From the March 1978 American Film, when Hollis Alpert was still the editor. If memory serves, this was my first contribution to this magazine. I suspect that the not-quite-accurate title wasn’t mine; like American Film and its parent organization, the American Film Institute, its agenda tends to be needlessly and provincially restricted to American industrial product, unlike those of, say, the British Film Institute or the Cinémathèque Française.

One important informational update: David Meeker’s invaluable reference book has more recently been expanded into an even more invaluable online reference tool that can be accessed here. — J.R.

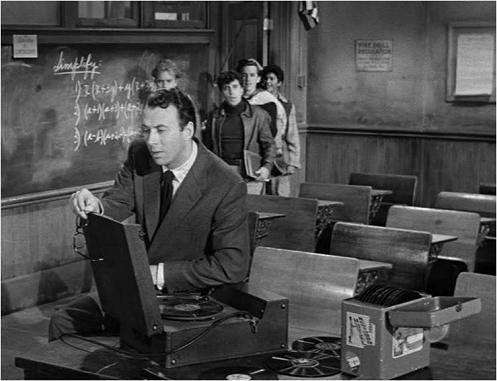

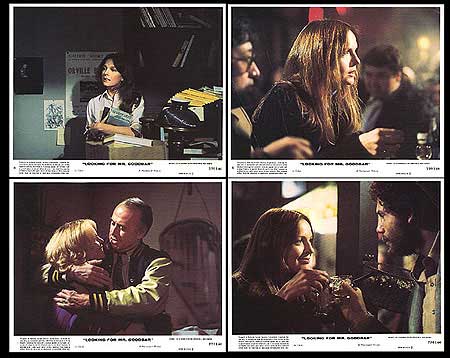

Cuing the audience into the threat of impending violence in Blackboard Jungle (1955) and Looking for Mr. Goodbar (1977), director Richard Brooks has very different aces up his sleeve. In the earlier film, he uses jazz — a blaring, evil-sounding Stan Kenton record. It’s played on a jukebox by Josh (Richard Kiley), a mild-mannered jazz buff and schoolteacher, who is mugged by a gang in an alley while the song is still playing. In the more recent film — where, incidentally, Richard Kiley plays the heroine’s bombastic father — Brooks uses disco singles blasting away in bars, and a strategically placed strobe light. The latter is conveniently given to the Diane Keaton heroine as a Christmas gift, so that we can see her stabbed to death in her flat under its mocking staccato rhythms.

In both cases, the cuing device works as a kind of symbol for the lower depths of dread and paranoia — predicting disaster before it comes, then hyping it full throttle when it arrives. And the fact that Brooks no longer uses jazz to attain this effect may say something about the changing status of jazz in movies since the fifties. It has gone from an expressionist voice of doom in Blackboard Jungle, The Man with the Golden Arm, and Touch of Evil to simply another set of colors within the musical spectrum. Indeed, now that jazz in one form or another can be found in elevators and dentists’ waiting rooms as often as in bars, its implicit meaning in films is hardly the same as it once was.

In Blackboard Jungle, Josh’s taste for jazz makes him a sacrificial lamb, as his rare set of 78s is smashed to bits by his class after he tries to lull them with Bix Beiderbecke’s “Jazz Me Blues”. Five years later, in Brooks’ Elmer Gantry, the public exposure of the hero as a charlatan in momentarily turned into an expressionist witches’ sabbath when a demonic jazz trumpeter appears and bleats his “blue” notes straight into Gantry’s face.

Why does this conceit appear somewhat quaint today? Having been partially reabsorbed in the pop mainstream, jazz is no longer assumed to be automatically synonymous with decadence and the forces of darkness. It can finally be experienced and evaluated on its own terms –just as we may have to wait for the 1990s before we can respond objectively to strobe lights and disco hits.

With this newly acquired freedom, there’s a lot we can do. For one thing, we can begin to look back on the sixty-year partnership of jazz and film with a certain objectivity and we can try to determine why they’ve often behaved together like spiteful siblings. (Both are roughly contemporaneous with the 20th century, having grown out of socially disreputable origins and having fought for serious recognition.) We’re helped in this task by the publication of a big new reference work on the subject — David Meeker’s Jazz in the Movies: A Guide to Jazz Musicians 1917-1977. If we survey the 2,239 films that are described in this catalog (out of which, I should confess, I’ve seen little more than a fifth), we encounter a range of collaborations in shorts and features, fiction films and documentaries which throws a much richer and broader world into relief.

