From the Chicago Reader (January 7, 1994). — J.R.

One of the funnier remarks in Variety late last year came from a Universal Pictures executive who noted that because of the special nature of Schindler’s List his company wasn’t really promoting the picture, but simply informing people it was out. I’d wager that if the other movies on my ten-best list had been given the same amount of “nonpromotion” — one of those modest multimillion-dollar campaigns — you would have heard nearly as much about them. As it happens, only about half the items on my list have had — or are having — a normal commercial run in Chicago. Still, Bitter Moon, which has so far had only one fleeting engagement here (in the fall, at the Polish film festival), is expected to have a belated U.S. release early this year, and Silverlake Life: The View From Here was aired nationally on PBS.

The limited number of Hollywood films on my list and the prominence of Chinese language ones demands some comment. It used to be a truism that American cinema excelled in unpretentious entertainment but faltered when it came to art movies, while the standard line about foreign films — meaning the foreign films Americans saw — tended toward the reverse. With rare and notable exceptions (e.g., Sunrise in 1927, Citizen Kane in 1941, Val Lewton B films in the 40s), the first truism tended to hold until younger Hollywood directors started to think of themselves as auteurs in the late 60s; it probably never was more applicable than in the 50s, when ham-fisted, issue-oriented figures like Stanley Kramer seemed to have a corner on the “Hollywood art movie.” But by the late 70s directors like Woody Allen, Michael Cimino, Francis Ford Coppola, and Martin Scorsese were elbowing their way into art movies — on the heels of auteurs like Robert Altman, Stanley Kubrick, and Arthur Penn, and later to be joined by Brian De Palma, Clint Eastwood, and Steven Spielberg — and crowding foreign art directors out of the market. It probably wasn’t coincidental that over the same period the foreign pictures being distributed here were usually simpler and less demanding than what had been shown during the 60s and 70s. Perhaps even more pertinent was the growing “necessity” that American art movies be addressed to as wide a public as possible. One of the many regrettable consequences of this development is that Hollywood art cinema now tends to operate like a closed shop: closed to influences from abroad, and thanks to its mass-market orientation, almost equally closed to innovations — in subject matter and style — from within. By contrast, contemporary Chinese-language cinema owes much of its vitality to the fact that central aspects of 20th-century Chinese history, of Taiwan and the mainland, are being examined in movies for the first time, after nearly a century of repression. It’s a cinema that in some ways is only just beginning to speak, but it’s grounded in a culture that’s many centuries older than ours and draws upon a good many things besides movies. Unlike current American cinema, which seems to draw on loads of Hollywood movies and little else. Case in point: Some of my colleagues appear to be trying to convince themselves and their readers that Schindler’s List has something new to tell us about the Holocaust, but I would argue that the film’s achievement is in simply reminding us of things we’ve forgotten. Spielberg’s filmmaking strengths are essentially conservative, and just as his use of black and white revives the cinema of the past, his view of Eastern Europe half a century ago is at best a powerful paraphrase of elements in Holocaust literature. (In no way can it be deemed any sort of advance on Simone Weil or Hannah Arendt, much less an equivalent, but if you want to be heard in the mass market you may have to claim such nonsense.)

As far as unpretentious Hollywood entertainment is concerned, it was a mediocre year. The fact that so many people enjoyed Jurassic Park and Sleepless in Seattle as if they were fresh rather than warmed-over genre romps, made me conclude that they were lucky to have seen fewer movies this year than I did. (I suspect this is an experience that generally separates professional reviewers from most other moviegoers, with quantity changing quality, altering tastes and preferences.) But as far as foreign pictures are concerned the year wasn’t at all bad, especially if you include the offerings of alternative venues like the Film Center, the Chicago International Film Festival, and Facets Multimedia. And the number of worthy American independent works was also respectably high — at least if you include videos and add Chicago Filmmakers to the list of alternative venues. Indeed, below the frosting of my top ten are plenty of respectable achievements that make up for all the dross I had to sit through in all three of the above categories. To prove my point, I’ve appended three lists of my favorites in each category that didn’t quite make it to the top ten.

