From The Financial Times (Friday, July 2, 1976). This was the second and last time that I took over Nigel Andrews’ weekly film column while he away. — J.R.

Bambi (U)

Odeon, St. Martin’s Lane

Lifeguard (AA)

Ritz

When the Leaves Fall

National Film Theatre

Thirty-four years have passed since Walt Disney’s Bambi first hit the screen. Yet barring only its quaintly dated musical score – six unremarkable tunes by Frank Churchill and Edward Plumb that are well below the usual Disney standard – an unsuspecting child who can’t read Roman numerals might assume that it was made yesterday. It is no small irony that a movie only slightly more than half as old, Silk Stockings (1957), gets treated like a museum piece worthy of nostalgia in the recent That’s Entertainment Part II, while this animated feature gets born afresh for each new generation – not so much like a phoenix rising out of its ashes as like a display of calendar art circulated periodically, with only the dates changing.

One element undoubtedly helping to sustain this timelessness is the cast of characters; unlike Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, Pinocchio and Dumbo, the feature-length Disney cartoons preceding it, Bambi pitches its tent outside civilization, in a paradisal forest kingdom where mankind figures only obliquely and obtrusively, as evil intruder and destroyer. Perhaps for this very reason, it offers an ideal laboratory specimen of an apparently innocent and harmless confection that in fact exudes ideology from every pore.

Consider the movie’s ostensible message: an ode to the beauty, harmony and intrinsic goodness of nature undisturbed by man. Visually, the entire film bears witness to this exalted pantheism through its lyrical grasp of the colours, textures and shapes of the vegetable and mineral world –a sensitivity especially evident in the opening shot, when the camera glides mysteriously through the folds of a misty forest interior, past a waterfall and sparkling spring which glisten among the trees and other plants like precious jewels.

But then the animals come into the picture and their relationship to real animals is so remote that they reflect a reverse attitude: a loathing and fear of the natural works that seeks to smother every remotely disturbing and/or inhuman part of it with cotton candy. Among the forest population we find a wise, grumpy old owl patterned after a cliché version of a folksy uncle dispensing such wisecracks in response to the courtings of springtime as “‘Love’s sweet song’ — pain in the pin-feathers, I call it” and “They’re twitterpated”; a chipmunk who sleeps cuddled under another chipmunk’s tail; smiling, chirping baby birds; a rabbit named Thumper who looks and sounds a little like Mickey Rooney imitating a toddler — all of whom rush together in the opening scene, joined by legions of their neighbours, to witness the birth of the title hero, a deer.

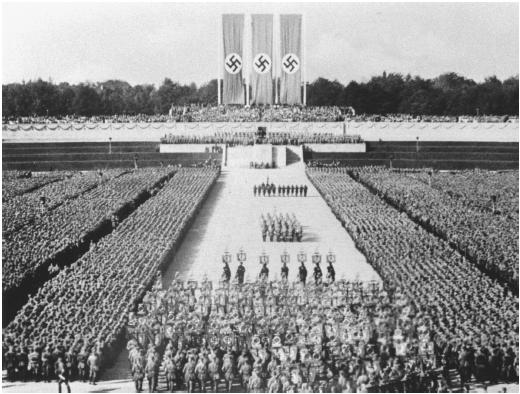

The notion of all the inhabitants of a forest moving and responding like a single emotional unit is one that we’ve met elsewhere, in Snow White, where the entire animal community unites with the co-ordinated hysteria of a lynch mob to warn the seven dwarfs about the Wicked Witch’s evil design on the heroine< here the impulse is positive, but the sense of mystical communion is no less pronounced; and to find its human equivalent in 1942, the year Bambi was first released, one has to look not at America but at the exalted myths of social unity that were prevalent in Nazi Germany at the time.

If the point seems forced or fortuitous, a closer look at the ingredients of Disney’s style may be in order. Of all live-action directors, the one whose vision and manner most nearly approximate his is Leni Riefenstahl, the gifted poet laureate of Hitler’s Germany (in Triumph of the Will and Olympia) whose first film, The Blue Light (1932), astonishingly anticipates Bambi in many particulars. There, too, one finds a hymn to the spectacular vistas of nature and the telepathic cohesion of its gentle inhabitants, as well as the greed and brutality of outsiders who despoil its riches. And in Riefenstahl’s best known film, Triumph of the Will (1934), which charts the massive Nuremberg rally held the same year, the heroic camera angles accorded to celebrated Nazi leaders towering over crowds are echoed in the first glimpse we have of Bambi’s father, an elk poised proudly on a mountain ledge high above the scene of his son’s birth. Significantly, it is Bambi himself who assumes this lofty pose — first alongside his father, and then alone — in the movie’s final image. Bearing all this in mind, it may not be entirely coincidental that when Riefenstahl visited Hollywood in 1938, Disney was reportedly the only film celebrity there to greet her warmly in public.

From another standpoint, the chief subject of Bambi is the concrete conditions of growing up as human beings, not animals, experience them: learning to speak and walk, making friends, undergoing the rites of adolescence. Even here, the facts are often idealised beyond ordinary recognition. Battling with the horrifically savage dogs of the hunters, Bambi gets virtually chewed to bits without bleeding a single drop, and his amorous cavortings with Felice, a female deer, are rendered in the manner of the best Hollywood mush. (Needless to say, sexual difference is chiefly made apparent by her fluttering eyelashes.)

