people have homes?”

One might argue that Dante and Daffy are making the same basic point. Both times I saw Gremlins 2 — first at a crowded press show, then at a sparse weekday matinee — the message came through loud and clear. At the press show, by the time Daffy started joshing those of us who were still hanging around — unwilling to let go of a movie that had afforded us so much pleasure, and also pretty sure that Dante, our soulmate, would reward us for staying (as indeed he did) — the more mainstream reviewers in our midst, those fellows who are generally the last to arrive and the first to leave, had long since departed.

Quite literally, Daffy and Dante weren’t speaking to these guys at all. And when it came to the weekday matinee, all the mothers and baby-sitters had bustled off their kids long before the first of Daffy’s interjections; by the time of the last wisecrack, I was the only one left, apart from a few ushers who were cleaning up.

Perhaps I’m exaggerating the difference; after all, the original Gremlins, which was pretty democratic as well, and almost as easygoing, grossed over $200 million worldwide, and it lacked both stars and very much narrative. But one of the main ideas of the sequel is how much things have changed in only six years — even more than the move from small-town America to Manhattan implies. Mr. Wing, whose curio shop is the only obstacle to a Clamp development project, dies during an ellipsis in the opening reel, and the only elder statesman who comes anywhere near replacing him is, significantly, a disgruntled TV actor–Grandpa Fred (Robert Prosky), an old-time vaudevillian who introduces horror movies on TV in a cape and heavy makeup. (He’s the one who winds up an impromptu talk-show host, interviewing the brainy gremlin on Clamp’s own cable channel.)

Perhaps the biggest single difference between Gremlins 2 and its predecessor is the degree of urgency and discovery in each picture. Gremlins taking over a fancy New York skyscraper is more of a premise than a plot, and the characters don’t exist independently of this premise.

Nearly all the dark elements in the original are kept firmly under wraps. Nobody dies this time except for the mad scientist–an updated Dr. Moreau type called Dr. Catheter (Christopher Lee), who is more a juicy movie icon than a character in his own right. There’s also much less cruelty here, nothing like the stingy old lady in Gremlins–fashioned after Lionel Barrymore’s Mr. Potter in It’s a Wonderful Life and Margaret Hamilton’s Wicked Witch in The Wizard of Oz–who fantasizes about torturing Billy’s beloved dog, or the gremlins’ hanging the same dog from the porch ceiling with a string of Christmas-tree lights.

Ever since Gremlins, Dante has seemed the most intelligent and progressive of the postmodernist Hollywood directors to have evolved under Spielberg’s sponsorship, a group that includes, among others, Tobe Hooper, animator Dob Bluth, and Robert Zemeckis. (I should point out that “Dante” should be read here as auteurist shorthand for Dante and his production team–which includes such regulars as producer Michael Finnell, cinematographer John Hora, and production designer James Spencer, as well as screenwriter Charlie Haas and coproducer Rick Baker, who supervised the special effects.) Despite his compulsive citations of other movies, Dante can’t be written off as a copycat. He always applies his encyclopedic knowledge of movies with critical discernment and imagination, and he’s plainly having a field day in Gremlins 2.

Conceptually speaking, however, his new film is less fresh and audacious than his episode for Twilight Zone–The Movie or his features Innerspace and The ‘Burbs, and even its best moments never match the queasiness of the climactic sequence in Explorers. The reasons for this seem to be twofold. The special-effects work, while excellent, is so extensive that it tends to swamp any conceptual basis behind it–a problem that to my mind also works against certain portions of Hitchcock’s The Birds (which Dante seems to be using here as a frequent reference point). And the fact that Dante made this movie in the first place appears to be the consequence more of the studio’s desperation to develop a sequel than of any driving inspiration on his part.

Looney Tunes: Back in Action

It’s remarkable that Dante, one of the most personal directors working in Hollywood, has never had or sought to have a possessive auteur credit on his pictures. He says he finds it easier to do what he wants without this sort of claim or exposure. For the same reason he, unlike most of his colleagues, has never hired a personal publicist. The idea of a “Joe Dante movie” or a “movie by Joe Dante” is mainly a presumption of his fans, myself included, rather than a product sold by his employers. It’s worth observing that this modesty is also honest: he, like most of the directors who use the credit “a film by,” doesn’t control the final cut of a movie.

I don’t know who controlled the final cut on Looney Tunes: Back in Action — which seems even more personal than Small Soldiers — and the screen credits don’t tell us much. Dante also avoids taking any writing credit on his movies. According to a New York Times story by David Edelstein, the only credited writer on this movie, Larry Doyle, “pulled out of [the film] in February after vehement disagreements over animation, character voicing and jokes,” and 28 other writers, none of them credited, “were involved in varying capacities.” So it’s hard to say who deserves credit for authoring Looney Tunes, especially when one considers that the cartoon characters that dominate the action come mainly from the work of Tex Avery, Robert Clampett, Friz Freleng, Chuck Jones, and Frank Tashlin — all dead and uncredited. And one has to be careful not to limit the cast list to the on-screen actors, because one actor, Joe Alaskey, furnished the voices of the two leads, Bugs Bunny and Daffy Duck, and those of three secondary characters, Beaky Buzzard, Mama Bear, and Sylvester. In any case, Dante’s stamp is evident on almost every frame, in part because he’s not simply a creator but a creative filter, assiduously minimizing all elements that aren’t Dante-esque.

