Written for the 120th and final issue of Trafic, Fall 2021, where it appears in Jean-Luc Megus’ French translation. Contributors to this special issue were invited to write about something treasured, bearing in mind the quote from Ezra Pound that’s cited. — J.R.

“I never know how I should end my solos,” John Coltrane reportedly once said to Miles Davis, to which his boss gruffly replied: “Try taking your horn out of your mouth.”

Coltrane’s conceptual orientation versus Davis’s blunt practicality can be felt in the former’s symmetrical, multi-note flurries and rude honks up and down scales, furiously covering almost every available silence with his “sheets of sound”, and the latter’s jagged, elliptical smears and little-boy cries separated by sudden pauses that often register like either interruptions or abrupt afterthoughts, second-guessing himself.

An almost sexual alternation of giving and withholding in a jazz solo becomes a tug of war between conflicting formal as well as sexual impulses — Davis’s version of coitus interruptus versus Coltrane’s giddy flirtations and unresolved foreplay. It persists throughout director Fei Mu’s and screenwriter Li Tianji’s extraordinary Spring in a Small Town (1948), a troubled and troubling piece of cinematic chamber music that seems all the more passionate yet intensely bottled up during the romantic and sexual frustrations of the Coronavirus pandemic. This torrential yet quiet film is full of both poise and chaos, control and abandon, starting with an overload of determinations regarding time, place, character, and latent passions and ending unexpectedly with an almost arbitrary sense of abstraction about the future. In the final shot, the heroine, outdoors with her husband, is happily pointing to some distant vista that remains conveniently unseen and unidentified — as if she’s dreaming of a postwar (or post-pandemic) utopia where sexual and romantic fulfillments finally become possible again, at least with her husband if not with her lover. It’s an attempt to end the film with “mature”, adult desires, yet it’s the adolescent ones that dominate, painfully, in what precedes them.

For many years, one of the persistent mysteries surrounding this masterpiece is why Chinese cinephiles commonly consider it the greatest of all Chinese films while Westerners typically consider it not so much beneath their consideration as outside it –- seldom seen or discussed, and, until recently, not often available with subtitles in decent prints. Could its own withheld emotions be too Asian for Western tastes? And if so, why does it speak to me so directly during the protracted loneliness and stifled social interactions of the pandemic? Could my desire to write a mimetic appreciation of its strangled feelings have succeeded too well with its first reader, who felt it lacked emotion? Did I simply take the horn out of my mouth too soon? Or was I unconsciously trying to become Asian myself by hiding my feelings about it?

Shot quickly as a B-film, sandwiched uneasily between the Sino-Chinese War and the Communist Chinese Revolution, Spring in a Small Town isn’t even mentioned in Jay Leyda’s 1972 Dianying: an account of films and the film audience in China (although Fei Mu does get profiled in the same book), probably because the political incorrectness of Fei Mu’s last feature led to its suppression during that period. This undoubtedly makes it more resonant for Chinese people discovering it after new prints were struck in the early 1980s, and perhaps more perplexing for Westerners such as myself who have only a dim understanding of its historical context. But it’s worth stressing that in 2005, the Hong Kong Film Awards Association named it the greatest of all Chinese films, and the relevance of this film to Jia Zhangke’s oeuvre (to cite only one example of its influence among many) immediately becomes apparent through the title of an essay that I haven’t read — Jie Li’s “Home and Nation Amid the Rubble: Fei Mu’s Spring in a Small Town and Jia Zhangke’s Still Life”* -– and a wonderful interview with the film’s lead actress, Wei Wei, about the film, its director, and her costar, Wei Li, in I Wish I Knew, conducted inside a barber shop in 2009. In any case, it isn’t surprising that I owe my first acquaintance with this film to a Chinese film critic, Stephen Teo, who in the early 1990s sent me an English subtitled VHS copy taken from the multicultural, state-run Australian television channel SBS.

