From the Chicago Reader (April 26, 2002). — J.R.

The Cat’s Meow

*** (A must-see)

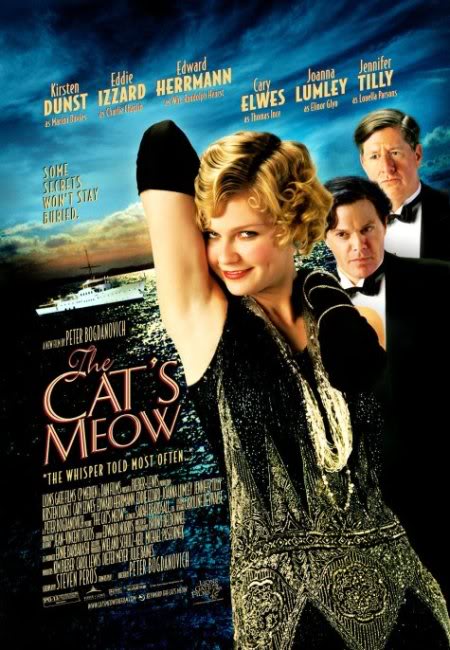

Directed by Peter Bogdanovich

Written by Steven Peros

With Kirsten Dunst, Cary Elwes, Edward Herrmann, Eddie Izzard, Joanna Lumley, Jennifer Tilly, Victor Slezak, James Laurenson, and Claudia Harrison.

ORSON WELLES: In the original script [of Citizen Kane] we had a scene based on a notorious thing Hearst had done, which I still cannot repeat for publication. And I cut it out because I thought it hurt the film and wasn’t in keeping with Kane’s character. If I’d kept it in, I would have had no trouble with Hearst. He wouldn’t have dared admit it was him.

PETER BOGDANOVICH: Did you shoot the scene?

ORSON WELLES: No, I didn’t. I decided against it. If I’d kept it in, I would have bought silence for myself forever. — This Is Orson Welles

I edited This Is Orson Welles, a series of interviews Peter Bogdanovich did with Welles, at the request not of Bogdanovich but of Oja Kodar, Welles’s companion and collaborator for the last 20-odd years of his life, to whom Welles had willed the rights. The incident Welles alluded to in this exchange is the subject of The Cat’s Meow, directed by Bogdanovich and adapted by Steven Peros from his own play.

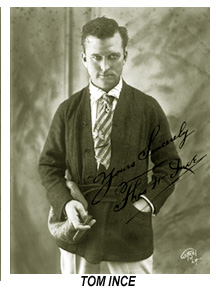

Bogdanovich may see Welles as the inspiration for his film, but I have no idea where Peros got his facts. If you turn to the entry under Thomas Ince — a Hollywood director, screenwriter, and actor who was once famous as a pioneering producer — in the 1979 edition of Ephraim Katz’s Film Encyclopedia you read: “On the night of November 19, 1924, [Ince] was mysteriously and fatally injured aboard William Randolph Hearst’s yacht, on which he had gone for a weekend of fun and frolic with several other distinguished guests. He died before regaining consciousness. The death was officially attributed to heart failure as a result of acute indigestion. But scandalous rumors persisted in Hollywood that Ince was shot by Hearst, who suspected him of carrying on an affair with his protegee, Marion Davies.” A similar story is offered by The Cat’s Meow. Bogdanovich, assuming that most viewers won’t know anything about Ince, has asked reviewers of the film not to reveal what happens on the yacht. I can’t comply with his request because I see no other way of discussing the film in any detail, so you may want to see the film before finishing this review.

Ince’s name doesn’t appear in the index of either Robert Carringer’s The Making of “Citizen Kane” or Ronald Gottesman’s collection Perspectives on “Citizen Kane”, which contains Carringer’s near-definitive essay about the script’s authorship. But Ince’s name does appear in Pauline Kael’s less scholarly but more entertaining “Raising Kane“; her principal source was John Houseman, script supervisor for cowriter Herman Mankiewicz, and it seems safe to conclude, even without her prodding, that some version of the story must have cropped up in Mankiewicz’s first draft of the script, which Welles subsequently edited and added to. According to Kael, the only trace of the subplot left in the script is a speech made by Susan Alexander, who was loosely based on Davies, to the reporter Thompson about Kane: “Look, if you’re smart, you’ll get in touch with Raymond. He’s the butler. You’ll learn a lot from him. He knows where all the bodies are buried.” Kael writes, “It’s an odd, cryptic speech. In the first draft, Raymond literally knew where the bodies were buried: Mankiewicz had dished up a nasty version of the scandal sometimes referred to as the Strange Death of Thomas Ince.”

