From the June 9, 2006 Chicago Reader. I can happily report that Roads of Kiarostami has appeared as an extra on the DVD of Kiarostami’s Shirin released by Cinema Guild. — J.R.

Roads of Kiarostami

*** (A must see)

Directed and written by Abbas Kiarostami

The definition of what qualifies as commercial movie fare seems to have shrunk to works that appeal to teens and preteens. Meanwhile the definition of experimental film — which traditionally has meant abstract, nonnarrative, and small-format works produced in a garret — has been expanding to address wider audiences. An ambitious DVD box set released last year, “Unseen Cinema: Early American Avant-Garde Film 1894-1941,” includes lavish Busby Berkeley production numbers and juvenilia by Orson Welles. And last year’s Onion City Experimental Film and Video Festival opened with a dazzling 35-millimeter short by Michelangelo Antonioni, Michelangelo Eye to Eye.

This year Onion City’s opening-night program reflects this tendency even more: it includes a video by cult horror director Kiyoshi Kurosawa, Peter Tscherkassky’s radical reworking of footage from The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly in 35-millimeter and ‘Scope, Andy Warhol’s two 1966 “screen tests” with Bob Dylan, and best of all Abbas Kiarostami’s half-hour Roads of Kiarostami. This video starts out as a straightforward and unassuming introduction to a selection of his black-and-white landscape photographs, but it turns into something poetic and frighteningly up-to-date that speaks to a much broader constituency.

Kiarostami, who started out in the 60s as a graphic artist, is refreshingly indifferent to his career profile as a filmmaker, though these days he has no trouble getting any of his various projects financed — Roads of Kiarostami was produced by a South Korean environmental group that puts on the Green Film Festival in Seoul. In 2003 he made Five, a collection of five nonnarrative shorts shot mainly around the Caspian Sea and somewhat misleadingly subtitled Five Long Takes Dedicated to Yasujiro Ozu. It’s been screened most often at museums, though I’m not sure they’re the best venues. It may come into its own only after it’s released on DVD, which would allow it to be seen and heard in a more relaxed environment (it’s supposed to be released later this year in Europe). The longest and most interesting segment, the last, appears to record a moonlit pond before, during, and after a storm — a false impression Kiarostami achieved only after filming several ponds over an extended period. In this respect he resembles Bela Tarr, another technical master of illusion who’s commonly misperceived as a third-world primitive.

Last year Kiarostami returned to 35-millimeter to make the middle sketch in an Italian feature called Tickets (Ermanno Olmi and Ken Loach made the other two parts), working with an Italian actress and his usual Iranian cinematographer (it can be ordered from Amazon’s UK site). Last month his exchange of “video letters” with Spanish filmmaker Victor Erice (The Spirit of the Beehive) premiered at an exhibition in Barcelona. In between, he made Roads of Kiarostami, finishing it shortly after Mahmoud Ahmadinejad started his term as president of Iran and began insisting on his country’s right to develop nuclear power plants and enrich uranium. The relevance of this is ultimately what moves the video beyond formal matters.

Kiarostami’s work in photography and film belongs to existing traditions, though he seldom acknowledges that he’s part of a community of artists, Iranian or otherwise. Yet what’s interesting about the photographs in Roads of Kiarostami isn’t their originality but what he does with them, and the same thing is true of his nonnarrative videos. After seeing Five a New York critic sneered that experimental filmmaker Michael Snow had nothing to worry about, but what fascinates Kiarostami aren’t the procedures of a structural filmmaker but the wonders of nature. His handling of photographs also echoes, superficially, Hollis Frampton’s Nostalgia, but I’m sure Frampton’s ghost realizes that Kiarostami’s interests lie elsewhere.

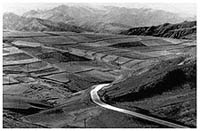

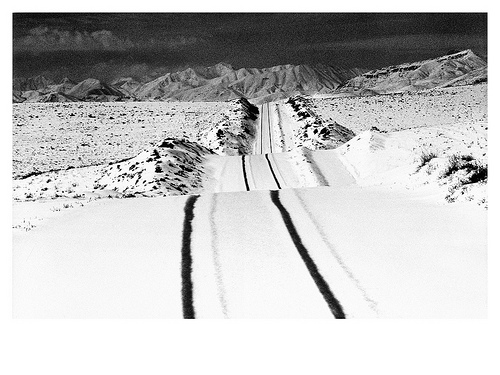

In Roads Kiarostami starts by slowly zooming in and out or panning across his photographs, making them succeed one another in overlapping dissolves, often to the strains of Vivaldi, as if to give them motion. Then he keeps his camera still while he films shots of cars moving through similar landscapes, speaking in voice-over about discovering his interest in roads and paths after realizing how many thousands of them he’d photographed. Finally he starts speaking about roads in Persian poetry and Japanese haiku and quoting examples of the former.

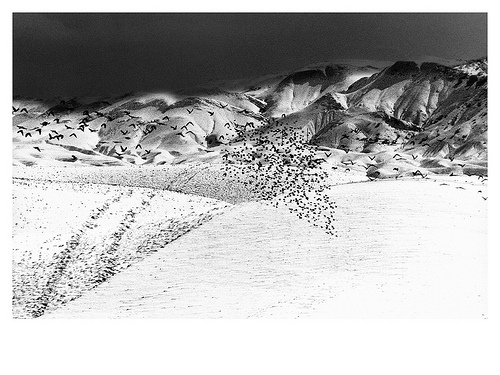

What starts out as a reverie slowly evolves into something of a narrative, with snow becoming more prominent in successive photographs, then omnipresent in a shot filmed from the front seat of a car we gradually discover Kiarostami is driving. Parking opposite a friendly dog, he ventures outside with his still camera while the video camera pans after him. The sound of crows, Japanese flute music, and a pressed camera shutter are heard, and the video camera follows the paths he and various dogs and birds take, their movements alternating with the pictures he’s presumably taking of barren trees and snowscapes. Shifting between motion and stasis, he shows a man on a horse, a scarecrow, a dog, another dog seen closer, then even closer as it faces the still camera in the last shot.

Superimposed over this still photo is the orange red blast of an atomic bomb and its mushroom cloud — the first appearance of color in the film. The photo catches fire, and the image of the dog is slowly devoured by flames. As the photo turns into ashes, a prayer from the Shiite text Nahjulbalagha appears alongside it in English: “Dear Lord, give us rain from tame, obedient clouds and not from dense and fiery clouds which summon death. Amen.”

Neither Ahmadinejad nor George Bush has been shown or mentioned, but then we aren’t being asked to think much about whose atomic bomb is falling or which fundamentalist leader is dropping it. We’re meant to remember the shock of that color and sound and the look of that dog facing us.