1. Nouvelle vague. Contempt (1963), Ici et ailleurs (1976), Passion (1982), Nouvelle vague (1990): about once every decade, it seems, Jean-Luc Godard makes a melancholic masterpiece that synthesizes the discoveries and broods over the hard-won wisdom of his previous features. Contempt looks at commercial filmmaking, Ici et ailleurs at political honesty, and Passion at the tortured, unresolved coexistence of those two subjects. Made a little over a decade after Godard’s return to his native Switzerland, Nouvelle vague offers a bittersweet look at his own bourgeois roots and the coexistence of beauty and guilt, privilege and oppression. Filmed in a lush rural setting that’s infused with lyrical feeling and aching regret, it’s a movie that sings rather than narrates, quotes rather than recounts, and every note and word is placed with the kind of authority that comes from an artist near the summit of his powers. Undistributed in the U.S., thanks in part to a curt, violently dismissive review in the New York Times that compared the film to a perfume commercial, it was belatedly released on video in a good transfer and shown on the big screen here for the first time at the Chicago International Film Festival.

1. Nouvelle vague. Contempt (1963), Ici et ailleurs (1976), Passion (1982), Nouvelle vague (1990): about once every decade, it seems, Jean-Luc Godard makes a melancholic masterpiece that synthesizes the discoveries and broods over the hard-won wisdom of his previous features. Contempt looks at commercial filmmaking, Ici et ailleurs at political honesty, and Passion at the tortured, unresolved coexistence of those two subjects. Made a little over a decade after Godard’s return to his native Switzerland, Nouvelle vague offers a bittersweet look at his own bourgeois roots and the coexistence of beauty and guilt, privilege and oppression. Filmed in a lush rural setting that’s infused with lyrical feeling and aching regret, it’s a movie that sings rather than narrates, quotes rather than recounts, and every note and word is placed with the kind of authority that comes from an artist near the summit of his powers. Undistributed in the U.S., thanks in part to a curt, violently dismissive review in the New York Times that compared the film to a perfume commercial, it was belatedly released on video in a good transfer and shown on the big screen here for the first time at the Chicago International Film Festival.

2. The Puppet Master. Not necessarily the greatest Hou Hsiao-hsien film, but a masterpiece by the greatest Taiwanese filmmaker that adds certain registers to his already accomplished art, proving in effect that documentary can coexist with fiction — and landscape art and theater with domestic melodrama — with no loss in formal rigor or historical density. Octogenarian puppet master Li Tien-lu recounts various stages in his life between his early childhood and the end of World War II, over several decades of Japanese occupation, in the same settings where Hou imagines these events happening, and Li’s puppets and stage performances make their own contributions to the story. The austerity of Hou’s long-take, distant-camera style has deprived him of a wide audience outside Asia, and none of his features has acquired distribution in this country. But the Film Center’s extraordinary ongoing commitment to Asian cinema has done a great deal to make up the difference.

3. A tie between two Chantal Akerman films, as different from each other as two movies by the same filmmaker can be: Night and Day and From the East. The first, which showed at the Music Box last spring and is scheduled to return as a weekend midnight attraction at the Village, is Akerman at her most commercial and accessible. Alas, this still isn’t accessible enough for some people, though for me it’s the closest she’s come, after a couple tries, to capturing the lyricism and emotions of a musical. A tale of young lovers in Paris that qualifies in some ways as her Jules and Jim, the film beautifully captures the sensual feeling of summer nights in Paris. From the East — a documentary without commentary about an extended trip through Eastern Europe and Russia, most of it filmed in Moscow, that showed at the Chicago festival — is Akerman at her most austere and difficult. (It rattled one of my local colleagues so much that he erroneously reported it was filmed in black and white.) Its powerful painterly qualities, including its color, have a lot to do with what makes it so memorable: I still live with its sorrowful images of snow-filled streets and a crowded terminal, and expect these and other poignant images of the postcommunist world to remain with me for many years.

4. Schindler’s List. This is Hollywood filmmaking of a high order — masterful as story telling and extremely moving in its account of how one well-placed and exceptional Nazi found a way to save the lives of more than 1,000 Jews. In the process of conveying a lot of information about the everyday operations of “ethnic cleansing” in Poland half a century ago, Spielberg’s epic shows more tact and restraint than his previous movies, and thanks to Janusz Kaminski’s exquisite black-and-white cinematography it shows more visual taste as well. This has led some reviewers to indulge in hyperbole that might have seemed excessive even if Spielberg had saved all these lives himself rather than found a new way to make money off the Holocaust — much as Schindler himself did during the early years of the war in Krakow. (Every other Hanukkah, it seems, just as the studios are wheeling out their heaviest Oscar bids, New York magazine’s David Denby has a blinding religious illumination affording him an inside track to the Film Critic Upstairs. “Even God would be frightened by this movie,” he said of JFK. Of this movie he says, “Spielberg has converted rather than jettisoned his instincts as an entertainer — it’s as if he understood for the first time why God gave him such extraordinary skills.”) Schindler, of course, ultimately spent all his money saving Jews, and while I wouldn’t ask or expect a multimillionaire like Spielberg to do anything for anyone, I wish a little more of the credit for this picture went to Schindler himself — not to mention Thomas Keneally’s novel and Steven Zaillian’s script. At best this is an effective crowd-pleaser that scrimps on some of the complexity of its central figure for the sake of Spielberg’s usual brand of patriarchal comfort. But it still gives one more to think about than any other Spielberg feature, and it’s better directed besides.

