A chapter from my book Film: The Front Line 1983 (Arden Press, 1983), still in print. — J.R.

Jacques Pierre Louis Rivette

Born in Rouen, France, 1928

Perhaps no single figure in this survey dramatizes the contradictions of the avant-garde film as an institution and social force better than Jacques Rivette — a major filmmaker who has consistently been denied credentials, recognition, or any sort of protection by the “official” avant-garde establishment, even though his work has generally been shunned just as consistently by the mainstream power structures. Who, then, gives a damn about Jacques Rivette? More people than either establishment cares to acknowledge or deal with. As someone who has written a good deal about Rivette, programmed his films in three countries, and edited the only book devoted to him in English (or French), I can report that everywhere I go, I meet passionate Rivette fanatics.

In London, I once met an American who dutifully translated most of Rivette’s old Cahiers du Cinéma reviews in his spare time, simply for his own amusement. I also once shared a Hampstead maisonette with a brilliant Israeli-born lecturer in philosophy of art whom I took to a screening of the four-hour Out 1: Spectre; he spent most of the rest of the night telling me why it was the greatest film ever made — only a sleepless day or so before he temporarily flipped his lid and tried to chop down part of our kitchen wall with a hatchet. A friend who lives in Texas, collects and sells movie posters, and issues intense and thoughtful “auteurist” catalogs of his collection from time to time, has been intermittently working on a video remake of Out 1: Spectre for several years. A Belgian Rivette freak of my acquaintance was recently sent from New York to Paris by Vanity Fair to interview the director; I hear that he returned empty-handed, but will be writing the piece anyway. I know many women who consider Celine et Julie vont en bateau their favorite movie about female friendship, and Bernadette Lafont once told John Hughes, another one-time Rivette buff (see his delirious reflections on the now out-of-print Rivette: Texts and Interviews, published by the British Film Institute in 1977, in the May-June 1978 Film Comment), that Rivette “is a kind of Mao and his films are a Cultural Revolution…” A Cuban friend currently living in Miami has a gigantic Duelle poster taped to his ceiling. In Brittany, during the shooting of Noroit in 1975, I chatted with a Scandinavian journalist and Rivette aficionado based in Rome who told me disquieting anecdotes about the shooting of L’Amour fou in 1967, some of which she also apparently watched.

These are only a few of the Rivette crazies I’ve run into, and like any true Rivette obsessive I could undoubtedly extend my list for days if such possibilities were available to me. The fact that none of them is supposed to exist or matter or have as much taste or savoir faire as any of the official traffic cops who rule avant-garde (as well as “art film”) discourse only makes them that much more passionate and fanatical about their cult enthusiasm: the unexpected mob scenes that occurred at the last New York screenings of Out 1: Spectre and Merry-Go-Round — probably Rivette’s best and worst films, respectively — with dozens of people having to be turned away on each occasion, only testify to the resilience of this growing “secret” society over the past several years. It may help to account for the curious, anomalous position of Rivette as a filmmaker who still manages to get new films financed, even though he frequently can’t get them shown: like all the great film and filmmaking obsessives, his work thrives on legends, and the 13-hour version of Out 1 is almost as scarce a Holy Grail as the longer versions of Greed. (1)

Considering the fact that only Rivette’s first feature has ever been released in this country with any seriousness — and nothing has been released at all since the belated and very half-hearted launching of Celine et Julie by New Yorker Films several years ago — it’s hard to know what constitutes “new” or “old” work in this context. I’ve restricted my range here to his last three features. (Readers interested in investigating the previous one, Duelle, should consult my article with Gilbert Adair and Michael Graham in the Autumn 1975 Sight and Sound about the shooting of Duelle and Noroit, and my reviews of Duelle in my Edinburgh Festival coverage in the Winter 1976/77 issue of the same magazine and the September-October 1976 Film Comment.)

If every new Rivette film generally marks a decisive break as much as a discernible development, Part III in the projected but subsequently abandoned Scenes de la vie parallele — the second and last film made in the tetralogy, after Duelle — reinforced that principle with a vengeance when it received its world premiere at the London Film Festival in 1976. Rather like the pitiless Chuck-a-Luck in Fritz Lang’s Rancho Notorious, enlisting new players and expelling old ones with every spin of the wheel, Rivette’s precarious games have always been predicated on enormous risks; but unlike that vertical roulette board, they are not necessarily played to be won. Demonstrating this fact with shocking clarity, Noroit enters a treacherous, kaleidoscopic no man’s land where the very notion of judgment in any ordinary sense — the director’s or ours — largely seems beside the point. The old-fashioned term for this realm is “experiment.”