What does his stamp consist of? For one thing, a faithful reliance on a stable of secondary actors, the most prominent of whom include Dick Miller (as a security guard), Roger Corman (as a Warners director), and Kevin McCarthy (returning briefly as the hero of the original Invasion of the Body Snatchers) — all of them associated with Dante’s experience as a movie fan in the 50s and 60s and an employee of Corman’s in the 70s. For another thing, there’s a reliance on horror and SF movies of the 50s and early 60s — from The Man From Planet X and This Island Earth to Forbidden Planet and Psycho — as well as Warners cartoons dating back to the 30s, all supplemented by other pop-movie references. (From 1968 to ’73 Dante worked as a film reviewer for a trade magazine, and many of those reviews are being reprinted in the magazine Video Watchdog.) Finally there’s an affection for both monsters and cartoon characters and a cheerful contempt for powerful institutions and what they commonly represent — a position that becomes full of contradictions once it’s directed at such powerful institutions as Warner Brothers and Acme, the generic manufacturer of products ordered by Wile E. Coyote in Road Runner cartoons. These two multinational entities are mocked more than others in Looney Tunes; a Wal-Mart that appears in the Nevada desert gets only a cameo: “Is it a mirage or just more product placement?” asks Bugs.

The putative human heroes in any Dante work tend to be bland and dumb, while the putative human villains tend to be regarded with amusement rather than rancor. The main human heroes in Looney Tunes are Brendan Fraser, playing an aspiring stunt man for Brendan Fraser, and Jenna Elfman, playing a Warners executive. The main villain is Steve Martin, playing Mr. Chairman, the mad, scheming head of Acme. It’s no surprise that the Warner brothers — much closer to bluenose villains than good guys — are played by Dante semiregulars (identical twins Don and Dan Stanton) and are much less lively than Mr. Chairman. It might seem curious that the Warners company employs Bugs Bunny and Daffy Duck (along with Fraser and Elfman), while the Acme company employs Wile E. Coyote (along with the Tasmanian Devil, Ron Perlman, and Dante regular Mary Woronov); but these two institutions, unlike their employees, are offered as parallel monolithic and monopolistic enterprises rather than as competitors. The ultimate aim of Acme, we discover, is to turn everyone on earth, except Mr. Chairman, into monkeys that can provide cheap labor to churn out products, then back into humans who can buy these products. The ultimate aim of the Warner brothers is to turn everyone except them into monkeys that churn out Looney Tunes: Back in Action, then back to humans who can buy tickets and ancillary products. That Fraser, whose character works for Warners, also supplies the voices of the Tasmanian Devil and She-Devil, who both work for Acme, only underlines this moral equivalence.

According to Jerry Beck and Will Friedwald’s 1989 reference book Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies: A Complete Illustrated Guide to the Warner Bros. Cartoons, Bugs Bunny has appeared in more than 160 cartoons, not counting a dozen “cameo” appearances, and Daffy Duck has appeared in more than 130. Most of the time they appear separately; the most memorable of their joint appearances are probably in three Chuck Jones cartoons — Rabbit Fire (1951), Rabbit Seasoning (1952), and Duck! Rabbit! Duck! (1954). In these films, critic Richard Thompson has pointed out, “the continuing gag has Bugs trying to convince Elmer [Fudd] that it’s duck season, and Daffy telling him it’s rabbit season” — the opening gag of Looney Tunes.

Thompson goes on to argue that these cartoons refined the traits of both characters as they were played off each other, so that Bugs (an unflappable winner modeled on the prototype of Groucho Marx) is partially defined by Daffy (a highly flappable loser who is himself a prototype) and vice versa. Thompson doesn’t say anything about the class orientations of these characters, but I think one could argue that cool Bugs is more upscale, as demonstrated by the comforts of his well-furnished rabbit hole, while the hysterical Daffy often has no pond or other habitat to call his own and usually is treated as a second-class citizen.

This hierarchical distinction seems to be the basis for pairing the two as a competitive comedy team in Dante’s feature, in which Abbott and Costello, Crosby and Hope, and Martin and Lewis also provide models for their relationship. Bugs is the star of their shared cartoons; Daffy protests his second-fiddle status at a Warners executive meeting and gets thrown off the lot. Executive Kate Houghton (Elfman) does the official firing, and DJ Drake (Fraser), a security guard, is given the job of ejecting Daffy. When Daffy protests indignantly, “This is Daffy Duck,” Kate replies, “Not anymore — we own the name.” In the process of removing Daffy, DJ gets fired too. DJ and Kate eventually become a standard-issue romantic couple, which might seem unlikely given their apparent class difference; but we quickly learn that DJ is actually the son of Warners’ biggest live-action star, Damien Drake (Timothy Dalton), so the apparent difference is deceptive. Daffy’s inferior status relative to Bugs is ultimately made to seem equally deceptive — particularly when DJ is paired with Daffy (as if to further justify his surname) and Kate (whose surname is derived from Katharine Hepburn’s middle name) is paired with Bugs as they drive off in separate cars for Las Vegas. All four characters prove to be Hollywood to the core.