Traditionally, history in China is something that belongs to the Emperor — or to his latter-day equivalents or substitutes, starting with Mao –- and perhaps the same can be said about traditional and classical Chinese art. So it isn’t surprising that a perpetual yearning for a lost past can be felt in much of Chinese art cinema, whether it comes from Taipei (Hou Hsiao-hsien’s City of Sadness, Edward Yang’s A Brighter Summer Day, Tsai Ming-liang’s Goodbye, Dragon Inn), Shanghai (Stanley Kwan’s Ruan Linyu aka Actress aka Center Stage, where Fei Mu figures as a character), Hong Kong (Wong Kar-wai’s Days of Being Wild and In the Mood for Love ), Fenyang (Jia Zhangke’s Platform), Pingyao (Zhang Yimou’s Raise the Red Lantern), or Beijing (Li Shaohong’s Blush, Chen Kaige’s Farewell My Concubine, Tian Zhuangzhuang’s The Blue Kite) — to sketch a list of masterpieces that is by no means exhaustive. Indeed, given the sheer breadth of both Chinese art and history as displayed in Taipei’s National Palace Museum — whose ground floor, devoted to world history, with many spacious rooms to traverse before Western history can even make a start — the degree to which they accompany one another in both cinema and film history seems only logical. And one can’t overlook that the most salient Chinese art films set in the present—another set of masterpieces encompassing most features of Jia Zhangke, Peter Chan’s Comrades, Almost a Love Story, Wong Kar-wai’s Happy Together, and, indeed, Fei Mu’s Spring in a Small Town — are above all efforts to historicize the present. For this reason, the conventional nostalgia expressed in Wong’s In the Mood for Love seems to owe a great deal to Wong’s nostalgia for Fei Mu’s masterpiece and its own “nostalgia for the present”, which subsequently becomes the more conventional nostalgia of the film’s Chinese viewers many years later.

To start with the film’s puzzling, contradictory narrative viewpoint, it opens with the voiceover of its heroine, Yuwen (Wei Wei), a young wife whom we see walking along a broken wall, away from a nearby small town that we will never see, despite the film’s deceptive title, which like much of the film seems to offer an unfulfilled promise, a sexual tease. “Please bear in mind the following words,” this actress recalls Fei Mu saying to her in I Wish I Knew. “The most passionate emotions are those most held in check” –-a statement that could serve as the film’s motto as well as my own while reseeing the film and writing this text, with consequences that are both voluptuous and torturous, beautiful and feverish. Wei Wei also says that the director encouraged her to entice her romantically inexperienced costar Li Wei to fall in love with her, a task she says she carried out all too well when he followed her back to Shanghai after the shooting.

Yuwen’s narration is both personal (she explains she likes to walk after her shopping, and is carrying vegetables and medicine in her basket) and uncannily omniscient (she goes on to describe — and the images corroborate — exactly what the three other members of her household are doing in her absence): the aged male servant Huang (Cui Chaoming), whose daily chores we follow, beginning with him emptying his master’s medicine dregs outside the back gate, until he finally locates him, Liyan (Yu Shi), and then Liyan’s teenage sister Xiu (Zhang Hongmei).

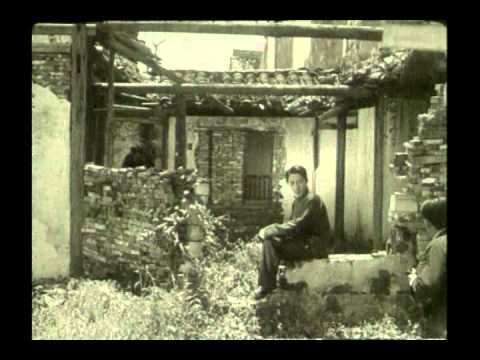

This is after eight years of war with Japan -– the largest Asian war of the 20th century, said to have had as many as twenty million Chinese civilian casualties — and we see the house is in scattered ruins. Each character is viewed alone in a different part of this disarray, as if associated with a separate wound that echoes their emotional state. And the various camera movements introducing us to these characters often seem to blend subjectivity and omniscience, like Yuwen’s offscreen voice, albeit expressing some moods and longings more directly than she can allow herself to do. (Her teenage sister-in-law has an easier time venting her emotions, maybe in part because this is expected of adolescents, but of course Yuwen was an adolescent herself when her romantic feelings were first aroused.)