What are some of its ingredients? (1) A pirate tale fashioned out of diverse parts of Moonfleet, House of Bamboo, various samurai sagas, and Tourneur’s The Revenger’s Tragedy, set on “a small island in the Atlantic, off the coast of a larger one” in no locatable period, and structured, like Duelle, on the successive elimination of every character, developing towards a confrontation between a “moon ghost” and a “sun fairy” (although without very much of the mythical baggage underlying Duelle, save a few references to it in the closing sections). (2) A few English lines of Tourneur, violently wrenched out of context and recited by the avenging ghost Morag (Geraldine Chaplin) and/or her accomplice Erika (Kika Markham), as incantation, as simple quotation, or in a hammy style suggesting Land of the Pharoahs — playing, like Eduardo de Gregorio’s dialogue, on a variety of uncanny emotional registers that, along with facial and body movements, range from the nightmarish to the parodic. (3) Music improvised by a visible trio who contrive to blend “modern” and “primitive” elements on an assortment of instruments, with a use of direct sound throughout offering another broad palette of possibilities, from the wind and sea to the squeaks and squishes of the lavender leather pants suit worn by Giulia (Bernadette Lafont), sun fairy and head of the pirate clan. (4) A systematic development towards ritual, dance, fantasy, gibberish, and total abstraction of the narrative through camera distance and darkness — coupled with facial masks, red filters, and silent 16mm black-and-white footage in the aggressive last sequence — all of which periodically makes it difficult or impossible to identify certain characters and transforms the coordinates into those of pure spectacle. Even the film’s supposed English subtitle, Nor’wester, sounds more like a perverse joke than a significant clue to anything — rather like the fake Middle English subtitles used to translate parts of the gibberish French in the closing sequence.

Noroit contains the most beautiful images and sounds of any Rivette film, and the fewest indications of what a spectator is meant to do with them, apart from look and listen. When I watched a week or so of the film’s shooting, I was amazed by the unnatural amount of sinister suspense that could be generated during successive takes, especially whenever the three musicians were playing, because their improvisation guaranteed that one could never be quite sure how any take would register — despite the lack of any improvisation in the plot or dialogue and the careful working out in advance of the camera movements.

The existential tension generated by this uncertainty — a hallmark of Rivette’s style from film to film, whatever the differing strategies for bringing it about — has led many critics to draw a blank on the film, or even to retreat in terror (like the critics of Cahiers du Cinema, who have avoided writing about the film). The disquieting implications of the film and its “images of castration” (as a film about female pirates) have perhaps led many commentators to conclude that any sort of analysis might be messy and embarrassing — as if it weren’t a film at all, but a form of unsuccessful psychoanalysis.

While the plot is generally easier to follow than the one in Duelle, the shifting levels of mood and tone produce a sustained uncertainty of response — reaching an apotheosis in the mutual stabbing and subsequent laughter of Giulia and Morag in the final shot, which perfectly encapsulate the film’s clashes and contradictions. On the level of identification, a subjective pan from beach to fortress in the first sequence initially designates Morag as the viewer’s reference point. But in a film that seems executed according to principles of discontinuity, plot itself — by sheer virtue of its continuity — ultimately becomes the least relevant aspect of its experience. And by the time Morag is back on the beach near the film’s end, by the time a comparable pan across the Atlantic is abruptly introduced in the middle of another camera movement following Erika around a room in the fortress, the subjective reference has significantly been raised (or reduced) to the level of abstraction, like a phrase in a foreign tongue.

Many of the preoccupations can be traced back to Rivette’s seminal review of Lang’s Beyond a Reasonable Doubt in Cahiers du Cinema (No. 76, November 1957). There one finds the notion of a “totally closed universe” (all the more paradoxical in Noroit, which abounds in spectacular vistas and spacious interiors), where a director who “always looks for the truth beyond the probable… looks for it here by entering the improbable.” Equally present is an aesthetic of self-destruction, whereby each scene is restricted into a succession of “pure moments” and whereby anything that might fix them to reality is “reduced to a condition of pure spatio-temporal reference, without embodiment.” In these moments “the characters have lost all individual value, are no more than human concepts,” defined only by what they say or do. We are left with the strictly material space and existential duration in which an actor moves. (In fact, in reference to the subsequent Merry-Go-Round, Rivette told David Sterritt of the Christian Science Monitor — a perceptive and faithful Rivette supporter — “I care more about the grace of the actors’ gestures and the quality of their voices than what they actually do or say.” To my mind, the most radical innovation of Out 1: Spectre, because of this interest, is the effective obliteration of any distinction between “good” and “bad” acting: everything becomes potentially interesting as “behavior.”)

