From the Chicago Reader (February 10, 1989). — J.R.

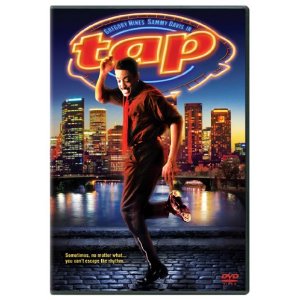

TAP

** (Worth seeing)

Directed and written by Nick Castle Jr.

With Gregory Hines, Suzzanne Douglas, Savion Glover, Joe Morton, Dick Anthony Williams, “Sandman” Sims, Bunny Briggs, and Sammy Davis Jr.

One of the more poignant effects of contemporary Hollywood has been the virtual extinction of at least two of the major genres that served as industry staples during the 30s, 40s, and 50s: the western and the musical. When attempts are made to resurrect these old standbys, a certain self-consciousness often makes itself felt. Such “last westerns” as Once Upon a Time in the West and McCabe and Mrs. Miller, and such “last musicals” as All That Jazz and Pennies From Heaven tend to wear their obsolescence on their sleeves, representing themselves as last-ditch attempts to revivify forms that are no longer part of the present tense, but only nostalgic emblems of an earlier era.

Other recent approaches, however, have avoided such self-consciousness, and behaved as if the genres in question never really left us. Young Guns was a fairly forgettable attempt to bring back the western that populated a conventional example of the genre with several youthful male stars. Tap is a somewhat better and more equivocal effort to bring back the musical — specifically, the urban depression musical — without attempting to make any self-reflexive statements about what that form means in a contemporary context.

The traditional aspects of Tap, as a depression musical, don’t include a period setting — the film takes place in the present — but it does draw on many of the plot and musical elements that one associates with 30s musicals. One example is the sentimental, simplistic plot, in this case about a young, talented hoofer named Max Washington (Gregory Hines) who has to choose between following in the footsteps of his gifted but unsuccessful tap-dancing father and pursuing a life of crime with a gang of jewel thieves. Other traditional elements are the sense of community and camaraderie that persists in the upper rooms of the tap-dance school established by Max’s late father, a conventional romance between Max and Amy (Suzzanne Douglas), who currently runs the dance school, an equally conventional father-son relationship between Max and Amy’s son by a previous marriage, and a straightforward and unironic approach to the various dance numbers, all of which arise naturalistically in the action.

Some of the less traditional aspects of Tap as a depression musical are no less striking, even if the movie fails to make an issue out of any of them. Most of the leading characters are black, and though there are certain white characters in this milieu — including the boss of the jewel thieves, the director of a Broadway musical that Max auditions for, and a number of the tap dancers and tap-dancing students — none of them serve in any way as audience identification figures. Most of the musical numbers are pithy and often disappointingly short; there are no extended performances of the kind that one associates with the Busby Berkeley musicals of the 30s. And the movie occasionally makes use of a postmusical tradition that entails the offscreen playing of pop music over the action, a procedure familiar from such relatively recent films as Saturday Night Fever and Flashdance.

The combination of these various elements occasionally produces a few jarring gear changes: for instance, after Max and Amy perform their “black Fred and Ginger” dance routine to a record of “Cheek to Cheek” on the rooftop of the dance school, Sonny’s Side of the Street, they make love to an offscreen disco tune in one of the empty studios below, and it momentarily feels as if we’ve passed from one movie to another in a matter of minutes. The “black Fred and Ginger” number, which is suavely executed by Hines and Douglas, is the movie’s only direct reference to the 30s musicals. (It is worth adding that writer-director Nick Castle Jr. is the grandson of ballroom dancers Vernon and Irene Castle, who were portrayed by Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers in their last 30s vehicle.) As Jane Feuer points out in her sprightly academic guide The Hollywood Musical, references in musicals to earlier musicals are a standard feature of the genre.

Feuer deals with another subject in her book that has a particular relevance to Tap — the dialectic between bricolage and engineering. Bricolage, the French word for tinkering, used by anthropologist Claude Levi-Strauss to refer to processes by which prescientific cultures made use of whatever materials happened to be at hand, in this context describes the process by which performers in musicals take over everyday objects and locations and convert them into props and theatrical settings. The process usually involves an easygoing, improvisational attitude toward one’s surroundings that masks the actual work and planning that dancers, choreographers, and set designers (among others) engage in for a musical number. Part of the pleasure that we ordinarily take in a dance number derives from its seemingly effortless and spontaneous execution, and much of the “work” of a musical is devoted to making its numbers come across as anything but work.

One of the most exciting numbers in Tap occurs when Max is asked to perform at a nightclub where his late father used to dance. Taking the audience out into the street with him, Max begins to demonstrate how his father’s inspirations were not so much the moves of other tap dancers as the everyday sounds of New York. Moving to a nearby construction site, Max proceeds to create his own form of bricolage, converting ordinary industrial sounds into vocal riffs, which are translated in turn into dance steps, and much of the audience promptly joins in.

If Tap were a more accomplished musical than it is, the number would have been filmed in relatively long takes that respected its integrity and continuity. The rapid editing employed isn’t quite as ruinous as it is, for example, in The Cotton Club and in many music videos, where flashy montage effects detract from the dancing rather than enhance it, but it does manage to leave one feeling a little unsatisfied by the number’s only partially fulfilled promises –i t finally proves to be two parts windup to one part delivery, ending before it gets a chance to work up a proper momentum.

It may ultimately have been budgetary restrictions or a certain lack of self-confidence that led Castle (or choreographer Henry Le Tang) to end most of the numbers prematurely. Fortunately, the movie has a number of other compensations. David Gribble’s cinematography, which makes a striking use of diffused lighting, gets some interesting color effects from many of the movie’s settings: the blue gray cell in Sing Sing where Max practices his tap steps at the beginning of the movie, the lemon-colored light in the practice rooms at Sonny’s Side of the Street, and some of the honey tones employed elsewhere. Sammy Davis Jr. plays Little Mo, Max’s tap-dancing mentor and a kind of surrogate father, with a cane and no effort to disguise his age; it’s a character part rather than an attempt to milk his usual show-biz persona, and he pulls it off with charming aplomb.