From Film Comment, September-October 2001. — J.R.

Though I haven’t yet seen a 35mm transfer of A.B.C. Africa, Abbas Kiarostami’s first digital video, I’ve had the benefit of viewing his 92-minute rough cut and his 84-minute final version. It’s obvious that this documentary is a departure for him in many ways, being his first feature made outside Iran and his first work that’s primarily in English. It’s also possibly his most accessible picture to date, confirming that Kiarostami has become as “multinational” or as transnational as he is Iranian — which may help to account for his worldwide reputation.

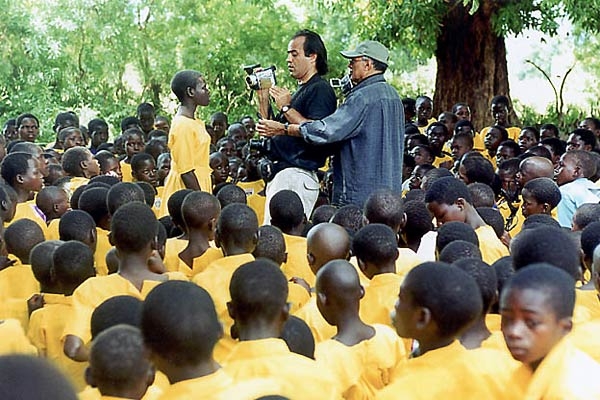

Shot with two cameras by Kiarostami and his assistant Seifollah Samadian, who also helped with the editing, A.B.C. Africa was made at the request of the UWESO (Uganda Women’s Efforts to Save Orphans) program, part of the International Fund for Agricultural Development. A letter of thanks from the IFAD’S Takao Shibata, dated March 23, 2000, arrives in Kiarostami’s fax machine in the opening shot, explaining how civil unrest and AIDS have left Uganda with about 1.6 million children who’ve lost one or both of their parents — and how a film by him might “sensitize people around the world [to] the devastating dimensions of this tragedy.”

As a fulfillment of this assignment, A.B.C. Africa initially seems to have scant relation to Kiarostami’s earlier films, apart from many shots of landscapes from moving cars and the frequent visibility of Kiarostami himself. Furthermore, the emphasis on orphans joyously singing and dancing — which was even greater in the rough cut — might take some viewers aback. The essential facts, most often conveyed through onscreen or offscreen interviews with the women who take care of the children, are never shirked or glossed over. One unforgettable sequence, set inside a hospital, culminates in the fashioning out of cardboard of a makeshift child’s coffin, which is then transported on a bicycle. All the same, the film is as much a celebration of the kids’ resources as it is an exposure of their plight, and bears an uncanny kinship at times to Hollywood musicals with its bold colors and sheer energy. For a filmmaker who for some time has restricted his use of music to final sequences, the many music-based moments in A.B.C. Africa mark a significant departure for Kiarostami, who says he made the film the way he did because singing and dancing is to a large degree what he encountered in these children. (The impromptu nature of the shoot is made apparent by the fleet movements, hesitations, and shifting paths of the DV cameras as Kiarostami and Samadian follow, anticipate, or catch up with various children.)

Over A. B. C. Africa‘s second half, the apparent artlessness proves to be deceptive; this is unmistakably a Kiarostami work, albeit one that takes several bold steps toward redefining his art. And its being a video is part of that redefinition. Kiarostami has made it clear that he wanted to switch to DV for ethical reasons — the desire to interfere as little as possible with the people he was shooting. And as critic Mehrnaz Saeed-Vafa told me, there’s an intriguing carryover from his previous feature: in contrast to all his earlier work, women often turn out to be the dominant adult figures shown or discussed, apart from the male protagonist.

Though he’s still getting used to DV technology, which caused delays in the editing, Kiarostami has not yet shown any sign of ever wanting to switch back to film. I expected this new position to entail a fresh aesthetic, yet he seems to have proceeded on the premise that A.B.C. Africa is simply a “film” made with more portable equipment, and thus in a more equitable relationship with the people he shoots. The only video technique I noticed was the quick, almost subliminal use of lap dissolves in the final sequence between clouds seen from a plane and briefly glimpsed black-and-white photos of orphans. (Originally, this was accompanied by Haydn; then it was the sounds of the plane over traces of The Blue Danube, although the latter was removed in the final transfer.)

Kiarostami has argued on occasion that he sees no clear-cut distinction between documentary and fiction. Part of this sense of ambiguity can be seen in the frank presence of the filmmakers — followed at the end of the film by their more conventional absence from the shots, which encourages us to forget about them. Another part of it can be felt in the habitual transformations of Kiarostami’s offscreen interactions with his non-professional actors into fictional dialogues with his onscreen surrogates. When I interviewed him last year, he confirmed that when the boy Farzad in The Wind Will Carry Us blushingly insists to the “engineer” Behzad, “I know … you’re good,” this was actually Farzad’s response to Kiarostami, after the director asked the boy if he thought he was bad — knowing full well that the boy disliked him (though he liked the actor playing Behzad).

Insofar as both Taste of Cherry and The Wind Will Carry Us share the theme of an individual’s isolation from his surroundings, each film, if one bears Kiarostami’s editing tricks in mind, can be regarded as a complex auto-critique exploring the issue of privileged filmmakers shooting poor people. (When I suggested this notion to him, however, he was quick to correct me regarding Ugandans: “Not poor inside.”) A.B.C. Africa makes this explicit by emphasizing not only the presence of Kiarostami and Samadian but also their ritzy accommodations. A dialogue in Farsi between the filmmakers that begins in the darkness outside their hotel, along with the video’s philosophically and spiritually inflected humanism, belatedly reminds us that this is, in some respects, an Iranian work after all.

After more darkness, then lightning, thunder, and rain, the dialogue resumes the next morning in a half-ruined house occupied by a large family. Though I miss the lovely version of “Autumn Leaves” by a male singer accompanied by solo guitar used with this scene in the rough cut, the minimal, faintly heard guitar tune replacing it is certainly more subtle, and this segment remains the work’s lyrical climax, with a mood of melancholy hope recalling the post-earthquake setting of the director’s Life and Nothing More.

Our introduction in English to a white Austrian couple adopting an orphaned baby broaches the question of what this video might mean to the West. In the closing sequence, as the couple and child board a plane for Austria, we’re encouraged to wonder what will happen to all three when they arrive at the other end. The fact that we don’t see Kiarostami or Samadian as fellow passengers means that A.B.C. Africa has by this time effected a quiet and permanent gear-shift from a non-fictional form to a fictional one, with the role of moral witnesses passing subtly from the filmmakers to us — a modulation that tactfully brings up the question of our ultimate role in these proceedings. This is a fairly unobtrusive way of achieving the goal assigned to Kiarostami in the opening fax, and I hope that the members of the UWESO and IFAD are as pleased with the results as I am.