This essay was written for That Magic Moment: 1968 Und Das Kino Eine Filmschau, a film program and publication organized by the Viennale and Stadtkino in late May and early June, 1998. Like some of the other pieces reproduced on this site as featured texts, this has various passages that have been recycled elsewhere in my work — in this case, both in the Chicago Reader and in my book Movie Wars — but it still seems worth reprinting, chiefly for its personal reflections on film history and, more generally, the 60s. — J.R.

My Filmgoing in 1968: An Exploration

by Jonathan Rosenbaum

In 1968, the year I turned 25, I bought my first appointment book — or at least the first appointment book that I’ve bothered to save, and I’ve saved all 30 of the appointment books that I’ve bought and filled since then. For the most part, I use these appointment books to list appointments of various kinds: meetings with friends, planned trips to other cities and countries, classes I plan to teach or lectures I plan to attend or deliver. But most of the entries concern films I plan to see and when or where they’re playing. If I don’t make it to the film, I cross out the title afterwards; if I manage to see it, I leave the entry in so it remains as a record of what I saw.

Last weekend, at age 55, I returned to my home town, Florence, Alabama, where I lived for the first 16 years of my life. It was my first time back in seven years, the longest stretch of time I’ve ever been away, and the main discovery I made about Florence is that it isn’t home anymore. It’s still many other things — probably even more things than my present home, Chicago, is — but none of those things add up to “home”.

Now that I want to return to 1968, and to the films I saw that year, I’d like to discover whether this year and those films can still be regarded as home; and if so, why.

***

1968 was a pivotal year for me, in terms of vocation as well as place. I started the year as a graduate student in English and American literature at the State University of New York at Stony Brook, in Long Island, dodging the draft and planning to become an academic; I ended it as someone planning to become a freelance writer and editor — which I became a few months later, in 1969, when I left graduate school, completed an anthology of film criticism I was editing (which was never published), and moved to Paris. (By 1969 I was able to escape the draft when I quit graduate school because the number of enlistments from Alabama was so high; but in 1968, my uncle in Alabama, who was on the draft board, advised me that at 25 I would still be called up for service if I dropped out.)

In the middle of 1968, I already spent almost three months in Paris — arriving in June around the same time the police were taking back the Odéon from the students, working on my second (unpublished) novel two blocks away at Hotel Stella on rue Monsieur le Prince, and seeing 64 films before I returned to New York.

I started making entries in my 1968 appointment book on January 15, and I’m certain that I didn’t list every single film I saw after that date. (Why? Because I know I went to see Barbarella in New York on the evening of October 21, the first time I ever took LSD, but I didn’t bother to record that title.) But including the films I saw on television, many of which I noted, I can be sure that I saw at least 190 films that year.

No less than 28 of the screenings I attended were of films by — or partially by — Godard. Broadly speaking, during that year I shifted my attention from studying literature to studying cinema, and Godard, in effect, was serving as my thesis advisor, because many of the other films I saw were ones that his films alluded to, directly or indirectly. (The two factors that allowed me to see so many Godard films in 1968, and many of them several times, was a retrospective of his work at the Museum of Modern Art in the winter that included his early shorts and a full summer in Paris; otherwise it would have been impossible.) The literature thesis I had proposed the previous year involved detailed comparisons between novels and films, including my favorite film at the time, Sunrise, and after a friend had hired me to edit an anthology of film criticism, the one article for the collection that I undertook to write myself was about Murnau’s masterpiece. Meanwhile I was trying to brush up on directors like Howard Hawks and Nicholas Ray who had been regarded in the United States as artistic nonentities throughout my teens, and an important part of the lure of Paris for me in those days was the opportunity to pursue this kind of education in optimal circumstances and more global terms: “the French,” after all, were the ones who liked Sunrise as much as I did.

