From the Chicago Reader (February 28, 1997). — J.R.

Three Lives and Only One Death

Rating *** A must see

Directed by Raul Ruiz

Written by Ruiz and Pascal Bonitzer

With Marcello Mastroianni, Anna Galiena, Marisa Paredes, Melvil Poupaud, Chiara Mastroianni, Arielle Dombasle, Feodor Atkine, and Lou Castel.

Lost Highway

Rating *** A must see

Directed by David Lynch

Written by Lynch and Barry Gifford

With Bill Pullman, Patricia Arquette, Balthazar Getty, Michael Massee, Robert Blake, Gary Busey, Lucy Butler, Robert Loggia, and Richard Pryor.

By coincidence, two major features by two of the most talented postsurrealist filmmakers open this week, both convoluted parables about heroes with multiple identities. Though Raul Ruiz and David Lynch are separated by a world of differences — political, cultural, national, intellectual, and temperamental — both are expanding the options in filmmaking as well as filmgoing. Each offers a different kind of roller-coaster ride that manages to be bewildering, provocative, kaleidoscopic, scary, visually intoxicating, and funny.

Ruiz — a Chilean who moved to Paris in 1974 and who makes movies all over the world (in France, Italy, Taiwan, and the U.S. in the past year alone) — has made 90-odd films and videos to date, though he’s only five years older than Lynch. (A fairly up-to-date catalog of his work can be found in the January-February issue of Film Comment. The benefits of state funding in Europe and a freedom from Hollywood budgets help explain this productivity, though it’s hard to find his counterpart even in Europe.) Three Lives and Only One Death represents a watershed, because it’s receiving the most visible U.S. release of any of his films. Conceived as a kind of concerto for the late Marcello Mastroianni, who plays four separate roles in the picture, it comprises, among other things, a wonderful summation of what the charismatic Italian maestro could do as an actor — not quite a farewell performance, because his final role (in a feature now being completed by Manoel de Oliveira) has yet to be seen, but a beautiful anthology of his turns nonetheless. This film also suggests a new stage in Ruiz’s development, for before Three Lives he wasn’t known as a director of stars, and he’s since directed Catherine Deneuve in Généalogies d’un crime, which just premiered at the Berlin film festival.

Less actor-driven than The Elephant Man, Blue Velvet, or Wild at Heart, Lynch’s Lost Highway also represents a watershed — not merely a defiant and confident comeback after five years of silence, but an audacious move away from conventional narrative and back toward the formal beauty of Eraserhead, Lynch’s first (and best) feature. By no means a meditative work in the sense that Eraserhead is, Lost Highway is defined less by visual and aural textures than by narrative flow, assaulting the viewer with a battery of effects. If Lynch hasn’t developed his themes one iota in a quarter of a century, the mastery of sound and image on display here hasn’t been seen or heard since Blue Velvet. For all its objectionable elements, Lost Highway proves that Lynch’s inflation in the media around the time of Twin Peaks — the same sort of ritualistic trial by fire that Quentin Tarantino has recently been undergoing — hasn’t altered his capacity to turn a new trick or two once the spotlight becomes less blinding.

If Lynch is essentially a painter turned filmmaker, Ruiz is fundamentally a literary man with a baroque and Wellesian eye — a man with a taste for tales and yarns rather than short stories or novels. That places him in the same ballpark as Jorge Luis Borges, who had a similar taste for English writers such as Robert Louis Stevenson and G.K. Chesterton, as well as tellers of twice-told tales like Nathaniel Hawthorne and Isak Dinesen. The first of four tales-within-a-tale in Three Lives, recounted by Mastroianni to a stranger in a cafe, is a free adaptation of Hawthorne’s “Wakefield,” the focus of a famous Borges essay about Hawthorne. It’s the account of a man who leaves his wife without cause, rents an apartment only one street away, remains there incognito for the next 20 years, then returns without explanation, long after his wife has given him up for dead, as if he’d been away for only half an hour, and is an exemplary husband for the remainder of his life. It’s characteristic of Hawthorne that he recounts this mysterious and haunting tale in strictly realistic terms. And it’s no less characteristic of Ruiz — who retains the essentials of Hawthorne’s protagonist and plot, though his setting is a Paris neighborhood — that he adds several whimsical fantasy details, all of which are illustrated visually: the nearby apartment seems to grow larger over time and contains miniature fairies who dress like Parisians and who devour the hero’s time, so that his 20 years of exile seem to pass in a single night; they gobble up his leftist newspapers, drink all his brandy, and then trap him inside a single frozen moment for two months.