It’s characteristic of Dante to be brazenly yet offhandedly honest rather than cynical about these discrepancies. What makes him unusual as a satirist is that he’s an equal-opportunity ridiculer, showing just as much affection for Beau Bridges, the putative villain of his 1997 TV movie The Second Civil War, as for any of the more sensible characters. Though he clearly cares more for the cartoon characters here than for any of the live-action ones, he gamely allows Steve Martin to try to compete with them by mugging his head off — though of course the poker-faced reaction shots of Bugs and Wile E. Coyote always elicit more laughs. Indeed, viewers are likely to come away from Looney Tunes concluding that the cartoon characters are far more real, substantial, and sympathetic than any of the humans–not my conclusion after watching Robert Zemeckis’s much slicker Who Framed Roger Rabbit. This superiority is less peculiar than it sounds: after all, many more human hours — adding up to decades rather than weeks — have been invested in the creation, elaboration, and perpetuation of the cartoon figures. As collective creations, they make me think of Chartres — which paradoxically makes Dante’s appreciation of them singular and not at all collective.

My only regret about the screen space accorded these favorites is that some of them don’t get more. Porky Pig and Speedy Gonzales turn up at the Warners commissary just long enough to explain how political correctness has ejected them from the movie, blustery Foghorn Leghorn gets shoehorned into cameo slots as a nightclub emcee and casino dealer, and volatile Yosemite Sam gets turned into a secondary villain. (Heather Locklear as Dusty Tails, a live-action showgirl-spy, gets upstaged by the cartoon cameos, but who cares?)

Apart from Hollywood and Las Vegas, the main settings of this romp are the Nevada desert, a secret government laboratory (“Keeping things from the American public since 1947”) presided over by Joan Cusack, Paris, the wilds of Africa, and outer space — though as critic David Ehrenstein has suggested, it might be argued that the characters never really leave Las Vegas, since all the other locations essentially look like Vegas theme-park hotels. In Paris, for instance, the Louvre — where Bugs, Daffy, and Elmer Fudd go on a wild chase through famous paintings by Dali, Munch, Seurat, and Toulouse-Lautrec — is right across from the Eiffel Tower. We also get glimpses of posters for two lesser-known Jerry Lewis movies, and one of them, Which Way to the Front?, is given a fake pidgin-French title rather than the correct French title, Ya, ya, mon géneral. (For my money, a more apt Lewis tribute is Perlman’s brief impersonation of The Nutty Professor‘s Julius Kelp before and after he’s turned into a skeleton.) And on a remote mountain peak in Africa is a sign reading “Lifeguard off duty, no swimming” that seems straight out of a Bill Elder panel in a 50s Mad comic book. In any case the film’s universe and its logic belong to the animated characters more than the live-action ones: the Acme headquarters, which starts out as a surveillance satellite hovering over the Nevada desert, becomes the top floor of a city skyscraper at the end of the same sequence.

The film on which Dante had the most freedom and control, to the best of my knowledge — Gremlins 2: The New Batch — is set inside another skyscraper. This 1990 gag fest is a pleasurable, footloose ramble, but it lacks the satiric bite of his so-called war trilogy — Matinee (1993), The Second Civil War, and Small Soldiers — which I regard as the peak of his work to date. As a comedy, Looney Tunes is closest to Gremlins 2, though I doubt Dante was given such a free hand with it. And it’s hard to tell whether it will have as much meaning for kids who don’t catch the film references and don’t know or care who Dante is; its life in the marketplace probably depends more on its status as an anonymous factory product than its charm as a nostalgic personal manifesto. (This was also true of Small Soldiers, though that movie generally scored better with kids than with the uptight adults whose taste for war it ridiculed — which is probably why it did better on video than in theaters.)

In a related way, the difference I see today between two Bob Hope comedies littered with in-jokes — Frank Tashlin’s Son of Paleface in 1952 and Hal Walker’s Road to Bali of the same year — is probably less apparent to people simply looking for laughs than it is to auteurists like me. I loved both movies as a kid, but today the Tashlin looks snappy and sweet, while the Walker looks tired and sour. That’s partly a consequence of how Tashlin and Walker made their films, and partly the result of my reading their films differently today. But I won’t have to wait another 50 years to see that Looney Tunes is lovable and Who Framed Roger Rabbit is only likable. Robert Zemeckis isn’t a Hal Walker, but Joe Dante’s right up there with Tashlin, Avery, and Jones.

4: The War Trilogy

Oriental incense to get the audiences in the mood. The stage manager agreed to try another of my ideas — Count Dracula would vanish on stage in a cloud of smoke, then suddenly reappear in the audience. Snarling at the frightened spectators, he would again vanish and appear back on stage. I began to learn firsthand the value of good publicity and showmanship.

