From the August 8, 2003 issue of the Chicago Reader. — J.R.

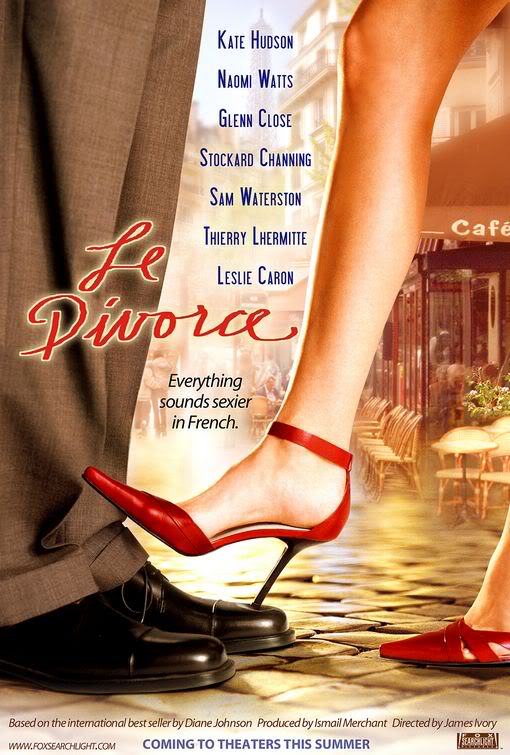

Le Divorce

*** (A must-see)

Directed by James Ivory

Written by Ruth Prawer Jhabvala and Ivory

With Kate Hudson, Naomi Watts, Thierry Lhermitte, Leslie Caron, Melvil Poupaud, Glenn Close, Stockard Channing, Sam Waterston, Matthew Modine, Jean-Marc Barr, Nathalie Richard, Bebe Neuwirth, and Stephen Fry.

Producer Ismail Merchant, director James Ivory, and their regular screenwriter-adapter Ruth Prawer Jhabvala seem to have a special affinity for Americans in Paris, the subject of three of their five most recent films — Jefferson in Paris (1995), A Soldier’s Daughter Never Cries (1998), and now Le Divorce. The first of these is one of their worst features, while the second and third are among their best. So their special affinity doesn’t seem to matter as much as the quality of their material and their particular feeling for it. In the case of Le Divorce, their fidelity to the civilized attitudes of Diane Johnson’s novel makes this one of their most sophisticated and entertaining features to date.

The novel is narrated by Isabel, a 19-year-old film-school dropout from Santa Barbara who’s gone to Paris to visit her older stepsister Roxy, a poet married to a French painter and pregnant with their second child. The story focuses on the complications that ensue when Roxy’s husband, Charles-Henri, leaves her for another woman the day before Isabel arrives, including the intricate divorce proceedings and a protracted dispute about the ownership of an anonymous 17th-century French painting of Saint Ursula. It also focuses on the much simpler complications that ensue when Isabel gleefully becomes the mistress of Charles-Henri’s brother Edgar — a 70-year-old TV pundit and former state minister who argues for French intervention on behalf of Bosnian Muslims — while keeping a younger French boyfriend she isn’t serious about in reserve.

As Johnson has pointed out in interviews, Isabel is a deliberate update of a Henry James heroine — a plucky, single American woman, like Isabel Archer or Daisy Miller, who’s loose on the continent — and part of her witty point is that sexual and cultural norms have changed enough that an update is required. In some respects, her Isabel is as righteously innocent as James’s, but in other respects, including some of her attitudes about sex, she may be ahead of both her French lovers. Her practicality and ethics counterpoint those of Charles-Henri and his relatives, but Johnson is far too sophisticated and smart to see these motives as being in competition.

The movie arrives at a time when cultural understanding between American and French people appears to have reached an all-time low. The evenhanded and intelligent respect and amusement Johnson clearly feels for both cultures offers an exhilarating alternative to yahoo American conceits like “freedom fries” and the equally pernicious French assumption that most Americans think like our president.

There is one deranged and rather unpleasant American in Johnson’s upper-crust universe — Tellman, an entertainment lawyer who’s the grief-stricken husband of Charles-Henri’s lover — but he’s so marginal to most of the action he can’t be said to belong to that universe (which is surely why he’s ejected from a literary reading when he raises a minor ruckus). He’s so out of place, in fact, that he’s never entirely believable; neither Johnson nor Merchant-Ivory-Jhabvala knows quite what to do with him — or what to make of him — except use him as a piece of stage machinery.

