From the Chicago Reader (May 5, 1989). — J.R.

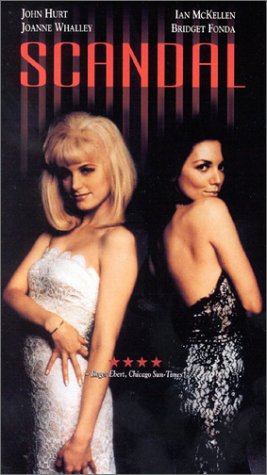

SCANDAL

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Michael Caton-Jones

Written by Michael Thomas

With John Hurt, Joanne Whalley-Kilmer, Bridget Fonda, Ian McKellen, Leslie Phillips, Britt Ekland, Daniel Massey, Roland Gift, and Jeroen Krabbe.

After applauding some of the forthright aspects of High Hopes and other recent English movies in this space two weeks ago, I’m happy to find my generalizations confirmed by a new English docudrama on the John Profumo-Christine Keeler sex scandal of 30 years back. Scandal, the first movie made on this subject, is good, clean, licentious fun.

While the titillating aspects of the story automatically place the film under the general rubric of “trash,” Scandal gleefully embraces its category without being unduly dumb or irresponsible about it. Starting off with an evocative period montage of the late 50s and early 60s, accompanied by the strains of Frank Sinatra’s recording of “Witchcraft,” the movie proceeds to unravel its complex narrative with a kind of polish that excludes any pretense of telling the “whole” story. (The project started out as a five-hour miniseries, and got boiled down to a feature after the BBC decided not to participate, but it is questionable whether the entire story could have been told even at miniseries length.) As a result of the film’s deliberate incompleteness, we can’t entirely account for all the motivations of the two leading characters — Dr. Stephen Ward (John Hurt) and Christine Keeler (Joanne Whalley-Kilmer), neither of whom, one should note, was a national figure before the scandal broke — and this works to the film’s advantage by giving the spectator some interpretive leeway in understanding just what happened.

![[Still]](http://prometheus.frii.com/~gnat/frii/movies/censorship/9.gif)

As far as the press was concerned, what happened in 1963 was that Christine Keeler sold a story to the Sunday Pictorial for 1,000 pounds stating that she had been sleeping with John Profumo, the British war secretary, as well as Eugene Ivanov, a Soviet naval attaché who was revealed as a possible spy. As revelation followed revelation, the popular British press had a field day; Profumo resigned from his post (he first denied the affair, then was proved guilty), and Stephen Ward — an osteopath and portrait artist of the rich and famous who had lived with Keeler, introduced her to both Profumo and Ivanov, and used her as an informant to help British intelligence — found himself being vilified as a pimp and abandoned by all his highly placed friends in the government, which ultimately drove him to suicide. Before the year was over, Harold Macmillan had stepped down as prime minister (ostensibly for reasons of health), and the Conservative government was defeated in the next year’s election, ushering in a 15-year period of Labor Party domination.

Although it’s tempting to try to link the Profumo affair to the recent trial by press of Gary Hart (among others), the effect of politicians’ sexual behavior on their political careers has had very different and nonsynchronous histories in England and the U.S. As English writer Graham Fuller points out in the current Film Comment, Grover Cleveland could admit to having fathered an illegitimate child in 1884 and still be elected president, but ever since Ted Kennedy’s debacle at Chappaquiddick, the American media and public have been less forgiving about tarnished public profiles. By contrast, Cecil Parkinson’s adulterous affair with a secretary who became pregnant, which ejected him from England’s Department of Trade and Industry in 1983, didn’t keep him from being named as Margaret Thatcher’s energy secretary last year.

One conclusion that might be drawn from the fickle attitudes of the public about such behavior in both countries is that public responses to the private lives of government officials are seldom consistent or logical but are rather reflexes to the political moods of individual historical moments. Presumably, the same public that voted in a Conservative government licked its chops when the yellow press helped to cause that government’s collapse. A similar sort of capriciousness can be seen in the American public’s indifference to Watergate before Richard Nixon’s re-election and its obsession with Watergate afterward — a return of the repressed that is no less apparent in this country’s shifting tastes in clothes, politics, movies, erotic and cultural fashions, and pleasure itself.

It’s to the credit of Scandal that it treats the Profumo affair as a manifestation of its own period rather than as a timeless parable or a story with a particular moral. Much of the movie is about the sheer elation of the energies that were set loose in the early 60s, and the grim aftermath of this elation for some of the individuals involved is treated refreshingly neither as poetic justice nor as divine retribution — the standard Hollywood forms of comeuppance — but simply as what happened.

The osteopath-artist Stephen Ward, a central character in the story as it’s told here, remains in some ways the most ambiguous and mysterious figure in the scandal. The son of a clergyman — one of the traits that he interestingly shares with John Hurt, the actor who plays him — he studied medicine in the U.S., then returned to England to set up practice in the seaside resort of Torquay. Stationed in India during World War II, he became a member of the local jet set, but was hospitalized toward the end of the war for some sort of nervous collapse. Back in England, he joined a London clinic and became known for his famous clients, the first of whom was Averell Harriman (who was then U.S. ambassador to Britain); before long, he established his own practice, where his patients included Winston Churchill, J. Paul Getty, Ava Gardner, and Elizabeth Taylor. He was also connected with the British royalty, and enjoyed the use of a weekend cottage on Lord and Lady Astor’s Cliveden estate.

