From the Chicago Reader (February 15, 2002). — J.R.

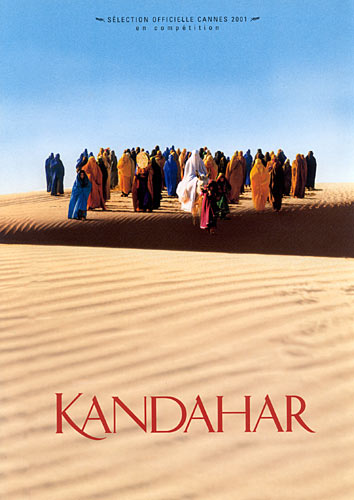

Kandahar

*** (A must-see)

Directed and written by Mohsen Makhmalbaf

With Nelofer Pazira, Hassan Tantai, and Sadou Teymouri.

“Shall I recite the Koran for the dead?”

“We are the dead; sing for us.”

— Kandahar

There are times in history when the aesthetic quality of a work of art appears to become secondary to the urgency and currency of the work’s subject matter. The era of Italian neorealism was arguably one of those times. Kandahar — a film in which the terrible and the wonderful, the gauche and the graceful, the beautiful and the ugly, and the smart and the not-so-smart rub shoulders — surely marks another.

In many ways the qualities of Kandahar that derive from actuality operate as art ordinarily does — so that, for instance, the bad acting serves as well as good acting would to bring us closer to the people we’re seeing. In some ways, the bad acting may even serve better, because it allows more of the actors’ personal characteristics to shine through. Yet once we become aware of this, our responses to the actuality become aestheticized. And even if we could overlook the quality of the acting altogether — no easy matter — writer-director Mohsen Makhmalbaf is too much of an artist to abandon the aesthetic parts of his sensibility. He’s also too much of a moralist to use his artistry to beat the viewer into submission — the way Majid Majidi does at times with his use of sentimentality, most recently (if less egregiously than usual) in Baran.

Started in 2000 in Iran near the Afghan border, shot in haphazard and difficult conditions, and completed the following year in time for the Cannes film festival in May, Kandahar has taken on a prominence unforeseen by Makhmalbaf thanks to the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan. The film has stimulated so much buzz over the past four months that I was one of the suckers who fell for the false rumor flying around last fall that George W. Bush had requested a screening of it in the White House — probably because I wanted to believe it, though I marveled at the time that it might have been the first subtitled movie he’d ever seen. The rumor has had so much staying power that it was still being repeated in the London press in early January. Clearly someone has a good press agent.

The story concerns an exiled Afghan journalist named Nafas (Nelofer Pazira) who arrives at the Iran-Afghanistan border determined to find her sister, who’s suffering under the rule of the Taliban and has threatened to kill herself in three days, at the time of a solar eclipse. As the Christian Science Monitor‘s David Sterritt has noted, the eclipse — an image of which opens and closes the film — functions as a poetic symbol for women living behind the veil. While Nafas travels cross-country by diverse means — guided first by an old man from a refugee camp, who has her pose as his fourth wife, though this makes no difference when they’re stopped by bandits, and then by a boy expelled from a religious school for not reciting a passage from the Koran correctly — burkas become part of an absurdist shell game, similar to the absurdist proliferation of artificial limbs used to replace those lost to land mines. The lost limbs aren’t absurd, but Makhmalbaf’s treatment of the amputees’ incessant demands for artificial replacements renders them so, deliberately unsettling us in the process. Nafas’s next guide and companion is a black American named Sahib, who’s acting as a lay doctor to ailing Afghans and is followed around by a one-armed man who hides under a burka. After Nafas and the amputee join a bride and part of her wedding entourage, the whole party gets stopped and searched by the Taliban.

At this point the film ends, never clarifying whether Nafas will reach her sister. This ambiguity might rhyme with the nonconclusive ending of Abbas Kiarostami’s Life and Nothing More if Kiarostami’s film weren’t so stylistically consistent; Kandahar tends to split into stylistically fragmented and truncated episodes, making the film resemble an uneven collection of poems more than a continuous narrative. Not many of the poems are cohesive, but individual lines, images, and even certain cadences in the repetitive dialogue have a poetic impact. One characteristic poem borders on the surreal: Sahib consults with a woman patient while she peeks through a hole in a curtain and her answers get relayed through her little girl.

When I first saw the film at the Toronto International Film Festival, only a few days before September 11, Afghanistan was still a far cry from being fashionable. The film was then called The Sun Behind the Moon, and its aim was clearly to draw international attention to the horrors of everyday life in Afghanistan — alerting Iran and other Middle Eastern countries as well as the West to what Makhmalbaf considered a state of crisis — yet the main attraction was Makhmalbaf himself. (When I visited him in Tehran a year ago, shortly after he’d completed the shooting, he said he found it amusing that after he shaved his mustache fans near the shoot would ask him where they could find Mr. Makhmalbaf).

