From the Chicago Reader (May 15, 1992). — J.R.

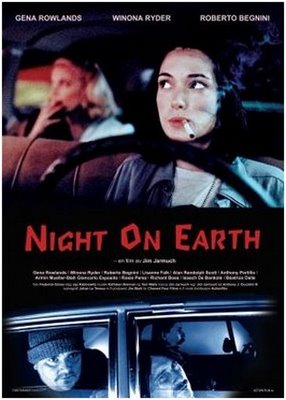

NIGHT ON EARTH

** (Worth seeing)

Directed and written by Jim Jarmusch

With Winona Ryder, Gena Rowlands, Giancarlo Esposito, Armin Mueller-Stahl, Rosie Perez, Isaach de Bankolé, Beatrice Dalle, Roberto Benigni, and Matti Pellonpaa.

As the most popular American independent filmmaker around, Jim Jarmusch carries a special burden: his reputation makes his work particularly hard to evaluate. Other American independents who haven’t enjoyed his commercial success — he’s the only independent who comes to mind who works mainly in 35-millimeter and owns all his own pictures — envy and even resent him, questioning whether he offers a serious alternative to the commercial mainstream. Indeed, Jarmusch has come to be so identified with artistic freedom that it’s difficult to see how any of his movies can live up to his reputation.

“Jim Jarmusch’s planet is the Lower East Side,” began Karen Schoemer in an awestruck feature in the New York Times late last month. “Its bars, its bodegas and its pavement make up his home, his office and his hangout.” “The director finds drama in the ordinary” reads a pull quote in the following hagiography, and clearly so does the Times: it finds a special magic and potency in a run-down neighborhood simply because Jarmusch lives there. Much as the recent riots in LA demonstrated that the only way to bring serious media attention to a ghetto nowadays is to set it on fire, Schoemer’s story shows that one of the best ways to get the Lower East Side into the Times is to photograph and interview Jarmusch there.

Of course this kind of adoration has nothing to do with the quality of Night on Earth, Jarmusch’s mainly masterful and charming yet doggedly modest fifth feature, but it does tell us something about the expectations greeting it. Sergey Diaghilev’s famous instruction to Jean Cocteau was “Astonish me!” But it appears that many viewers’ implicit message to Jarmusch is “Remind me,” or to paraphrase Rick in Casablanca, “Play it again, Jim.” Jarmusch is mainly honored and rewarded to the extent that he turns out familiar goods (attitude as style, star as icon, road as the world) rather than assumes any risks. The paradoxical upshot is that our most photogenic representative of artistic independence and freedom is often rewarded for doing the same things over and over again.

Jarmusch himself seems acutely aware of this paradox, and in some ways Night on Earth is designed to break free of these repetitions. But it also either breeds or trades on other routines that are every bit as shopworn by now as those underlying Stranger Than Paradise, Down by Law, and Mystery Train, his three previous 35-millimeter features, though they may be familiar in more mainstream ways: Night on Earth employs more dialogue and close-ups and cutting, more Hollywood casting and pacing. But however you look at it Night on Earth is as much a product of New York minimalism as any of Jarmusch’s features from Permanent Vacation on, and nearly all its strengths and limitations derive from this fact.

Composed of five sketches, each of which runs for about 25 minutes and is played in the language of the city it’s set in, Night on Earth focuses on the interactions between taxi drivers and their passengers during rides taking place simultaneously in Los Angeles, New York, Paris, Rome, and Helsinki. These five cities occupy four time zones, and the film emphasizes this global relativity at the outset by beginning in outer space and approaching earth spinning in its orbit. After the camera penetrates the atmosphere it glides over a global map, and this transition from the cosmic (the solar system) to toylike banality (an obviously man-made globe) perfectly encapsulates Jarmusch’s ironic angle of vision throughout. Indeed, relativity is the principal theme of the existential encounters between strangers in all five of the movie’s episodes.