Part of this world, to be sure, is composed of the “jazz film,” a subgenre basically devoted to the recording of performances. But of more interest are the successful collaborations between the expressive possibilities of jazz and film. And of special interest is the fact that the ways in which jazz has been used in movies invariably tells us a great deal about the social, ethnic, aesthetic, and cultural biases of diverse societies and periods. An interesting study, for instance, could be devoted to charting the various responses of film producers to integrated jazz groups in the thirties, forties, and fifties, which would provide a kind of thumbnail social history. Sometimes black musicians were forced to play off-screen while white stand-ins mimed their solos.

If memory serves, the first jazz film I ever saw was a ten-cent “soundie” in an arcade in 1953. Soundies were pint-sized, three-minute movies shown inside the glass bubbles of jukeboxes known as Mills Panoram Machines. According to Meeker, “The films were produced at a rate of five or six per week and featured most of the popular entertainers of the time, usually performing their current record hits.”Among the best are a few jam-packed numbers by Fats Waller, Duke Ellington, Nat “King” Cole (when he was a pianist as well as a singer), and Meade Lux Lewis.

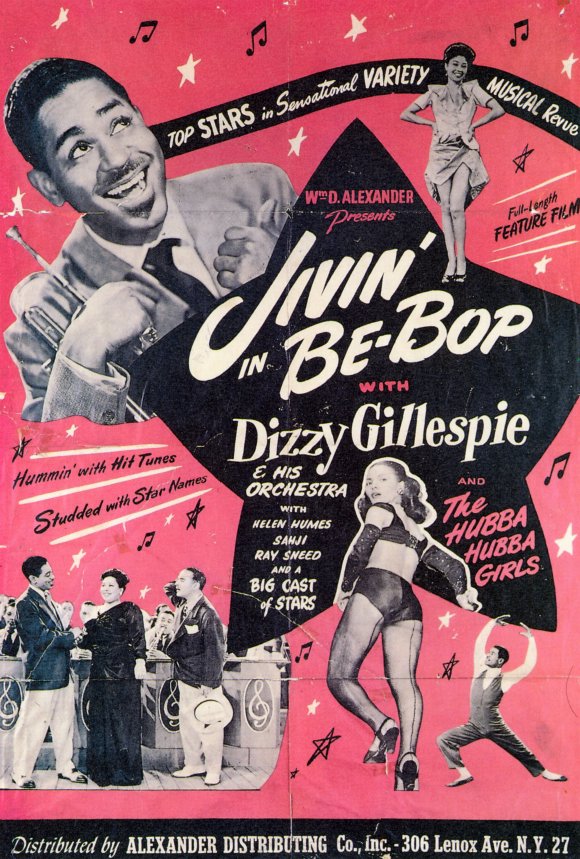

The advantages and drawbacks of such productions roughly match those found in Jivin’ in Be-Bop, a 1947 short feature made for black audiences. It presents Dizzy Gillespie’s big band (including the two main soloists of the future Modern Jazz Quartet, Milt Jackson and John Lewis) with singer Helen Humes interlaced with belly dancers and dull comedians. The sloppy synchronization of music with musicians is often aggravating, yet the pasteboard decor and the drive of some of the tunes make it a fascinating record of the period.

If we want to be scholarly about it, we can say that the first known conjunction of jazz and the fiction film took place in 1917 in The Good for Nothing, a silent comedy which showed the Original Dixieland Band. Rumor has it that Charlie Chaplin, a fan of the group, made a brief and uncredited appearance in this lost film.

Leaping ahead to the sound film, we come upon two remarkable shorts made in 1929 by Dudley Murphy. St. Louis Blues, the better known of these, remains our only film record of the magisterial Bessie Smith. For this reason alone, its hackneyed and rather condescending plot is not so much transcended as obliterated the moment the great singer launches into the title tune. The other short is Black and Tan, which marks the first film appearance of Duke Ellington. It also starts with a comparably dated plot and then works wonders with it. Fredi Washington, a pretty dancer with a heart condition, bribes two piano movers with a bottle of gin so that Duke can continue to rehearse his “Black and Tan Fantasy”. Cut to a nightclub engagement where she insists on dancing a wild, demonic number until she collapses. Dissolve to her deathbed, where Duke’s band and the Hall Johnson Choir — all crowded around her and silhouetted on a far wall — play “Black and Tan” once again at her request. Slow fadeout.