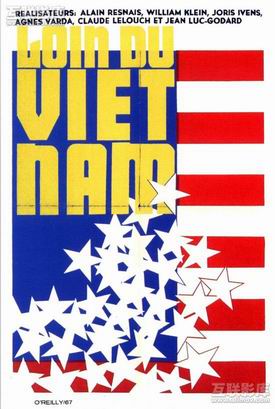

One great advantage of still having my 1968 appointment book is that it keeps me honest — especially in relation to all the deceitful accoutrements and assumptions of 1998 film culture, some of which I would also like to discuss here. Browsing through the Viennale’s program of 50 features and short films from that era, I can easily imagine that I must have seen close to half of these films during that year. In fact, I do have some recollection of seeing precisely half of these films at one time or another: 20 features and five short films (not counting, of course, the many short films I may have seen in the 60s and early 70s whose titles I no longer remember). But the hard truth is that, according to my appointment book, and in spite of all my filmgoing, I saw only six features from this list in 1968, all of them important experiences: La chinoise, Chronik der Anna Magdalena Bach, Loin de Vietnam, Partner, Petulia, and Playtime.

Why this shocking discrepancy? I can think of several reasons, all of which mitigate against the distorting lenses of nostalgia when my contemporaries and I try to remember what it was like in 1968. First of all, apart from large commercial releases, very few of which figure on the Viennale’s list, the date of a film’s completion and the date of its first commercial screenings seldom correspond; then and now, months or years have to pass before one can see a “new” film in theaters. In other words, only a few of the films on the list showed in New York in 1968 when I was around; and many of those that doubtless showed in Paris during the summer were ones that I knew nothing about at the time.

Secondly, the process by which one hears about new work — via reviews, articles, prizes, word of mouth, and so on — often takes even longer. My main critical guide about what was important in cinema in 1968 was probably Sight and Sound, which came out four times a year, and in the summer issue I read Richard Roud’s favorable article about Straub’s film, which I was to see eventually in the fall at the New York Film Festival. (Unfortunately, Roud’s piece was titled “Minimal Cinema,” fostering a misreading of Straub and Huillet’s work that was to persist for many years. But the same issue carried Tom Milne’s review of Mouchette, a film I had already seen during a weekend in Toronto back in March, and Milne’s respectful ambivalence about the film in relation to Au hasard Balthazar had done much to instruct my own.) Film Culture had been a valuable resource for most of the 60s, but by 1968 it was coming out more infrequently and devoting most of its pages to avant-garde filmmakers I had not yet investigated, including Warhol. (On the other hand, I was regularly attending silent films at Jonas Mekas’s screening facility — then known as the Cinematheque, later to be redubbed Anthology Film Archives at different locations — and lectures about them by Ken Kelman, one of Film Culture‘s house critics: Caligari, Nanook, Nosferatu, Foolish Wives, and Der Letzte Mann — the latter a film I subsequently showed in my freshman English course.) I read Cahiers du Cinema in English — 12 issues of which appeared in the mid-1960s, the last in December 1967 — but this occasional magazine translated articles that appeared in French months or years earlier, and the original Cahiers du Cinéma, which I also read intermittently and with difficulty in both Paris and New York, as well as Positif, which I read only in Paris, were resources that I was still struggling to master. Outside the ghetto of film magazines, there were encouraging signs that the U.S. literary establishment was beginning to loosen up: Susan Sontag published a lengthy defense of Godard in Partisan Review, which had already printed Richard Poirier’s “Learning from the Beatles” the previous year, leading me to hope that the New York Review of Books and similar publications would eventually become movie-literate and capable of coping with pop culture — something, alas, that never really happened. As for weekly publications, there were Andrew Sarris, Jonas Mekas, and a few others in The Village Voice but very little else that one could rely on, and the New York newspaper reviewers were only marginally helpful.