These are, of course, the conditions of the theater rehearsal, examined at length in Paris nous appartient, L’ Amour fou, and Spectre, where the actual end-point of “performance” is never reached. The radical departure of Noroit is to resume that inquiry (with improvised music assuming the role of the relatively “fixed” percussion in L’ Amour fou and Spectre, which increases the almost primitive sense of perpetual tryout) without the narrative-illusionist pretext of the rehearsal to “place” it, apart from a few perverse instances that work more as displacements: Morag’s murder of Regina, which serves as “rehearsal” for its re-enactment by Erika and Morag before Giulia and her court; the rehearsed swordfight between Ludovico (Larrio Ekson) and Jacob (Humbert Balsan), merging imperceptibly along with the music into a performance staged to confound Erika. (Considering the ambiguity of behavior in relation to “real” rehearsals, I should cite my own mislabeling of the production still from Noroit on the cover of my Rivette book — unfortunately unavailable for reproduction here — as “Rivette directing Babette Lamy and Daniele Rosencranz,” when further reflection revealed that he is actually directing an unseen Geraldine Chaplin — showing her how to whisper into Lamy’s ear.)

The most characteristic rhythmical pattern set by the delivery of lines and music, the movements of actors and camera, is one of stopping and starting, with odd-shaped pauses falling in between, while the tempos often tend to be either slower or faster than those favored in most Western dramaturgy, and somewhat closer to those associated with dramatic and ceremonial forms found in Japan. Both of these strategies converge in the climactic “masked ball,” lit by bonfires and punctuated by pageant-like repetitions — a choreography of confrontations and crossing vectors isolated in time and space, whose counterpart in Duelle is the central dance hall sequence, where the mirror breaks and the goddesses meet. The madness and hysteria of the Tower of Babel is basic to every Rivette film, from Paris nous appartient to Le Pont du nord; the maniacal giggling of Celine et Julie which irritates some spectators is merely one of the less sinister manifestations of it. Prior to Noroit, each film distanced this aspect by providing an audience with a phenomenological world to cling to; even Duelle, thanks to its cozy film noir references, nostalgic piano music, and Cocteau quotations, intermittently allows one to “enter” its reinvented Paris as a potential inhabitant. But the increased remove from any semblance of “lived experience” in Noroit — which makes it a much more exciting and daring work than any Rivette film since Spectre — also leads to a certain shrinkage of possible affect whereby the film becomes a “documentary” of a tournage and montage on the one hand, a capitulation to Babel itself on the other. Acknowledging the brilliance of William Lubtchansky’s photography, the precision of the frontal camera movements and long takes (both evocative of Mizoguchi), the caustic bite of de Gregorio’s dialogue, the dancer’s grace of Ekson, the chilling laughter of Lafont, the howls and mimes of Chaplin, the beauty of Markham, the savage power of the music and, above all, the continual shifting of gears, placing one at a tangent to all these elements as they struggle independently or collectively towards representation, one is nevertheless obliged to ask just where Rivette’s experimentation is headed.

So far, Merry-Go-Round and Le Pont du nord (North Bridge) have provided only partial answers. Each can be regarded in a different way as a step back from some of the radical implications of Noroit and an attempt to find new ground as well. Neither film to my mind is an “essential” Rivette work, although both certainly have their interesting facets.

Merry-Go-Round came about through a rather unexpected occurrence: Maria Schneider announced that she wanted to make a film with both Rivette and American actor Joe Dallesandro. At this point, Rivette, recovering from a nervous collapse that halted the shooting of the third feature in Scenes de la vie parallele only a few days after it started (a love story starring Albert Finney and Leslie Caron), decided to make a thriller as a sort of interlude from the tetralogy. Once again, he had as his producer Stephane Tchalgadjieff, the remarkable producer of Out 1 (both versions), Duelle, and Noroit — as well as many other exceptional and unusual films over the past several years, ranging from Bresson’s Le Diable, Probablement to Duras’s India Song to Straub-Huillet’s Fortini-Cani. In addition, Rivette re-enlisted many of his former collaborators, including scriptwriters Eduardo de Gregorio (who had worked on Celine et Julie, Duelle, and Noroit) and Suzanne Shiffmann (who had worked on Spectre), director of photography William Lubtchansky, and editor Nicole Lubtchansky (the former’s wife, who had already worked with Rivette as editor on everyone of his films since L’Amour fou, excepting only the shorter version of Out 1).

