From the Chicago Reader (February 21, 1997). — J.R.

Can Dialectics Break Bricks?

Rating ** Worth seeing

Directed by Rene Vienet (and Doo Kwang Kee)

Written by Vienet (and Ngai Hong)

With Pai Paiu, Chan Hung Liu, Ingrid Wu, and the voices of Jacques Thebaut, Patrick Dewaere, Michelle Grellier, and Dominique Morin.

“This is a situationist film. This is not a situationist film,” begin Keith Sanborn’s notes to Rene Vienet’s Can Dialectics Break Bricks? — a French film in color being shown at Chicago Filmmakers this Saturday in a subtitled, black-and-white, letterboxed video version. I think Sanborn, an experimental filmmaker, is referring to the fact that Vienet’s film was made in 1973, the year after the Situationist International disbanded and two years after Vienet — who joined the situationists in 1963 — resigned from their ranks.

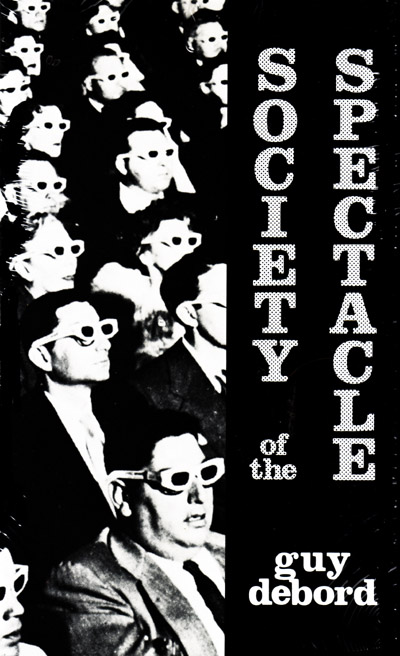

I don’t know much about the situationists, but according to critic Peter Wollen they formed out of a split within an earlier radical artistic and political group, the lettrists, who sort of took over the mantle of the French avant-garde from the surrealists after World War II under the leadership of Isidore Isou. The “dissident Revolutionary Lettrists,” as Wollen called them, were led by two young filmmakers, Guy Debord and Gil Wolman, who went on to become situationists. The only Debord film I’ve seen, The Society of the Spectacle (which was made the same year as Can Dialectics Break Bricks? and can be seen as its theoretical prequel), turned up on video at Chicago Filmmakers last October, also bearing English subtitles by Sanborn and accompanied by Sanborn’s notes. (I associate Sanborn mainly with the 1989 The Deadman, a brilliant narrative short he wrote and directed with Peggy Ahwesh, adapting a Georges Bataille story.) The Society of the Spectacle, adapted from Debord’s 1967 book of the same title, is more slapped together than composed, juxtaposing clips from all sorts of movies with large chunks of recited or printed post-Marxist theoretical text about media and spectacle. Can Dialectics Break Bricks?, which looks only slightly less slapped together, redubs (and probably recuts) a Chinese martial arts movie, The Crush, with more French post-Marxist theory, jokes, and occasional references to what it’s doing technically; roughly speaking, it’s a situationist variation on What’s Up, Tiger Lily?, Woody Allen’s 1966 redubbing of a Japanese James Bond spin-off. (I think it’s still his funniest feature, though whether it qualifies as an Allen movie is an open question. If memory serves, it used to be listed as one in the press books for Allen’s later movies, but a few years back it started being described as a movie written by Allen. The same ambiguity surrounds the credits of Can Dialectics Break Bricks?)

According to Sanborn, the French-dubbed version of Can Dialectics Break Bricks? (La dialectique peut-elle casser des briques?) was preceded by a Chinese-language version with French subtitles that no longer exists. Presumably this was a situationist version, with the Chinese dialogue mistranslated in the subtitles, though it’s possible that Vienet — who reportedly taught Chinese at the University of Paris, settled in Mainland China, taught at a university in Taiwan, and today works as a stockbroker in Hong Kong or Taiwan — supervised a Chinese redubbing of the original as well.

A key concept and technique for the situationists was detournement, which they defined as “the reemployment in a new entity of preexisting artistic elements” — that is, ripping off someone else’s work. The reappropriating and recontextualizing of a work that already exists is the aspect of Can Dialectics Break Bricks? that makes it most interesting and relevant today, aesthetically as well as politically, because it raises the thorny issue of to whom cinema, film criticism, and film history belong. Realistically, they belong to anyone with a VCR, though some would say they belong to the state — and the state today, speaking emblematically rather than literally, is Disney. It is Disney and its client states that set our cultural agendas and rewrite our official film histories and critiques via the mass media. (The claim that “the public” dictates these agendas is merely a multicorporate rationalization for a process that takes place with and without the public’s consent.)

I don’t want to restrict detournement to individual artists creating works out of previous works. The Rocky Horror Picture Show cult, which miraculously has survived for 20 years, is one of the purest examples of an audience appropriating a movie for its own purposes. Every time a movie buff copies a videotape for a friend something related is happening — a kind of cultural activity that’s outside the regulations of such institutions as studios, video-rental stores, national film archives, universities, and the print and broadcast forms of film criticism. This is something that has revolutionary implications, for the moment people start to assume responsibility for creating, disseminating, and possessing their own culture, the usual force-feeding is challenged. And the issue isn’t merely control and ownership of movies, but control and ownership of their meanings, functions, and purposes.

