This piece comes from the November 19, 1993 issue of the Chicago Reader. —J.R.

A STREETCAR NAMED DESIRE

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Elia Kazan

Written by Tennessee Williams and Oscar Saul

With Vivien Leigh, Marlon Brando, Kim Hunter, and Karl Malden.

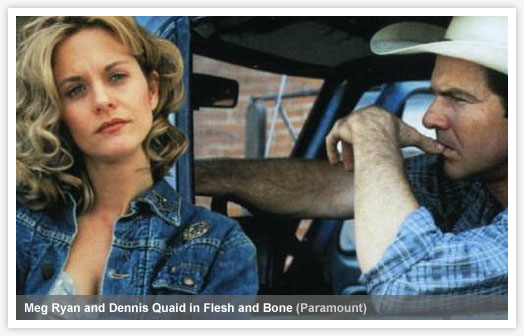

FLESH AND BONE

** (Worth seeing)

Directed and written by Steve Kloves

With Dennis Quaid, Meg Ryan, James Caan, and Gwyneth Paltrow.

Depending on whose figures you believe, the recently released “director’s cut” of A Streetcar Named Desire is either 4 percent or 8 percent longer than the version released in 1951. All the originally censored elements — lines of “racy” dialogue and shots of lustful expressions — have been restored, and the fact that this once-scandalous 126-minute movie is now accorded a PG rating indicates the progress we’ve made in some areas.

But if you think people are getting more of the movie now than they could 42 years ago, you’re mistaken. The running time is longer, but thanks to current movie-projection habits, close to 25 percent of every frame is missing at most screenings. The aspect ratio of the original movie — the relationship between the height and width of the frame — is 1:1.38, the standard ratio of all Hollywood movies in 1951. But the ratio of this movie as it was projected in Pipers Alley last weekend was 1:1.85, the standard ratio of most current movies. This means that both the top and bottom sections of every frame were masked off, with the result that the actors were frequently cut off at their foreheads, and some of the screen credits were shorn off. Such careless “censorship” of director Elia Kazan’s original compositions would be unthinkable in literature — how many of us would read Tennessee Williams’s play if the first and last lines on every page were missing? But the degradation of film images on TV has already inured most of us to such corruptions in movie theaters; if you don’t take the art of film seriously, you probably won’t mind much at all.

The same problem existed at a Jules Dassin retrospective I attended in Thessaloniki, Greece, earlier this month, the first such retrospective held anywhere. I first thought this grotesquerie was a function of the primitive projection setup, but discovered that it’s a limitation of most theaters across the globe. In Chicago, for instance, proper projection of older films can be expected at the Film Center and the Music Box, which have the proper lenses and masking equipment. But at most commercial houses the odds are that any movie made before 1953 — when ‘Scope and wide-screen ratios took over — won’t be shown correctly.

Fortunately, after some consultation with the Pipers Alley management, I’ve been assured that they will have rented the proper equipment by the time you’re reading this to ensure screenings of Streetcar in its integral form. In theory this could be done whenever exhibitors consider it worth the trouble, but given the generally cavalier attitudes about projection, I wouldn’t count on it happening very often.

Many reviewers have been calling Flesh and Bone a disappointing follow-up to writer-director Steve Kloves’s refreshing, distinctive first feature, The Fabulous Baker Boys (1989), and they’re right that the movie adds up to a rather disappointing whole. But sometimes movies register more in pieces than in wholes — not only in the sense of viewers seeing only three-quarters of Kazan’s compositions in Streetcar, but also in the sense that we often remember what we like and discard the rest. From the latter vantage point the first half of Kloves’s new movie is probably the best thing he’s done to date. Four years from now I have little doubt that this mesmerizing stretch of film will resonate in my memory far more than Michelle Pfeiffer crawling over a grand piano in Baker Boys during her torchy rendition of “Makin’ Whoopie.”

I’m mainly disregarding the rather portentous opening sequence of Flesh and Bone, in which a burglar (James Caan) implicates his young son in the murder of a father, mother, and little boy in an isolated house in west Texas. For me, the movie really starts 30 years later, with Arlis Sweeney (Dennis Quaid) — the burglar’s son — behind the wheel of his truck, still in the same region. A vending-machine supplier who travels from town to town in a kind of numb, predictable itinerary, stocking candy and soda machines, condom dispensers, and Brainy Betty chicken arcades, staying in frayed motel rooms along the way, Arlis is a kind of cracker existential hero, a blissed-out cowboy hipster caught in an endless loop of habit.

Literary narratives tend to be better than movie narratives at conveying a sense of action spread over long periods of time, perhaps because verbal grammar (such as sentences beginning “He would . . . “) usually does the job much more succinctly than most kinds of film grammar (such as slow, overlapping dissolves). But one of the more remarkable achievements of Flesh and Bone is how gracefully it conveys the long-term duration of Arlis’s compulsive, hypnotic routines without resorting to any of the usual tricks and without ever becoming monotonous.