Some of the secondary actors chosen were also veterans of previous Rivette films, including Daniele Gegauff (née Rosencranz) (Noroit), Francoise Prevost (Paris nous appartient), Michel Berto (Spectre), and Hermine Karagheuz (Spectre, Duelle); others included Sylvia Meyer, Maurice Garrel, Dominique Erlander, Frederic Mitterand, Jean-Francois Stevenin, and Pascale Dauman. And Rivette once again hired musicians to work on the film-in this case, bassist Barre Phillips and bass clarinetist John Surman — but this time chose to integrate them with the fiction in a completely different manner, cutting back and forth periodically between the story and the two musicians improvising their free jazz in a dimly lit studio — with only very brief overlaps, if memory serves, of their music heard off-screen with the film’s action. Tom Milne synopsized the film as follows in the Winter 1978/79 Sight and Sound:

In New York and Rome, a man and a woman who do not know each other (Joe Dallesandro and Maria Schneider) each receive a summons to the same mysterious assignation in Paris. No one turns up at the rendezvous, and their contact — his girlfriend, her elder sister — proves to have disappeared in sinister circumstances, possibly kidnapped. They duly set out on the trail of a dark conspiracy, filmed largely with a subjective camera: not quite so systematically as in The Lady in the Lake (there are objective shots and sequences), but along the same lines and designed to shade the atmosphere of mutual suspicion into a kind of fantasticated terror. Originally, the idea was for the couple gradually to rediscover their childhood in the sort of regression planned, but never finally realized, for L’Amour fou. Instead, their fear now creates a sort of parallel universe, and the suburban surroundings of the thriller, “the dangerous, sad city of the imagination,” gives way to a natural world (sand dunes, a forest) into which they each project the other and where they are assailed by hounds it la Zaroff, snakes, a medieval knight, and suchlike terrors of the mind. […]

The above account, based on an interview with de Gregorio while the film was being edited, may differ in one or two particulars from the finished film, but is substantially what I recall seeing at Manhattan’s Museum of Modern Art in February 1980. Rivette himself, who was present at the screening, told me he regarded it as his worst film, and I would be inclined to agree, although I regret not having had a second look at it. From all the accounts that I’ve heard, the project was largely sabotaged by a lack of compatibility between Schneider and many of the others working on the film, including Rivette and de Gregorio; an original plan which involved a certain amount of improvisation from the actors had of be discarded more or less in midstream, and, as it stands, the strongest and most arresting portions of the film, at least in memory, tend to be those not involving dialogue (and, in many cases, those not involving Schneider) — particularly the use of music and the sequences in the sand dunes and forest alluded to by Milne. In the latter, significantly, Hermine Karagheuz replaces Schneider — a tactic recalling Bunuel’s in That Obscure Object of Desire — and the mainly silent confrontations between her and Dallesandro have an abstract and quasi-comic aspect that to my mind recalled Road Runner cartoons. Otherwise, the complex and paranoid plot is not easy to follow, especially in its latter stages; and rather than attempt the impossible task of paraphrasing it here, three years after seeing the film, let me conclude this account with Rivette’s own statement about the film that was included in the program notes:

I like a film to be an adventure: for those who make it, and for those who see it. The adventure of this filming, I must admit, was a bit fitful: the course which was established at the outset was corrected many times, in response to contrary winds, lulls, or gentle breezes. I only hope that the finished film, with all its detours, keeps something of the dangers of the crossing, of its uncertainties, of its unclouded moments-even if, at the end, one notices that perhaps the voyage has been circular: like a “merry-go-round.”