At the Pesaro film festival during the 60s French critic and filmmaker Luc Moullet challenged semiologist Roland Barthes by saying, “Language, monsieur, is theft.” A variation on the anarcho-Marxist adage “property is theft,” Moullet’s aphorism implies that “language” in the public realm of cinema is a matter of expensive equipment — 35-millimeter cameras and stock, sound-mixing and recording and editing machines, and so on — and therefore property. So to “have something to say” in that language you have to be rich or have wealthy patrons. And to “listen” you need to buy a film ticket or (not an option in the 60s) own a VCR — more property. In these broad Marxist terms the triumph of the proletariat becomes inextricably tied to control of production.

By writing his own agenda on someone else’s film almost a quarter of a century ago, Vienet was anticipating the kind of detournement that has been happening with increasing frequency on video, though now the means are much more readily available and relatively inexpensive. I’m thinking of critical videos or films made up chiefly of found footage that have had varying degrees of exposure without permission from the original copyright holders. The most impressive work of this kind is Jean-Luc Godard’s nearly four-hour, eight-part magnum opus Histoire(s) du cinema — a work in progress since 1988 that’s slated to premiere in its final form at Cannes this May. Other distinguished recent examples include Mark Rappaport’s Rock Hudson’s Home Movies and From the Journals of Jean Seberg, and Thom Andersen and Noel Burch’s Red Hollywood. The first two episodes in Godard’s series, each of which lasts 50 minutes, have been shown on five separate state-funded European TV channels without any permission from the copyright holders — which sets an important precedent. As Godard told me last fall, “For me there’s a difference between an extract and a quotation. If it’s an extract, you have to pay, because you’re taking advantage of something you have not done and you are more or less making business out of it. If it’s a quotation — and it’s more evident in my work that it’s a quotation — then you don’t have to pay.”

So much for the business argument, which could be applied to the other recent videos cited above — though not to Can Dialectics Break Bricks?, since appropriating almost an entire feature qualifies as neither quoting nor extracting. Yet all these works have at most a marginal relation to the film business — at least as multicorporate capitalism has redefined that realm in recent years — and consequently it could be argued that it isn’t worth the time or energy of any of the conglomerates to sue lowly independents for appropriating works that can’t be taking much business away from them. However, Red Hollywood and both Rappaport features bring value to many works that these companies regard as essentially valueless — thereby increasing rather than decreasing future video rentals. But that doesn’t mean that bureaucrats at these companies wouldn’t charge ungodly sums if they were asked for the rights — it’s a simple reflex.

To be perfectly honest, Can Dialectics Break Bricks? doesn’t exactly enthrall me, either as a martial arts movie or as a detournement of a martial arts movie. As a martial arts movie it’s fairly routine; as a situationist detournement, it doesn’t sustain itself. Sometimes it’s funny, as when the female narrator, during an extended fight sequence, gives you bibliographic references to a situationist text you should consult (“in the Gallimard edition, pages 207 and 236”). Sometimes it’s weirdly self-referential, as when the narrator notes, “Young proletarian seen through bamboo in the foreground,” or when a little boy explains a pile of corpses by saying, “They’re sick of dubbing dialogue tracks, so they’re pretending to be dead. It’s hard work, and doesn’t even pay cab fare.”

Sometimes the dialogue or narration is simply daffy: “Dialectical reason thunders in its crater.” “These bastards — suppose we burnt off the hair under their arms?” In reference to a sword: “Go put away your phallic symbol.” “You understand nothing, you dickbite Leninist. We’re gonna fuck you up. Bamboo up the ass with red ants. And we’ll burn it all up on the New Red Square.” “They can’t make butter from donkey piss.” And sometimes it’s simply dated and parochial, as in references to Themroc (a French movie of the era) and “Reich’s Function of the Orgasm in a nonmasperised version” (which I take to be a swipe at Maspero, a radical Marxist publisher and bookseller of the period) — which raises the issue of how relevant this all is to us.

In other words, both the kung fu and the post-Marxist jive become tiresome after a while. But for me, the issues of detournement and appropriation keep this video perpetually fascinating. There’s even the question of how much Sanborn’s version — as unauthorized as Vienet’s swiping of The Crush — comprises a detournement of a detournement, or how much my description of Sanborn’s version comprises a detournement of a detournement of a detournement. Sanborn claims in his notes that his version was done “not to parade a corpse embalmed among the sainted heroic dead or some cinematic or political pantheon, but in order to add to historical understanding and to release what remains of its revolutionary analysis and praxis — in short, its orgone energy.” “Orgone energy” (a kind of omnipresent sexual current) is a key term of the Freudian dissident and sexual theorist Wilhelm Reich, one of Vienet’s reference points, and Sanborn notes that Vienet made a series of detournement porn movies with titles such as The Eggplant Is Stuffed and The Cassock Has No Fly. But Sanborn reducing (or elevating) the remnants of this movie’s “revolutionary analysis and praxis” to “orgone energy” is really, I suspect, his own form of appropriation, just as my focus on the anarchistic repossession of the multicorporate cinema is mine. What if, like me, you’re not especially interested in a “historical understanding” of the situationists, but are very much concerned with contemporary cultural ownership? Or what if your interest is neither mine nor Sanborn’s but something entirely different? The point of detournement is to make the work in question your own. And since I’m the penultimate link in an extended chain of benign anticapitalist rip-offs, I can only say, be my guest.