From the Chicago Reader (March 4, 1994). — J.R.

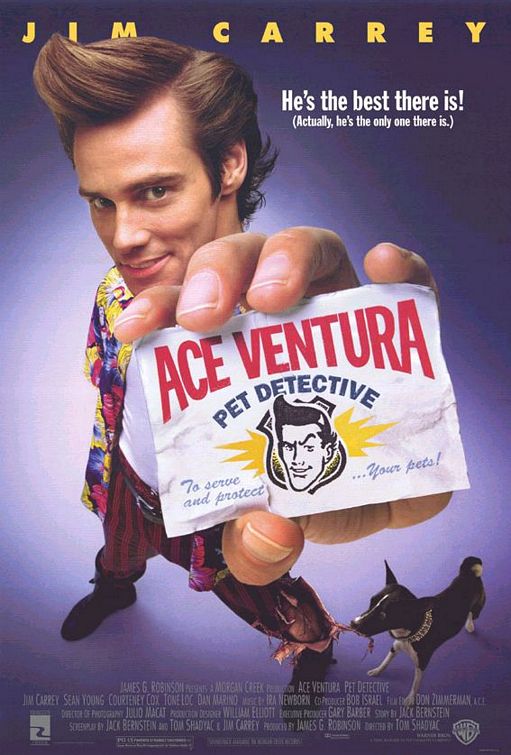

* ACE VENTURA: PET DETECTIVE

(Has redeeming facet)

Directed by Tom Shadyac

Written by Jack Bernstein, Jim Carrey, and Shadyac

With Carrey, Sean Young, Courteney Cox, Tone Loc, and Dan Marino.

Why go back to a movie that affected me the first time like a piece of chalk squeaking across a blackboard? Well, for one thing, neither I nor any other reviewer I know of came anywhere close to predicting that Ace Ventura: Pet Detective would not only find an audience but sail to the top of the box-office charts. How did we all miss the boat? “An appallingly bad movie, a certain candidate for worst of the year,” begins Gene Siskel’s capsule review in the Tribune; it concludes, “Don’t ask how this was financed.” These were my sentiments exactly at the press screening — a sort of stupefied horror at the manic leers and terminally stupid gags of star and cowriter Jim Carrey, coupled with disbelief that anyone could possibly go for them. But when the movie opened it soon became clear that at least some financiers knew exactly what they were doing. What did they understand that the rest of us grown-ups missed out on?

Turning up for an early show of this PG-13 opus at Webster Place one Friday last month, along with a fair number of others, including many preteen boys, provided me with some clues. For one thing, I saw that being grossed out was part of the game. After all, couldn’t it be argued that Jurassic Park‘s two real “money” shots, pitched at more or less the same audience, were (1) a man on a toilet getting devoured by a dinosaur, and (2) a gigantic pile of dinosaur shit? And wasn’t it part of the appeal to kids of The Simpsons, when that show premiered, that parents were less than happy about Bart? One should consider the possibility that TV has as much to do with tearing families apart as it does with binding them together — and not only because it gives everyone a good excuse not to communicate. It also helps to create distinct demographic-market targets within every home, providing different age groups with different narcissistic models. And since one of the prime products sold on TV is movies, it stands to reason that movies should divide us from one another as well — in terms of class as well as age. From this point of view, “movies for the whole family” like The Wizard of Oz are already becoming relics of our pre-TV past.

Jim Carrey is a recognizable product because Ace Ventura: Pet Detective is a spin-off of a TV show called In Living Color, which I haven’t seen. The movie differs most noticeably from TV in its raunchy humor, which often goes beyond what one would expect for a preteen audience. Ace Ventura‘s opening adventure at first seems very much in keeping with standard Saturday-matinee farce: Ace retrieves a kidnapped dog by pretending to be a delivery boy, using a cartonful of broken glass and a toy dog resembling the real one. Finally the foiled villain smashes Ventura’s car to smithereens with a baseball bat as Ace drives away with the dog. Then come the first intimations of a burlesque show: Ventura goes to collect his reward, which is a blow job (offscreen) from the dog’s owner, a woman with bulging breasts. He responds ecstatically by swinging wildly from some unseen ceiling fixture.

