From the Chicago Reader (March 26, 1993); reprinted in my collection Movies as Politics. — J.R.

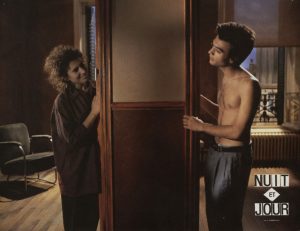

NIGHT AND DAY **** (Masterpiece)

Directed by Chantal Akerman

Written by Akerman and Pascal Bonitzer

With Guilaine Londez, Thomas Langmann, François Negret, Nicole Colchat, Pierre Laroche, and Christian Crahay.

Considering all the oppositions that inform the work of Chantal Akerman — such as painting versus narrative, France versus Belgium, being Jewish versus being French and Belgian, and the commercial versus the experimental — it’s only logical that both the plot and the title of her recent Night and Day, one of her best features to date, should reflect the same pattern. The situation it refers to is so simple that it’s hard to describe without making it sound singsongy: Julie (Guilaine Londez) and Jack (Thomas Langmann) — an infatuated young couple from the provinces who’ve recently come to Paris — live in a small flat near Boulevard Sebastopol. During the day they make love; at night Jack drives a taxi and Julie walks the summer streets, singing happily to herself. One night they meet Joseph (François Negret) — another isolated newcomer to Paris — who drives Jack’s cab during the day. Jack heads for his shift; Julie goes walking with Joseph, and they quickly fall in love. From then on, Julie becomes a round-the-clock lover, sleeping with each driver as he gets off work; Joseph knows about Jack but not vice versa, and Julie refuses to choose between them. (She eventually arrives at what might be called the ultimate feminist solution.)