The name we ordinarily give to this kind of freewheeling inventiveness is surrealism, but even though Ruiz shares certain traits with that movement (such as leftist politics), he doesn’t buy into its overall program. (“My problem with the Surrealists,” he once noted, “is that I have the suspicion that they wanted to keep you busy even while you were asleep. It’s a capitalistic problem.”) And he’s equally distant from magical realism, because he has a different relation to fiction. (“My films are not fiction films but about fiction,” he has said in an interview.)

Most radical of all is Ruiz’s denial (which he writes about at some length in his Poetics of Cinema) that all drama is based on conflict — the cornerstone, by his reckoning, of American movies (it’s certainly central to all of Lynch’s). This disagreement once led him to quit the writers’-workshop program at the University of Iowa, following the advice of one of the teachers there at the time, Kurt Vonnegut. This denial is clearly linked to his prolific output and nonstop inventiveness — if conflict is absent, just about anything becomes possible — though one could argue that it also leads at times to dramaturgical problems, including something akin to logorrhea. Three Lives and Only One Death is one of his sunniest comedies, and perhaps the most accessible, but it runs for slightly over two hours, and there are moments when it seems longer than it has to be. The prodigious invention is often exhilarating — the sheer happiness of Ruiz tossing off jokes (such as his running gag about Carlos Castaneda being a fraud), spinning yarns, devising visual tricks, and enjoying the energy of Mastroianni is infectious — but aside from a few melancholic asides and codas, his emotional palette is restricted to the same amused banter, which eventually threatens to become monotonous.

France became a kind of second home to Ruiz after he became a political exile from Chile and resettled in Paris, and Three Lives, made around the time he became a French citizen, is in some ways the most self-consciously French of his movies, despite a cast that’s made up largely of non-French actors speaking with accents. The narrator is Pierre Bellemare, a French radio broadcaster whose show served as Ruiz’s route into learning the language, and Ruiz’s recent collaborations with screenwriter Pascal Bonitzer on his scripts suggests the sort of relationship that was forged between Luis Buñuel and Jean-Claude Carrière in broaching French culture in the 60s and 70s, in features like Belle de jour, The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie, and The Phantom of Liberty — movies whose frivolous play with narrative conventions suggests another close parallel.

As an exile, Ruiz has had to reinvent himself many times in other languages and cultures, and the various characters embodied by Mastroianni in Three Lives reflect these multiple identities: a wealthy man who willingly becomes a beggar, a character who invents a family for himself, a butler who turns up with an inherited mansion and turns out to be its original owner (in another story borrowed from Hawthorne). Combining all his heroes and stories into one, Ruiz at one point turns to a Dinesen tale called “The Dreamers,” about a former opera singer with multiple identities (Orson Welles also started an adaptation of this work, the most treasured of his unrealized late projects)

This is a humanistic, relatively optimistic take on the notion of multiple personalities, predicated on the idea that we all lead different simultaneous lives. As Ruiz puts it, “Multiple personality disorder is the disease of the 21st century and is a mental, or rather, a moral disease in which one divides oneself into different compartments and builds different personalities in relation to the people one meets. You become one person when you’re with someone, and another person when you’re with someone else….I’m a virtual Balkan republic. All exiles are….You can be ten people who don’t necessarily all know each other. The idea has plenty of narrative potential.”

David Lynch’s take on multiple-personality disorder in Lost Highway is decidedly nonhumanistic and relatively pessimistic — especially in relation to character development, this being a movie fatalistically constructed like a Mobius strip. Properly speaking, this isn’t a movie with characters but with figures, each of them as overblown as a plastic inner tube. (The huge close-ups of eyes and lips that periodically blip through the narrative only add to the overall sense of abstraction.)

