From the Chicago Reader (April 15, 1994). — J.R.

** SERIAL MOM

(Worth seeing)

Directed and written by John Waters

With Kathleen Turner, Sam Waterston, Ricki Lake, Matthew Lillard, Scott Wesley Morgan, Walt MacPherson, Justin Whalin, Patricia Hearst, and Suzanne Somers.

“Outside it’s hot and muggy. I buy a carton of cigarettes, ever bitter that I’m taxed so highly (11) on the one purchase that actually brings me happiness. They ought to tax yogurt (12); that’s what causes cancer. A neighbor, who always seems too familiar for her own good, passes me and makes the mistake of saying, ‘Good morning.’ ‘Shut up!’ I snap, making a mental note of her hideous tube top (13) and ridiculous Farrah Fawcett hairdo (14), so popular with fashion violators. And then I see it, a goddam ticket on my car, even though the meter (15) has only been in effect ten minutes. I have to take my rage out on someone! I run toward this fashion scofflaw as she gets into the most offensive vehicle known to man, “Le Car’ (16), and yank her door open as she frantically tries to lock it. ‘Not so fast, miss,’ I bark. ‘There’s a certain matter of this ticket you’ll have to take care of — $16 for gross and willful fashion violations!’ She gives me the finger and peels out, turning up the radio so I hear the voice of the worst-dressed man in music, Stevie Wonder (17), braying in my ears.” — John Waters, “Hatchet Piece (101 Things I Hate)” (1985)

Neither as energetic and assured as his Hairspray (1988) nor as lackluster and formulaic as his Cry-Baby (1990), John Waters’s Serial Mom alerts us to the fact that the impresario of outrage is getting older and wiser, without ever letting us forget that he still has some fight in him. Pushing 50, the bad boy from Baltimore who made his name over 20 years ago — by inducing an overweight drag queen named Divine to eat dog shit in Pink Flamingos — is actually becoming a little pensive about his shock tactics nowadays. But asking a current audience to think in a movie is probably more of a provocation than asking it to flinch or blanch, and from this point of view Serial Mom is worth 93 minutes of anyone’s time. For all its moments of uncertainty, it still has an irreducible vision to impart.

Overhearing a colleague complain, “What’s the point?” after the press screening helped to confirm this achievement in my mind. Presumably, if Waters had stuck to his drag queens and dog shit — now coin of the realm in the highly acceptable world of exploitation — the point would have been perfectly obvious. But the contemporary awe felt toward mass murderers and the everyday gravitation of petty annoyance toward murderous rage are such respected staples of present-day America that the amusement Waters finds in them, even though he recognizes them in himself, may seem like esoteric impertinence to viewers more accustomed to seeing them “seriously” honored and exploited, in popular movies ranging from The Silence of the Lambs to Schindler’s List. When Waters finds devout churchgoers who celebrate capital punishment a bit off their rockers, it is he and not the churchgoers who appears to be oddly out of step with his times.

The best word for Waters’s particular angle of vision is satire — a word you aren’t likely to find much in press packets, hence in reviews, because as George F. Kaufman once noted, that’s what closes in New Haven. You don’t hear it often in reference to The Ref, either, though that’s certainly what the crowd at the Norridge and I were laughing at when I finally caught up with that movie a couple of weekends back.

“All people look better under arrest. The ugliest sex criminal and the motliest junkie take on a special glamour as they are handcuffed and dragged before the crime-hungry American public. A new criminal is the hottest of all media stars; it’s the only kind of celebrity that can happen literally overnight. Trials are the most entertaining of all American spectacles, always better than the theater, and except for a few special cases, much more thrilling than movies.” — John Waters, Shock Value (1981)

Up until now, there have been only two kinds of John Waters features: satiric comedies with Divine (Mondo Trasho, Multiple Maniacs, Pink Flamingos, Female Trouble, Polyester, Hairspray), which are funny and life-enhancing in spite of their flaws, and satiric comedies without Divine (Desperate Living, Cry-Baby), which are grim and unpleasant in spite of their merits. Since the untimely death of Divine after Hairspray — my favorite Waters movie to date, with Female Trouble a close runner-up — Waters’s career has been at an uneasy crossroads; perhaps this helps to account for the four years of silence between Cry-Baby and Serial Mom. Without a larger-than-life protagonist to literally flesh out his conceits, he’s like a musician without an instrument — or, more precisely, a composer without a soloist — and all that Cry-Baby proved was that even an actor as talented as Johnny Depp couldn’t make up the difference.

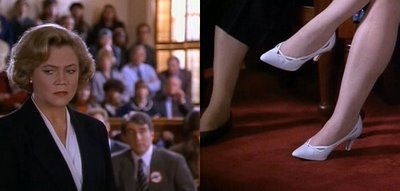

Enter Kathleen Turner as Beverly Sutphin, the serial mom — a cheerful, all-American homemaker who refuses to allow chewing gum or mention of “the brown word” (Waterese for “shit”) in her squeaky-clean household, which brims with freshly baked cookies and carefully tendered meatloaf, but who gleefully kills other suburbanites for petty crimes like impugning her son’s interest in gory movies, standing up her daughter, or failing to floss or drive with safety belts or rewind videos — and the mannerist cinema of John Waters becomes a distinct possibility again. The joy of the best earlier work is, if not exactly regained, at least plausibly repostulated. Poetry begins to glimmer once more.

