From Slate (posted June 23, 2009). — J.R.

One of the key paradoxes of contemporary movie culture is that some film lovers claim that cinema is dying, others maintain that it’s entering a renaissance, and both factions are right. It all depends on whose movie culture you’re talking about.

The problem is how elastic and imprecise our terminology has become. Nowadays, when somebody says, “I’ve just seen a movie,” we don’t necessarily know whether the speaker saw it in a theater or on a mobile phone, alone or with a thousand other people, on celluloid or on a disc. These aren’t really the same experiences, even if we choose to call them all The Godfather or Up. And when it comes to distinguishing between film history and advertising, we may be even more confused.

One reason why we may be entering a renaissance in film viewing is that we no longer have to go to Paris or New York in order to learn anything comprehensive about the history of the medium as an art form. We can, in fact, live almost anywhere, at least if we own a multiregional DVD player — and nowadays one can acquire one of these for less than $50. Of course, those who argue that cinema is dying could also note that most viewers have been happy to stay in their designated regions and narrower range of consumer choices and to remain blissfully unaware of DVD regional codes, much less simple ways of circumventing them.

If we do want to bone up on film history, some of our finest scholars are busy turning out DVD extras, and a few of them are even better at this kind of work than they are in their writing, which offers fewer opportunities of illustrating their points. Compare, for instance, the audiovisual essays of Joan Neuberger and Yuri Tsivian on the Criterion Collection DVD of Sergei Eisenstein’s Ivan the Terrible with these writers’ recent monographs on the same subject. Or compare Tag Gallagher’s analysis of Max Ophüls’ Earrings of Madame de… for the same label with his online article about Ophüls for the Australian Web site Senses of Cinema, which focuses on the same scene from the same film. Yet once we start moving closer to mainstream film culture, the improvement in our understanding becomes a little less evident.

What do we mean when we use the term “film noir”? It works fine in video stores, yet unlike other genre labels, it removes us from the experiences that contemporary audiences had when they saw the same films. The term derives from a series of thriller novels published in France by Gallimard, “Série noire,”and superimposing a French identity over American products like Double Indemnity (1944), The Big Sleep (1946), Kiss Me Deadly (1955), and even Chinatown (1974) makes us feel Continental and stylish and therefore less responsive to the films’ social meanings than the original American audiences were. We now use the term as a kind of historical shorthand, but often without realizing that the abbreviated history in question is also being subtly rewritten and mainly for the convenience of the DVD labels — part of whose business is to shape the choices of shoppers.

Regarding terms like director’s cut and restoration: The fact that these categories are now integral parts of sales pitches seriously diminishes the possibility of their serving as accurate descriptions. Arguably, one reason why the film industry has encouraged and promoted the concept of director’s cuts, even though this might appear to be counter to its own interests, is that it enables a film’s owner to sell the same product to the same customer twice — or even, in a few special cases, three or four times. Presumably, if you recut somebody’s film, the damage isn’t serious because it can always be “restored” on DVD. The basic mythology appears to be that every film has two versions, a correct one and an incorrect one. But in fact this isn’t quite true. A better paraphrase of the mythology would be, more paradoxically, that every film has at least two versions — a correct one and a more correct one, to be succeeded in turn by further upgrades.

One good example is the 2004 version of Samuel Fuller’s The Big Red One, available on DVD, produced by Richard Schickel, and subtitled The Reconstruction. To my mind, neither the 1980 release nor Schickel’s alleged duplication or approximation of the original longer edit of the film qualifies as a director’s cut. For one thing, Fuller was adamant about not wanting any offscreen narration, and offscreen narration figures in both of the existing versions. If I had to choose between these two versions, I’d choose the more recent one, although this is hardly the same thing as calling it the “survival” of Fuller’s 1980 cut as the blurb on the box does. But in the kind of journalistic shorthand that we’ve become accustomed to, it automatically takes on the status of a director’s cut.

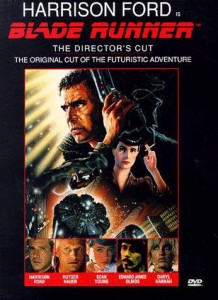

To take an extreme example, what about the eight separate versions of Blade Runner, at least half of which have been widely shown? These have included, apart from the initial 1982 release, cuts known respectively as the “original director’s version” (though, ironically, disowned by its director, Ridley Scott) in 1990; three subsequent versions, all purporting to be “director’s cuts,” growing out of Scott’s objections to the 1990 release; and, finally, the one that was actually approved and released in 1992. Yet even these five versions — all described in copious detail, along with two more, in Paul M. Sammon’s once-exhaustive 1996 book, Future Noir: The Making of Blade Runner — have finally been succeeded by a more carefully wrought 25th anniversary edition, hopefully definitive, known simply as Blade Runner: The Final Cut, prepared by Scott and released in 2007.

The havoc played with ordinary language and its meanings by this slapstick history is duplicated, in smaller but no less telling ways, in the mainstream labels often attached to various works by Orson Welles, particularly by writers who want to simplify the issues involved. Welles was an industry outsider whose work methods confounded most of the usual categories, so his work has been wrongly described much more often than that of most other filmmakers, and I’ve encountered these obfuscations often as a Welles scholar. The bottom line is that Welles never had a final cut on either Touch of Evil or Mr. Arkadin, so claiming to “restore” something that never existed, as a good many publicists and commentators do, is tantamount to fibbing. And the same thing applies to deleting and then redoing part of Welles’ original soundtrack for Othello (a film on which he did have a final cut), which is also, usually, called a “restoration” by marketers and reviewers alike.

When I worked as a consultant on a 1998 re-editing of Touch of Evil based on a set of suggestions Welles made to Universal in 1957 about improving its own version, our team took pains to clarify that our version wasn’t — and couldn’t be — anything else but an attempt to follow those suggestions. But our fine distinctions got lost in the shuffle, because Universal and others had already been describing a longer version, belatedly discovered in their vaults in the 1970s, as both a restoration and a director’s cut, and these erroneous labels often got affixed to the 1998 rerelease as well. Even on the jacket of the 50th-anniversary box set, released last year and containing all three versions, which I worked on in several capacities, our recut is erroneously described as both “restored” and “definitive.” In my own preface to the Welles memo inside that package, I was obliged by Universal to use the word “restored,” so I had to settle for placing that word inside quotation marks.

Description constrained by marketing is nothing new to me. Many years ago, when Voyager got me to write liner notes for Confidential Report, one of the multiple versions of Mr. Arkadin, on laserdisc, they wouldn’t allow me to call it the second-best version (in terms of its conformity to Welles’ editing). Years later, when I worked on Criterion’s ambitious 2006 box set devoted to many of these multiple versions, it finally became permissible to express this preference. Yet the fact that this box set is called The Complete Mr. Arkadin epitomizes the degree to which distortions become inevitable. “For my style, for my vision of film,” Welles once declared to André Bazin, “editing is not an aspect, it is the aspect.” By this criterion, no edition of any film that Welles never completed could meaningfully be called complete. But if your criterion is that of a collector and a footage fetishist, the rules change. And it’s the collectors and those servicing them that are rewriting much of our film history.

This phenomenon is by no means exclusively American. The mania for expansion now seems universal, much as the taste for succinctness in films flourished when double bills were more common. The new philosophy appears to be that more is always better. One of the best and most serious English DVD labels, Masters of Cinema, boasts on the jacket of its latest release, Michelangelo Antonioni’s Il Grido, “Previously unseen footage deleted from the director’s cut.”