From the Chicago Reader (April 23, 1993). — J.R.

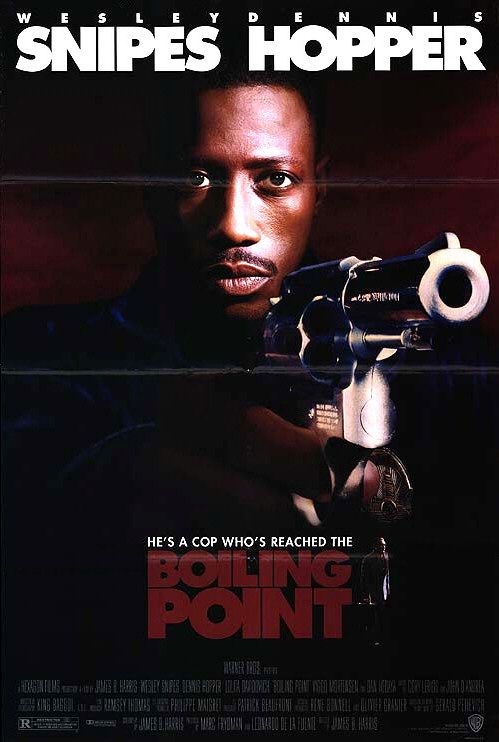

BOILING POINT

** (Worth seeing)

Directed and written by James B. Harris

With Wesley Snipes, Dennis Hopper, Lolita Davidovich, Viggo Mortensen, Seymour Cassel, Jonathan Banks, Christine Elise, and Valerie Perrine

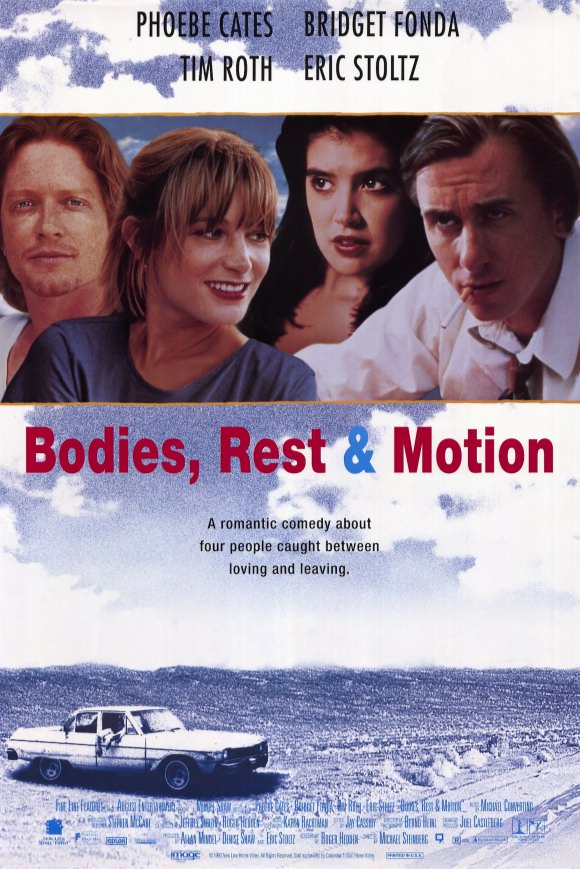

BODIES, REST & MOTION

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Michael Steinberg

Written by Roger Hedden

With Phoebe Cates, Bridget Fonda, Tim Roth, Eric Stoltz, Alicia Witt, Sandra Lafferty, and Sidney Dawson.

At least 30 or 40 years separate the sensibilities that underlie Boiling Point and Bodies, Rest & Motion, two current releases I suspect won’t be with us very long. The first, a quirky and at times oddly charming museum piece, is masquerading as a Wesley Snipes action thriller, but advertising — even wall-to-wall — isn’t everything. The writer-director, James B. Harris, who was born in 1928, produced the first three important Stanley Kubrick features — The Killing (1956), Paths of Glory (1957), and Lolita (1962) — and what’s most distinctive about this movie is its bittersweet aroma of 50s nostalgia and over-the-hill desperation, most of it wafting around a pathetically cheerful con artist called Red Diamond (Dennis Hopper) who’s simply trying to stay alive.

There’s desperation aplenty in Bodies, Rest & Motion as well, but not the sort that has the weight of lived experience — or even the relative weightlessness of recollected innocence. The calling card of this movie is its twentysomething cast, its twentysomething story and dialogue (adapted by Roger Hedden from his own play), and its spiffy postmodernist look (mainly the work of director Michael Steinberg and cinematographer Bernd Heinl).