After Huang knocks on Liyan’s door and discovers he isn’t there, Yuwen interjects, “Liyan doesn’t see me more than twice a day….I leave in the morning to buy groceries. He goes into the garden, where no one can find him. He says he has tuberculosis, but I think it’s neurosis.” A sudden rightward pan across a broken wall that suggests a Miles Davis flourish discovers Huang again, who in turn discovers Liyan through a gap in the wall as she says in her voiceover, “I’m afraid to die, but he seems afraid to live.” (As we will learn, their marriage has already lasted eight years, like the war, producing its own sense of ruins.) Then the camera, instead of following Huang as he hands his master a scarf, reaches Liyan by moving through a separate gap in the wall. This recalls the camera’s impulsive, impatient detour in Sunrise away from the hero and through a dense thicket towards the City Woman he’s meeting by the lake, thus arriving at his destination before he does. And after Liyan asks if his kid sister has left for school yet, there is a cut to the camera approaching her window just in time for her to open and then appear in it, imposing another form of predestination fueled by desire. Yuwen proceeds to tell us over her sister-in-law’s animated movements that she’s nothing like her brother.

The oddly layered effect of this contradictory mix of subjectivity and omniscience is intensified by the names of the actors playing these characters, each name appearing onscreen shortly after each character is introduced, and the musical precision with which these intertitles appear alerts us to the film’s immaculate découpage. Like Yuen’s offscreen voice, it tells us that everything we see and hear can be made to signify at least two things at once. This is arguably also the principle of the mise en scène, including the camera’s exploratory dances, playful or distraught, around each of the characters, which are more like Coltrane’s cascading scales than Davis’ broken fragments. Even so, this is very much a film of absences: a massive unseen war, a buried past, passions held perpetually in check (and thus teetering on the edge of madness and/or violence).

For me, the fatal flaw of Tian Zhuangzhuang’s 2002 remake of Fei Mu’s masterpiece is its exclusion of Yuwen’s voiceover. Treating this element as inessential is for me as drastic a mistake as treating the characters Lockwood and his housekeeper Nelly Dean in Wuthering Heights as unnecessary narrative filters in conveying the story and the explosive passions of Heathcliff and Cathy, a mistake lamentably made by Wyler, Buñuel, and Rivette in their separate adaptations. Yet in the case of Emily Bronte’s novel, this is for the opposite reason. It’s an error to eliminate the incomprehension of the aptly named Lockwood and his maid because we are called upon to imagine and thus furnish the missing outbursts and rages that these two characters plainly lack. But it’s also a mistake to leave out an all-knowing narrative voice that perceives action both globally and personally, as Yuwen’s voice does, because her bifocal vision allows us to view a stifled love story as part of a wider world –- that is to say, historically — which ultimately means inside China as a complex and abstract sociopolitical entity. Indeed, it’s the interaction between these two vantage points, at once “impossible” yet “necessary”, that traces and determines much of the tightly unwinding poetry of the mise en scène. And the “message” of this poetry is Ezra Pound’s:

sky’s clear

night’s sea

green of the mountain pool

shone from the unmasked eyes in half-mask’s space.

What thou lovest well remains,

the rest is dross

What thou lov’st well shall not be reft from thee

What thou lov’st well is thy true heritage

Whose world, or mine or theirs

or is it of none?

***

Beginning with a suite of leftward pans behind the opening credits, punctuated by an upward tilt, Fei Mu’s camera offers a loving commentary even more than Yuwen’s offscreen voice — settling appreciatively, for instance, on a blooming plant as if to illustrate the “spring” of the title, if not the town. And to confound our sense of a linear narrative, he inserts at the end of this prologue, over the director’s credit, a shot of three indistinct figures instead of Yuwen walking down the same path — a shot that we later discover is a radical flash-forward, recurring shortly before the film’s end and including the pivotal fifth and final character, Zhang (Li Wei) — a doctor from Shanghai who arrives to visit his old friend Liyan, not realizing that he is now married to his former lover Yuwen — accompanied here by Yuwen’s young sister-in-law and the family servant.

