From the July 29, 1988 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

MONKEY SHINES: AN EXPERIMENT IN FEAR

*** (A must-see)

Directed and written by George A. Romero

With Jason Beghe, John Pankow, Kate McNeil, Joyce Van Patten, Christine Forrest, Stephen Root, Stanley Tucci, and Janine Turner.

You’ve got to get through a few layers of foam rubber before you reach what’s good (or better than good) about George Romero’s new feature. There’s a series of obstacles — cultural, corporate, ideological, stylistic, aesthetic, commercial — standing in the way of what the movie is doing at its best; they may not count for much in the long run, but it’s better to be forewarned and forearmed.

First there’s the problem of the title. I appreciate that the producers did not want to suggest that the movie is a comedy — as sticking to the title of Michael Stewart’s source novel, Monkey Shines, would have done. So a subtitle is understandable as a means of labeling the contents. But An Experiment in Fear? Whose experiment and whose fear? The phrase describes nothing in the film (except for a brief undeveloped scene with a rodent and a beady-eyed behaviorist) and nothing you can say about the film (except as an easy platitude). The film is partially concerned with scientific experimentation, but not experiments involving fear; and fear is partially what Romero generates, but not in any way involving experiments.

According to Jim Robbins in Variety, 16 other titles were tested on the public, including Ella (the name of the lead monkey character), The Primate, and Monkey See, Monkey Do. The result suggests the producers’ uncertainty about the strange bill of goods on their hands, including the question of who is experimenting with what and on whom.

Next there’s the question of the film’s prologue and epilogue, the latter imposed on Romero by the producers to replace his original ending. Prologue: Allan (Jason Beghe), the hero, wakes up beside his sexy girlfriend Linda (Janine Turner), gently strokes her bottom, and invites her to join him running; he winds up going out alone and gets hit by a diesel rig. We see his body leap into the air in slow-motion, and then see a cinder block shatter on the ground to suggest what happens to his spinal cord. As visual story telling, most of this is sparse and elegant, but David Shire’s mushy music, used behind most of it, gives it the ambience of a daytime soap.

Epilogue: A surgical incision is made in Allan’s body, and Ella, the monkey, jumps out of it, screaming. This turns out to be a nightmare — the same sort of bloody trope (in more ways than one) found in Carrie, Dressed to Kill, and a zillion other horror movies since the mid-70s, including the prologue and epilogue of Day of the Dead, Romero’s previous feature. In fact, Allan’s real operation proves to be a success; after being paralyzed from the neck down for most of the movie, he leaves the hospital on a crutch and gets into a car with his sexy new girlfriend, monkey trainer Melanie Parker (Kate McNeil). She cheerfully commands, “Come on, Ace — let’s go fishing,” to music that’s every bit as obnoxious as Shire’s bubble-bath Muzak in the prologue, evoking this time the campy finale to Beyond the Valley of the Dolls.

In between these soggy slices of bread the Monkey Shines sandwich is packed with meat — an imposing family melodrama full of faces, tension, strong feelings, and personalities, and very little wasted motion, culminating in what is probably the most protracted and successful suspense set piece in any movie this year. What the movie occasionally lacks in slickness it more than makes up in content and intensity — the maverick Romero’s two calling cards ever since his Night of the Living Dead opened 20 years ago.

Most of Monkey Shines is concerned with the mental, physical, and emotional adjustments made by Allan, a law student, when he emerges from the hospital as a quadriplegic in a wheelchair (which he controls by breathing into a small plastic pipe called a “possum”). His father long deceased, Allan is given over to the care of his devoted if overbearing mother Dorothy (Joyce Van Patten) and an ill-tempered hired nurse named Maryanne (Christine Forrest, Romero’s wife). Before long, his girlfriend, Linda, abandons him for the glib surgeon who saved his life. “If she walks out on you now, fuck her,” advises Allan’s best friend, Geoffrey, and Allan replies plaintively, “I can’t,” shortly before attempting suicide.

Geoffrey (John Pankow) is a 60s-style (i.e., counterculture) scientist working under the aforementioned beady-eyed behaviorist; he has been injecting human brain tissue into a monkey, Ella, to see if this will expand her mental capacities. Meeting with no visible success, he reports Ella as “deceased” and takes her to trainer Melanie Parker, whose specialty is teaching monkeys to assist quadriplegics. She teaches Ella to take care of Allan’s everyday needs — everything from turning the pages of his law books to feeding him and operating his tape deck.