If there’s usually something more appealing about the up-to-date than about the archaic, with these films the former proves every bit as confining as the latter. Both movies are so stuck in their blinkered generational attitudes that they seem marooned in separate solar systems, each occupying a lonely planet that seems capable of supporting only one kind of life. I can think of only one virtue they have in common, and it’s a fairly uncommon one. A cardinal sin of contemporary movies is mechanical and rhythmically monotonous crosscutting — which typically limits scenes to whatever can be shoehorned into sound bites, makes nearly all these units seem equal in importance, and renders most forms of extended continuity and development impossible. These movies have found ways to break away from this deadly pattern, though their methodologies are completely different.

Boiling Point essentially plays with and parodies the principle of symmetrically matching sound bites in order to create rhymes and continuities in its parallel plots. A federal agent working for the Treasury Department (Snipes) is granted only a week to catch a pair of ex-cons (Hopper and Viggo Mortensen) who are circulating counterfeit bills and who killed his partner; meanwhile one of the crooks (Hopper) is granted only a week in which to pay off an enormous debt to another gangster. Sometimes cutting between the two ex-cons, sometimes cutting between the parallel plots, Harris employs a number of bridges in the dialogue, so that a question asked in a first scene might be answered in a second, and often uses echoes of phrases, situations, or attitudes to match up successive scenes. Clearly interested in pointing up similarities in characters on both sides of the law, Harris is also interested in comparing and contrasting the separate age groups involved in both worlds, though apart from a hooker played by Lolita Davidovich and a junkie played by Lorraine Evanoff, it’s the older folks who arouse most of his interest and sympathy.

Bodies, Rest & Motion exploits difference more than sameness in its crosscutting, mainly alternating lively dialogue between characters in nondescript interiors with one of these characters driving around alone in visually striking settings. The picture also breaks with the sound-bite principle by allowing most of its scenes to develop in more sustained stretches, as a play does, giving us more opportunity to become acquainted with the characters and giving the characters more time to become acquainted with one another.

The only problem is that when all’s said and done there isn’t very much to know about these people. The same holds true for most of the people in Boiling Point. A lack of imagination on the part of the filmmakers in both cases seems to fit snugly with a desire to keep these movies light on their feet; yet paradoxically the undertow of dissatisfaction and failure that seems to characterize all the lives we’re observing is just about the only thing that keeps the plot of either movie in motion. Bored with themselves and each other, these people are vaguely hoping to find a way out of their stagnation, but not at all sure how to do it. What mainly keeps them interesting and alive is their style, not their content — the case with both movies as well.

Just like its Generation X characters — not to mention its better-than-average dialogue and its handsome desert landscapes — Bodies, Rest & Motion seems all dressed up with no place to go. Still essentially a theatrical work in much of its talk and staging, it has been directed with a nice feeling for transitions and intervals, but the randomness of its characters’ decisions keep the movie from carrying the impact it wants to have, even as a generational “statement.”

The setting is the fictional mall-filled town of Enfield, Arizona — “pop. 91,246,” as if that tells us anything about it. A dissatisfied TV salesman named Nick (Tim Roth), recently fired for unstated reasons, is about to move to Butte, Montana, also for unstated reasons. He lives with Beth (Bridget Fonda), a waitress who plans to move with him, but the woman we initially see him with — his former girlfriend, and his and Beth’s best friend — is Carol (Phoebe Cates), who lives next door to them and manages a boutique.

The fourth main character is Sid (Eric Stoltz), a housepainter who — unlike Nick, Beth, and Carol — has lived all his life in Enfield and doesn’t mind this at all. (“My father says that if you stay in one place long enough, your luck knows where to find you.”) He arrives at the couple’s house on Friday, Nick’s last day at work, to add a coat of paint to the walls before new tenants move in on Sunday. Nick has lunch at the mall with Carol, who provides him with a map for the move to Butte, suggesting stopovers en route in Las Vegas and at his parents’. Nick, long out of touch with his parents, says he doesn’t want to visit them — “I wouldn’t know them” — but after leaving work he sets off on an unannounced drive to their house. Meanwhile Sid smokes grass first with Carol then with Beth. He winds up going to bed with Beth and subsequently announces that he’s in love with her . . .

Some of what ensues reminds me in spots of Wim Wenders’s Paris, Texas, with the same sort of postmodernist mixture of self-pity and irony about vanished roots, cultural and familial. At its most obtrusive the notion of cultural alienation takes the form of loud Indian chants heard periodically on the sound track, of Nick asking a Navaho filling-station attendant “what the wind means” and getting the answer he deserves (“It’s just the wind, and I’m just a Navaho”), and of Nick buying a cheap imitation Indian headband to wear on his way back to Enfield. Even more heavy-handed — and theatrical in a bad sense — is the handling of lost family roots, more self-pitying than ironic, after Nick reaches his destination.