Rivette has described Spectre as an updated critique of Paris nous appartient — his first feature, about political conspiracy — ten years later, and Le Pont du nord (North Bridge) as still another updated version of the same theme. It also seems to announce an end, temporary or otherwise, to Rivette’s preoccupation with modernism in the other arts (particularly music and theater), which reaches a certain culmination in Noroit, pointing in the direction of a more popular narrative (and hence less radically avant-garde) tradition. In this respect, one could say that North Bridge reaches back towards Celine et Julie in the same general way that Noroit reaches back towards Spectre — and hence could serve, like Celine et Julie, as an excellent introduction to Rivette’s work as a whole. One therefore had hopes that North Bridge, by getting a U.S. release, could serve as an Open Sesame in this country for Rivette’s more difficult work. But these are conservative times, and even though Rivette’s audiences in this country have repeatedly shown themselves to be well in advance of most American critics and distributors, their enthusiasm is not enough to grant North Bridge an opening. (A comparable deadlock seems to keep even a cult favorite like Celine et Julie, which does have a distributor, firmly under wraps as far as theatrical showings are concerned: in New York, at least, the film is never revived by New Yorker Films in any of its revival programs — to the extreme frustration of many buffs who discovered Rivette via North Bridge at the 1981 New York Film Festival, but can’t see any more of his work.) For a detailed plot summary of North Bridge, let me once again turn to one of my colleagues. David Ehrenstein, writing in the July 20, 1982 Los Angeles Reader:

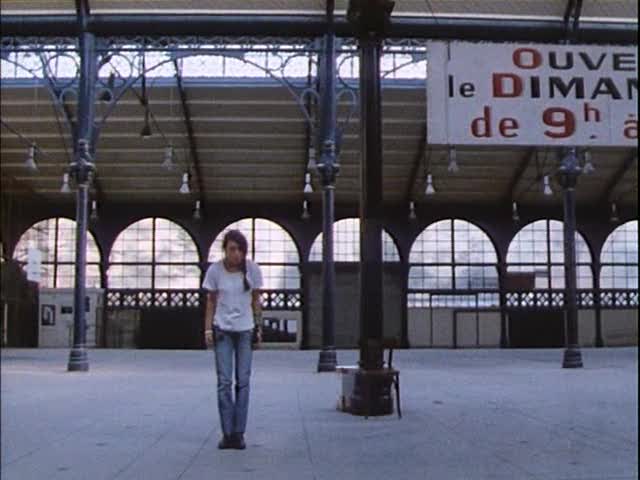

Just out of prison on a robbery charge for which she claims to have been set up, Marie (Bulle Ogier) is ready to start her life anew. When she meets up with Baptiste (Pascale Ogier), Marie gets her chance to do so, though not in the form she probably had in mind. A thoroughly wacked-out punkette given to ominous, haughty stares and Bruce Lee karate stances, Baptiste is convinced that she has been chosen to be Marie’s “protector” after their paths cross three times in the street. “Once is an accident, twice is chance, three times is fate!” A Rivette paranoid in the grand tradition, Baptiste, when queried about her past, claims to come from “elsewhere.” Seeing secret policemen whom she calls “les super-Max” on every corner, she babbles on endlessly about the plots that supposedly spin about everyone on earth. “We’re all under very careful surveillance, you know.”Friendless, at emotional loose ends following her incarceration, and nearly crippled by a claustrophobia so severe that she is unable to stand being indoors for even the shortest period of time, Marie really does need someone’s help and protection. Moreover, the curious behavior of her gambler boyfriend (Pierre Clementi) begins to make Marie suspect that Baptiste’s nutty ideas may have some truth in them. The viewer at this point is inclined to agree. What’s the mysterious black valise that Marie’s lover Julien keeps so closely guarded? Why is he perpetually making brief assignations with her, then suddenly rushing off on some appointment or other? Who is the strange man (Jean-Francois Stevenin) who keeps popping up on streetcorners near Baptiste and Marie? Stealing the black valise, the two women discover a file of numbered newspaper clippings about recent political scandals and the unsolved murder of a leftist leader, plus a map of Paris inscribed with a strange circular design. In an ingenious attempt to break the code, Marie and Baptiste convert the map into a game board and use it to traipse around the city investigating the out-of-way spots to which it leads them — building sites, vacant lots, an abandoned Hebrew cemetery. At each location they encounter the unidentified stranger, now accompanied by another nameless gentleman clad in an official-looking, dark business suit. Baptiste’s conspiracy theories have slowly but surely been transformed into reality. […]

The file of clippings concerns specific scandals of the Giscard d’Estaing regime, and the locations refer to various municipal corruptions associated with that period (e.g., the ruins of slaughterhouses in La Villette which were built and then demolished before they could be used, due to safety hazards). Rivette has indicated that the film was made prior to the French elections and with the pessimistic expectations that the same regime would remain in power; so the unexpected election of Francois Mitterand obscured and blunted part of the film’s intended impact. Rivette conceived of Marie as a continuation of the anarchist character played by Bulle Ogier in Fassbinder’s The Third Generation (1979), after she gets out of prison. Her claustrophobia was occasioned by the film’s cut-rate budget, which led to the decision to shoot the film exclusively in exteriors.