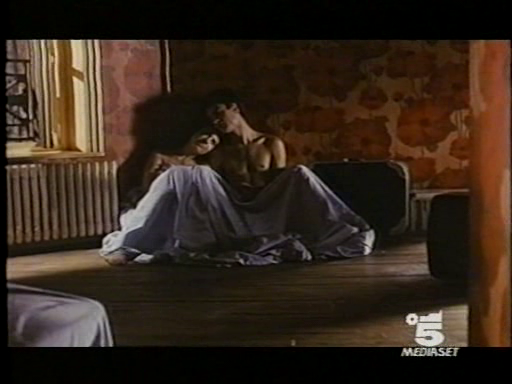

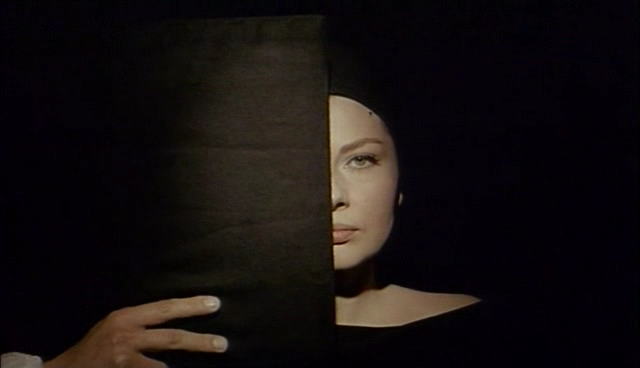

5. Bitter Moon. Roman Polanski is a Jew from Krakow who reportedly survived not because of Schindler but because his mother literally threw him off the truck that was taking them both to Auschwitz. This doesn’t necessarily explain anything, but it may provide some context for the sadomasochism and cruelty that characterize most of his films. Twice in his career he’s made brilliant confessional films about his sexual obsessions that most critics have mercilessly attacked; both, interestingly enough, are structured around complex patterns of repetitions, of themes and variations. The first, What? (1973), is such a film maudit that it no longer exists in this country apart from a truncated, crudely recut version known as Diary of Forbidden Dreams that’s distributed as a porn item. The second and better film, Bitter Moon (1992) — less comic and more disturbing — has opened to mainly bad reviews in Europe and is scheduled for a U.S. release later this year. I’m not alone among my U.S. colleagues in finding it extraordinary, but I feel almost as alienated from those partisans who find it hysterically funny as I do from its detractors. While it’s certainly full of corrosive black humor (as is the more formalist, abstract, and misogynist What?), it’s most impressive and shocking as a ferocious autocritique. The story — recounted on a luxury liner via flashbacks — concerns the doomed, tortured relationship between a failed American writer (Peter Coyote) and his French wife (Emmanuelle Seigner), as recounted to an uptight Englishman (Hugh Grant), a rather cruel stand-in for the film viewer, and his English wife (Kristin Scott-Thomas). For my money, it’s better than anything in the Polanski oeuvre since Chinatown.

6. The Story of Qiu Ju. This is Zhang Yimou’s most satisfying movie to date — even if the Chinese censors happen to agree with me. A satirical comedy about Chinese bureaucracy, it combines a fascinating look at everyday village, town, and city street life (much of it captured by hidden cameras) with the compositional and pictorial beauty of Zhang’s earlier features. Because this beauty is less obviously displayed here than in Red Sorghum, Ju Dou, and Raise the Red Lantern and has more to do with peasants than with wealthy characters, there was a widespread assumption in this country that Zhang was forsaking art for content. But I would argue that for once his aestheticism and his story telling are perfectly integrated. And Gong Li, his perpetual leading lady, is as impressive as ever.

7. Another tie, between the two best experimental works I saw all year, both of them videos: Bill Viola’s The Passing and the first two parts of Jean-Luc Godard’s Histoire(s) du cinema. The first, a beautiful black-and-white video made in 1991, is a highly pleasurable meditation on encounters between settings in the American southwest and images and rhythms relating to dreams and sleep; it premiered at Chicago Filmmakers in late June. Godard’s multilayered meditation on cinema and the 20th century as perceived through each other, which showed at the Film Center in July, is rather more abstruse, though no less rewarding after repeated viewings; it qualifies as Godard’s Finnegans Wake, full of babbled profundities and obscure poetic fusions that can be taken straight or endlessly decoded.