Early on the movie settles into recording and savoring a certain poetry of southern sleaze, and Kloves has a wonderful sense of the rhythm and flavor of this seedy territory. The poetry emerges in diverse arcane details ranging from arcade chickens and “juke dimes” dyed various colors to the melted ice around beer bottles in a bathroom sink at dawn, and one also feels it in patches of the semi-hallucinatory dialogue. (Describing a woman’s drinking habits, a tired waitress says, “Put it this way — feed the girl cucumbers, it comes out pickles.”) Oddly enough, the effect is both literary and highly physical, a parade of fleeting, almost somnambulistic impressions as Arlis winds his way through his various stations; and Quaid’s portrayal of this character’s extreme isolation from everyone else — a matter of speech patterns, body language, and facial tics — is never less than masterful.

As a state of being and as a style of observation, the movie and the character are perfectly fused. But as a plot leading somewhere, Flesh and Bone stinks. Kloves has very nearly indicated as much himself: “Character is what interests me as a writer. Plot is always secondary and unfolds as a result of what’s inside a character and the activities of a character.” From this standpoint, the film’s opening sequence, which accounts for Arlis’s escape-route behavior, is nominally justifiable; but the plot that eventually grows out of it and overtakes it is simply uninteresting. I assume Kloves succumbed to this because the usual rules of commercial moviemaking — which dictate that a boring plot is better than none at all — left him no choice.

Because A Streetcar Named Desire is based on one of the greatest American plays and contains one of the greatest movie performances — Marlon Brando at his volcanic peak — it would be logical to assume that it’s one of the greatest American movies. That’s what I hoped it would look like today, but it doesn’t. For all its considerable power, it’s dated and uneven in basic ways. Most of this can’t be blamed on Kazan or Brando or Tennessee Williams, all of whom did everything they could under the circumstances, but a lot can be blamed on things that have happened in our culture since 1951.

As a job of direction, Streetcar is packed with raw energy and ingenuity, but it also represents a curious halfway house between Kazan’s stage and film work. Having been fortunate enough to have seen three of Kazan’s stage productions in the late 50s, the best of which was of a Williams play (Sweet Bird of Youth), I find it interesting to reflect on how different his strengths have been in each medium. In films ranging from Panic in the Streets to On the Waterfront to Baby Doll to Wild River, his reliance on the documentary flavor of location shooting has been crucial, yet paradoxically his theater work seems grounded in the seductive magic of artifice. Panic in the Streets — which immediately preceded Streetcar and also had a New Orleans setting — initially inspired Kazan to consider shooting Streetcar on location as well, fleshing out the stories and settings that are merely recounted or implied in the play. But after developing a script along these lines, he decided that the play was too dependent on its claustrophobic central setting — a two-room slum apartment — to survive this kind of “opening up,” and he opted for studio sets.

This perception was surely correct, and Kazan used the sets to create some powerful effects. One of them, mentioned in his autobiography, entails a gradual reduction in the physical space of the apartment to match the growing tension between Stanley Kowalski (Brando), his wife Stella (Kim Hunter), and Stella’s desperate sister Blanche (Vivien Leigh), who comes to live with them — an expressionistic effect of walls closing in that registers subliminally. But other tactics, such as the use of echo chambers and tinkly piano music to enhance some of Blanche’s dialogue about her past and suggest aural flashbacks, seem merely old-fashioned and remind us how much the ingredients stubbornly remain those of a play rather than a film. When it comes to the climactic appearance of an old Mexican lady selling flowers for the dead, the stage machinery positively creaks. Elsewhere Kazan becomes hamstrung by discrepancies between theatrical and cinematic space, so that a conversation between the two sisters in the flat being overheard by Kowalski when he’s nearly a block away stretches stage conventions past the breaking point.

Up to a point, of course, the mixture of documentary and artifice ideally suits the central dramatic tension of the play — the battle of wills between Blanche and Stanley. (“I don’t want realism, I want magic,” Blanche declares at one point.) But beyond that point, both forms of stylization now seem to teeter on the edge of campy mannerism. One of the main reasons they do is the outsize success of the movie, the indelible imprint it’s made on our culture. Given that nearly all of Brando’s and Leigh’s best actorly tricks — his simian thoughtfulness and violent gestures, her coquettish facial activity and abrupt mood swings — have been endlessly imitated and parodied by others over four decades, some lines and gestures that initially provoked gasps are now more likely to provoke titters (as they did at the screening I attended). Stanley’s brutishness and Blanche’s fluttery defenses of genteel civilization have become cartoons of actorly behavior after decades of overuse, though the fact that they can still provoke strong emotional responses in spite of this familiarity is a tribute to both actors, as well as to Williams and Kazan. (Arguably, the much less showy turns of Kim Hunter and Karl Malden can be appreciated more purely and directly today because they haven’t inspired the same imitations.)