If one added up all the cosmetic “improvements” supplied by Disney animators to animals, one would have a fantasy system quite analogous to the ones yielded by air-brushes in many sex magazines. But eliminate all the moving critters from Bambi and you will find something at least halfway suggestive of a genuine pantheism. For all of Disney’s kitschy effects, he can convey a sense of wonder about plants, rocks and water that goes far beyond the drippy cuteness and cigar-box banality of his characters.

*

At this point in the long hot summer, when most of the exciting new films are snugly tucked away to await autumn openings, one can almost feel grateful for a bad movie that doesn’t kick you in the teeth with its strident awfulness and then ask you to like it. Lifeguard — one of the closest things I’ve ever experienced to visual Muzak — uses an altogether gentler form of persuasion. Languid pans across a beach, schmaltzy softcore sex, a cast which seems to be composed exclusively of photographic models, and wholesome surfing music to fill in the many gaps all add up to an inoffensive entertainment, designed to be received in a state of semi-consciousness. Although the title might suggest something existential or allegorical, like Pickpocket or Taxi Driver, the subject here is a lot more gritty and basic: should a handsome lifeguard in his mid-thirties accept his friend’s offer of a job selling Porsches, or should he stick it out on the beach indefinitely and do his own thing?

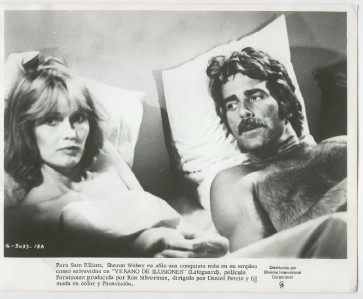

I won’t give away the exciting answer, but should warn you that it takes over 90 minutes to get to it. In the meantime, one follows the glossy, lackadaisical exploits of Rick (Sam Elliott), the title hero, a smug Burt Reynolds type who Cares About What He’s Doing and comes across as a likeable, not-too-bright all-American meatball languishing in the southern California sun. Among his many ladies are Tina (Sharon Weber), a pretty stewardess who tells him his “secret” (“You’re great technically, but you don’t feel anything”); Wendy (Kathleen Quinlan, an even prettier lovesick 17-year-old; and Cathy (Anne Archer), an old high-school sweetheart he encounters at a class reunion, now divorced and running a stylish art gallery.

The relaxed ambience throughout is so evocative of Southern California that one hardly resents the lack of a sustained plot: “I can really get into that ocean,” Rick admits at one point, which is probably the closest he ever gets to a self-definition. And director Daniel Petrie handles the proceedings as if that were the essence of his own viewpoint. If the reader can make it to a beach on his or her own steam, Lifeguard hardly seems necessary; otherwise, it offers an appropriately soporific compensation.

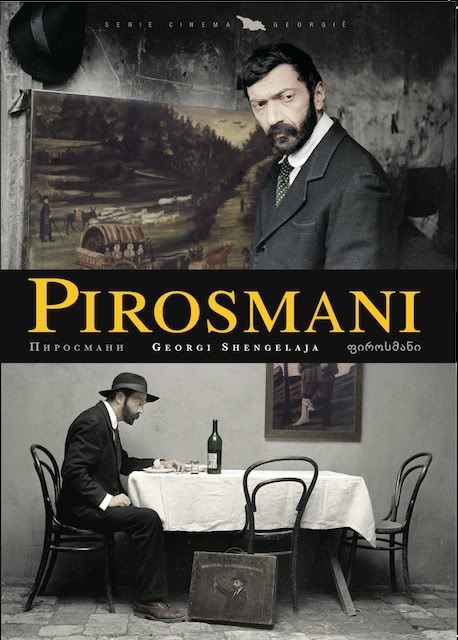

The Georgian cinema is principally known in this country through the enchanting Pirosmani, a very personal portrait of a primitive painter. Interested in discovering what else this Soviet branch of filmmaking was up to, John Gillett travelled to Georgia last year and has now organised a season of 21 features and several shorts for the National Film Theatre, starting next week.

Pirosmani, which opens the season, can be recommended without reservation. When the Leaves Fall — the only other Georgian film I’ve seen — has an appeal of its own, but by and large a much more familiar one. Describing the work and leisure of a youth who goes to work as a foreman at a winery in Thilisi, director Otar Iosseliani develops a kind of semi-plotless form which has come to seem almost obligatory in various national cinemas all over the world. It first took root in Italy under the label of Neo-realism, but equivalents have cropped up in subsequent decades in this country, North America, and virtually all of Europe.

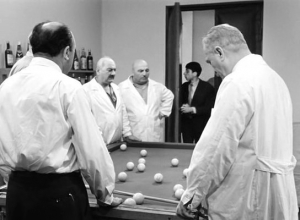

In nearly every instance, it can be described as an affectionate, unrigorous portrayal of how the working class of that country lives. In When the Leaves Fall, it largely involves the young hero’s shyness and his rebellious response to the corruption at the winery whereby bad wine is bottled even after the workers at the vat refuse to drink it themselves. Gillett makes stronger claims, one should mention, for A Singing Blackbird [see still below], a later Iosseliani feature; the latter opens the season along with Pirosmani, and anyone interested in exploring Georgian cinema could probably do no better than to start off with this double-bill.

In terms of personal favourites, there are two other films showing at the National Film Theatre which can be passionately recommended to anyone who hasn’t yet encountered them: Kenji Mizoguchi’s Sansho the Bailiff tonight, and Josef von Sternberg’s The Scarlet Empress tomorrow. Either one of them automatically knocks every film currently playing in London instantly out of sight.