Significantly, even before this doctor has been introduced, we see him leaving –- another form of predestination that ends the story before it can begin. Questioning, in effect, who or what this story finally belongs to -– ”Whose world, or mine or theirs/or is it of none?” –- is another way of asking if the characters’ ethical decisions are free or predetermined, whether they are, as adults,“free” to gratify their aching adolescent desires. And does the future belong to them, or to an abstraction known as China? Paradoxically, it seems to belong to both — like the absent small town that Yuwen seems to be pointing at in the final shot. Society appears to be absent throughout this film, but one is also made to feel that it determines everything.

Before the doctor’s unexpected arrival, there is a guarded dialogue between Yuwen and Liyan, after he throws away the medicine she’s bought for him and she retrieves it. Enraged by his sense of failures as a husband and that she instead of their servant fetches his medicine, he wonders whether they should separate. She walks off to her room, refusing a discussion while meanwhile resuming her voiceover as she carries her needlework to her sister-in-law’s room. (Is this avoidance of a confrontation grown-up or childish? The film doesn’t say.) Over a shot of the doctor approaching the camera on a road with his luggage, she reflects, “Who could have known that someone would come?” — another moment of omniscience, because this clearly isn’t a point-of-view shot. She continues, “He came from the train station. He walked through the city gate,” just as we (but not she) see that he’s about to do so. “I had no idea that he would come. How does he know that I live here?” Then, after a printed title identifies the character, his narrative function, and the actor playing him (“Zhang Zhichen ‘The Guest’ — Li Wei”) as we see him approach the property’s back gate, her omniscience becomes even more blatant: “He recognizes the back gate to the house. He stops. He steps through the medicine dregs. That’s right, he studied medicine….He knocks on the door but no one hears him. “ (Zhang is the film’s only character who sports Western dress, including a noirish trench coat in this scene, marking him as a seductive outsider and, perhaps more implicitly, a social activist.) After a cut from Zhang to Liyan sitting on a hill amidst rubble, “He knows his way around Liyan’s house so well, he goes around the lane and into the back garden.,,,He even calls out Liyan’s name. I didn’t know that he was Liyan’s friend as well. He climbs through the wall of the flower garden.” This is a very literary form of omniscience, and assigning it to a physically absent Yuwen creates an eerie effect -– a feminized Voice of God attached to a very human and vulnerable character. And perhaps the uncanniest effect of all is the ease with which we can accept this anomaly.

Having led us to this warm reunion of old friends — subsequently joined by the old servant, who also remembers Zhang from prewar days –- Yuwen resumes her narration in order to chart her dawning realization that the visitor, a former classmate of her husband, is in fact her former lover, which she last saw at age sixteen. Once she recognizes this fact, the major issue becomes what she and Zhang will do or not do. In this case, “historizing” the present means coming to terms in some fashion with the past. All we know at first is that she regards it as a vexing problem rather than an opportunity; only later does Zhang become the focus of her present desires. Zhang at once recognizes her and explains to Liyen that they used to be neighbors; their status as former “lovers” (who presumably never had sex) is kept a secret, but Liyan gradually intuits it, as does his sister, and it continues to serve as a vital subtext to all the scenes that follow. The very fact that he’s authoritative about his medical advice also seems to qualify him as a kind of savior to everyone else, potentially freeing them all from their various personal traps.

The camera focusing initially on Yuwen’s feet as she brings Zhang water in his guest room may evoke Bresson, just as the lack of eye contact between them (apart from a couple of quick, furtive glances) evokes Gertrud, but these resemblances belong to the future of cinema; this film’s mastery of indirection is entirely its own. Yuwen insists on treating Zhang as an honored guest and solicits his candor only when it comes to her husband’s health. (She learns that he’ll recover from his tuberculosis, but that he also has a weak heart.) Two cutaway shots of Liyan asleep in his own room only further spells out their unspoken tension, which culminates in her silent tears.