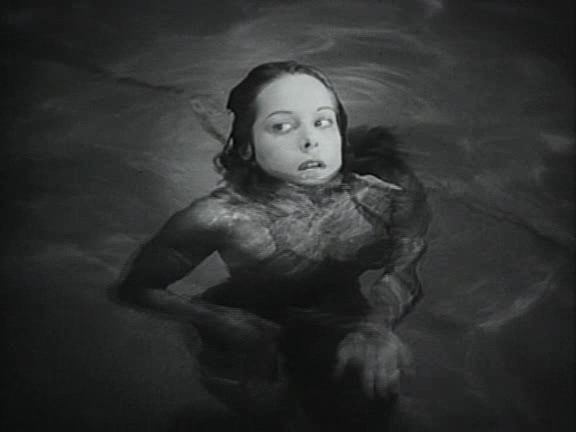

Allan quickly becomes attached to Ella as well as to her trainer, and much of the ensuing story concentrates on the implicit (and sometimes explicit) rivalries between the four females who care for him: Dorothy the mother, Maryanne the nurse, Ella the monkey, and Melanie the trainer. Melanie becomes romantically drawn to Allan, and in a highly charged erotic scene engages him in love play that enables him to suck her breasts and bring her to a sexual climax. In the meantime, Allan’s growing dependence on Ella leads to various conflicts with Dorothy and Maryanne, and the monkey’s presence disturbs his emotional equilibrium in various other ways. He has a series of vivid dreams in which he seems to share Ella’s viewpoint as she dashes through grass and underbrush (although supposedly she never leaves the house), and he admits at one point that Ella seems to tap into his own sublimated anger about his condition and draw it out.

The plot is a good deal more complicated than the above sketch suggests, but it’s better not to divulge too much more of it — except to add that Allan discovers at one point that his original paralysis was misdiagnosed — and that he may be able to move his limbs again. What matters most in the emotional dynamics that are set up are Allan’s physical helplessness and his shifting relations to the four females who take care of him, as well as to his former girlfriend, Linda.

A secondary theme also bears mentioning: Geoffrey’s antagonistic relationship to the sadistic behaviorist and vivisectionist for whom he works. This had a much greater importance in Romero’s original ending for the film, but how it was integrated with the rest of the story is unclear from the available evidence. A brief account of the original ending in the August issue of Premiere magazine describes a group of antivivisectionists staging a protest rally outside the laboratory; a scientist (apparently the behaviorist) is hit by a rock and threatens to unleash “a whole platoon of killer monkeys” that has been developed inside — apparently accidentally, as a result of Geoffrey’s experiments. It isn’t easy to square this conclusion with the wholly different one of the release version, or to guess at Romero’s original conception, but an earlier debate between Geoffrey and his boss has a lot in common with the scientific debates in Romero’s remarkable and neglected Day of the Dead, and it appears that an allusion to Romero’s Dead trilogy, with monkeys taking the place of zombies, was somehow involved.

A genuine American independent since the time Jim Jarmusch was in high school, Romero has had a tough time with the mainstream. In 1968, Columbia Pictures deemed the black-and-white Night of the Living Dead unreleasable, and American International Pictures agreed to distribute the film only if Romero would add a new, upbeat ending (which he refused to do). After Walter Reade finally picked up the film for distribution, Variety‘s reviewer wrote, “This film casts serious aspersions on the integrity of its makers, distrib Walter Reade, the film industry as a whole, and exhibs who book the pic, as well as raising doubts about the future of the regional cinema movement.” (For the past 30 years or so, Romero’s main base of operations has been Pittsburgh; even Monkey Shines was shot in the area.) More than a decade later, Romero rejected a second offer from AIP, which involved reediting his sequel, Dawn of the Dead, for an R rating. When that film opened in 1978, the New York Times reviewer Janet Maslin walked out in disgust after just a few minutes, and her action was subsequently defended by her colleague Vincent Canby, who saw the whole film and claimed that she was justified in leaving.