Adolf Hitler was unwittingly to teach me the lesson again nine years later. Hitler was indirectly responsible for opening the doors of Hollywood for me. — William Castle, Step Right Up! I’m Gonna Scare the Pants Off America: Memoirs of a B-Movie Mogul

It’s not the Russians — it’s Rumble-Rama. — Lawrence Woolsey (John Goodman) in Matinee

As luck would have it, I saw Joe Dante’s ferocious and lighthearted new about John F. Kennedy “standing up to” Nikita Khrushchev while the world held its breath — barely an hour after reading in the paper that the world was holding its breath to see if Bill Clinton, in his first days of office, would “stand up to” Saddam Hussein. Despite the intriguing coincidence I doubt that many of my colleagues would jump to the conclusion that Dante made a movie with anything at all to say about the way we live and think today. After all, Matinee is set during the Cuban missile crisis — it’s about war fever in 1962.

A horror-movie schlockmeister is the central character in Matinee — a jovial showman named Lawrence Woolsey (John Goodman) who’s clearly modeled on William Castle, master of the horror-exploitation gimmick (and underrated director of some earlier noirish B-films like When Strangers Marry and The Whistler). Woolsey’s relation to the Cuban missile crisis is clarified when he takes on the role of surrogate father to 15-year-old Gene Loomis (Simon Fenton), who has recently moved to Key West with his family. Gene’s father, who’s in the Navy, has been “sent out” to parts unknown on the day the story opens, shortly before a special bulletin interrupts Art Linkletter’s TV show People Are Funny to bring on President Kennedy demanding the withdrawal of offensive missile sites recently spotted in Cuba.

In fact, Gene’s father never puts in a single appearance in Matinee — unless one counts some brief glimpses of him in a home movie his wife (Lucinda Jenney) tearfully watches — so one might say that, mythically and emotionally, Kennedy in his sole TV appearance is the father’s replacement. But Woolsey — “America’s number-one frightmaster,” as he calls himself — is present in the opening scene, in a trailer for his latest horror production, which Gene watches; shortly thereafter we learn that Woolsey will be appearing in person at the theater, on Saturday, to present a special matinee preview of his film. In fact, as soon as Woolsey appears in the flesh, not long after Kennedy’s speech, he becomes the movie’s most important patriarch, supplanting Kennedy, Adlai Stevenson (who appears briefly at UN hearings on TV), and Gene’s missing father — a more ideal version of all of them.

Soon after Woolsey arrives for his show — which involves an elaborate setup with buzzers under the seats and apparitions in the aisles, neatly summarizing some of Castle’s most celebrated gimmicks — the panicky theater manager (Robert Picardo) objects that the country is “on red alert.” “Exactly,” says Woolsey. “What better time to open a horror movie?” And as we discover, Woolsey’s arsenal of scare tactics is every bit as effective as Kennedy’s. Just as the fear of nuclear holocaust creates a hoarding panic among shoppers at the supermarket, Woolsey’s own show reduces his audience to hysterical popcorn fights even before the movie starts. Similarly, the two scaremasters prove equally successful at inspiring hasty retreats; shortly after Woolsey averts disaster by conjuring up a fake nuclear holocaust to drive the audience out of the theater, it’s reported in the news that the implied threat of nuclear holocaust has attained comparable results with the Soviets: Khrushchev has promised that the missiles in Cuba will be dismantled.

I don’t mean to imply, however, that Matinee is didactic, devoted to simple one-to-one correspondences, preachy meanings, or pretentious undertones. And for those who might object to my claims about the movie’s contemporary relevance — those who consider the Cuban missile crisis “serious” and the war drums being beaten in Saddam Hussein’s ears not, as well as those who think the reverse — my point is merely that the movie traces the kind of unthinking giddiness and/or blood lust that fear produces in an anxious audience. Whether the sources of anxiety are Castle’s Homicidal and Nikita Khrushchev or The Silence of the Lambs and Saddam Hussein, our taste for horror-movie monsters who provoke bloody reprisals has persisted for most of this century — a taste that becomes especially pronounced whenever our trigger fingers get itchy. (Less persistent are our memory and awareness of the human cost of scratching those itches — most recently, even currently, our slaughter of innocent ethnics unlucky enough to live under the thumb of Saddam Hussein and therefore ideally suited as cannon fodder, for our grand humanitarian schemes as well as his.)

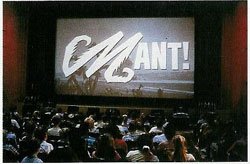

The glory of Dante’s comedy in this movie and others — as aided and abetted by his usual production team, producer Michael Finnell, cinematographer John Hora, and screenwriter Charlie Haas — is that it suggests poetic parallels without insisting on them. Just as a backstage bomb shelter — a chamber in which Gene and his radical girlfriend (Lisa Jakub) become briefly and romantically trapped — bears an interesting resemblance to a bank vault, the kind of war fever Matinee examines has more than one point of contact with the emotions elicited by bad low-budget horror films: Matinee satirically cross-references early-60s fears of nuclear holocaust with Woolsey’s ludicrous new picture, Mant, about a man transformed by radiation into a giant ant. (“Young lady,” one character intones, “human-insect mutation is far from an exact science.”)

Inhabiting a corner of junk heaven in all his pictures, Dante clearly regards each project as a fresh opportunity to show off his appreciation of pop culture. And his pleasure in using familiar bit players such as Jesse White (here the owner of a theater chain) and Dick Miller and John Sayles (members of Citizens for Decent Entertainment) is palpable. As a TV illiterate, I can’t comment on the way TV shows past and present have affected casting decisions and the dialogue, though when it comes to movies Dante has obviously taken full advantage of his resources. It doesn’t seem accidental, for instance, that Cathy Moriarty — Woolsey’s somewhat resigned girlfriend, leading lady, and all-around assistant — reminds us through her accent of her debut role in Raging Bull.

