From the Chicago Reader (June 17, 1988). — J.R.

BIG BUSINESS

* (Has redeeming facet)

Directed by Jim Abrahams

Written by Dori Pierson and Marc Rubel

With Bette Midler, Lily Tomlin, Fred Ward, Edward Herrmann, Michele Placido, Daniel Gerroll, and Barry Primus.

RED HEAT

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Walter Hill

Written by Harry Kleiner, Hill, and Troy Kennedy Martin

With Arnold Schwarzenegger, James Belushi, Peter Boyle, Ed O’Ross, Larry Fishburne, and Gina Gershon.

The silly season of summer releases is fully upon us, that time of year when expensive potboilers tend to be the only movies out there demanding our attention. Two interesting-sounding films that might have enlivened this year’s doldrums — Zelly and Me and Stars and Bars, both associated with David Puttnam’s brief stint as head of Columbia — have been unceremoniously dumped by their distributors in suburban Hillside. Paul Mayersberg’s perversely fascinating Nightfall — a head-scratching, low-budget blend of Isaac Asimov, Raul Ruiz, Jasper Johns, and psychedelic Corman movies of the 60s — departed for oblivion (or perhaps for video) before I could review it. What’s left on the table, apart from the delightful Bull Durham, are two mindless romps, each of which makes use of that veritable standby, the double plot.

Big Business, a farce whose main premise seems to be that two times Bette Midler plus Lily Tomlin equals hilarity and double your pleasure, has everything but a script and direction, which means it hardly has anything at all. Two sets of twins are born in an understaffed hospital in Jupiter Hollow, a southern backwater — one to a wealthy couple from New York, the other to local yokels — and the babies are accidentally switched. Sadie (Bette Midler) and Rose Shelton (Lily Tomlin), respectively aggressive and maladjusted, grow up to be New York executives, and their identical siblings, Sadie (Bette Midler) and Rose Ratliff (Lily Tomlin), grow up to be respectively maladjusted and aggressive down-homers.

City Sadie wants to sell Jupiter Hollow’s main business — the Hollowmade Furniture Company, left to her and her sister by their father — to an Italian businessman (Michele Placido) who wants to level it for strip-mining and condos. Rural Rose, Hollowmade’s feisty foreman, flies to New York with her sister to protest and block this move. Each pair gets booked into a suite at the Plaza Hotel, where the Italian, two troubleshooters for Sadie Shelton (Edward Herrmann and Daniel Gerroll), and eventually Rose Ratliff’s fiance (Fred Ward), a miniature-golf pro, are also staying. The ensuing confusion depends on mistaken identities, trick photography, and elevator doors opening and closing at precisely the right time, climaxing when the four women converge in a ladies’ room.

Such a schematic ground plan might have worked if the filmmakers had paid as much attention to the characters and their backgrounds as they did to the special effects. But the depiction of Jupiter Hollow is so stupidly underimagined that it isn’t even enough of a coherent caricature to constitute an insult to real country people. The movie’s vague notion of “country” suggests a community caught in some nebulous time warp, where the people hold county fairs out of L’il Abner and do-si-do to show their enthusiasm; but it’s the movie that’s caught in the time warp, suggesting that the filmmakers have never been east of Reno or south of Wall Street.

The grasp of period is equally sloppy and indifferent. Behind the credits sequence — the events leading up to the births in Jupiter Hollow — we hear Benny Goodman playing his famous rendition of “Sing, Sing, Sing,” apparently placing these events around 1938; but the version of Goodman’s number that we’re hearing is a “re-creation” done at least a couple of decades later, making the time as ersatz and as undifferentiated as the place.

This is Jim Abrahams’s first solo effort as a director and it shows him on less sure footing than his three collaborations with David and Jerry Zucker — Airplane!, Top Secret!, and Ruthless People. The elaborate network of encounters provided by the double plot and the two sets of sisters, culminating in a reductive rip-off of the multiple Groucho routine in Duck Soup, tends to overwhelm everyone involved, including Midler and Tomlin, who are reduced to their broadest and brassiest (but not their funniest) effects to distinguish between the sets of twins. Forced to limit their character traits to simplistic semaphores that can register in seconds, they are trampled underfoot by the forced mechanics; their wit is sacrificed to speed and symmetry, and everyone in the cast is dehumanized in the process. In Ruthless People, the calculation and cynicism were at least blatant givens; here they seem more like inadvertent side effects, which ultimately spur the slapstick.

In Red Heat, the double plot is systematically followed through only in the opening sequences, which show successive drug busts being carried out in Moscow by a Soviet cop (Arnold Schwarzenegger) and in Chicago by an American cop (James Belushi). But the notion of doubling is so fundamental to the project as a whole — in the contrasts/parallels between the two cops, between the two countries and cultures (reflected even in the lettering of the credits, which suggests the Russian alphabet), and between the Soviet hero (Schwarzenegger) and the Soviet drug-dealing villain (Ed O’Ross) — that Red Heat is as schematically structured around this principle as Big Business is. The key difference is Red Heat‘s somewhat more subtle ideological agenda: an attempt to counterbalance the usual right-wing elements of the police thriller and the Schwarzenegger action film with a relatively pro-Soviet bias.