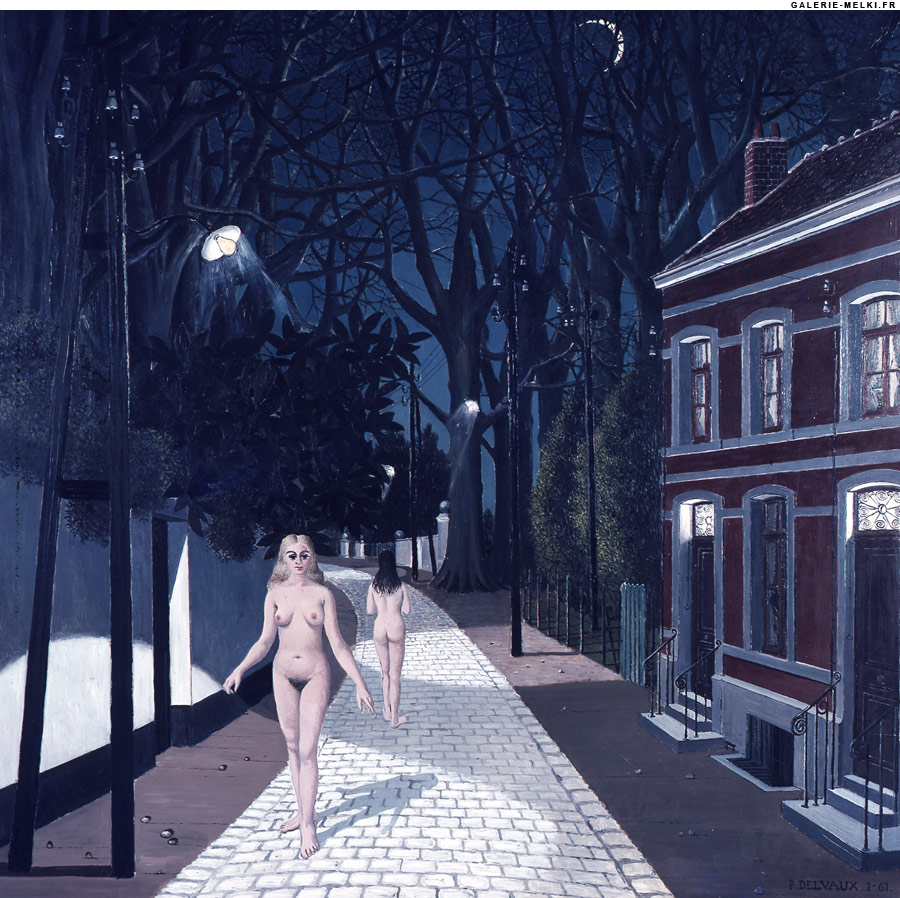

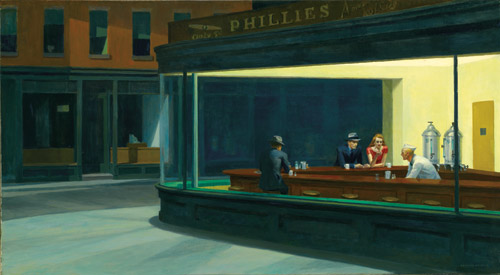

Insomnia has long been a basic element of Akerman’s nocturnal poetics — especially in Les rendez-vous d’Anna, Toute une nuit, and The Man With a Suitcase. But until now Akerman’s take on it has seemed troubled and neurotic. Her magically luminous nighttime exteriors and claustrophobic interiors, like those of her painterly influences, Belgian surrealists Paul Delvaux and René Magritte as well as Edward Hopper, glower with abnormal degrees of presence. á à

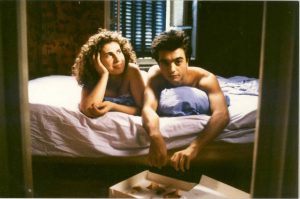

In Night and Day, by contrast, insomnia seems a kind of precondition for utopian romance — a sentiment expressed at the very outset by Jack and Julie as they lie together in bed: “Are you sleeping?” “No. Are you?” “No.” “You and I never sleep.” “Never when we are together.” “We like movement better.” “Yes, it’s true.” “When I sleep, I don’t live.” “Neither do I.” “Right now, I prefer living.” “So do I.”

A little later their dialogue resumes: “Maybe we should meet people.” “Next year.” “And get a telephone?” “Next year.”

And finally, after they make love, this closing exchange: “You must sleep, Jack. You’ll have an accident.” “Next year.”

The musical-comedy-like rhythms of their dialogue are far from accidental. Roughly speaking, Night and Day is Akerman’s third and most successful attempt at capturing the feel of a musical — after Les années 80 (1983), an inspired feature-length trailer for one, and Golden Eighties (aka Window Shopping, 1986), a charming if somewhat disappointing fulfillment of the earlier prospectus. This one succeeds in part because it’s less literal in this endeavor than its two predecessors.

A ravishingly beautiful moment immediately follows the above dialogue: Julie starts to sing wordlessly along with the lush strings on the sound track — sometimes in unison, sometimes complementing or augmenting the musical backdrop. After she and Jack walk downstairs to go their separate ways — he to his taxi, she on her nightly tour of the city — she begins to sing out loud to the same tune, this time without accompaniment, a kind of celebration of her life as we’ve come to understand it. “During the day, he tells me about his night, and at night I wander across Paris. . . . We don’t have a child; it isn’t really the right time. . . . I always get home before him. I wait for the day and erase the night. It’s summer in Paris, the time for abandonment, when days are the longest. . . . We don’t have a phone, but we don’t know anyone anyway.” Sometimes we see her singing while she walks and sometimes we merely hear her offscreen, but the movement of her walk and the movement of the melodic line both proceed continuously in a stream of unbroken poetry.

Not all of Night and Day proceeds like a musical. Indeed, the sheer exuberance of the first reel or so isn’t really sustained over the film’s 90 minutes. At the same time, it would be shortsighted to assume that capturing the spirit of musicals represents the sum of Akerman’s ambitions here. To try to understand better all that Night and Day achieves, both in relation to Akerman’s earlier work and on its own terms, it would help to return to the four separate, yet connected, oppositions already mentioned.

***

Painting versus narrative. “Carl Dreyer’s basic problem as an artist,” wrote the late Robert Warshow in 1948, reflecting on Dreyer’s Day of Wrath, “is one that seems almost inevitably to confront the self-conscious creator of ‘art’ films: the conflict between a love for the purely visual and the tendencies of a medium that is not only visual but also dramatic.” This is the problem addressed in one way or another by each of Akerman’s features to date, beginning with her painterly, silent, nonnarrative first feature, Hotel Monterey (1972), made in New York when she was only 22, and her narrative and relatively unpainterly sound feature Je, tu, il, elle, made two years later.