Thirdly — a more subtle yet substantially more decisive factor in this process — is the operations of culture itself, which functioned very differently in 1968 from the way they function today. What it meant to be 25 in New York and Paris in 1968 and what it might mean today are so radically divergent as conditions and premises that it seems to me impossible to consider what the differences in cinema might be without first considering this wider context.

During the 20s, 30s, 40s, and 50s, people in the Western Hemisphere went to movies the way they watch television today — not looking for masterpieces or special events but as something to do, as an everyday and unexceptional activity. Some remaining flickers of this attitude spilled over into the 60s, when, among the routine fare that was being offered, signs of a certain renewal and reinvigoration in movies were also present. Most of these signs came from exciting new features from abroad that were mainly matters of contention and debate and that received a minimum of support in the mainstream press. None of this mattered very much if you lived in a large city stocked with independent art houses and revival houses (by the late 60s there were over 1000 in the U.S.), not to mention film archives and film societies. But a decade later, once video came along — along with a refusal to enforce the antitrust laws that started during Ronald Reagan’s first term in the early 80s and that made the survival of most independent theaters impossible — going to the movies was no longer an ordinary event but something that had to be special in order to survive as a commercial enterprise. Eventually a new requirement was placed on every new feature: it had to be “hot,” it had to draw an audience the weekend it opened, and in most cases it required millions of dollars in advertising if anyone would hear enough about it to think of going. By the same token, critics became tipsters more than historians or commentators; it was now their job to tell you whether it was worth hiring a babysitter or traveling 20 miles to see a movie that was instantly recognizable as a masterpiece.

In the April 6, 1998 issue of The New Yorker is an article by David Denby, “Mourning the Movies,” that epitomizes the contemporary refusal to deal coherently or comprehensively — that is, historically or politically — with most of this changing context apart from advertising, a subject that Denby addresses in detail. Otherwise he assumes a basic continuity between 60s and 90s filmgoing and essentially blames the audience and the presumed overall state of world cinema for any differences. This is far from being the only recent mainstream example of laments about the death of cinema and cinephilia in America that refer back with yearning to the “golden age” of the 1960s and 1970s; others have appeared over the past few years by Susan Sontag in the New York Times, James Wolcott in Vanity Fair, and David Thomson in Esquire, but Denby’s attitudes are virtually identical with theirs when it comes to eliding some of the key economic and cultural determinants of our present condition. One representative quotation should suffice:

It is perhaps too late to lament the disappearance of the foreign film from a major place in our culture. After many depressing conversations, I have found that younger moviegoers, reared on little but American movies, imagine that mourners for the foreign cinema are talking about some fool’s paradise of zinc counters and cappuccino, a pretentious refuge for bearded losers and solemn girls in black. “Cineastes” — isn’t that what they used to call them? It is worse than useless to tell such moviegoers that Bergman and Kurosawa, Antonioni and Fellini, Godard and Truffaut–to name just the most obvious figures — defined our moods in late adolescence, enlarged our sense of romance and freedom and passionate melancholy as well as the expressive possibilities of movies, and that their influence was so pervasive that Bonnie and Clyde as well as the careers of Woody Allen, Paul Mazursky, Robert Altman, and a host of other American directors would not have been possible without them. […]

One must quickly add that the current French, Italian, German, and Japanese cinemas are but a remnant of their former selves, and that the new movies from China, Russia, Finland, and Iran, however fascinating, cannot replace the old masterworks in excitement and glamor. “Where are the great foreign films now?” a friend asks, by which he means that he refuses to feel guilty about not going when there are no masterpieces to see. He has a point, but even when a good French movie opens here (like Claude Chabrol’s La Cérémonie in 1996), it’s hard to scare up much of an audience for it.