We glimpse a profusion of 1962 “one-sheet” movie posters in the lobby of the film’s theater, the Key West Strand — a pantheon including The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, Hatari!, What Ever Happened to Baby Jane?, Lonely Are the Brave, and Confessions of an Opium Eater. It seems Dante is ticking off his favorites, even if this means working in many more posters than one could imagine such a theater displaying at once. He’s also created many “excerpts” from movies showing in the theater — including a Mant trailer, Mant itself (both in black and white), and something called The Shookup Shopping Cart, a color feature that suggests both Frank Tashlin and live-action Disney. At the same time that Dante has a field day brutally satirizing our desire to scare ourselves and others, he also re-creates early-60s clichés with a relish and a feeling for detail that come very close to love.

As noted above, The Second Civil War (1997), a skillful made-for-cable satire, qualifies as the middle feature in Dante’s his so-called war trilogy, preceded by Matinee (1993) and followed by Small Soldiers (1998). Viewers who consider it the best of the threesome may have a point, though its lack of a theatrical run in this U.S. makes it better known overseas. Beau Bridges plays the governor of Idaho who decides to close his state borders to a plane full of Pakistani orphans fleeing a nuclear disaster, and the action is crosscut with national government deliberations (James Coburn as a Presidential advisor) and various kinds of frantic media spin (Dan Hedaya as a network news director). Barry Levinson set this project in motion, so the parallels with Wag the Dog aren’t accidental, but one of the essential ingredients brought to it by Dante, the least Swiftian of satirists, is that nobody’s a villain, even when behaving like an idiot and/or a hypocrite.

During the spring of 1998, not long before the American release of Small Soldiers, I happened upon “The Toys of Peace,” a wise and wicked tale by Saki included in A. S. Byatt’s recent collection, The Oxford Book of English Short Stories. Set in 1914, it recounts the noble and doomed efforts of the hero to interest his two nephews, aged nine and ten, in “peace toys”: models of a municipal dustbin and the Manchester branch of the YWCA, lead figurines of John Stuart Mill, Robert Raikes (the founder of Sunday schools), a sanitary inspector, and a district councillor. Forty minutes later, he looks in on the boys and finds that they’ve converted these objects into war toys: the municipal dustbin punctured with holes to accommodate the muzzles of imaginary cannons, Mill dipped in red ink to approximate an eighteenth-century French colonel, with a grisly game plan mapped out to yield a maximum amount of bloodshed, including the remainder of the red ink splashed against the side of the YWCA building.

A mordant rejoinder to PC child rearing in 1914 England, Saki’s story testifies to the long-standing lure of make-believe war to boys. Even more wicked and wise in some ways, Small Soldiers is a trenchant satire rude enough to suggest that some of the make-believe wars boys like to play turn out to be the real ones, including those in Vietnam and the Persian Gulf. The sentiments and fabrications underlying such escapades, as this movie sees it, are not so different from those underlying the games little boys play. This is especially true for civilian spectators who watch the battles from afar, accepting the mise en scène of newscasters and governments the same way that kids accept the game plans of toy manufacturers. But it also applies to some of the participants — the eager enlistees programmed by movies to see warfare as a glorified form of kicking butt. Garry Wills’s recent book, John Wayne’s America, hypothesizes that it was our fantasies about a movie star that got us into Vietnam in the first place. And couldn’t one argue that the two most successful American exports, movies and weapons, are both aggressive, fantasy-driven toys?

Small Soldiers opened in the United States in early July 1998, only two weeks prior to the release of Saving Private Ryan—a feature from the same Hollywood studio, DreamWorks, and directed by the man, Steven Spielberg, who effectively produced Small Soldiers—adding pertinence to the satire for anyone who cared to connect it with contemporary reality. To my way of thinking, Spielberg’s film represented a sophisticated form of warmongering, motored by clever, mainstream adaptations of practically every war film he’d ever seen; yet although his own discourse was every bit as cross-referenced to other war films as Dante’s, this fact seemed far from apparent to the American press, which applauded Spielberg’s film precisely for its freshness and originality. Spielberg drew on second-degree memories of All Quiet on the Western Front, Fuller’s war films, Kubrick’s war films, The Bridge on the River Kwai, third-degree memories of John Ford’s war films, and many others—complete with little kernels of wisdom culled from each of these sources — while Small Soldiers parodied The Dirty Dozen and Apocalypse Now, among others. But the same critical establishment that deemed Small Soldiers both old hat and commercially crass, a remake of either Gremlins or Toy Story (or, in some cases, improbably both) motivated by simple greed, declared Saving Private Ryan to be brand-new and morally enlightening. The impact of the extreme violence of the Normandy Beach landing near the beginning silenced criticism in the same way that shouting can sometimes win an argument.