I don’t think we’re likely ever to know for sure what happened on Hearst’s yacht on November 19, 1924. The value of The Cat’s Meow — whose cryptic title may stem from a feature of the same name produced by Mack Sennett and directed by Roy Del Ruth that was released in 1924 — has more to do with its capacity to get us to reflect on its most famous characters: newspaper tycoon Hearst, his mistress Davies (the principal star of his film company, Cosmopolitan Pictures), producer Ince (the yacht party’s guest of honor, he was belatedly celebrating his 42nd birthday and trying to set up a merger of his film studio with Hearst’s), Ince’s mistress Margaret Livingston (a movie actress who three years later played the Woman From the City in F.W. Murnau’s Sunrise), Charlie Chaplin, gossip columnist Louella Parsons, and British novelist Elinor Glyn (who serves as the movie’s narrator).

The version of events offered by The Cat’s Meow is that Chaplin was having an affair with Davies and that Ince — who helped expose the infidelity to Hearst, hoping to gain his trust and encourage the merger — was shot from behind by Hearst, who’d seen him chatting with Davies and mistaken him for Chaplin. Some if not all of this hypothesis is supported by David Robinson’s authorized biography of Chaplin, which notes that a gossip item in the November 16 New York Daily News (which figures prominently in the film) implied that Chaplin and Davies may have been having an affair, confirms that Hearst kept a gun on the yacht for shooting seagulls (another detail used in the film), and adds that Ince was a small man whose head and hair color were similar to Chaplin’s and who might well have resembled him from behind. But Robinson also reports that “there is great doubt as to whether or not [Livingston] was aboard” and that “Chaplin consistently declared to his intimates that he was not aboard the yacht,” though photographs do show him at Ince’s cremation two days later. Robinson further notes that Glyn told Eleanor Boardman, King Vidor’s wife at the time, “that everyone aboard the yacht had been sworn to secrecy, which would hardly have seemed necessary if poor Ince had died of natural causes.”

The strongest achievement of The Cat’s Meow may be the performances, especially those of Kirsten Dunst (Davies), Edward Herrmann (Hearst), and even Eddie Izzard (Chaplin), who takes some getting used to because, as other reviewers have noted, he bears a closer resemblance to Welles in his mid-30s than to Chaplin at the same age (Welles was only nine in 1924). This resemblance is surely deliberate on Bogdanovich’s part; he knew Welles much better than Chaplin and probably saw parallels between them. (Given Bogdanovich’s apparent identification with both figures, particularly insofar as he’s a controversial Hollywood filmmaker with a bumpy career and a ladies’ man who’s been both envied and hated, one might even hypothesize that his depiction of Chaplin adds up to a covert yet scathing autocritique — though it would seem outrageously arrogant if he dared own up to it.) If we can overlook Izzard’s lack of physical resemblance to Chaplin, his capacity to suggest Chaplin’s essence in other ways — more as a man than an artist — steadily grows as the film develops. (Similarly, Bogdanovich is more attentive to Hearst as a man than he is to Hearst as a public figure — and I would think that his own marriage to a woman much younger than himself bolstered his identification with Hearst.)

In some ways, Dunst gives the film’s most impressive performance. She’s only a teenager, but she succeeds in embodying Hearst’s flighty if mainly loyal 27-year-old mistress to an uncanny degree. Herrmann’s portrayal of Hearst is equally sympathetic and multilayered, though quite unlike Welles’s Kane version, as there’s virtually no social or psychological critique of him. (The only time I noticed Bogdanovich alluding to Kane directly was when he showed Hearst on a rampage after receiving confirmation of Davies’s affair with Chaplin.) This may be because romantic relationships typically count for everything with Bogdanovich and social concerns for practically nothing — despite a self-conscious little speech by Glyn in the film that zeroes in on the “California curse” she associates with Hollywood, in which “your hold on morality…vanishes without a trace.” Hearst’s devotion to Davies winds up excusing not only his pleasure in shooting seagulls, but his corruptness as a press baron and yellow journalist, in which the film takes no interest. The only people singled out for any sustained critical or satirical abuse are Louella Parsons (Jennifer Tilly) and a straitlaced, middle-aged midwestern couple. By contrast, the treatment of Hearst, Davies, and Chaplin is so multifaceted I was eventually persuaded to overlook some of the more brazen improbabilities, including the notion that Davies would have been so open about her relationship to Chaplin in such close proximity to Hearst.