Turn next to Denby’s dismissive review of Taste of Cherry — the first film of Abbas Kiarostami that he has bothered to see — which appeared in New York magazine the same day as the above essay, and you find him writing, “I can’t help thinking that the comparisons [of Kiarostami] to De Sica and Satyajit Ray and other masters betray a degree of critical desperation. Is this movie rich enough — does it show the many-sided vitality of the great movies of the past — to warrant the extravagant praise? Or are critics, depressed by the obvious aesthetic poverty of the world cinema, arguing themselves into it, placing their bets on Kiarostami because they have no other cards to play?…This is a movie of great interest — an original work — but it lacks the courage, the surprise, the ravenous hunger for life, of a serious work of movie art.” I hasten to add that two recent and unproblematically “serious” works of movie art, according to Denby, are Pulp Fiction and L.A. Confidential.

In other words, it’s business as usual: Look up the New York reviews of films by Antonioni, Bergman, Fellini, Godard, Kurosawa, and Truffaut when they opened in the 60s and you can be sure that most of them are carbon copies of Denby’s review of Taste of Cherry, showing just as much skepticism and just as little enthusiasm. How could it be otherwise, when “new” masterpieces are obliged by definition to evoke and even conform to old ones? If you’re looking for a “remnant” of former French cinema in, say, Irma Vep — a film that Denby incidentally likes because for him it exposes the bankruptcy of contemporary French cinema — then the very idea of a French film addressing the 90s rather than the 60s is automatically ruled out of order. So it’s only logical that Kiarostami, who was already making films throughout the 70s without Denby’s interest or awareness, has to be measured against a 60s reading of De Sica or Satyajit Ray rather than against a 90s reading of anything.

***

When Denby complains that “it’s hard to scare up much of an audience for” La Cérémonie in 1996, the implication is that New York audiences in the 1960s were storming the cinemas to see L’avventura, Tirez sur la pianiste, Shame, Fellini Satyricon, High and Low, and La Chinoise, which clearly wasn’t the case. In fact, all six of the Viennale films that I saw in 1968 were commercial flops when (or if) they opened commercially — and only Playtime and Petulia were first seen by me in commercial theaters, in Paris and New York, respectively. Speaking for myself, I took a bus all the way from New York to Philadelphia on March 23, 1968 to see La Chinoise at a film club screening two weeks prior to its New York opening, when it ran for just a single week. Part of the reason why I went to such lengths was that Godard was scheduled to appear with the film in Philadelphia; in fact he never turned up, but I never regretted making the trip as a consequence. In fact, when I boarded the bus I discovered that a cinephile friend from college was making the same trip for the same reason. When we boarded the bus back to New York a few hours later, he bought a copy of the Sunday New York Times to bring with us, and I’ll never forget finding there a lengthy irate letter to the editor written by me a few weeks earlier, defending Godard’s films against charges of arbitrariness and lack of structure as propounded by the late Eugene Archer (incidentally the major mentor of Andrew Sarris, and ironically one of the first American champions of la politique des auteurs) in an article published in the Times a few Sundays before. “[Godard’s] most recent films,” I concluded, “are simultaneously investigations into and lessons about how to see, hear and understand our everyday existence. Regardless of how one ultimately judges them, it is irresponsible to call them frivolous; far more frivolous is the critical intelligence which refuses to grapple with them.”

It’s also worth adding that during the week’s run of La Chinoise that started at New York’s Kips Bay Theater on April 3, I and many friends of mine went to see it more than once. Some of these friends were attending Columbia University at the time, and when that college campus was taken over by students a short time later, I couldn’t help but think that Godard’s film had inspired and influenced their militancy. Maybe part of this was wishful thinking, but maybe not: word of mouth traveled more quickly in those days — faster than the New York Times, faster even than television — because there was less media to compete with. Not that the media didn’t exist, but it was believed in much less by people of my generation; all one had to do was read — or, on television, see — the reports of the demonstrations we participated in, against the Vietnam war and on behalf of civil rights, in order to understand that the truth of what happened was available only from fellow demonstrators and other members of the counter culture, not from the “official” channels. And the same thing was true when it came to finding out about movies: the David Denbys and the Eugene Archers of 1968 were not the authorities one had to turn to.