Agee refers to a jam session in Phantom Lady “used as a metaphor for orgasm and death — which in turn become metaphors for the jam session.” I can’t vouch for the accuracy of that, but unquestionably Black and Tan equates death and orgasm with its music in an obsessively eerie way. . The haunting title lament even quotes twice from Chopin’s “Funeral March,” and the voluptuous subjective shots of Fredi hallucinating and later losing consciousness are unmistakably sexual. Compressing vaudeville, “atmosphere,” diverse avant-garde tropes of the twenties, and wonderful music into nineteen minutes, this unlikely gem has seldom been better for making jazz and film do things together that neither could achieve separately.

Thirty years after Black and Tan, Ellington’s score for and brief appearance in Anatomy of a Murder present an equally successful (if much more relaxed) use of jazz as a dramatic device. James Stewart’s hero, a small-town lawyer in Michigan, is a jazz buff who plays a little piano, and the music becomes an extension of his personality as it pervades the film. A similar equation is used in an earlier Otto Preminger film, The Man with the Golden Arm, with Frank Sinatra as an aspiring drummer addicted to heroin and wedded to a bombastic Elmer Bernstein score.

Keeping jazz off-camera often permits its impact to register more subliminally. How many critics have remarked on the effective score of Jean-Luc Godard’s Breathless by Martial Solal, which alternates an elliptical jazz-piano motif for Jean-Paul Belmondo with a lush, parodic chorus of strings for Jean Seberg? The sharp division of the sexes that one invariably finds in Godard is neatly summarized by this musical contrast, and comparable directorial aids can be found in the music of such films as Alfie, Mickey One, No Sun in Venice, and Frantic.

***

Some directors are more adept at using jazz than others, and it’s worth considering some of the reasons why. Improvisation is at the root of jazz, and directors who like to improvise on occasion, such as Robert Altman, seem to have a special feeling for the music. They can be as different as John Cassavetes (in his first too features, Shadows and Too Late Blues) and Howard Hawks. In the movies of Hawks, musical get-togethers between allies always have strong communal functions, and even the nicknames of characters seem to belong to the world of jazz. Only Ball of Fire (1941) and its remake, A Song is Born (1948), use unadulterated jazz explicitly to advance the mood of fellowship in the plot, but the principle is the same in the songfests of Only Angels Have Wings, To Have and Have Not, Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, and Rio Bravo.

The use of a single number in Ball of Fire could serve as a virtual model for how jazz can extend the range of a film. This occurs after about a reel of exposition showing Gary Cooper and six other meek bachelors in a Victorian house at work on an encyclopedia. After Cooper resolves to go out into the world to bolster his impoverished grasp of current slang, we hear big band music over a “montage” sequence showing him collecting phrases all over the city. Then we cut to him in a nightclub, where a slow pan to the right reveals the Gene Krupa orchestra. Barbara Stanwyck (as “Sugarpuss” O’Shea) makes a grand entrance and proceeds to sing “Drum Boogie,” a swinging romp whose infectious beat quickly takes over the place.

Cut off from his scholarly friends, Cooper’s initial response to this collective feeling is acute embarrassment; yet by the end, he’s moving his hands — discreetly but nimbly — to the music. For an encore, “Sugarpuss” and Krupa plant themselves at a nearby table, and Krupa offers a reprise of his drumming with wooden matches on a matchbox while a group of spectators huddles around them. From Victorian parlor to lively club, the transition from one form of coziness to another is remarkably fluid. Spatially as well as rhythmically, the spirited music is permitted to call all the shots.