Jarmusch cuts to a row of five clocks, each labeled according to city; after centering on the LA clock, which is set at 7:07 PM, he cuts to a camera movement approaching LA on a map as a light goes on beside its name. The didactic simplicity of this device, used to introduce all five episodes, may suggest — as independent filmmaker Jon Jost has sarcastically noted — that Jarmusch is employing minimalism at a first-grade level, aiming his movie at dimwits. But the device also functions rhythmically like a musical refrain, giving the viewer a chance to breathe between episodes while briefly reestablishing the mock-cosmic vantage point.

There’s an interesting development in the five sketches as the film moves from dusk in LA to dawn in Helsinki; death becomes a central factor in the last two episodes, for instance, and the overall tone grows darker as the movie drifts eastward toward daybreak. But there are also certain recurring motifs and internal rhymes that suggest songlike refrains rather than development, such as the sunglasses worn at night by the drivers in LA and Rome and the related issue of blindness informing the Parisian episode, or the immigrant cabbies in the New York and Paris sections who drive terribly.

Each sketch begins with a few shots that evoke the urban setting, then generally we’re introduced to the driver before we encounter the featured passenger. (Only the New York sequence begins with the passenger instead.) In LA, we intercut between a punky driver (Winona Ryder) ferrying two spaced-out males to the airport and a middle-aged casting agent (Gena Rowlands) emerging from a small plane and answering a call on her cellular phone. Jarmusch continues to intercut between them before they meet, when the driver lets off her passengers and calls her dispatcher on a pay phone while the agent, waiting for her luggage, phones a client: the two characters confront each other at the precise moment that each mutters “Shit!” to herself.

The central narrative point of this first episode is that the agent wants to cast the driver in a Hollywood movie but discovers that the driver likes driving a cab, wants eventually to become a mechanic like her brothers, and isn’t remotely interested. At first the agent can’t even conceive of such a response; by the end we’re led to suppose that she’s been educated by the encounter. Clearly this episode alludes to Jarmusch’s own refusal to accept any Hollywood offers, and by casting Rowlands, Jarmusch summons up her late husband and principal director, John Cassavetes, another independent filmmaker (though Cassavetes partly financed his films by working as a Hollywood actor). But the chief result of this reference is to make us question whether Jarmusch, unlike Cassavetes, has wound up constructing his own subtle equivalents to Hollywood through his careful commercial considerations, such as the casting itself.

The postmodernist references in the casting throughout Night on Earth suggest a heavy reliance on the tried-and-true — mainly in the dubious form of the “homage.” This serves as Jarmusch’s commercial safety net by guaranteeing various kinds of recognition in the international market while raising the question of whether such references are genuine expressions of artistic freedom or ready-made labels partly designed to conceal strategic flights from that freedom. The LA episode seems constructed to exploit Cassavetes’s aura — even the agent’s destination, Beverly Hills, alludes to the site of the Cassavetes-Rowlands homestead, and the film’s cinematographer, Frederick Elmes, shot two Cassavetes features, The Killing of a Chinese Bookie and Opening Night (in addition to three David Lynch features). But there’s little in the style or content of the sketch that suggests any detailed or meaningful attention to Cassavetes’s work; Jarmusch’s reference to him is like a job reference — an “objective” credential meant to enhance the potential employee’s appeal.

The principal reference in the New York episode (10:07 PM) is Spike Lee, though the presence of Armin Mueller-Stahl as the comically inept driver, a former East German circus clown, may also summon up the late Rainer Werner Fassbinder. The two other actors here, Giancarlo Esposito and Rosie Perez, are veterans of Lee features — both were in Do the Right Thing, and Esposito was in School Daze — and their hyperventilating here obviously evokes their work with Lee. Esposito is initially the passenger, bound for Brooklyn (another Lee reference) from Manhattan, although he quickly takes over the wheel when he discovers that Mueller-Stahl barely knows how to drive; discovering his sister-in-law (Perez) en route, he insists on driving her to Brooklyn as well. The whole episode affectionately lampoons New York brashness: the degree to which New Yorkers express all their emotions, friendly as well as hostile, by yelling at the top of their lungs at each other is part of the comic point (Mueller-Stahl, a relative newcomer to the city, usually just gapes in admiration at the other two). Here Jarmusch tills a field that has already been plowed to some extent by Lee, but the fact that Jarmusch is a New Yorker himself gives this episode a relaxed authority, and of all the sketches this is arguably the most assured and good-natured.