Cary Elwes, a dead ringer for Ince, may well deserve as much praise as Dunst, Herrmann, and Izzard. Perhaps I’ve been ignoring him because he plays a real-life celebrity I know less about and find less sympathetic than the other three central characters. His colleagues in the film, notably Hearst, perceive him as a has-been, and he winds up desperately tattling on Chaplin and Davies in his efforts to maneuver himself back into the limelight — which may make him more of a self-critical projection for Bogdanovich than either Chaplin or Hearst.

Though The Cat’s Meow is set eight years earlier than Robert Altman’s Gosford Park and in the U.S. rather than in England, and though it features a much racier crowd (pun intended when it comes to a late-night group grope with a black saxophone player), the two films do have a few loose parallels, especially in their parodic treatment of Parsons and their satiric critique of the way servants are exploited (the resemblances between Joanna Lumley and Maggie Smith are mainly superficial). Yet the differences between the films are as instructive as the resemblances. The convincing portrayal of Parsons as stridently and unconsciously gauche seems Altman-esque, but once she finds a way to bribe Hearst into giving her a lifetime contract, Bogdanovich drops the caricature and shows her to be much more clever than previously suggested. A Ping-Pong game that has a couple of maids scurrying after countless balls as they’re heedlessly batted off the table by two guests condenses most of the best gags in Gosford Park, but the sequence is offhand, the point forgotten almost as quickly as one of the balls.

What’s masterful about Bogdanovich’s direction is the cumulative detail, which adds complexity to incidental as well as central characters. He has a graceful way of switching viewpoints from one character to another and an uninsistent yet mainly persuasive sense of period. He even presents a plausible version of Hearst’s taste. I remember being surprised when I visited Hearst’s mansion, San Simeon, in the 80s at how tasteful rather than vulgar much of it was; that was one of the main details Citizen Kane changed, undoubtedly for good reasons.

Because Kane did such a good job of mythologizing both Hearst and Welles — albeit in very different ways, for very different reasons — and because the film has become an unassailable classic in many people’s minds rather than a marvelous aberration, it has created a lot of unhelpful and misleading impressions. Perhaps the cardinal failing of The Battle Over “Citizen Kane”, a 1996 Oscar-nominated documentary, is its nearly groundless argument that Hearst and Welles had a lot of things in common. The corruption of the former and the innocence of the latter only begin to describe the essential differences. Indeed, I would argue that it’s precisely because Kane is the only Welles film to view corruption from a corrupted viewpoint — the pivotal contribution of Mankiewicz, a gifted Hollywood hack — that Hollywood ultimately warmed to the film, even assigning the script an Oscar.

Charles Foster Kane, people are fond of saying, predicts in his decline the subsequent decline of Welles, but I think this is a misguided assumption. If any Welles character can be said to predict what eventually happened to Welles, it’s George Minafer, the spoiled and arrogant rich kid of The Magnificent Ambersons, Welles’s second feature. Welles refused to play the character himself (after a clumsy effort to do so in the radio version), casting Tim Holt in the part; but he clearly identified with Minafer — and no doubt identified with him more when he, like Minafer, lost his wealth and power.

Minafer winds up learning humility the hard way, though hardly anyone in his family or circle is left to notice when he does. One might say a similar lesson has been learned by Bogdanovich, who in some respects has followed Minafer’s trajectory more than Welles. After all, Welles’s only substantial commercial successes were in radio and theater; Bogdanovich became a millionaire after directing three successive hits in Hollywood. But then Bogdanovich became a much-reviled has-been. He has had more opportunities for work than Welles, but his public profile has shrunk more. His hard-won humility may well have made him a better director, though few people noticed that Texasville (1990) was better directed than The Last Picture Show (1971), thanks to his diminished reputation in the film industry.

“Peter Bogdanovich returns to filmmaking,” reads the headline over Tad Friend’s story in the April 8 New Yorker, but of course he never really left. He was just banished to the purgatory of TV movies, an uncharted territory that doesn’t qualify as “filmmaking” as the New Yorker understands it. Friend’s entertaining profile of Bogdanovich points out that The Cat’s Meow is certainly a lesson in humility and modesty as far as production circumstances are concerned: it was shot in 31 days in Germany and Greece for $6 million, though it looks more polished than many Hollywood features costing ten times as much. In these terms, this picture might well be considered a more impressive accomplishment than many of his early pictures. But it speaks with a quieter voice, and what it says seems substantially more personal and thoughtful.