One of the two giants of the Iranian new wave, along with Kiarostami, Makhmalbaf is a former fundamentalist revolutionary who’s written numerous, widely varying plays, novels, stories, and essays, and 25 feature films, 19 of which he’s directed. He’s also an autodidact, which, for better and for worse, lends a tentative as well as experimental quality to virtually all of his features and to the essays he’s been posting lately on the Makhmalbaf Film House Web site (www.makhmalbaf.com). The essays disconcertingly mix intelligence and naivete in roughly equal proportions. For instance, in his long, impassioned “Limbs of No Body: World’s Indifference to the Afghan Tragedy,” posted last June, there’s no acknowledgment that the possibility of laying pipelines across Afghanistan has been of great interest to both Russia and the U.S. (and may still be, given the oil interests of Bush’s cabinet members). Yet in an interview last October he was sharp enough to offer the following critique of Marshall McLuhan’s concept of the global village: “If indeed it were the case that the mass media has turned the world into a global village, then how could Afghanistan be so utterly forgotten over the last two decades, especially during the last ten years, and yet suddenly, after the destruction of two buildings in New York, it should re-enter the global village and become [the focus of] the top news items in the world? This exiting and entering the global village has nothing to do with the mass media and everything to do with the politics behind the mass media.”

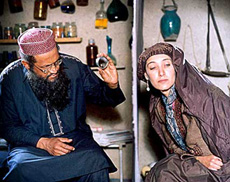

Kandahar is a departure insofar as it’s his first film in which a fair amount of English is spoken. (Coincidentally, the same is true of Kiarostami’s latest film, ABC Africa — a documentary motivated no less than Kandahar by concern about an ongoing crisis, though it keeps a clear touristic distance from the foreign culture being shown.) Makhmalbaf’s lack of ease with the language leads to an undeniable clunkiness in much of the dialogue delivery and acting of his nonprofessional cast. Yet the use of English clearly wasn’t an error from a commercial standpoint, because it makes the film more user-friendly for American audiences. Even more ironically, the most striking use of English comes from a native speaker — the American actor, identified in the cast list as Hassan Tantai, who was recently discovered by Makhmalbaf and others to be David Belfield, the man who allegedly assassinated a member of the shah’s secret police in Washington, D.C., during the Iranian revolution, escaped to Iran, and later fought the Russians in Afghanistan. (Other names he reportedly has used include Hassan Abdul Rahman and Daoud Salahuddin.)

The significance of Kandahar can be seen in the passionate debate this apparently inadvertent casting decision has stirred up — a debate that Makhmalbaf’s often unfortunate pronouncements on his Web site (“Hassan Tantai is a Che Guevara who is now being tried in Gandhi’s court”), no doubt influenced by his having been tortured by the shah’s police as a teenager, have only confused. For however one judges Belfield outside the film, his function as Sahib is mainly beneficial — partly because he’s a striking and commanding figure and partly because he appears to be enjoying the mysteries being spun around his character. To complicate our responses further, the film’s ambiguous interplay between fiction and documentary makes it impossible to know how close Belfield/Tantai is to the character he’s playing. (That his substantial gray beard proves to be fake — he calls it his burka — is especially intriguing.)

Fifteen years ago Makhmalbaf made another, and in many ways better, film in Afghanistan, The Cyclist (available on video on the Facets label); it’s more an art film with universal qualities than a piece of agitprop. Kandahar is a far more perplexing effort, insofar as it’s agitprop tinged and sometimes justified by its aesthetic qualities — some of which support the agitprop and some of which distract from it. There’s awkward and graceless dialogue, which includes some endlessly repeated exchanges that register like mantras. There’s the beautiful mix of colors and the sculptural aspect of the desert compositions. There’s the black humor of some of the situations, such as the glee with which the boy guide strips a ring from a skeleton and then tries to sell it to Nafas for $5, insisting repeatedly that the corpse is “clean,” which evokes alternately Luis Buñuel and Samuel Fuller. And there’s the almost completely disheveled narrative, which starts off as a classic picaresque adventure, gravitates toward the grotesque and anecdotal, and finally gets suspended or simply lost behind the hypnotic strains of percussive, indigenous folk music, virtually turning into a nonnarrative reflection. In spite of all the clumsiness, the fact that we start off with narrative expectations yet don’t feel unduly disappointed by the end when they aren’t met is testimony to Makhmalbaf’s power as an artist.

This overall kaleidoscopic effect offers a kind of perpetually twisting rationale that keeps forcing us to readjust our expectations. Are we responding to art or to Afghanistan? To another culture or to our own? Is a one-armed man hiding under a burka with a book and other objects an idea that belongs in a slapstick comedy à la Bob Hope or the Marx Brothers or a monstrous metaphor for an ugly reality? Or could it be both?

The issues raised by these questions turn out to be closely allied to those raised by war, and the widespread speculation that Afghanistan may not occupy American attention spans for long, especially once the war on terrorism moves to a new locale or our government announces another policy shift, only intensifies the urgency of Afghanistan’s problems, which the defeat of the Taliban in no way makes irrelevant. Thanks to the shifting tone and manner of Kandahar, we wind up responding in many different ways at once, and if the overall effect is still scattered, the burden of making sense of it all — as art and as reality — reverts to us. Considering the responsibility we’ve already assumed, that’s as it should be.