Meanwhile, having failed to copyright Night of the Living Dead at the time of its completion, Romero was helpless when it fell into the public domain and unable to prevent either a colorized version or two unauthorized sequels (The Return of the Living Dead parts one and two) from flooding the market — all of which helped obscure the achievement of his Dead trilogy, which stands as one of the American cinema’s key works of the past two decades, not only as horror films but as radical and provocative satires of middle America during the same period. (Arguably, it was questions of class and ideology more than gore that provoked the dismissals of Maslin and Canby, although in Romero’s case it is always difficult to separate the two.) And his continuing efforts to remain independent have ultimately failed, in more ways than one; his first studio-financed film, 1982’s Creepshow, was probably the least interesting film in his career, and reportedly he decided to make Monkey Shines for Orion only after he failed to raise the money independently.

The crucial fact about Romero’s theoretical or actual independence is that despite the continuing influence of mainstream cinema on his work, he almost never comes across as a Hollywood director — and on the few occasions when he does (as in Creepshow and the prologue and epilogue of Monkey Shines), he comes across as a bad Hollywood director. Some of his ideas may originate with Hollywood movies, but his blunt and unvarnished execution of them is something else. The issue isn’t so much the degree of his craft as the kind of craft that he employs. (From a technical standpoint, Monkey Shines was certainly no piece of cake, considering the nuances that were required of the monkey who played Ella; some shots required more than 40 takes.)

Though Romero is certainly not in their league, the “independence” of his filmmaking resembles that of John Cassavetes and Orson Welles, the latter of whom described himself in 1975 as a “neighborhood grocer” in the age of supermarkets. The techniques of all three filmmakers have an emotional and intellectual logic of their own, but not one that can be perceived through any considerations of Hollywood slickness — in fact, Hollywood slickness, and all it engenders, certainly accounts for the major problems in recognition, understanding, appreciation, and attention that their independent work has encountered. As radically different as these three writer-directors are from one another, there are striking similarities: for instance, there’s a concentrated focus of hysterical energy in the protracted climactic sequences of both Monkey Shines and Cassavetes’s A Woman Under the Influence; each shows a filmmaker completely absorbed in the volatility of his material while still remaining in masterful control of its articulation.

The Hollywood figures who seem most relevant to Monkey Shines — apart from the film’s interfering producers — are Alfred Hitchcock and the team of producer Val Lewton and director Jacques Tourneur, all three of whom could be described as masters of repression and sublimation. The use of animals to evoke (as well as provoke) sublimated instincts and repressed “female” emotions is basic to Lewton and Tourneur’s beautiful and chilling Cat People (1942), which asserts much of its power by cleverly sidestepping and discrediting the vulgar Freudian explanations offered by a psychiatrist (Tom Conway), and keeping virtually all its scenes of violence and fantasy offscreen — leading to a poetic suggestiveness that is also present in The Leopard Man, which they made the following year. (A key to the awfulness of Paul Schrader’s 1982 remake of Cat People is its inversion of those very principles — showing and spelling out most of what the original wisely left in the shadows; the vulgar psychiatrist was dropped from the plot only because Schrader as writer-director effectively took his place, showering the story with Freudian explanations to fill in all the elliptical crevices.) While Romero is more explicit than Lewton and Tourneur, he, too, leaves most of the fantasy and violence up to our imaginations, creating a similar zone of instability and uncertainty.

The Hitchcock reference most applicable to Monkey Shines is Rear Window, principally because both movies feature disabled heroes unable to flee from their tight quarters when they are eventually confronted with the rage and desperation of their own partially projected doppelgangers. The suspense in both cases is ultimately moral because, thanks to the poetic ellipses indicated above, the spectator is effectively confronted with the projections of his or her own repressed desires along with the hero’s. The fact that Allan’s “other” happens to be both animal and female only complicates the emotional texture, drawing upon his (and our) ambivalent feelings about the other females in the plot. Elements of misogyny undoubtedly play a role in all of this, but because Ella represents a fundamental part of Allan — their names even share three of the same letters — it is a misogyny that can’t be fully distinguished from self-loathing. (Mutatis mutandis, Kubrick’s Full Metal Jacket is structured around a similar male disavowal of the female, and the self-annihilation that ensues from it.)

The liberalism and commitment to minorities that characterize most of Romero’s previous work may be less immediately evident here, but they are certainly present. The plight of the disabled and Geoffrey’s 60s values are as important here as the heroic roles played by women and blacks in the Dead trilogy, and if some details of Romero’s vision have been obscured by the vicissitudes of Hollywood and test marketing, many of the essentials still shine through. Moving closer to the soul of a middle-class household than he has ever been before, he hasn’t forfeited his passion for subversion, but trained it on local truths that are perhaps even closer to home.