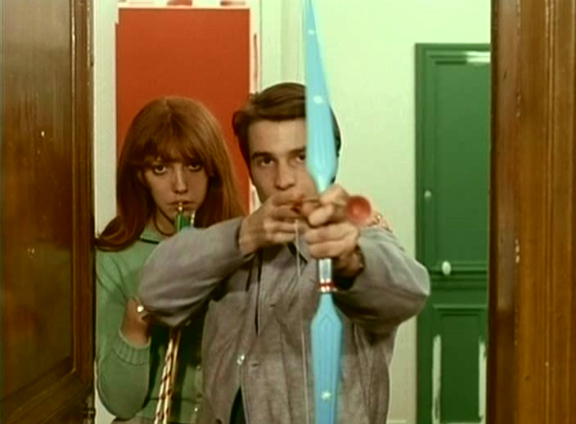

To what extent was La Chinoise a call to arms for Maoist insurrection and to what extent was it merely an inquiry into the ambiguities of student agitation? Wasn’t it possible to feel more sympathetic to Henri (Michel Semeniako), the “revisionist” PCF member of the Maoist cell, than to his pokerfaced comrades who excluded him — much as Bernard Eisenschitz, the PCF member of Cahiers du Cinéma‘s Maoist editorial board, was excluded some time afterwards? That’s pretty much the way I felt, but I wasn’t entirely sure of my position.

No one was quite sure, at least within my purview, but figuring out Godard’s position was secondary at the time to learning what was happening. Unlike all the strictly agitational films made by Godard and others after May ’68 — starting with the Ciné-tracts and Un Film Comme les Autres, which failed to galvanize the same energies — La Chinoise and Weekend were exciting first editions of global newspapers that were suddenly running off the presses and being devoured more for their excitement as reports than for their status as statements or as works of art (which they also were). Whether or not they were masterpieces was strictly secondary to their value as provocations; and the same thing was undoubtedly true even of less overtly political but equally important works like Rivette’s L’amour fou, which I didn’t manage to see until I was living in Paris in the early 70s.

To tell the truth, that’s still the way I respond to many of the films that matter the most to me today when I first encounter them. Even if they take place in decrepit suburban outposts — maybe even in part because they do — Goodbye South, Goodbye, Taste of Cherry, and Straub-Huillet’s Cézanne are also global newspapers with intimations of what’s happening right now, and apart from my perceived duties and responsibilities as a weekly film critic, whether they ultimately measure up to “masterpieces of the past” or even masterpieces of the future is ultimately a side issue to be reflected on later, perhaps during one’s old age. Personally as opposed to professionally, I couldn’t care less whether Taste of Cherry is as good as Sciuscia or Goodbye South, Goodbye can hold a candle to I Vitelloni or Cézanne lives up to Une Partie de Campagne. For the moment, the fact that these films exist at all is important enough. And in this respect, I don’t have to worry about going back to 1968 and finding to my dismay that, like Alabama, it’s no longer home, because in more ways than one I’ve never left.