The filmmakers are on much firmer ground when it comes to Roxy (Naomi Watts); to Olivia Pace, a wise and famous American author who’s a fair facsimile of Mary McCarthy (Glenn Close is clearly having a fine time playing her); and to a very English art appraiser from Christie’s (played with even greater relish by Stephen Fry). They’re so confident with these types that they can even give them witty lines that aren’t in the novel but are fully in character: Fry may get the film’s biggest laugh when he responds to the observation that a million pounds is a lot of money by saying, “Yes, to some people I suppose it is.”

Most of the major differences between the novel and the movie — apart from the distinctions that exist between reflection and spectacle — are the result of the streamlining most novels get when they’re adapted cinematically. I don’t recall Isabel’s age being given in the film, but Kate Hudson, the 24-year-old who plays her, definitely seems older than 19, and Thierry Lhermitte, who plays “Oncle Edgar,” seems considerably younger than 70. Isabel is now the sister rather than the stepsister of Roxy, and Charles-Henri leaves Roxy at the precise moment Isabel turns up at their Paris flat, so that he can conveniently take the taxi she’s getting out of.

In a similar spirit of streamlining — which often simply means making details more immediately legible or symmetrical — the woman Charles-Henri runs off with is Russian rather than Czech, Roxy is given a potential replacement for her estranged husband, and Edgar’s habit of giving the same expensive Hermes purse to his successive young mistresses is extended so that another of the story’s more prominent characters becomes a former recipient. A much more consequential, and lamentable, change — shifting the location of a suspenseful, melodramatic climax involving Tellman (Matthew Modine) from Sleeping Beauty’s tower in EuroDisney to the Eiffel Tower — can perhaps be attributed to problems with Disney, though it’s also possible that the use of a stereotypical tourist attraction was more than the filmmakers could resist. (Either way it’s a pity, because Johnson scores some of her best hits with the EuroDisney setting.)

And consider how the following paragraph gets adapted: “I learned… that if you drink a little tisane of orange and rosewater or mint, it perfumes your own juices. I feel I never would have found that out in Santa Barbara. I learned this French erotic secret from Janet Hollingsworth [an American friend], with whom Roxy and I had coffee one afternoon. ‘I’ve ferreted out a good one,’ she said. ‘Did you know that…?’ Quite a lot of tisane, though — a whole teapotful is required, she said.”

In the movie this “French erotic secret” is imparted by Edgar and promptly put into practice by Isabel — which, like all my other examples, suggests that the major function of adaptation is to make both the story and its details as consumerist as possible. And consumerism is the major calling card of Merchant-Ivory-Jhabvala literary adaptations and their many imitations. “I’d love that for my living room” or “I’d love to try that out with my husband/boyfriend” seems to be the desired response.

Several years ago this glossy form of art cinema seemed to be all the Fine Arts movie complex on South Michigan was willing to show on a regular basis. I sometimes felt that this House & Garden, Vanity Fair, or Gourmet (or in the case of The Wings of the Dove, Playboy) cinema — nearly always in English and directed chiefly at yuppies — was crowding out every other kind of art cinema, especially the kind that offered glimpses into cultures different from our own.

Happily, the situation is better now, with commercial venues such as Landmark’s Century Centre offering more varied choices. Yet even though Merchant-Ivory-Jhabvala cinema is still consumerist, Le Divorce gives a few glimpses into contemporary French cinema through the casting alone: Melvil Poupaud, who plays Charles-Henri, is a Raul Ruiz discovery and regular, and Nathalie Richard, who plays one of Charles-Henri’s relatives and was also in A Soldier’s Daughter Never Cries, has worked with Jacques Rivette and Olivier Assayas.

Much of the time this film is clearly transporting us into an upper-class wet dream while periodically tossing off wry jokes about what it’s doing, but (as with Fry’s remark quoted above) it’s a little too affectionate to qualify as satire in the usual sense. The novel, which isn’t consumerist to the same degree, comes a little closer, as when Isabel makes the following observation about Edgar’s use of the word “amuse” after he proposes that she become his mistress: “I thought ‘amuse’ sounded condescending, as in ‘amusing little trifle,’ but I had already discovered that words in French have a different intensity, less or more. Je le deteste, they say, meaning, I mildly dislike it; je l’adore means it’s okay. If something is really great you have to say it’s not bad, pas mal. Also you have to use the words suitable for your station in life. If not, people gasp and laugh.”

This is light satire that cuts two ways — ribbing both the French taste for hyperbole and the American dismay when confronted with it (which shows a less lofty hyperbole of its own). For me, the best reason to see this movie is that in the midst of her amusement Johnson feels sympathy and admiration for both cultures, and for all its glitz, the adaptation preserves and extends the same sentiments.