From the June 1982 American Film. — J.R.

Fans of the brilliant, eccentric, and pioneering film critic Manny Farber who have been regretting his recent absence from the scene simply haven’t been looking in the right places. In fact, the sixty-five-year-old writer, teacher, and former carpenter has been a painter even longer than he’s been a critic, and over the past few years he’s been doing what he calls “auteur” paintings — canvases that recast the subjects and methods of his criticism in a number of fascinating ways.

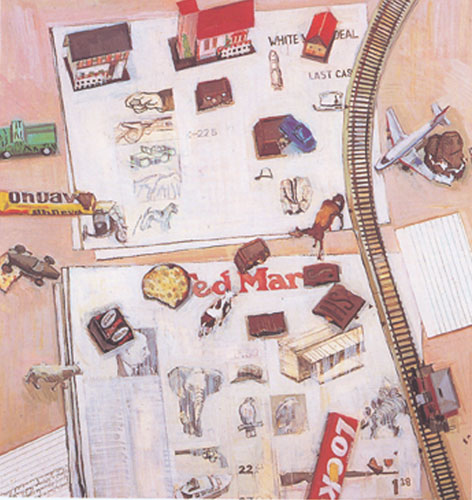

Using a bird’s-eye view of small objects on a stagelike platform, his paintings, paens to such directors as Howard Hawks [see Howard Hawks II, 1977, 472 x 500, above], Sam Peckinpah, Marguerite Duras, and William Wellman illuminate the filmmakers’ styles and themes. “The compositions and structures are always always based on my take on the directors,” Farber says. “And they’re critical in the fact that I’m usually going away from what I think is known territory, in painting as well as in movies.”

One example of Farber’s oddball approach is his Stan & Ollie, which is full of references to the comedies of Laurel and Hardy, but scarcely uses their faces at all. “I wouldn’t dream of doing anything that would be that easy or straight — it would seem corny to me,” Farber explains, going on to describe his strategy of seeing all their films as minimal one-to-one compositions — one body, object, shape, or mass against another. (The painting was originally called 1 + 1.)

In the case of Thank God I’m Still an Atheist, his 1981 tribute to Luis Buñuel (535 x 420 in size), Farber is playing with all sorts of toys and objects that are distinctly Buñuelian. Tarotlike cards bear stray phrases, words, and images — “de jour” from Belle de jour, “Rey” from Fernando Rey, a cow from L’age d’or, a bell from Tristana.

Some details are puns expressed in rebus form, so that one card with a milk bottle beside another with a licking tongue and the word “way” equals The Milky Way. Small boxes labeled “1. vehicles” and “2. junk of little importance” seem to denote Farber’s particular affection for Buñuel’s Mexican B-films. On the right, beside a watermelon slice and a lynx, is an eye violated or stabbed by a cross — which illustrates the way that Catholicism (the crucifix) and Surrealism (the sliced eye of Un chien andalou) are often virtually interchangeable in Buñuel’s movies.

In addition, according to Farber, “the painting’s whole compositional strategy was based on that zigzag walk that the hero of El does — up the big staircase, or across the institution grounds at the end –whenever he’s in a fury of psychological frustration and anger. That always struck me as one of the most beautiful Buñuelisms, and so instead of a serpentine circling out of this circular painting, I decided to do a zigzag. It made that picture enormously difficult, because it’s a hard thing to pull off. Critically, it’s trying to do something with the black humor of Buñuel almost all the way through.”

Farber’s paintings have been exhibited in New York, Washington, D.C., Philadelphia, and La Jolla. The next showing is being planned at the Gagosian Gallery in Los Angeles. — Jonathan Rosenbaum