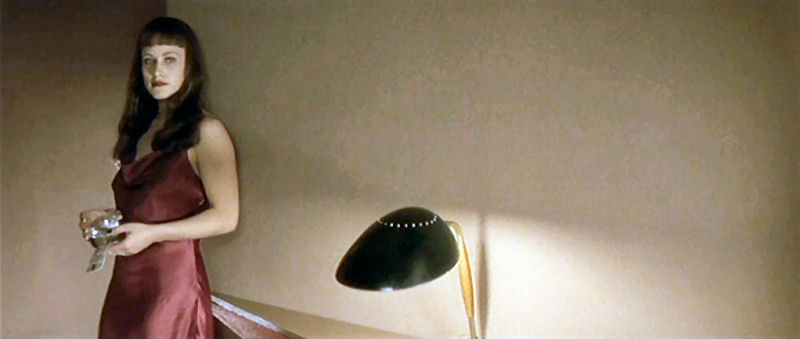

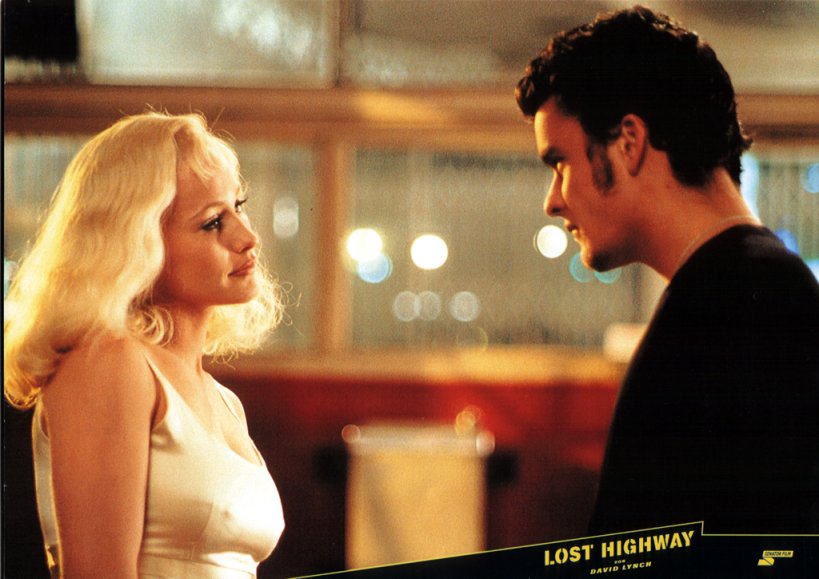

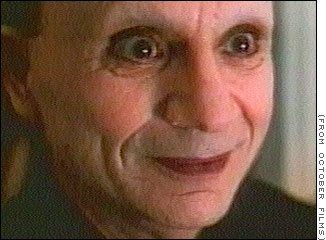

According to the logistics here, certain kinds of people are interchangeable, hence dispensable and maybe even disposable. This is true of both heroes, middle-aged and middle-class jazz musician Fred Madison (Bill Pullman) and punk garage mechanic Pete Dayton (Balthazar Getty) — the second of whom replaces the first, without explanation, in a prison cell. It’s also true of Fred’s brunette wife Renee (Patricia Arquette), whom Fred may or may not be guilty of murdering, and of a hot blond named Alice Wakefield (also Arquette), who betrays her gangster boyfriend (Robert Loggia) to have regular sex with Pete. There’s an androgynous weirdo identified in the credits as the Mystery Man, played by Robert Blake, who gives several indications that he’s Renee and Alice in another form, and even the gangster boyfriend has two identities and names, Mr. Eddy and Dick Laurent.

Similarly, a stucco Los Angeles house that figures climactically in the plot does double duty as the Lost Highway Hotel as soon as one climbs the stairs to the second floor. And cars are commonly filmed frontally, from the front or the rear, exactly as Arquette is filmed when she takes off her clothes. At one point, Pete (or is it Fred?) pistol-whips Mr. Eddy (or is it Dick Laurent?) and then stuffs him into the trunk of one of these cars, only to find him leaping out later in a fighting mood. One might wonder, under the circumstances, if the gangster is emerging from Renee/Alice’s womb — or maybe even the Mystery Man’s — in some kind of cataclysmic birth trauma.