Scandal‘s story more or less begins when Ward meets Christine Keeler in 1959 at Murray’s Cabaret Club, where she is working as a show girl, and actively pursues her. Taking her under his guidance a la Pygmalion and comparing her to a racehorse (which, by implication, he would like to train), he convinces her to revert to her natural hair color (from bleached blond to brunette), removes her false eyelashes, takes her shopping, installs her in his flat, and begins to introduce her to some of his classy friends — without showing any interest in having sex with her. Apparently voyeuristic in his attraction to her, he delights in initiating her in some of the sexual games enjoyed by his set, such as planned orgies, and then chatting with her about them afterward. (Ward himself is a participant in these orgies, but we don’t get a very clear sense of how he behaves in them.) When Christy befriends another show girl named Mandy Rice-Davies (Bridget Fonda), the latter moves into Ward’s flat and social circle as well, and both women work as models as well as semicourtesans, accepting cash gifts from their wealthy dates.

Approached by British intelligence and asked to report on his Soviet friend Eugene Ivanov (played by Dutch actor Jeroen Krabbe), whom the intelligence agents suspect of espionage, Ward readily agrees, and he encourages Christy to get involved with Ivanov so that he can get more information that way. A lover of gossip and intrigue, Ward also is instrumental in getting Christy acquainted with war secretary John Profumo (Ian McKellen) at the same time, but after an affair between Keeler and Profumo develops, Ward’s reputation as a big talker makes their liaison too high a risk, and Profumo asks her to either move out of Ward’s flat or break off their affair. Although Keeler insists that Ward isn’t her boyfriend, she insists on remaining where she is.

All these intrigues eventually become public in late 1962, after two of Keeler’s less well-to-do lovers, both of them West Indian, get into a knife fight, and one of them turns up outside Ward’s flat with a gun. Ward, angry at this ugly exposure, asks Christy to move out, and she retaliates by selling both her story and a letter from Profumo to the Sunday Pictorial.

Given all this trashy material (and more), the movie keeps itself bracingly free of easy moralism and glib conclusions; simply put, there are no villains in sight, and no pure heroes either. One of the principal virtues of Michael Thomas’s script and Michael Caton-Jones’s direction is that the overall view presented is balanced without ever seeming static. This is Caton-Jones’s first feature, but he already seems to function like a pro. He does indulge in some fancy uses of slow-motion and close-ups — which culminate in a gigantic image of Ward’s last unfinished cigarette crashing to the floor — but generally he seems to know that splashy effects of this kind don’t increase our knowledge of the characters or situations; they only help to dramatize the unanswered questions or heighten the erotic charge of certain moments.

Even Ward, who winds up as the major victim and scapegoat — and, thanks to the effectiveness of Hurt’s performance, is treated with a great deal of sympathy and depth — is spared a one-sided treatment; the casual racism that he reveals in a reference to “jungle bunnies” when he asks Keeler to move out of his flat is certainly not made to seem either exemplary or urbane. In keeping with the same principle, the unconventional love story between Ward and Keeler that serves as the movie’s central focus is neither romanticized nor deromanticized; it isn’t precisely defined or digested for us, so we have to make up our own minds about it — or, better yet, suspend judgment altogether.

On the other hand, it would be wrong to claim that Scandal presents its story without any pronounced moral biases. On the contrary, it is unambiguously positive and celebratory in its treatment of the characters’ carnality, hedonism, and tolerance of kinkiness (a nude guest serving as waiter at an orgiastic cocktail party bears a sign reading, “Please beat me if I fail to satisfy,” and Mandy obliges by slapping his offscreen penis with a rose). One would be hard put to find any recent American mainstream movie as guiltless and as accepting about such matters. Horror of horrors, this movie doesn’t even condemn the casual prostitution of Keeler and Rice-Davies, but makes it look like fun for all the parties involved.

(Apparently the orgiastic cocktail party was too much fun in its original English form to qualify for an R rating in this country, so some footage of straight screwing in this scene was cut from American prints. Presumably if this sequence had a higher moral tone in the American vein — say, a few knife slashings instead of guiltless intercourse — it wouldn’t have been threatened with an X.)

(Another aside: Joe Boyd, one of Scandal‘s executive producers, has pointed out that in 1961, the same year that Keeler was carrying on simultaneous affairs with Ivanov and Profumo, the queen’s counselor who was to prosecute Ward two years later for pimping — groundlessly, as it turned out — was prosecuting the publishers of [and successfully banning] Lady Chatterley’s Lover, asking the jury if they would want their servants to read such a book.)

Insofar as “yellow journalism” serves on occasion as an indirect political forum for the working class, the conflation of class revenge with sexual outrage undoubtedly fueled the Profumo scandal that followed, and the fact that Ward came from the middle class probably had as much to do with his abandonment by his wealthy friends as the sexual predilections that they surreptitiously shared with him. In effect, the closing of ranks in “gutter” journalism and the upper classes alike left a social climber like Ward out in the cold, without a toehold in either realm. But this is only one possible theory about the volatile cocktail of elements that Scandal deals with; one of the strengths of the movie as a whole is that it encourages us to reach our own conclusions.