In contrast, the uses of jazz by several other filmmakers turn the music into a solitary, almost solipsistic kind of pleasure. Altman’s The Long Goodbye begins with Elliott Gould humming and singing snatches of the title tune while Dave Grusin’s off-screen piano trio improvises on the melody in a different key; the overall effect is at once plaintive and unsettling. Two very different — and unjustly neglected — films expand on this notion. In Norman McLaren’s delightful abstract short Begone Dull Care, the lively improvisation of Oscar Peterson’s piano is matched perfectly by McLaren’s improvised doodles, drawn directly onto the film negative. The hero of James B. Harris’s live-action Some Call it Loving is a wealthy baritone sax player who inhabits a strange world where everyone caters to his secret wishes. The music played by his group magically captures the disturbing perfection of his self-contained dreamworld, feeding on its own fantasies.

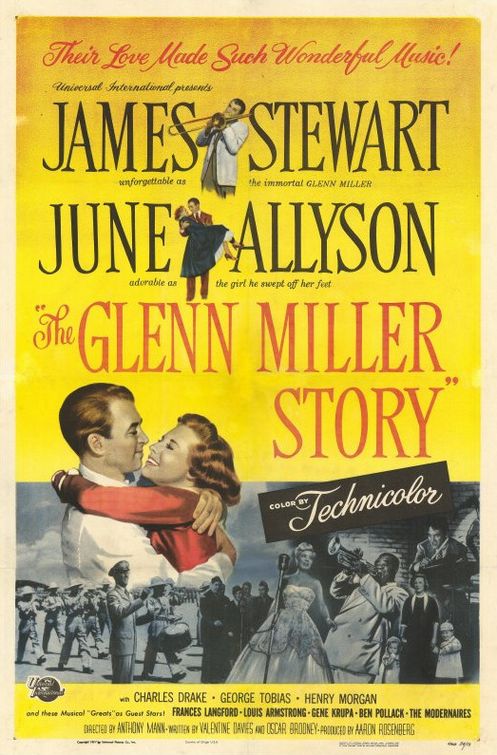

One category, the musical biography, has generally produced mixed results, perhaps because the plots of such movies are usually restricted to sentimental formulas. For some reason, the heyday of this subgenre was the fifties, when Young Man with a Horn, The Glenn Miller Story, The Benny Goodman Story, The Five Pennies, and The Gene Krupa Story all appeared. The most that can be said of these movies is that they occasionally offer worthwhile music along with their saccharine stories, even if the “famous lines” in question are often mangled beyond recognition.

The most recent and notable of encounter of jazz and Hollywood is New York, New York, and if certain details in this film are uncomfortably reminiscent of ones found in musical biographies, it must be quickly added that the movie rises well above them in other respects. The problem here is principally the music rather than the fictional characters – sax player Jimmy Doyle, played by Robert De Niro, and singer Francine Evans, played by Liza Minnelli.

The main difficulty with Doyle’s music in dramatic terms is that it simply isn’t good enough. During both his auditions in the film — at a Brooklyn dive and in a Virginia dance hall– he delivers little more than a string of warmed-over clichés. When we discover much later that his combo’s version of the title tune has hit the top of the charts in Down Beat — right above Charlie Parker’s “Mohawk”! — the required suspension of disbelief is more than any self-respecting jazz fan can manage.

This is not to fault the capabilities of either director Martin Scorsese (whose uses of music elsewhere, in Mean Streets, Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore, and Taxi Driver, is often brilliant) or swing tenor Georgie Auld, who ghosted all of Doyle’s solos. The important point here is that whatever else the film has to offer, most of the jazz elements have been needlessly glossed over, and something gets lost in the shuffle. The tension generated between the two leads in non-musical scenes gets thrown off-balance, because only Francine’s music gets the film’s full attention: Compare her version of the theme song with Doyle’s.

Consequently, it is Liza Minnelli and Diahnne Abbott who convey most of the jazz feeling in the movie. Through a curious alchemy, the jazz becomes Hollywoodized while some of the “Hollywood” numbers are allowed to swing.

Any lessons to be learned from this? Mainly an obvious one — that if New York, New York had better jazz it would have been a better movie. But also a more general one — that the way jazz is used in any film winds up telling us a lot about the people who made it. We discover something about their eyes, their ears, their sense of rhythm and pacing, and their storytelling abilities, not to mention their cultural attitudes. To regard jazz as an expendable or neutral element is to turn one’s back on all the cinematic and dramatic possibilities it has to offer.