The thrill of this kind of enigmatic rhyming structure, combined with Lynch’s masterful and often powerful fusions of sound and image, is that it makes all sorts of splashy expressionistic effects possible — moments of “pure” filmmaking in which the ideological trappings of noir become subverted by the heady mixtures (such as the literal and figurative grafting of the Mystery Man onto the body of Arquette). The limitation is that, even if the thematic preoccupations at times appear to float and circulate independent of the inner tubes, their assumptions remain mired in the adolescent mind-set (“dirty” sex and corrupted male innocence) that informs virtually all of Lynch’s features. (I’m less certain that this applies to Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me, which I’ll have to see again, but it clearly forms the affective core of Eraserhead, The Elephant Man, Dune, Blue Velvet, and Wild at Heart.)

It can be argued — and will be in a book about Lynch by Martha Nochimson that will be published next fall — that the projection of male feelings of guilt, fear, disgust, and shame about sex onto female figures in Lynch’s films is always defined as a traumatized-male construction, and that Lost Highway doesn’t have any real women. This is a plausible hypothesis, but how consistently one can read the movie in this light depends on how well one can plow through the proliferating iconography of puritanical noir clichés, which invade so much of the available space they leave little room for decoding. (Are there any real men in this movie either?)

In one way or another, all Lynch’s work seems to pivot on a male teenager’s horrified discovery of female sexuality; the celebrated closet-voyeurism scene in Blue Velvet even seems to literalize this trauma as the teenager’s discovery of sex between his parents. This is played out in Lost Highway, with Fred suspecting Renee of marital infidelity and Pete encountering Alice’s lust in conjunction with Mr. Eddy as a father figure — a transgression that implicitly ushers in guns, violence, and porn movies — but it’s also configured exclusively in terms of noir stereotypes, many of them seemingly borrowed from Kiss Me Deadly (the Robert Aldrich movie, not the Mickey Spillane novel) by way of Barry Gifford, a novelist and noir specialist who collaborated with Lynch on the Lost Highway script. (Among the many tropes with a Kiss Me Deadly pedigree are hallucinatory night shots of a highway under a speeding car, mysterious recorded messages, a central garage setting, and a beach house on stilts that explodes in flames.)

To put it simply, my problem with the noir iconography is that Lynch liberally splashes it around without any sense of historical context — a common enough procedure these days — so I can’t read it in terms of either the past or the present. (Arquette’s clothes are period noir, for instance, but the Mystery Man’s camcorder is strictly contemporary; the welcome appearance of Richard Pryor in a bit as the garage manager is offset by the fact that he seems to have been parachuted in from another movie.)

There are gains as well as losses in the absence of real characters — formally this is the gutsiest Lynch movie since Eraserhead — but the compulsive noir imagery of sexuality and corruption and the accompanying adolescent male humor ultimately become as monotonal as Ruiz’s whimsy and banter. One can tick off the showpieces designed to produce guffaws and sniggers — Mr. Eddy beating a motorist to a pulp for tailgating and not reading the driver’s manual, one-liners about shit from a duck’s ass and Pete getting “more pussy than a toilet seat.” Even if Lynch is assigning these nuggets to stock figures and deadbeats, he’s still pitching them to the peanut gallery.

I expect to remember this movie more fondly for the late Jack Nance (a Lynch axiom) expressing a preference for Fred’s free jazz on the garage radio (“I liked that”) after Pete irritatedly twists the dial to get another kind of music — a moment that rhymes oddly with Pete refusing to take a porn video from Mr. Eddy (who promises it will “give you a boner”). Both of Pete’s refusals point to the compulsive repressions of desire and self-recognition that run through Lynch’s work — starting with the literal erasures of Eraserhead — only to blossom or fester in other scenes and situations. (Fred’s free jazz blossoms earlier in the film, while a porn film occupies a large living-room screen some time later.) In the world of David Lynch, it seems, you can’t have one without the other, and the merit of Lost Highway and its rhyming structure is that they finally turn this compulsion into a structural necessity.