Her 1975 masterpiece Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles was her first major attempt to combine and somehow reconcile the visual with the dramatic, and the features that follow represent different attempts at synthesis. News From Home (1977), for instance, is essentially a nonnarrative study of Manhattan exteriors accompanied by Akerman’s voice as she reads letters she received from her mother while she was in New York, material that inevitably introduces narrative elements. Les rendez-vous d’Anna (1978), The Man With a Suitcase (1984), and Golden Eighties are all unabashed story films, but the first two make use of some of the claustrophobic painterly elements in Hotel Monterey, while the third, set almost entirely inside a small shopping mall, defines narrative as an interlocking series of mini-plots.

Toute une nuit (1982) is also made up of multiple mini-plots, but other than occurring over a single night most of them don’t interlock, and the overall effect is more painterly than narrative; the same is true to an even more radical extent of Histoires d’Amérique (1989), which stages the recounting over one night of numerous Jewish jokes in and around a Brooklyn park. Les années 80, a documentary about Akerman auditioning and rehearsing actresses for Golden Eighties, regards these actresses in part as painterly subjects or models and incorporates narrative only in the sense that it charts the development of certain songs and performances.

In broad terms, the polarity between painting and narrative is one between persistence and development. A painting exists in space, a narrative in time; persisting is what a painting does in time, and developing is what a narrative does in space. Consequently, insofar as Akerman’s films resemble paintings, character and plot development is always something of a problem, and insofar as they impose narratives, the persistence of people and places without any development is also something of a problem.

In the past, camera movements in Akerman’s work have tended to be both functional (pans following the movements of actors) and minimal, with the consequence that most of her compositions are static and therefore painterly. In Night and Day, camera movements have become copious and descriptive as well as functional; that is, they not only follow, accompany, or precede Julie when she walks down the streets of Paris or from room to room in her flat, but also lyrically traverse the bodies of her and her lovers when she’s in bed with them. One might say, in other words, that they follow or impose narratives on the people and the places, her painterly subjects.

France versus Belgium. Akerman was born in Brussels in 1950, and Belgium remains an important setting in many of her works, including Saute ma ville! (her first short, made in 1968), Jeanne Dielman, Les rendez-vous d’Anna, and Toute une nuit. The relatively staid and repressive quality of Belgian culture — including the bourgeois aspects of Belgian surrealism as exemplified by painters like Delvaux and Magritte — has a great deal to do with what these films are about as well as what they’re like, which is why they’re so much creepier than Akerman’s other works. Their decorous sense of the everyday calls to mind what the English writer and broadcaster George Melly once said about Magritte: “He is a secret agent, his object is to bring into disrepute the whole apparatus of bourgeois reality. Like all saboteurs, he avoids detection by dressing and behaving like everybody else.”

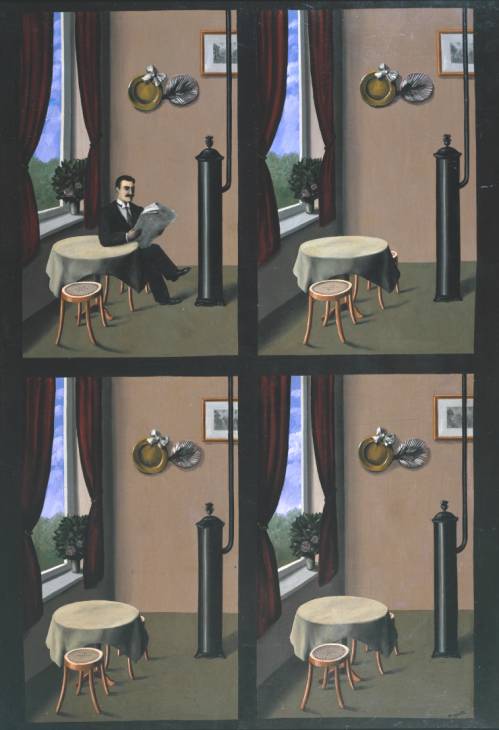

Magritte’s Man With Newspaper (1927-’28) tells me something about the customary disquiet of Akerman’s world. In it, four panels, two on top and two on the bottom, show the same corner of a sitting room, with one difference: in the first panel a man is seated at the table by the window reading a newspaper, and in the other three panels, neither the man nor the newspaper is in evidence. A narrative is implied between the first and second panel — the disappearance of the man and newspaper — without being confirmed, and we’re left with the eerie fact of three identical “empty” rooms. Similarly, many of Akerman’s settings suggest absence even more than presence.

Night and Day, like many of Akerman’s recent films, is a French-Belgian coproduction, but it has less of this creepy quality than any of her films I’ve seen to date. There’s some evidence that France has been a liberating force in her work, sexually as well as stylistically. Figuratively, at least, one might say that for the first time in her work, there are no empty rooms.