In short, the media profiles accorded these two releases were so radically different that the relevance of Dante’s film to Spielberg’s went virtually unnoticed. As far as most of the public was concerned, Small Soldiers was anything but an auteur film: the name “Joe Dante,” barely known in the first place among American filmgoers, was given so little emphasis in the film’s advance publicity that I failed to notice it myself and came very close to missing the Chicago press screening. One way of partially accounting for this confusion was the deceptive nature of the ads — which I was later surprised to discover Dante had approved, perhaps as one way of negotiating and rationalizing his ambiguous alliance with the movie’s intricate tie-ins with Burger King and the sale of various war toys. These ads foregrounded the toy soldiers known as the Commando Elite as if they were the movie’s unironic heroes rather than its pathetically programmed comic villains, falsely equating the movie’s essence with the crassness of Commando Elite’s manufacturer in the movie, known as Globotech. Until I noted in the ads’ fine print that Dante was the director, I came close to skipping the film myself thanks to this cheesy promo.

But don’t we all tend to lay critical grids over most films before we see them? A year or so ago I discovered in The Realist, Paul Krassner’s humor magazine, that the Chinese title of Oliver Stone’s Nixon was The Big Liar — which led me to speculate that if Stone had had the balls to give his movie that title in English, I probably would have hated it less. (I also have to admit that the aura of hushed respect surrounding Saving Private Ryan already made me approach it with some suspicion; for that matter, I’m wary of trusting the rhetoric of any director who chooses to begin and end a picture with the waving of an American flag — even a somewhat grey and tarnished American flag, as in this case, still sounds a note of sanctity.)

Perceived almost exclusively as a summer release for small children with multiple commercial tie-ins, Small Soldiers was for the most part reviewed as such, and even though the two multiplex audiences I saw it with in Chicago — as well as the thousands of spectators at the outdoor piazza screening of the Locarno International Film Festival on August 7, 1998, a month after its U.S. opening, where it showed on a double bill with There’s Something About Mary—appeared to fully understand and appreciate it as a satire, the same appreciation in the U.S. media was at best scattered, perhaps because the ads spoke louder than the movie itself. (This is often the case with high-profile studio releases. Austin Powers: The Spy Who Shagged Me, which had a production budget of $35 million, was said to have an advertising budget of between $35 and $40 million.)

By contrast, the same media perceived Saving Private Ryan almost immediately as a serious art film; like Schindler’s List and Amistad (and, much later, Lincoln) it was earmarked, long before any reviewers saw it, as a prestige item, a highly personal project, and consequently a brave commercial risk on the part of both Spielberg and DreamWorks. The fact that The New Yorker advertised a promotional interview with Spielberg on its cover by describing Saving Private Ryan as the film “to end all wars” was emblematic of the responses to the film elsewhere. Reviewers found it to be both serious and adult — further evidence of Spielberg’s growing maturity as a filmmaker, and a far cry from the money-grubbing cynicism and exploitative nature of something like Small Soldiers, which many of the most influential American film critics criticized for its violence, hypocrisy, and capacity to traumatize small children. No such criticism was waged against Saving Private Ryan because the much more graphic violence of the Normandy Beach sequence was taken to be a healthy jolt of reality, traumatizing only in a favorable sense by shocking the (supposedly adult) audience into a perception of the truth.

A characteristic phrase from New York magazine’s capsule review by David Denby is the assertion that Saving Private Ryan “blows every other World War II film out of the water.” The use of a violent military metaphor to justify a supposedly pacifist or at least semi-pacifist war film should be connected ideologically and syntactically with The New Yorker’s previously cited cover blurb — i.e., “the film to end all wars that blows every other World War II film out of the water” — in order to understand more precisely the sort of hypocrisy that Dante’s film exposes.

But I don’t mean to suggest that the dismissal of Dante’s work was exclusively the consequence of American publicity. An appreciation of the ethical force of Small Soldiers depends not only on a recognition of Joe Dante as a particular kind of satirist, but also on a sharing of certain generational attitudes, as well as on the timing of the release of Saving Private Ryan, which gave Dante’s film a pointed relevance for me. Put somewhat differently, Small Soldiers thrives on its contextual references whereas Saving Private Ryan succeeds with audiences only when its own contextual references are overlooked. The media was inattentive to the references to other war movies in both cases because these went against the critical profiles these films were supposed to have — crass business motives in the case of Small Soldiers, heartfelt reflections of real-life experiences in the case of Saving Private Ryan.

The essential auteur of Small Soldiers was perceived by many American spectators to be Burger King, a not-unreasonable assumption given the film’s promotional tie-in deals, not to mention the fact that, as I eventually discovered from Dante himself, Burger King had the final cut. In Locarno, the only hint of a tie-in or promotional gimmick came with the free hair gel handed out to spectators as a joke in conjunction with There’s Something About Mary, so audiences were freer to respond to the movie on its own terms. If Burger King indeed qualifies as the film’s auteur and Dante is merely its struggling metteur en scène, Small Soldiers can indeed be read as hypocritical; if the movie exists mainly to sell war toys and Dante can only work in the margins of this project by ridiculing selling war toys — and selling, buying, and consuming wars — then the whole enterprise has to be regarded as a machine turned against itself.