Although the print ads for Red Heat pair off Schwarzenegger and Belushi in the same way that the ads for Big Business pair off Midler and Tomlin (or the ads for The Presidio and The Great Outdoors pair off their own costars), this is essentially a ruse as far as the movie’s own power balances are concerned. Schwarzenegger invariably overwhelms his costars to the same degree that he is fundamentally director-proof and auteur-proof, much as Esther Williams was in the 50s, and the script of Red Heat doesn’t hesitate to honor this principle throughout. Police detective Ivan Danko (Schwarzenegger) and police detective Art Ridzik (Belushi) are teamed up in Chicago to bring Soviet drug dealer Viktor Rostavili (O’Ross) to justice, but for all the obligatory macho competition between the two leads, there is never any threat of a real contest: Danko is essentially Zeus, and his only real adversary is Rostavili, another Russian; Ridzik is mainly around for comic relief.

Another version of the archetypal division might argue that Danko is Ninotchka, the unsmiling, exotic representative of grim Soviet determination, while Ridzik is Leon, the Melvyn Douglas character in Ninotchka (or Fred Astaire in Silk Stockings, the remake) — the witty, laid-back representative of Western pleasure and good-natured decadence. But if this is the case, it is Leon who gets seduced by Ninotchka here and not vice versa; the superiority of Danko to his sidekick as a role model is so palpable that Ridzik’s very existence seems to depend on his Soviet partner’s noblesse oblige.

While it might seem farfetched to link Greta Garbo’s Ninotchka with Arnold Schwarzenegger’s Danko, the androgynous attributes of both characters as Soviet figureheads seem to support the parallel. Danko’s first appearance, in the film’s opening scene, is in a curious coed bathhouse in Moscow populated by nude female bathers and weight-lifting males wreathed in clouds of steam; Danko shows no voyeuristic interest in this spectacle — for how can a spectacle be interested in a spectacle? (Much later, in a Chicago hotel room, Danko’s erotic disinterest is confirmed by his one-word comment on the porn that’s visible on his TV set, “Capitalism”; still later, a dialogue with Ridzik establishes that he has neither a wife nor a girlfriend.) We next see him efficiently carrying out a drug bust in a cafe, where he’s accused by a Georgian drug dealer of being compliant with the persecution of Georgians. Then, in the matching Chicago drug-bust sequence, the relevant minority group is blacks, and Ridzik’s relative laxness as a police detective is underlined by his distracted interest in some street hookers.

The press materials for Red Heat boast that “for the first time in the history of American feature filmmaking, scenes were shot in Moscow’s famed Red Square,” and that Schwarzenegger spent three months studying Russian, as well as Soviet history and culture, in order to handle the Russian dialogue in various sequences. (Ed O’Ross’s academic credentials are not discussed.) One wonders if the results of these efforts will be any less grotesque to Russians than Jupiter Hollow and Bette Midler’s hayseed accent in Big Business are to southerners.

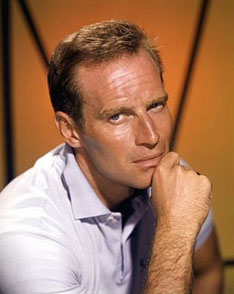

On the other hand, Schwarzenegger’s universal appeal may make this easier to get away with. Perhaps the characteristic that distinguishes Schwarzenegger most clearly from other mythic and heroic American icons such as Charlton Heston and Sylvester Stallone is his sheer otherness, a quality aided by both his usual Austrian accent and his comic-book muscles. In a sense, his role is principally that of an image rather than of a character, which is partially what made him ideally cast as a machine in The Terminator. If he also seems well cast in Red Heat, this may be because Danko is less a Soviet character than a symbolic fantasy embodiment of the Soviet Union itself, tailored for American consumption to the latest policies of detente, with Ridzik enlisted as an identification figure and surrogate spectator rather than as a symbol of the U.S.

The question that remains is whether a somewhat better than average cop movie like Red Heat winds up being “progressive” because of this styling — which is roughly equivalent to Above the Law making its villains CIA members — or just another implicitly neofascist and misogynist Schwarzenegger vehicle with slightly different trimmings. In a notorious essay published in Cahiers du Cinema in 1960, “In Defense of Violence,” Michel Mourlet penned a dithyrambic tribute to Charlton Heston that may be relevant to Schwarzenegger in certain ways, given the nature of his appeal, even if he were cast as Saint Francis of Assisi:

“Charlton Heston is an axiom. He constitutes a tragedy in himself, his presence in any film being enough to instill beauty. The pent-up violence expressed by the somber phosphorescence of his eyes, his eagle’s profile, the imperious arch of his eyebrows, the hard, bitter curve of his lips, the stupendous strength of his torso–this is what he has been given, and what not even the worst of directors can debase. It is in this sense that one can say that Charlton Heston, by his very existence and regardless of the film he is in, provides a more accurate definition of the cinema than films like Hiroshima mon amour or Citizen Kane, films whose aesthetic either ignores or repudiates Charlton Heston. Through him, mise en scene can confront the most intense of conflicts and settle them with the contempt of a god imprisoned, quivering with muted rage.”

This coincides at certain points with my earlier assertion that Schwarzenegger, like Esther Williams, is director-proof and auteur-proof, although it’s worth pointing out that The Ten Commandments and Touch of Evil both stand as ample evidence that Heston is not. In the case of Red Heat, director and cowriter Walter Hill, who initiated this project and certainly has auteurist credentials, couldn’t put much of his stamp on the proceedings, and it’s questionable whether anyone engaged to write and/or direct a future Schwarzenegger project would be able to do much better. In the final analysis, the main artistic decisions of movies like Big Business and Red Heat are basically made by bankers, not filmmakers, and the elaborate doublings of both movies count for little more than alternate ways of adding up figures: two Midlers (one urban plus, one rural minus) and two Tomlins (one rural plus, one urban minus) add up to zero; and Soviet Schwarzenegger plus American money and Belushi equals American Schwarzenegger — an axiom.