Being Jewish versus being French and Belgian. Akerman is the daughter of Polish Jews who survived the Nazi concentration camps, and this background bears significantly on News From Home, Les rendez-vous d’Anna, and Histoires d’Amérique. Though Thomas Langmann, the actor who plays Jack, played the Jewish leading character in a non-Akerman feature, Les années sandwiches (1988), and Guilaine Londez (Julie) has a physiognomy that suggests she might be Jewish, Jewishness appears to have no thematic relevance in Night and Day, and to all appearances seems as unimportant here as Akerman’s Belgian background. Significantly, however, Night and Day immediately follows Histoires d’Amérique, which is the most explicitly Jewish and, quite possibly, the least commercially successful of all her features to date. (Its critical reception at the Berlin film festival in 1989 was generally hostile and it appears to have had few screenings since then.)

The commercial versus the experimental. Throughout her career, Akerman has been commercially ambitious at the same time that she has shown the marked influence of experimental and mainly nonnarrative filmmakers such as Michael Snow, Stan Brakhage, and Jonas Mekas. In Je, tu, il, elle she took her first major steps toward commercial features, introducing sex as well as narrative into her universe while implicating herself personally by playing the lead character. In Jeanne Dielman, for the first time, she cast a movie star (the late, great actress Delphine Seyrig) in the lead role, while in Les rendez-vous d’Anna she moved closer to articulating a conventional story line. Les années 80 and Golden Eighties, by virtue of their charismatic casts and songs, clearly represent further attempts to woo and seduce audiences.

While Night and Day doesn’t qualify exactly as Akerman’s first love story — Golden Eighties is full of love stories — it is probably her first love story that audiences can easily identify with. Similarly, it is certainly not her first feminist film, but possibly the first that could be described as commercial. (The ads, not inappropriately, refer to it as “a postfeminist romance.”)

***

One might conclude that Akerman has taken a big step with Night and Day toward making a conventional narrative feature. But the painterly persistence remains throughout the film; Jack and Joseph’s physical resemblance, the repetitions of various camera movements and angles, the similarities of Julie and Joseph’s various hotel rooms, and the recurrences of some Paris locales (such as place de Chatelet and rue de Rivoli) are all manifestations of this. And these rhyme effects have thematic as well as stylistic consequences. (Julie’s nightly routines become increasingly ritualistic, and at times the two male lovers seem interchangeable.) On the other hand, it might be argued that these rhyme effects are ultimately less painterly or narrative than they are musical; if the film’s music gradually decreases in importance, and disappears entirely in the final sequence, one might argue that the film’s rhythms have by this time been taken over by certain visual refrains. (Throughout the film, the feeling of summer nights in Paris is so palpable that one can almost taste it, and this delicious taste may be the film’s loveliest achievement in painterly persistence.)

It might be argued that narrative development — which includes character development — remains something of a problem, even if Akerman’s attempts to solve this problem are pretty ingenious. Toward the end of the film, Julie and Jack decide to knock out a wall in their flat, largely as a means of rejuvenating their own relationship. The physical change in their apartment leads them to throw a party — a major change in their relationship. Julie, we’re told by an offscreen narrator, subsequently undergoes an even more important change, but the fact that we’re told about this change rather than shown it indicates to what extent narrative development eludes Akerman — at least formally and dramatically, if not thematically.

This offscreen narrator is in fact an integral part of the film. Her all-knowing and somewhat personal commentaries on the action may remind us, along with the names Jack and Joseph, of Francois Truffaut’s Jules and Jim, a classic — and classically romantic — French New Wave depiction of a ménage à trois as well as of a free-spirited woman who makes all the significant moves and calls all the shots. But the offscreen narrator of Jules and Jim is a man, not a woman — a conventionally patriarchal voice-of-God narrator who ultimately articulates the male viewpoint that Jules and Jim embodies, merging the viewpoint of Truffaut with that of Henri-Pierre Roche, on whose autobiographical novel the film is based. It’s a voice whose narrative authority we’re meant to accept without question.

Simply because of this patriarchal convention, it’s hard to hear the woman narrator of Night and Day without asking — even if only momentarily — who this woman is. Once we ask this question, however, the answer becomes clear: she is the woman Julie will become. The story she tells is the one about how Julie becomes her.