The references in the Paris episode (4:07 AM) are somewhat more obscure — Isaach de Bankolé (the driver) appeared in Claire Denis’ Chocolat, and Beatrice Dalle (the passenger) in Jean-Jacques Beineix’ Betty Blue. But here, at least, the actors are used more for their own sakes than for the auras of the directors alluded to. Perhaps the most subtle of the film’s segments, this one pits an Ivory Coast driver with a chip on his shoulder against a blind, self-assured female passenger who refuses to let herself be victimized by his gestures of pity. This examination of Parisian “armor” and brittleness may be as much a commentary on a particular urban style as the New York episode, and both actors quite effectively spell out their variants on this behavior. What’s relative in this case are the claims of the grouchy African driver and of the defiantly self-reliant blind passenger, who implies that neither of them has anything to feel grouchy about — in contrast to the final episode, in Finland, where the misery the driver recounts makes the troubles of one of his drunken passengers seem trivial.

Roberto Benigni, the Italian comic and writer-director Jarmusch featured in Down by Law, dominates the next episode, set in Rome (4:07 AM). Playing the driver, he sets up a manic nonstop monologue well before he gets around to picking up a passenger, a priest (Paolo Bonacelli) whom he insists on calling a bishop. He also insists on regaling the priest with an obscene confession about sexual acts he committed with a pumpkin, a sheep, and his brother’s wife, and although the priest suffers a heart attack midway through, Benigni blithely keeps on talking, never turning around to notice the fact. (Just as the overall friendliness between driver and passenger in New York rhymes with the comparable mood in LA, the heartlessness and insensitivity on display here partly match the mood in Paris.)

The filmmaker being “celebrated” in the Rome episode is Benigni himself and his blasphemous performances, though the comic’s tendency to work alone creates a rather creepy ambiguity here. We never really know whether the priest’s heart attack is the result of the driver’s monologue or occurs independently, and the sequence is so focused on Benigni — Bonacelli’s simultaneously strained and silent reactions serve mainly as a cruel foil to the comic performance — that we aren’t persuaded to care much one way or the other. On its own terms the monologue is certainly funny, but the filmmaker’s relative indifference to the sources of the priest’s anguish leaves a sour aftertaste that seems to go beyond Jarmusch’s intentions. (The jokey-sounding music — furnished in this sequence and the others by Tom Waits — certainly doesn’t help.)

The final sequence, set in snow-filled Helsinki (5:07 AM), is pointedly the bleakest. Here Jarmusch refers to the films of Aki and Mika Kaurismaki; three of the four lead actors — Matti Pellonpaa, Kari Vaananen, and Sakari Kuosmanen — have appeared in films by these Finnish brothers as has Jarmusch himself, and to make sure that we get the point, two of the three drunken passengers are called Mika and Aki. But the episode may well be more somber than the films of either.

Although Jarmusch gives himself sole credit for Night on Earth‘s screenplay, the individual credits for the different episodes list a total of eight translators — three French, three Italian, and two Finnish. These credits also appear in the language of the segment. It’s part of the film’s hipness that it isn’t strictly American but as multinational as its financing. Like other aspects of the film’s minimalist approach, Jarmusch’s self-positioning as a “world citizen” is both a strength and a liability: it’s a way of keeping one’s identity elusive but still cozily acceptable, apolitical but hip, easygoing but evasive, everywhere but nowhere.

The implication of such a movie and such a style is that a little formalism, some star power, and charming characters can make the whole world kin — or at least enough of it to pay back investors. And, given Jarmusch’s track record, that assumption is probably right. It’s worth noting, however, that this movie’s definition of the world takes in none of Asia or South America or the Middle East, and apart from de Bankolé, no part of the so-called third world, no Russia, no China, and apart from Mueller-Stahl, no Eastern Europe. What’s happening in the world on an everyday basis is clearly part of his subject, but what’s happening to the world is pointedly outside Jarmusch’s range and ambitions.