From the Autumn 1988 Sight and Sound. — J.R.

“I earn a good living and get a lot of work because of this ridiculous myth about me,” Orson Welles told Kenneth Tynan in the mid-60s. “But the price of it is that when I try to do something serious, something I care about, a great many critics don’t review that particular work, but me in general. They write their standard Welles piece. It’s either the good piece or the bad piece, but they’re both fairly standard.”

Standard Welles pieces were for once not the main bill of fare at a major Welles; retrospective and conference held last May at New York University and the Public Theater. A welcome amount of concrete research into Welles’ work in radio, theatre and film was aired, along with the obligatory theoretical exercises. Sidebars included an extensive exhibition of Welles’s radio shows and materials documenting stage productions, and an effectively staged reading of Moby Dick — Rehearsed, a prime instance of how Wellesian magic could be conjured out of suggestively minimal sounds and images.

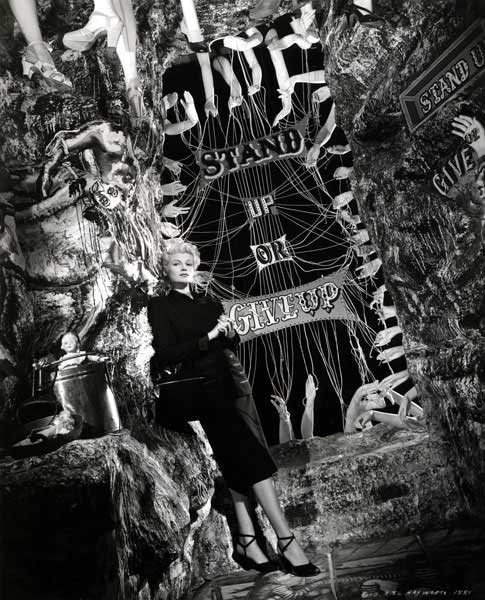

In his keynote address, James Naremore offered some fascinating glimpses into the Welles archive in Bloomington, Indiana. The original version of THE STRANGER was half an hour longer, with a flashback structure, a surreal early scene set on a dog-training farm in Argentina and a nightmarish dream sequence. Even more tantalizing was the description of the original design of THE LADY FROM SHANGHAI, based on a 1947 cutting continuity of a pre-release version that was about an hour longer. Among many finds: Michael O’Hara’s first encounter with Elsa Bannister in Central Park was depicted in a lengthy camera movement charting the separate trajectories of both characters and a cruising police car, similar to the opening shot of TOUCH OF EVIL.

Some papers concentrated on lesser-known aspects of the Welles oeuvre. William Simon, the conference organizer, focused on two wartime propaganda radio series, Hello Americans and Ceiling Unlimited, which used some of the pseudo-documentary techniques of Julius Caesar on stage, The War of the Worlds on radio, and the KANE newsreel, and anticipated such essay films as F FOR FAKE. Andrea Nouryeh gave a detailed description of the 1941 stage adaptation of Native Son, which featured the Rosebud sled among the props in the Thomas tenement flat, and had Bigger Thomas firing a gun into the audience as actors dressed as policemen proceeded to the stage from the balcony.

Perhaps the most remarkable instance of reinterpretation based on fresh information came from Robert Stam’s account of the ill-fated IT’S ALL TRUE. Drawing on an array of Hollywood and Brazilian documents, including the research conducted and commissioned by Welles; at the time, Stam persuasively argued that most of the complaints about Welles’s profligacy in Brazil can be attributed to his radical pro-black stance, including the fact that he enjoyed the company and collaboration of blacks, as well as his insistence on featuring nonwhites as the pivotal characters in both the film’s Brazilian episodes. Stam also examined how “in his interest in the northeast, in the cangaceiros (rebel bandits), in millennial cults, in popular culture and rebellion, Welles managed to anticipate many of the themes subsequently taken up by Brazilian Cinema Novo in the 60s and after.” Indeed, the Brazilian government recently voted to finance the feature about IT’S ALL TRUE that is being planned by Richard Wilson, Welles’s assistant in Brazil, including Wilson’s reconstruction of the remarkable Fortaleza episode.

The climax of the weekend was Oja Kodar’s screening of excerpts from four unfinished or unreleased films — an event that was well attended, although oddly enough not by many of the conference’s more prominent academics. There was a short scene from THE DREAMERS, already discussed in these pages (Sight and Sound, Summer 1986), and one reel of THE MERCHANT OF VENICE. This is a provocative sample — fully edited, scored, and mixed — of a finished film whose soundtrack was stolen in Rome in 1969, soon after the film was completed, for reasons that remain mysterious. (Kodar possesses the complete negative, but without sound, apart from this reel.) Featuring Welles as a heavily made-up Shylock, a spectacular array of festively decorated boats and a use of color that is distinctly different from that of THE IMMORTAL STORY (with gold predominating in the harbor), the reel is too fragmentary to constitute more than a teaser.

The three reels from THE OTHER SIDE OF THE WIND offered three complete scenes. Earlier versions of the first two were shown at Welles’s 1975 AFI Tribute, and are described in James Naremore’s The Magic World of Orson Welles. The third charts an unsettling series of exchanges between director Jake Hannaford (John Huston), surrounded by members of his entourage at his birthday party, and a prissy schoolteacher (Dan Tobin), clearly out of his depth, whose former student is the lead actor in Hannaford’s film-in-progress. Hannaford’s banter is basically macho gay-baiting, and the musically timed reverse-angles which alternate between his gibes and the teacher’s embarrassed rejoinders or giggles finally give way to simple exchanges of looks. Relentlessly prolonging and exacerbating the queasy tension, this sequence is the most aggressive employment that I know of champ contrechamp.

But the major revelation was the four reels of DON QUIXOTE. This series of fully edited but only partially dubbed black and white sequences, in no apparent order, already provides strong evidence of why Welles never wanted to let go of the film: it is so fully Welles and Cervantes at the same time, and so close to the wellsprings of his inspiration, that it must have served as his ultimate plaything. Completion would only have put an end to the game.

The materials at hand are simple and unadorned: Quixote (Francisco Reiguera) and Sancho Panza (Akim Tamiroff), both in ragtag period costume, and contemporary Spain all around them. When they pass through a town, with crowds waving, the continuing relevance of Quixote is ironically underlined by the presence of his name on shop signs and billboards, including one for Quixote Beer. The rural landscapes are worthy of Dovzhenko, with a similar dominance of sculpted sky over ground. There are no sound effects. When voices are heard, they belong exclusively to Welles — as both his characters and in one sequence as himself off screen, addressing a querulous Sancho, who speaks back to the camera.

The interplay between master and servant is perhaps most hilariously expressed in a scene on a city rooftop, where Sancho is washing his master in a trashcan next to a TV aerial, calmly soaping and scrubbing Quixote’s arms while they wildly gesticulate in the midst of nonstop pontifications. The earthiness and physicality of the characterization parallels that of Falstaff, reminding one of the paradox that Welles’s most personal work, came in literary adaptations — Tarkington, Shakespeare, Dinesen — rather than in original scripts such as KANE and ARKADIN.

Published on 15 Aug 2011 in Notes, by jrosenbaum