Working once again with Suzanne Schiffmann (scriptwriter) and Nicole and William Lubtchansky (editor and cinematographer, respectively), as well as with two leading actresses whose off-screen relationship is more than professional (Pascale Ogier is Bulle’s daughter, just as Juliet Berto and Dominique Labourier were friends prior to making Celine et Julie), Rivette turns his complex plot into an absorbing and offbeat travelogue of Paris, beginning with a stone lion (Le Lion de Delfort) and virtually ending with a children’s slide perceived as a dragon. In mystical terms, one might even add that Marie’s little red Plan-Guide de Paris neatly assumes the same function as Julie’s book of magic spells in Celine et Julie in summoning up her shadow-double (in Marie’s case, Baptiste). And in keeping with the tradition of Paris Belongs to Us and Out 1: Spectre, North Bridge opens with a title announcing a precise date, coupled here with a witty paraphrase-parody of the title at the beginning of Star Wars: “Long ago and far away/October or November 1980.”

An explicitly quixotic fairy tale, North Bridge leads from such enchanted moments as Baptiste putting her capsized motorbike out of its misery — cutting a wire to stop its motor the way that a cowboy shoots his wounded horse — to Marie’s encounters with Julien/Clementi (amorous) and Max/Stevenin (political), ending up in such fantasy realms as Baptiste’s weird, “naturalistic” confrontations with a spider’s web spun out of a fiberglass sprayer and the children’s slide perceived as a dragon (which, incidentally, exhales fire). For former bank robber and prison convict Marie, waiting around for her dreamboat Julien to bump her off, Paris is a conspiratorial spider’s web, a marked city map, and intermittently a kid’s game of “Chutes and Ladders” (known as “Snakes and Ladders” in England). For Baptiste — an abstract cipher without a past, for whom “life is a reign of terror,” projecting her staccato teenage body through angular karate stances, headphone music, and ugly industrial faces — Paris is the tail of the dragon, a city of eyes to be defaced (she habitually slices the eyes out of people in posters) and spies named Max to be faced. (“A maximum of what?” someone asks her, and she replies, “A maximum of Maxes.”)

Together, Marie and Baptiste constitute one more Rivettean female couple whose mysteriously fateful and existential encounter transforms Paris into the city of their mutual desires. But the Paris of North Bridge, interestingly enough, isn’t the same city as the Paris of either Duelle or Celine et Julie, just as the equally different Paris of Spectre isn’t the Paris of Paris nous appartient. As Dave Kehr — who had the good taste to put North Bridge as well as Straub-Huillet’s Too Early, Too Late in his ten best list for 1982 — pointed out in the Chicago Reader, “Of all the survivors of the French New Wave, Jacques Rivette remains the most thoroughly unpredictable (Godard is predictably unpredictable). His critics charge him with changing his theories too quickly from film to film, but it seems to me that an inconsistency of approach is more of a virtue than an evil in the search for new ways of making movies.”

END NOTE

- The effort of a few American critics to link up Jean-Jacques Beineix’s Diva with Rivette, while no doubt well-intentioned, seems to me to be based on a fundamental misunderstanding of Rivette’s aesthetics. My own two primary choices of recent films that could be called properly (and interestingly) Rivettean in a “commercial” context would be Alan Rudolph’s Remember My Name (which Rivette himself has identified as an imitation) and the controversial middle section of Wim Wenders’ The State of Things (including a semi-deserted “house of fiction” as resonant with narrative meaning as the country houses in Out 1: Spectre and Celine et Julie vont en bateau — not to mention the curious “first-person narrator” house in Eduardo de Gregorio’s Sérail, which turns the convention of the fiction-laden house into an actual female character that devours its hero).

Excerpted from Film: The Front Line 1983 (Arden Press, 1983), p. 162-74.