***

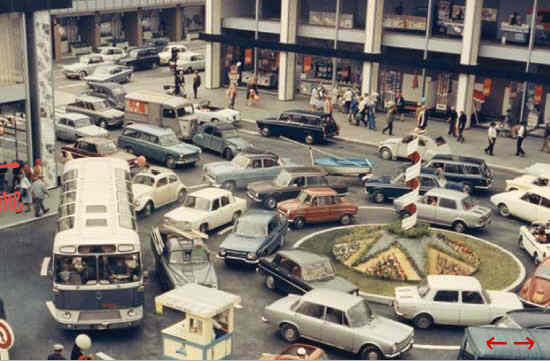

Drugs were an important part of some of my filmgoing experiences in 1968 apart from my unhappy tangle with LSD and Barbarella. My first look at Cassavetes’s Faces, at the New York Film Festival, was under the influence of DMT, a hallucinogen that seemed to condense and compress the film, to frame it under a misty, hypnotic halo, and to intensify the surrounding darkness in the Lincoln Center auditorium. I can no longer remember if I saw Playtime — on two successive Sundays in August, probably at the same medium-sized cinema on Boulevard St.-Germain — after smoking grass or hashish, but suspect I probably did both times. My first look at the film, which is today probably my absolute favorite, intrigued me more than overwhelmed me, above all because of what I experienced as its visual overload and its dispersal of focal points, which being stoned would have only intensified. If grass and movies often seemed to go together like coffee and cigarettes, this is because they both gathered up everyday parts of life and made them into something special and more luminous. After all, I was a befuddled tourist when I saw Playtime, and I was enchanted first of all by the fact that the film addressed me as a befuddled tourist, while speaking about other befuddled tourists. By the second viewing I had become a passionate partisan of the film, but I’m still not at all sure I had yet arrived at any extensive understanding of its greatness. (Its relevance, on the other hand, was never in question; when I returned to New York in September via Orly, I can still recall the delicious sensation of synchronicity I felt when the muzak on the plane was Playtime‘s theme music.)

It’s one of the potential traps of nostalgia to fold back one’s subsequent appreciations of films over one’s initial impressions — one of the central problems for me of Denby’s recollections — and forget that a certain amount of confusion, uncertainty, and ambivalence are likely to accompany one’s first experience of “difficult” and challenging films. With the exception of the collective Loin de Vietnam, which I had already first seen at the New York Film Festival in 1967 — a controversial press screening, as I recall, punctuated by much booing as well as applause, and a film that carried an enormous emotional value for me at the time, in spite of the unequalness of its parts — all six of the Viennale selections that I saw in 1968 are films that bewildered me at times as well as excited me. And even though I regard at least four of them as masterpieces today — Chronik der Anna Magdalena Bach, La chinoise, Petulia, and Playtime — I doubt that I arrived at this conclusion with full confidence the first time that I saw them.

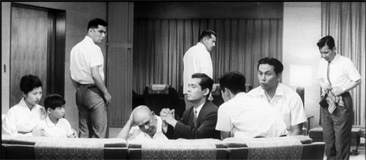

Part of me, for that matter, wasn’t even looking for masterpieces but for something else — a sense of what was happening in the world at that moment, which all of these films except for Straub’s (according to my understanding at the time) piqued as well as satisfied. Partner — which I first saw at the Museum of Modern Art, with Bertolucci in attendance — carried for me such messages as the fact that not only Molotov cocktails, but also Godard, Frank Tashlin, Pierre Clementi, and Lotte Eisner’s book on Murnau had all made strong impressions in Rome as well as in Paris and New York, making me feel — as so much else did during that period, including drugs and politics — that I was living in an international community. And within that community, I must confess, there was also the snobbish possibility of feeling some kinship with an intellectual elite: recognizing the pulsing rhythms of light and shadow from Murnau’s Faust — a film I’d had to travel all the way to George Eastman House in Rochester, New York in order to see — in the visual patterns made by a small chandelier in Partner, or discerning the consumerist satire and primary colors of Tashlin in Bertolucci’s washing machine sequence, made me feel like a privileged member of a new secret society of international cinephiles.

By the same token, Petulia — which I regarded then as a Richard Lester film, and which I tend to regard today as the first Nicolas Roeg film, at least in style and structure — told me, in a manner of speaking, that Alain Resnais, Hollywood, English cinema (as personified by Julie Christie and Lester), and San Francisco were all compatible and even interactive cultural realities to be reckoned with. Some of these things (like San Francisco and George C. Scott) were more mainstream than others (like Resnais-influenced editing), but the fact that they could all coexist in the same film gave me reason for hope. These sort of juxtapositions weren’t all the things that Partner and Petulia said to me, by any means, but they were an important part of their discourses, and they motivated me to understand them better. (The extension of Godard by other means was also what I was looking for and mainly gleaned from Michel Cournot’s Les Gauloises Bleues, even if I didn’t understand most of the French, when I saw it at the St.-Germain-des-Prés Drugstore in late August.)