After this slam-bang opening, Ventura’s arrival home to a veritable Noah’s ark of pets in his run-down Miami apartment seemed not at all hyperbolic. The blow job got at least as many laughs from the Webster Place crowd as the attack with the baseball bat, but the relatively sweet and longer sequence about Ventura’s hidden menagerie — a fantasy smacking of old-fashioned Disney — was received more coolly. This is hardly surprising given the torrential self-infatuation of the hotshot hero: his identity as a principled animal lover, however necessary to the overall concept, seems distinctly pasted on.

The movie’s main event is tracking down the kidnapped mascot of the Miami Dolphins as well as the team’s star quarterback (Dan Marino, playing himself), who also gets kidnapped on the eve of the Super Bowl. Along the way Ace gets romantically involved with the team’s marketing director (Courteney Cox), whom he eventually humps four times in succession while his pets watch (again, to much appreciation from the Webster Place crowd). Among other highlights, Ace catches a bullet between his teeth, grosses everyone out — including his lover-to-be — at a party thrown by a billionaire fish collector who may be linked to the kidnapping, and finally exposes a demented transsexual criminal in a xenophobic finale that dimly recalls Beyond the Valley of the Dolls in its giddy tastelessness. The bad vibes that accumulate seem part and parcel of the hero’s narcissism, and the overall “message” recalls a friend’s description of the spirit of Milos Forman’s Hair — “Fuck you, you’re not me.”

Still, being part of a happy crowd is different from being part of a unhappy one, and even if a second viewing of Ace Ventura didn’t convert me into a fan, at least it gave me a better idea of where some of the battle lines are drawn. I even found myself laughing once, at Carrey’s mugging when his character, wearing a tutu over Bermuda shorts, is behaving like a lunatic in order to get himself admitted to an insane asylum. He impersonates a football player running in slow-motion, then prepares for an “instant replay” by reversing the whole routine, garbled speech and all — a form of VCR humor I could share.

What also got me thinking about Ace Ventura were a couple of facts that came up in the recently aired fourth part of a series devoted to Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis on the Disney Channel. First, the 1954 Martin and Lewis remake of Nothing Sacred, called Living It Up, made more money than Singin’ in the Rain, On the Waterfront, or The African Queen. Second, the 1951 Sailor Beware, the duo’s third feature and their biggest hit, a black-and-white remake of The Fleet’s In, was seen by an estimated 80 million people during its initial run. As someone who’s been a passionate Lewis fan since the age of six, when he made his first screen appearance in My Friend Irma, I’ve long been fascinated by the hostility toward him expressed by many of my contemporaries in recent years, coupled in some cases with an irrational denial that he was all that popular to begin with. Certain parallels between Lewis and Carrey — leaving aside the issue of their respective talents, they’re both aggressive, hyperbolic, and infantile — made me start speculating about how much one’s age and the correspondingly different relationship with one’s own body tend to affect one’s responses to physical comedy. Adolescents, whose bodily changes induce a perpetual feeling of awkwardness, may laugh in recognition at the same gag that to adults serves only as a reminder of their former anguish. (There are differences between Carrey and Lewis, however: Ace projects a smug narcissism closer to Lewis’s Buddy Love in The Nutty Professor — a deliberate antihero or villain in some ways resembling Martin and Lewis combined — than to the usually meek Lewis character.)

Such comics as Lewis, Pee-wee Herman, and, much earlier, Charlie Chaplin, seem to provoke in us unreasoning love, hatred, or both. Sometimes one emotion succeeds the other. Martin Scorsese in The King of Comedy included a true incident from Lewis’s life, a virtual digest of his career: Lewis’s character, a talk-show host, is walking down a midtown Manhattan street when an awed fan standing at a pay phone tries to get him to say something to a relative she has on the line. When he politely demurs, she immediately turns on him, blurting out, “You should get cancer.”

For Chaplin and Lewis, nearly universal love turned into widespread disaffection; Chaplin was hounded out of the country, then barred from reentry in 1952 by the U.S. attorney general (a move recently defended by good-guy Ronald Reagan). In the more ambiguous cases of Herman and Carrey, the love felt by children is pitted against the hatred of grown-ups. It’s worth adding that puritanical hysteria about Chaplin’s and Herman’s offscreen behavior had a lot to do with the banishment of both from their privileged places in the media.