“If you think about it, getting famous is easier than getting a job. And face facts, everybody wants to be famous. More than rich, more than happy, more than successful. So what are you waiting for? Quit school, forget that boring job, dismiss those nagging parents. Throw caution to the wind, get out your dark glasses, and prepare to blast off into the wonderful world of show business. Wouldn’t you rather sign an autograph than kiss a girl? Have paparazzi annoy you and your star-struck bimbo date rather than enter a mature, predictable relationship that only ends in divorce? Be an asshole instead of a role model?” — John Waters, “How to Become Famous” (1985)

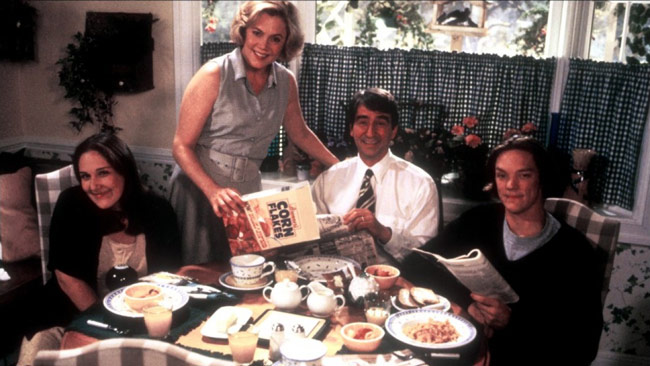

The opening title of Serial Mom informs us, “This film is based on a true story” and “No one involved in the true crimes received any financial compensation,” which starts us thinking about the meaning of both truth and financial compensation. (Waters is also a bit of a philosopher.) We’re promptly introduced to the Sutphins over breakfast — Chip (Matthew Lillard), a high school senior, is asking his dentist father (Sam Waterston) if he’s seen Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer, while Misty (Ricki Lake), a college student, is planning to bring her Pee-wee Herman doll to a flea market. A date dutifully appears on the screen (“Friday, May 19, 1993”) just as a couple of policemen appear at the front door. They’re investigating a report of an obscene phone caller in the neighborhood, someone we shortly discover (“9:37 AM” appears on-screen) to be none other than Beverly Sutphin herself. She’s getting even with a neighbor who once (as we discover in a flashback) stole her parking place.

Many more gratuitous dates and times appear on-screen over the course of this picture; sometimes their timing and occasion are pointedly parodic of police-procedural TV shows, and sometimes they seem merely arbitrary. A little later on, when Beverly is attending a PTA meeting and decides to run over one of Chip’s teachers in the parking lot after he expresses concern about her son’s “morbid interest in cheap horror films,” a pastiche of Bernard Herrmann music associated with Hitchcock movies promptly turns up in Basil Poledouris’s score. (Much later, he even offers an extended hommage to a half-hour Hitchcock-directed TV film, Lamb to the Slaughter.) In all these gags, and many comparable ones, one feels that Waters’s wit is primarily contained in his writing and only secondarily in his direction; though Kathleen Turner proves to be a godsend in giving exuberant expression to all the contradictions contained in his notion of the “serial mom,” he seldom gives the impression of having mastered the art of mise en scene. His basic talent, as I’ve tried to show in the above quotes, is as a writer, and his main gifts as a director appear to be his capacity to protect that talent and his taste in casting parts — which sort of makes him the Joseph L. Mankiewicz of sleaze. But in between the writerly gags and the star turns he seems less confident (a failing he doesn’t share with Mankiewicz), and when the humor is largely conceptual, as it is here, he seems to have some difficulty in getting from one outrage to the next.

Nevertheless, there’s an undeniable pleasure in finding a comic imagination based so exclusively on personal quirks and predilections, even when it’s less than wholly adept in telling a story. It’s fairly obvious, for instance, that Beverly’s taboo against gum in her house is inspired by Waters’s feelings of persecution as an unreconstructed smoker, just as the various clips of movies on video that we glimpse during Serial Mom are obviously things that he either loves (Blood Feast and Straitjacket) or despises (Annie) — and whether he loves or despises them is ultimately less important than the fact that he has a bee in his bonnet about them. After all, like every other Waters movie, this one is shot on location in Baltimore, his hometown — a place that he clearly cherishes and loathes in roughly equal proportions — and what gives Serial Mom all its energy is its periodic bursts of this sense of selfhood. If that makes John Waters appear old-fashioned at times, it’s a form of old-fashionedness that we should venerate and nurture, because it’s fast becoming a rare commodity.

Why? Most likely because it doesn’t “test” well. And whether Serial Mom makes it at the box office or not, what continues to make Waters irreplaceable is his refusal (or inability) to make himself anonymous. That’s what makes all his movies resemble separate editions of a privately printed newspaper; whether the separate articles are signed or not, we always know exactly where they’re coming from.