So the question of how adept some critics were in screening out the ridicule has to be joined with the question of how defenders such as myself managed to screen out Burger King’s ad copy. In the final analysis, the heart of the matter is the question of what a movie consists of — a viewing experience or the central object in a marketing campaign. Saving Private Ryan was mainly treated as the former and Small Soldiers the latter, which accounts in part not only for the discrepancy between the two responses but also for the overall failure of the press to perceive any meaningful relationship between the two movies.

***

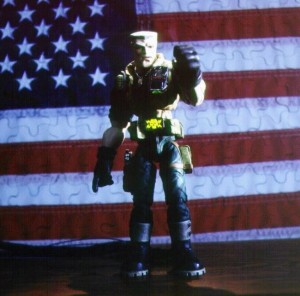

Beginning with a TV commercial for Globotech, a huge conglomerate that boasts converting weaponry into peaceful uses—“beating swords into plowshares for you and your family” — Small Soldiers whisks us off to the first meeting of Globotech’s CEO (Denis Leary) with two toy designers working for his latest acquisition, Heartland Play Systems. One of these designers, nerdy Irwin (David Cross) — a rough equivalent of Saki’s idealist hero — believes in making educational, nonviolent toys and has come up with a blueprint for benign, noble monsters known as the Gorgonites, creatures searching peacefully for Gorgon, their ancestral home. The other designer, hyper Larry (Jay Mohr), proposes the Commando Elite, a hard-ass squad of killer soldiers. Scoffing at Irwin’s qualms about violence and rationalizing his own preferences in movie-entertainment terms (“Don’t call it violence — call it action. Kids love action”), the CEO combines these two projects into a single line of products by designating the mainly white Commandos, miniature Schwarzeneggers and Van Dammes, as good, old-fashioned American destroyers and the Gorgonites as their multiracial targets and victims, then sends both designers off to produce high-tech toys within six months. Eager to please his new boss, Larry filches Irwin’s computer password and with it manages to acquire a microchip from the U.S. Defense Department, thereby empowering his Commandos with all the “action” they need.

When an early shipment of Commandos and Gorgonites is getting trucked through a small town in Ohio, a rebellious teenager named Alan (Gregory Smith), minding his father’s New Age toy store, the Inner Child, persuades the trucker (Dick Miller) to turn over one set of the new products on consignment, despite the fact that his father (Kevin Dunn) won’t stock war toys. Knowing that he can turn an easy buck by selling these toys on the sly while his father’s away at a seminar on small businesses, Alan represents another version of Larry and the CEO — let’s call it the entrepreneurial spirit — while his ineffectual father represents Irwin’s bumbling idealism. But once both Commandos and Gorgonites break out of their boxes and become engaged in a full-scale war—the Commandos programmed to search and destroy, the Gorgonites programmed to hide and eventually lose — the humans in Alan’s house and the family next door, including Christy (Kirsten Dunst), the girl Alan is pursuing—become caught in the crossfire and are forced to take sides. As the Commandos convert everyday domestic objects and appliances into weaponry, the grim undersides of consumer culture and kick-ass ideology come together in riotous, carnivalesque splendor.

Dante’s satire doesn’t simply target war and warmongering but the everyday cultural violence that encompasses them, by which I mean the violence in pop culture as well as the violence of pop culture. With the possible exception of Inner Space, just about all of Dante’s best work is concerned with this cultural violence, and part of the exciting achievement of Small Soldiers is to combine all of these concerns into one streamlined statement.

Part of the kick of Dante’s cheerful scorn is that it takes on not only the more obvious targets like The Dirty Dozen (by employing members of the original cast to speak the voices of the Commandos), but also the less obvious ones, like Apocalypse Now —already perceived by many as an antiwar film and hence something of a sacred cow, even in the nineties — while adroitly exposing the innate childishness of the overblown epic and heroic stances in all of them. The self-importance of a supposedly “balanced” portrait like Patton (Richard Nixon’s favorite movie) is made to seem just as ludicrous as an imperialist adventure like Rambo, and the consumerist aspect of war films in general is kept in the foreground. This pointedly includes the hypocrisy of such flag-waving “history lessons” as the exploded and severed body parts in Saving Private Ryan, which are contrived simultaneously to sell tickets and to provide moral correctives to other war movies — though the movies being corrected often upped the violence quotient in their own eras with identical rationalizations and mixed motives.

An ironic syndrome: every time a director decides to make a war film more graphic in its violence than its predecessors, the argument seems to be, “This’ll make someone think twice about wanting to go to war,” but the apparent result is to make young male spectators even more eager to prove their mettle by diving into such bloodbaths. It’s another version of the syndrome described in the Saki story, and one that has understandably prompted some critics to claim that there’s no such thing as an antiwar war movie — though Spielberg, perennial exploitation apologist, has recently claimed the reverse, that “every war movie, good or bad, is an antiwar movie” (presumably including Sands of Iwo Jima and The Green Berets).