Jim Carrey resembles Andrew Dice Clay, and Ventura resembles Clay’s character Ford Fairlane, as I note in my capsule review: so why is it that The Adventures of Ford Fairlane flopped and Ace Ventura hasn’t? The differences in response may be partly demographic, related to both age and political orientation. Both detectives are depicted as godlike superstuds, but Clay’s Fairlane seems to belong to the Rush Limbaugh camp — not exactly a preteen constituency — while Carrey’s Ventura (who seems to own as vast a collection of unbuttoned Hawaiian shirts as James Woods in Salvador) might be said to embody Oliver Stone’s idea of a macho progressive. (Imagine Limbaugh as Wyatt Earp in Tombstone: you’d have as big a box-office disaster as Ford Fairlane.)

I’m not arguing that the mainly young audience of Ace Ventura is politically minded, at least on any conscious level. But the fact remains that familiar character types on TV — most kids’ daily fare — still have plenty of political connotations and meanings in their everyday lives. Ventura, a friend of birds and animals who specializes in bathroom jokes and can’t pay the rent, is a misfit and outsider, whereas Fairlane is a spiffy dandy and thus has a closer relationship to the world of adults. Ventura’s prime weapon in the corrupt world of grown-ups is the gross-out, for which a good many preteen boys feel a special affinity.

Though I can’t claim to share this affinity — at least not when Ventura plays ventriloquist with his own asshole for what feels like an entire reel — I can still recall laughing my head off when I saw my first Luc Moullet movie in my early 30s. The film, Moullet’s first, was the 1960 short Un steack trop cuit (Overdone Steak), and a lot of it consists of the young hero grossing out his older sister with his obnoxious table manners — eating with his fingers, noisily spitting out pieces of food, sucking juice off his plate. When she asks him what time it is, he responds, “At the sound of the third belch, it’ll be exactly 7:49,” and demonstrates. But one reason I was able to laugh so guiltlessly at these puerile goings-on was the subtext of complicity and affection between the siblings, which gave the whole film a warm and poignant afterglow. The only such moments in Ace Ventura — and there are not very many of them — transpire between the pet detective and his birds and animals; other humans are conspicuously absent from this sort of spiritual bonding, and it’s not hard to understand why, given Ace’s requited self-infatuation. Moullet — who may be the most consistently neglected comic director alive — has made 21 more shorts and features since Un steack trop cuit, but has never made any inroads at all in the U.S. market, and perhaps never will. Still, it’s impossible for me to forget his shining example when I’m confronted with obnoxious comedy in its less humanistic forms.

“All right we are two nations,” wrote John Dos Passos in U.S.A., a trilogy that came out during the Depression: the two nations the novelist had in mind were different social classes. Obviously the same divisions exist today, but access to technology more and more defines the experiences of the two classes; and within each class generational differences concerning that technology may be becoming just as divisive. Earlier generations were linked primarily by wars and social movements, but a recent movie like Reality Bites suggests that the members of “Generation X” — a concept manufactured by TV — are linked only by their experience of 70s TV shows. This suggests that if you’re in that age group and you weren’t watching TV back then, poor sap, you don’t belong to any generation at all. Even worse, it suggests that wars and social movements — present and future — may be only TV shows or video games to begin with. (It’s easy to imagine that “Generation Y” will be defined by the video games they played, and “Generation Z” by their software programs.)

If Andy Warhol’s famous utopian remark — “In the future everyone will be famous for 15 minutes” — sounded pretty fanciful during the 60s, this was largely because of the faith it implied in the media’s universality. In the 90s, there’s more reason to believe that eventually most people will either live on the so-called information superhighway — permanently plugged into a computer and an interactive TV set — or be in prison, which entails only limited use of TV and still more limited use of computers. Within this universe, having no connection with TV or computers will be tantamount to not existing. In contemporary terms, that means being homeless.

Ace Ventura, who might be described as TV’s answer to Saint Francis of Assisi, offers shelter to the homeless, which given the world of children’s TV can mean only one thing — animals. Animals, after all, are permitted to live without computers or TV sets and still earn our affection because they’re our pets. But human beings without computers or TVs implicitly deserve only our scorn — the kind that Ace dishes out in gleeful abundance to fellow slum dwellers as well as to billionaires — and punishment, to be provided by our costly crime legislation.

I still don’t like this movie.