It was a sense of spiritual and metaphysical interconnection, like what I felt when I heard the Playtime theme music on the plane at Orly. It was not so different, really, from having stayed at the Hotel Stella in Paris, reportedly the only such establishment on the street that had allowed student guerillas to sleep on the floor of its lobby during the aftermath of the May Events; or walking down rue Monsieur le Prince one day in June or July, past the jubilant political and erotic graffiti that decorated that neighborhood all summer long, to find my eyes and nose suddenly filled with the sting of invisible tear gas; or stumbling upon a belated police charge on the same street another day, which led me to race off down a side street to relative safety. Most of the ravages of uprooted trees and disengaged cobblestones used for student barricades in May were still visible on Boulevard St.-Michel only a block away, even when by the summer’s end some of the smaller streets were being paved to remove the possibility of cobblestones being pried loose again. All summer long I heard heroic tales about some of the recent skirmishes, and the mood they carried was closer to euphoria than to disillusionment, which would come only later. All kinds of energies had been set loose in the world — the same kind of energies I had felt when I visited the occupied campus of Columbia University the previous spring, when I had attended a “Town Hall meeting” (I no longer remember about what) in early February, or when, back in New York during the first two Mondays in October, I attended The Living Theater’s productions of Frankenstein and Paradise Now at Brooklyn’s Academy of Music. (At the second of these evenings, the audience was even ahead of the actors. At the U.S. premiere of Paradise Now in New Haven, Connecticut in late September, the whole production, performers as well as spectators, many of them naked or semi-clad, had charged into the street during the final act, leading to several arrests. By the time the show reached Brooklyn three weeks later, some members of the audience — in anticipation of the birth of the Rocky Horror Picture Show cult eight years later — started undressing and lighting up joints before the actors did.)

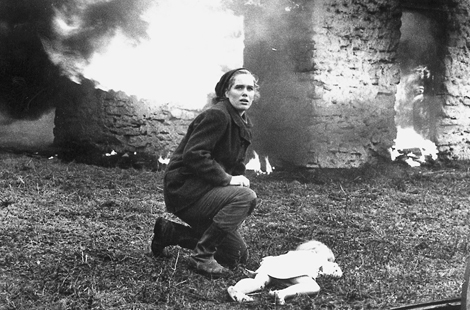

The very theme of Loin de Vietnam was this feeling of interconnection — the conviction that you could still say something important about an American war in Vietnam when your base of operations happened to be France. By 1968 I had already become acquainted with four of the seven filmmakers who contributed to this feature — Godard, Resnais, Claude Lelouch, and Agnès Varda, but not yet Joris Ivens, William Klein, or Chris Marker. Yet it was probably Klein who affected me the most when he focused on how an American Quaker, Norman Morrison, following the example of several South Vietnamese Buddhist monks, protested the war by burning himself alive.

Like many, perhaps most Americans at the time, I already knew who Morrison was and what he had done, but all I had heard about his act from friends and colleagues was that he was a madman whose suicide had accomplished nothing. What Klein, an American expatriate in Paris, had shown me was that what Morrison had done meant a great deal, not only to his own family, but also to the North Vietnamese, who had even named a street after him. These were simple facts, but nothing I had come across in American journalism at the time had made them available. Consequently, the importance of this information — like the importance of all the new films that mattered most to me in 1968 — wasn’t part of the media as I understood it then, but part of something else. It was like receiving a letter from friend who lived far away but knew exactly what I was thinking. That’s still what matters most to me in movies, and the major legacy of 1968 for me is the certainty that there are still friends of this kind scattered across the globe, regardless of the state of our postal delivery.