The coy, awkward title is derived from Isaac Newton’s first law of motion, the first thing to appear on-screen after the credits: “A body at rest or in motion will remain in that state unless acted upon by an outside force.” In obvious terms, this applies to all four leading characters; in less obvious terms, it refers to the audience watching them and what is or isn’t happening to its collective thoughts and feelings.

The perky yet affectless results are a kind of Antonioni Light for the 90s, featuring alienation and aimlessness without an underlying sense of horror or terror — just a few shrugs, a few homilies about absence of direction, and a lot of photogenic lassitude.

In terms of story and action, the gratuitously named Boiling Point has even less going for it. One’s indifference to what happens in terms of the plot is virtually sealed by the final titles, which explain the ultimate fate of the characters and seem totally beside the point. But in terms of obsessional feeling, this movie has more intensity, more emotional aftertaste.

As a writer-director-producer, James B. Harris is considerably more eccentric than he was as a producer for Kubrick — apart from his relatively impersonal The Bedford Incident (1965), on which he took no writing credit, an efficient, noncomic cold-war thriller that might be said to represent his version of Dr. Strangelove. Some Call It Loving (1973) — his weirdest and least commercially successful feature, though my personal favorite — is a solipsistic fairy tale about a somnambulistic jazz musician who purchases a genuine sleeping beauty at a carnival and finds himself unable to cope with her once she wakes up.

Harris’s next two features, Fast-Walking (1982) and Cop (1987), established his reputation as a macho-thriller specialist adapting noir-ish novels, and there are significant crossover elements between them and Boiling Point, adapted from Gerald Petievich’s Money Men (the first two films star James Woods, the first and third relate to male prisons, the heroes of the second and third have painfully unsuccessful marriages involving children). With the exception of The Bedford Incident, which takes place exclusively on a submarine and includes no women, all of Harris’s features are both misogynist and kinky in certain respects, though it should be noted that they’re relatively self-conscious — thoughtful and troubled — about these biases, and even rather haunted by them. (Somewhere at the root of the films’ misogyny is a madonna-and-whore view of women that remains preoccupied with sexual innocence and male impotence.)

Interestingly enough, the Harris film with the closest thematic links to Boiling Point is Some Call It Loving. Both are centered on doomed, dream-driven, sexually obsessed, and lonely men whose dreaming is intimately tied to jazz and a nostalgia for popular music of the 50s. In Some Call It Loving the key pop records are “Mr. Touchdown” and Nat “King” Cole’s version of “The Very Thought of You”; in Boiling Point it’s Johnny Mercer’s “Dream,” performed in the Palace ballroom on Hollywood Boulevard by the Danny May Orchestra and featuring a vocal quartet whose harmonies suggest the Four Freshmen.

For Red Diamond, dancing at the Palace to big-band swing functions not only as a substitute for sex, but as the only dream for himself he can keep alive in his head. (The only other dreams he has — mainly get-rich-quick schemes — appear to exist for the scamming of others and are seemingly pursued out of dire necessity.) The only women in his life are Mona (Valerie Perrine), a coffee-shop waitress who hasn’t entirely forgiven him for getting her to turn tricks to pay off his debts, and Vikki (Davidovich), a high-priced hooker he usually prefers to take dancing when he hires her services. Working with a remorseless, giggly killer named Ronnie (Mortensen) who’s roughly half his age, Red offers the game plans, the real or imaginary pretexts, and the dreams for their criminal operations, while Ronnie basically performs the murders — a relationship that seems to sum up Harris’s view of the generation gap.

Jimmy (Snipes), the federal agent who’s after Red and Ronnie because they killed his partner, is bitterly estranged from his wife but still drawn to her and much preoccupied with their little boy. But he’s also sexually involved with Vikki, though as a sometime lover rather than as a client. He’s supposed to be the hero of this movie, but Harris seems so little involved with Jimmy’s revenge motive — a generic staple at least since The Maltese Falcon — that Snipes, a very talented actor, seems a little lost without a full character to play.

Harris seems equally incurious about Ronnie, whom he seems to regard as an airhead and zombie. Indeed, the only people who seem to engage his full interest are the older characters — the earthy Mona and a number of Red’s criminal contemporaries who are either lower or higher than him on the economic ladder (most notably Seymour Cassel and Jonathan Banks). Most of these men are fairly callous individuals, but because they all seem equally doomed we wind up caring about them. At their best this rogues’ gallery of bit players, along with Hopper, recalls the older men in Kubrick’s The Killing — Joe Sawyer, Jay C. Flippen, Kola Kwarian, whose gritty solitude and stoical martyrdom linger in the mind long after the thriller plot is absorbed and forgotten.