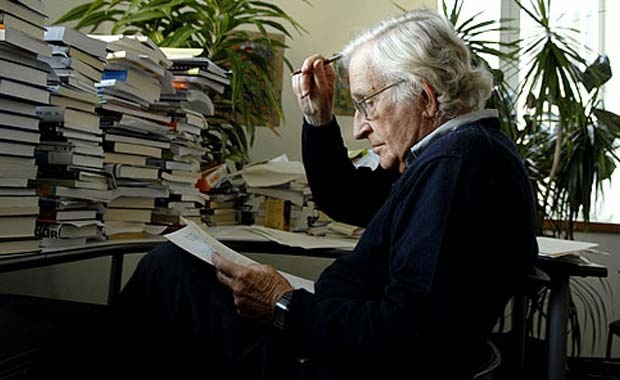

8. A tie between the two best documentaries I saw, apart from Akerman’s — both collectively made studies of widely misunderstood mavericks, many of whose works have been marginalized or buried by the mainstream: Mark Achbar and Peter Wintonick’s Manufacturing Consent: Noam Chomsky and the Media and Richard Wilson, Myron Meisel, and Bill Krohn’s It’s All True: Based on an Unfinished Film by Orson Welles. (Both films did better in Chicago than anticipated.)

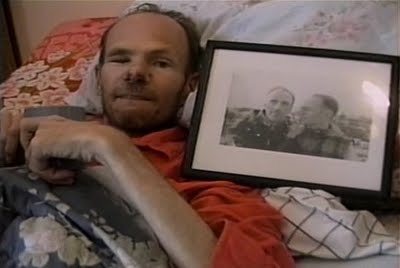

9. Another documentary, also shot on video: Tom Joslin and Peter Friedman’s Silverlake Life: The View From Here, a video diary transferred to film chronicling the death of Joslin, who had AIDS, and his relationship with his lover, Mark Massi, who also had AIDS. The work was started by Joslin, continued in part by Massi after Joslin became too ill to handle the camera, and completed (by prior agreement) by Joslin’s friend and former student Friedman five months after Joslin’s death. For all its good intentions in broaching the subject of AIDS for a mainstream audience, Jonathan Demme’s forthcoming Philadelphia seems unnecessarily timid when compared to this powerful work. The problem, ultimately, is that Philadelphia lavishes its feelings on cardboard figures, gays and homophobes alike, while Silverlake Life‘s very real characters and their mutual love burn into the heart and brain, leaving no room for Oscar-ready performances or stylistic pirouettes. I hasten to add that both Philadelphia and Silverlake Life have the same noble and irreducible aim: to make the AIDS crisis real and human and to treat its victims with love and respect. But it’s surely no insult to Tom Hanks or Demme to say that the real version carries a lot more truth and conviction.

10. Still another tie, this one between two ambitious, accomplished Chinese features: Chen Kaige’s Farewell My Concubine and Tian Zhuangzhuang’s The Blue Kite. The first is an epic based on a Chinese bestseller about two Peking Opera actors (Leslie Cheung and Zhang Fengyi) and a former prostitute (Gong Li) over half a century of troubled Chinese history (1925-1977); its style and its treatment of that history were adeptly described by Fred Camper in these pages. Shown here and, after some resistance from the censors, in China, it’s the first Chinese blockbuster to reach a wide international audience. By contrast, The Blue Kite — a semiautobiographical look by the talented director of The Horse Thief at one Chinese boy’s experiences during the upheavals of the 50s and 60s and through his mother’s three marriages — has been released neither in this country nor in China, though it did show at the Chicago Film Festival. (The standards of “commercial correctness” in this country and the standards of political correctness in China are sometimes roughly equivalent — though it’s worth noting that the Chinese public wound up seeing more of Farewell My Concubine than we did, thanks to Miramax’s recutting.) When The Blue Kite was nearing completion in 1991 it was screened for several Chinese officials, who found its political leanings so questionable they ordered all postproduction work halted, and the film was completed only through the efforts of other producers outside mainland China. The film’s powerful look at how political changes in China have profoundly affected individual lives — a theme it shares with The Puppet Master and Farewell My Concubine, but pursues even more explicitly and intimately — is stylistically more conventional than Tian’s The Horse Thief. But as a moving and complex drama, it surpassed any new fiction film I saw about Americans in 1993, including the Chinese Americans in The Joy Luck Club, for all that picture’s virtues. Given the successes of The Story of Qiu Ju, Farewell My Concubine, and The Joy Luck Club in 1993, there’s reason to believe that many Americans are beginning to discover that the lives of Chinese and Chinese Americans are as interesting as anyone else’s. Let’s hope this discovery will lead to pictures like The Puppet Master and The Blue Kite getting some form of U.S. distribution.