It might be argued that self-deception is central to Spielberg’s achievements, as central to them as deceiving the public, because the two activities ultimately amount to the same thing. (Perhaps the apparent national desire to make Spielberg America’s official guru and poet laureate is predicated on an implicit understanding that he’s every bit as innocent about his motives as his audience — meaning that the audience knows it can safely remain innocent as long as he’s the grown-up in charge.) Audiences wouldn’t be nearly so susceptible to accepting the seriousness of Spielberg’s “grown-up” projects if he weren’t so adept at doing con jobs on himself. It surely takes a combination of innocence and show-biz smarts to convince an audience to contemplate the Holocaust by first getting them to identify with a Nazi who enjoys going to ritzy nightclubs. The same mentality led Spielberg to tell Stephen Schiff in The New Yorker that he received an enormous amount of pleasure from giving money to charities without telling anyone —without telling anyone, that is, except Schiff and his millions of readers. That’s why the same man capable of claiming that Jaws was “his” Vietnam and that “every war movie, good or bad, is an antiwar movie” can convince other people that Saving Private Ryan is something other than one more recruiting film.

I’ll never forget the experience I had escorting the late Samuel Fuller, the much-decorated World War II hero and maverick filmmaker, to a multiplex screening of Full Metal Jacket, along with fellow critic Bill Krohn, in Santa Barbara thirteen years ago. Though Fuller courteously stayed with us to the end, he declared afterward that as far as he was concerned, it was another goddam recruiting film — that teenage boys who went to see Kubrick’s picture with their girlfriends would come out thinking that wartime combat was neat. Krohn and I were both somewhat flabbergasted by his response at the time, but in hindsight I think his point was irrefutable. There are still legitimate reasons for defending Full Metal Jacket, in my opinion—as a radical statement about what conditioning does to intelligence and personality, as a meditation on what the denial of femininity does to masculine definitions of civilization, as a deeply disturbing experiment in sprung and unsprung narrative, and no doubt as other things as well. But as a piece of propaganda against warfare, it remains specious and dubious, providing one more link in an endless chain of generic macho self-deceptions on the subject. And for all its technical flair, it might be argued that the principal achievement of Saving Private Ryan is to extend that sort of self-deception into the nineties.

***

The fact that so many reviewers and other spectators didn’t perceive Dante’s efforts as satire about the consumption of war as spectacle or art is unfortunate but not entirely unprecedented. Tashlin, was equally misunderstood in the United States. Tashlin’s own vision of cultural violence was grounded in animated cartoons — he began as a cartoonist and animator — but the objects of his satirical and parodic scorn were somewhat different, tied to what was most aggressive about American pop culture in the fifties: comic books (Artists and Models); Hollywood (Hollywood or Bust); rock ’n’ roll (The Girl Can’t Help It); advertising (Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter?); television (Rock-a–Bye Baby); all kinds of media excess, sexual hysteria, loud colors, and gadgets (passim).

As a fan and aficionado of horror and SF movies as well as cartoons, Dante has a different spin on cultural aggression and what it consists of, but his fascination with the pop materials that he mocks and synthesizes rivals Tashlin’s, leading some commentators to conclude that he’s too invested in these materials to qualify as a satirist. Just as some critics found Tashlin too vulgar to qualify as a satirist of vulgarity, some critics today find Dante’s movies too violent to qualify as satires about violence. I would argue in both cases that the extreme stylization of both directors creates a sense of detachment about what they’re showing that is the true source of disturbance. Nothing is ever perceived as real in their comic fantasies, which means that viewers who want to participate are forced to reflect on their own reactions to what they’re watching, examine their own reflexes, and consider how much they’re the targets of what’s being satirized.

No doubt part of the failure of many American critics to perceive Small Soldiers as satire can be attributed to the habit of perceiving satire strictly according to the Swiftian model — the contempt for humanity in general and the audience in particular that infects, for instance, Dr. Strangelove, Wag the Dog, and The Truman Show, all relative favorites with critics and other industry “insiders” who pride themselves on their “media savvy.” The character played by Ed Harris in The Truman Show epitomizes this self-regarding image — a deity in the clouds who understands what the audience needs and wants with the proper amount of lofty condescension; the fact that Harris was honored with an Academy Award nomination for this performance only underlines the flattery.

From this standpoint, one of the most elucidating as well as disconcerting aspects of The Second Civil War is the degree to which Dante refuses to show contempt for any of his human characters, no matter how monstrous and misconceived their behavior might be. The contradiction in The Second Civil War between the dangerous xenophobia of the policies of the governor (Beau Bridges) and the affection he expresses for both his Mexican mistress (Elizabeth Peña) and Mexican food may be blatantly hypocritical, but rather than heap scorn on this character, Dante actually appears to like him; in effect it’s only the xenophobia that gets fully ridiculed. A similar refusal to treat any characters as pure villains characterizes the work of Tashlin, and the generational attitude associated with Dante’s satire is part of Tashlin’s legacy. It’s a legacy of both skepticism about and distance from the complex joys and perils of spectatorship — a legacy suggesting that Tashlin’s origins as a cartoonist and Dante’s as a film critic may represent two versions of the same basic impulse.

Small children seemed to have a much easier time picking up the satiric message of Small Soldiers than many of this country’s most prestigious film critics, suggesting the problem that “noise” — represented in this case by advertising and Burger King tie-ins, both of which helped to occlude Dante’s creative input — presents in assessing movies. Or maybe a likelier reason that film critics missed the point is their desire to assent to Spielberg’s patriotic warmongering, which Small Soldiers exposes with cheerful derision.