The remainder of the doctor’s visit is mostly uneventful yet rich with piercing erotic inflections. It is further complicated by Xiu’s exuberance and her growing infatuation with Zhang, which tells us as much about Yuwen’s feelings for him at the same age as any flashback would. This leads Liyan to ask Yuwen to become a matchmaker between them (projecting a possible marriage once she turns eighteen), and also by Liyan’s rekindled sexual feelings for his wife and his awareness of Yuwen’s happiness caused by Zhang’s visit, which eventually leads to his suicide attempt. Thus the “spring” of the film’s title alludes to the erotic stirrings of all four characters, at once implicit and omnipresent in both the performances and the mise en scene.

The morning after the doctor’s arrival, he and the three family members go for a walk; when Yuwen joins the others after walking behind them, Zhang briefly takes and squeezes her hand, a glancing detail that has a Bressonian impact. Later, on what she calls “the third morning,” he proposes that they walk together to the “old wall” after breakfast to “talk things over” (something she will do in turn several days later). Their dialogue and gestures continue through awkward indirections and indecisions — issues of whether she’s changed since the war, whether he’ll ask her to leave with him, whether he means to ask her, whether they touch one another or not as they walk. Everything becomes conditional, and comparable questions, gestures, disavowals, and retreats recur whenever they’re alone together, always generating suspense.

Zhang announces his departure on the ninth day of his visit, but like everything else, this winds up being postponed. And the film’s second half chronicles more indecision, culminating in Xiu’s raucous and drunken sixteenth birthday party and Liyan’s suicide attempt the following morning — a jagged and protracted Miles Davis solo full of broken riffs, with Yuwen and Zhang each becoming aggressive and violent in turn. She storms into his room against his wishes; he lifts her up, changes his mind and sets her down, locks her inside as he leaves; she drives her fist through the door’s glass pane; he rushes back inside, dresses her wound, and passionately kisses her hand; she says “Thank you” and leaves, returning to her own room. All these “explosions” and retreats and those that follow occur late at night, in darkness, after the town’s electricity has been shut off, glancingly illuminated by flickering candlelight that provides as much of a dance macabre as the camera movements following, embracing, and abandoning the characters in turn. Then Yuwen becomes omniscient again: over shots of Zhang, alone, taking a pill, intercut with her alone in her own room, she says, “He needs to take a sleeping pill. He’s thinking to himself that maybe I will commit suicide. All I have is regret. I want to die. I can no longer face the world. He remembers that Liyan has some sleeping pills.” Each in turn winds up in Liyan’s room, where Zhang says he’ll leave in the morning, despite Liyan’s protests, and Yuwen lies to him about how she injured her hand. In the morning, it isn’t until Huang fails to rouse Liyan that everyone becomes aware of his suicide attempt, and Zhang and Yuwen revive him.

Frankly I’m embarrassed by many of the emotions that this film stirs in me, and one of the reasons why may be that I’m an American. Manny Farber once admitted to me that he never really “survived” the Depression, and like many, perhaps even most Americans, I’m not sure if I ever really “survived” my adolescence, because many of its wounds have never healed, including those that Pound might even ironically call my “true heritage”—what I lov’st well and lost. Spring in a Small Town was made when I was still a toddler, yet even at age 78 many of its emotions still make me want to run and hide, as its haunted and frustrated characters often do, trying to behave properly yet clearly traumatized.

Yuwen is last seen walking by the ruined wall with Liyan, hoping to rebuild her marriage. Unlike Xiu, she hasn’t accompanied Zhang to the train station. But Zhang says he will return next spring, and Xiu says she hopes he’ll be back by the summer — which implies that the conditional tense in which both women live could be extended indefinitely—unsatisfied longings reaching out into infinity, like unresolved chords. There are other musical refrains or rhyme effects—not just two meetings of the former lovers at the city wall, but Yuwen’s infatuation for Zhang at age sixteen before the war anticipating Xiu’s infatuation now. Zhang, like Coltrane, may have temporarily removed the horn from his mouth, but the music, the desire, the ongoing dance of the mise en scène will continue to blaze in his mind and spirit, as it does in ours, in mine, seventy-three years later.

Footnote

*Modern Chinese Literature and Culture, Vol. 21, No. 2 (Fall 2009), 86-125.