The ten best Hollywood films not listed above: 1. Searching for Bobby Fischer. 2. Matinee. 3. Lorenzo’s Oil. 4. The Age of Innocence. 5. King of the Hill. 6. Groundhog Day. 7. Six Degrees of Separation. 8. A Perfect World. 9. Short Cuts. 10. House of Cards.

The ten best foreign films not listed above: 1. Preface (Italy), a stunning half-hour short by Michelangelo Antonioni. Made in 1965 for a nevercompleted sketch feature, and, to the best of my knowledge, unseen in Chicago prior to the Film Center’s indispensable Antonioni retrospective, it registers like a fragrant summary of the director’s work at its most poetically mysterious. 2. A tie between two lovely French films by Agnes Varda, both about her late husband Jacques Demy: The Young Girls Turn 25, shown at the Chicago Film Festival, and Jacquot, shown at the Music Box. 3-6. Terence Davies’s The Long Day Closes (England), Jane Campion’s The Piano (Australia), Maurice Pialat’s Van Gogh (France), and Mike Leigh’s Naked (England) — all four arguably steps down for their respective directors, but all reminders of how great they still can be. 7. Gianni Amelio’s Il ladro di bambini (Italy), a sweetly observed and nicely acted character study with neorealist trimmings. . A tie between two smart archival documentaries: Peter Delpeut’s Lyrical Nitrate (Holland) and Ron Mann’s Twist (Canada). (Canadian films aren’t usually referred to as foreign, but it’s imperialist to call them American.) 9. Jean-Charles Tacchella’s Traveling Avant (France), a winsome 1987 look at fanatical French cinephilia almost 40 years earlier, prior to the New Wave, shown at Facets Multimedia. 10. Derek Jarman’s Wittgenstein (England), my kind of philosophical and minimalist biopic, shown at the Chicago gay and lesbian festival and eventually due back for a commercial run.

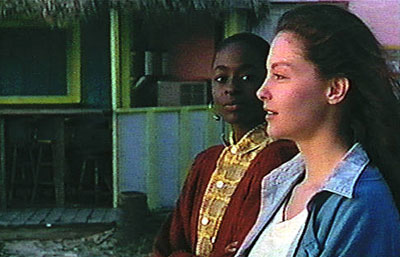

The ten best American independent films not listed above: 1. Ruby in Paradise, by Victor Nunez. 2. Poverties (an experimental short film by Chicagoan Laurie Dunphy about the homeless). 3. Arnold Glassman, Todd McCarthy, and Stuart Samuels’s Visions of Light: The Art of Cinematography. 4. Sure Fire (Jon Jost at his most caustic and pessimistic watching the American Dream crumble). 5. Alexandre Rockwell’s In the Soup (above all for Seymour Cassel’s charismatic, goofy performance). 6. Delivered Vacant (Nora Jacobson’s exemplary documentary about the gentrification of Hoboken). 7. Brother’s Keeper (Joe Berlinger and Bruce Sinofsky’s documentary about a highly unconventional small-town murder trial). 8. Boy (a nine-minute gem in the sketch film How Are the Kids? by the most underrated living American director, Jerry Lewis, his first film in a decade). 9. A tie between Dan Bessie’s Turnabout: The Story of the Yale Puppeteers (shown at the Chicago gay and lesbian festival) and Julia Reichert’s Emma and Elvis (shown at Facets Multimedia). 10. A tie between American Fabulous (directed by Reno Dakota and starring the late Jeffrey Strouth) and Robert Rodriguez’s El mariachi (a pungent allegory about independent filmmaking, widely misread as a simple genre exercise).

My annual F.W. Murnau award, given each year to the film or films that did the most to alter my sense of film history, goes to Luis Bunuel’s The Young One (1960), which enjoyed a week’s run at Facets Multimedia in a new print in October. Made with an American producer, an American screenwriter, and (mainly) American actors during the height of the civil rights movement, this neglected, politically incorrect, and highly sensuous comic masterpiece about race, sex, and nature has rarely received its due, either as a part of Bunuel’s work or as a response to American culture during this period. Seeing it again illuminated my sense of both.