Brando has stated that Stanley Kowalski is the only full-fledged character he’s played whom he detests. It isn’t difficult to understand the subsequent shame about and contempt for acting he’s expressed on numerous occasions, because few parts have served as more of a brute macho ideal for successive generations of males, ironically amused or otherwise. In this respect the film has moved well beyond the intentions of Williams and Kazan as well as Brando — beyond even the desire of all three to complicate the play’s emotions by making Stanley something more than a villainous lout (he’s also an honest bullshit detector and oppressed working-class Pole) and Blanche something more than an innocent victim (she’s also a snooty fake and unacknowledged bigot). Thanks to the evolving self-awareness of our culture, the work has finally and rather uncomfortably entered the realm of existing sexual politics, where the sadistic male predator and infantile rapist has decisively won the battle over the fragile and flirtatious southern magnolia before the story even starts. In this respect the movie should be seen today as an instructive embarrassment; it’s about who we are and where we’ve been as well as a galvanizing tragic melodrama that, for all its rustiness, still functions.

The cuts that have been restored to Streetcar all relate to sexual explicitness, many (if not all) of them to female sexual desire — chiefly Stella’s lustful response to Stanley even after he abuses her and Blanche and Blanche’s lustful response to a young man. There’s also a greater degree of verbal explicitness about Stanley’s climactic rape of Blanche, the act that finally drives her into terminal schizophrenia. What remains unchanged is the softened, dumb Hollywood ending that compromises the harsh force of the original play (which concludes with the resumption of Stanley’s poker game) by insisting that Stella can’t and won’t remain with Stanley.

It’s tempting to speculate about whether Stanley would have gone on to become a semiconscious national role model in the same way and to the same degree if the original film had escaped the censors in 1952. Would the franker acknowledgment of his sexual attractiveness to Stella have added to this process, or detracted from it because of the disturbing moral implications?

Sexual desire — in this case male more than female — also poses something of a problem for current tastes in Flesh and Bone. To put it simply and bluntly, part of the poetry of southern sleaze that Kloves is so adept at is a male gaze erotically focused on female flesh, betraying a sensibility that’s every bit as out of sync with contemporary notions of political correctness as Williams’s vision of Stanley as the ultimate masochistic wet dream. Part of what this male gaze picks up on are qualities that I suspect appeal to women as well as men, much as Brando’s sensuality appeals to both sexes. Meg Ryan’s sensuality is as important a part of her actorly equipment as her easy way with a Texas accent, and after seeing her transformed into a piece of cold lettuce in Sleepless in Seattle, I’m sure that viewers of both sexes can rejoice at her return to a character with carnal appetites. Women may also appreciate the deadpan neo-punk hipness of Gwyneth Paltrow’s character, though some are apt to be less appreciative of Kloves’s penchant for clothing her in the near equivalent of hot pants and for featuring a scene she has with Ryan where a fairly gratuitous reason is found for showing us her breasts. (But if Streetcar included an equivalent scene in which Brando removed his shirt in front of Malden, would anyone object, even today?)

At once complicating and enhancing this problem is an element that ultimately makes Flesh and Bone a failure as drama in spite of its attractiveness as reverie: the inability of the four major characters to interact meaningfully with one another. (In Streetcar, by contrast, all the four leads ever do is interact meaningfully; the reveries are strictly expository equivalents to flashbacks or dabs of sweaty atmosphere.) All the lead performances — Quaid as Arlis; Ryan as Kay, the unhappily married woman he meets on the road; Caan as Roy, Arlis’s father; and Paltrow as Ginnie, Roy’s kleptomaniac girlfriend, the youngest of the bunch — are satisfyingly sculpted, richly detailed, and fully rounded portraits, an impressive achievement for the actors and for Kloves. But when it comes to these characters making any kind of drama or narrative music together, the movie keeps hedging its bets or forcing certain plot issues into awkward prominence. (In retrospect this may have been a problem in The Fabulous Baker Boys as well, though the natural rapport between Jeff and Beau Bridges as brothers provided plenty of free-flowing interchanges.)

Obviously Kloves has some sense of irony about the movie’s implicit voyeurism; it’s hardly accidental that when Kay makes her first appearance, arising out of a cake for drunken cowboys to ogle, she promptly throws up, or that she wears a bra pathetically labeled Boo Boo over respective breasts, which is more likely to puzzle viewers than to simply amuse them. At the same time, the sensuality of southern life, tacky lewdness and all, gets a welcome amount of free play in this movie — as it does in a different way in Streetcar — though it’s much too serious and studied about its own quartet of characters to qualify as pornographic.

The generational differences between Roy and Arlis and between Kay and Ginnie are clearly part of what the movie’s about, and the wide-open spaces they traverse seem replicated in the emotional distances that yawn between them. (Paradoxically, it’s the oldest and least sympathetic character, Roy, who seems closest to his own emotions.) Though the movie never comes close to resonating like theater — much less the theater of a grandstander like Kazan — the overall effect is of four separate, occasionally overlapping soliloquies rather than of dynamic exchanges. That’s not a bad format for what Kloves does best, but unfortunately it has little to do with the box-office formulas that get movies financed. So eventually the implications of the opening sequence have to force their way into the picture to furnish us with a story and “development,” and the movie promptly disintegrates.