From the December 7, 2001 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

Band of Outsiders

Rating **** Masterpiece

Directed and written by Jean-Luc Godard

With Anna Karina, Claude Brasseur, Sami Frey, Daniele Girard, Louisa Colpeyn, and Ernest Menzer.

To gauge the historical significance of Jean-Luc Godard’s Band of Outsiders (1964) — getting a week’s run in a lovely new print at the Music Box — it helps to know that it was made four years after François Truffaut’s Shoot the Piano Player and three years before Arthur Penn’s Bonnie and Clyde. Both Band of Outsiders and Shoot the Piano Player are low-budget black-and-white French thrillers adapted from American crime novels translated into French for the celebrated Serie Noire collection, and they were abject box-office flops on both sides of the Atlantic — though today they embody the glories of the French New Wave in a good many people’s minds. By contrast, Bonnie and Clyde, a Hollywood movie in color that was profoundly influenced by these two films, was a huge success, and its lyrical depictions of violence changed the direction of American cinema.

All three films are mixtures of tragedy and farce, violence and romance, with an uncertain emotional tone. When Band of Outsiders and Shoot the Piano Player were first released, audiences didn’t know what to make of this mix, but when they saw Bonnie and Clyde they were exhilarated by its ambiguities. In part, this may have been because Bonnie and Clyde‘s color, stars, and period trappings were more glamorous, the violence much gaudier, and the storytelling more straightforward. Whatever the reason, audiences were by and large more ready for it in 1967 than most critics were. One might even say that while the New Wave films refused to gel for ordinary viewers, the eccentric, cavorting bank robbers of Bonnie and Clyde evoked such a bittersweet response that a kind of movie postmodernism was born — a cynical reluctance to take straight either comedy or tragedy in most crime pictures that has persisted ever since.

Most of the critics of Bonnie and Clyde eventually recanted; one who liked the movie from the beginning and scolded her colleagues for missing the point was Pauline Kael, making her exciting debut in the New Yorker with a long, multifaceted article about the movie and, as an avowed fan of Shoot the Piano Player and Band of Outsiders, noting how much screenwriters Robert Benton and David Newman had learned from Godard and Truffaut. (In fact, Benton and Newman had originally offered their script to both directors.) Though Truffaut quickly surpassed Godard as the public’s sentimental favorite among the new and volatile French directors, Band of Outsiders made a more profound impression on American independent filmmakers in the 80s and 90s. The melancholy trio of Jim Jarmusch’s Stranger Than Paradise (1984), planted in downscale urban and suburban settings — two dandyish, deadbeat best friends and the shy, younger woman they’re smitten with — would have been inconceivable without Godard’s adorable threesome. And when this brand of hipness met the postmodernist sense of reference and context of Hal Hartley and Quentin Tarantino, Godard’s movie was converted into something resembling a house style and a self-conscious coat of arms: both Hartley and Tarantino were visibly infatuated with a desultory dance called the Madison, performed in mutual — and paradoxically synchronous — solipsism by Godard’s three leads in a café, and Tarantino even called his production company A Band Apart, after the original French title, Bande à part.

Shot in 25 days for $120,000 in early 1964, Godard’s seventh feature offered a striking contrast to his previous film, the high-priced and star-studded Contempt. It’s as if he’d deliberately followed his heaviest and most portentous production with one of his lightest — a virtual throwaway that opens, behind the credits, with jaunty piano music accompanying rapidly alternating close-ups of the three leads. Manny Farber’s celebration of what he called termite art — the kind of art more preoccupied with its own activity than with making an impression, unlike the grandiosity of elephant art — culminates in his citing “the inclement charm Godard gets with drizzly weather, the Paris outskirts, and three nuts scurrying around the same overcast Band of Outsiders terrain,” the precise opposite of the elephantine scale and gloomy splendor of Contempt.

But a closer look at Band of Outsiders belies or at least complicates such an impression. Indeed, I’ve often suspected that the film’s popularity among American mainstream critics has something to do with the relative absence of politics and social concerns — interests that have characterized Godard’s work ever since. His next feature, A Married Woman, clearly displayed these sociological concerns; when his latest, In Praise of Love, recently concluded the New York film festival, some local critics predictably held forth on how unwelcome, tiresome, and unfashionable Godard’s anti-American swipes had become in the wake of September 11 — as if their own solipsism were more interesting to everyone else on the planet.

Band of Outsiders has its sociological elements, but you have to dig for them, and its anti-Americanism is mixed with too much affection for American culture to be taken straight. What seems most striking today, in spite of the many moments of comedy and elation, is how painfully candid and personal it is in its despair and disillusionment. That Godard himself narrates the film enhances the sense of intimacy one feels he has with each of his three main characters. Arthur (Claude Brasseur) and Franz (Sami Frey) are named after two of his favorite authors, Rimbaud and Kafka, both of whom led bleak lives, and Rimbaud’s macho brutality and Kafka’s shyness seem to represent opposite sides of Godard’s personality; this makes it all the more appropriate that Odile (Anna Karina) — the young suburban woman Franz has met and befriended in an English class in Paris, whom both men are infatuated with in their separate ways — prefers one yet ultimately winds up with the other. (Rimbaud gave up poetry at 19, then wandered through Europe and Africa and may well have become a slave trader, while Kafka was a frail neurotic who worked in an insurance office and felt terrorized by his father; the affinities extend to Brasseur and Frey’s physical appearances.) Even more pointedly, Odile’s full name is Odile Monod, the maiden name of Godard’s mother. In 1964, Godard said the film was partially inspired by French novels of Georges Simenon and Raymond Queneau “with a prewar atmosphere” and was an attempt “to re-create the populist, poetic climate of the prewar period” — a climate he may well have associated with his mother, though in the same interview he claimed the name Odile came from a novel by Queneau about the Surrealists.

Even more relevant is that Godard was not only married to Karina when he made Band of Outsiders but was in love with her — and as a consequence he could design entire sequences simply to watch her walk or run. I can’t say that the misogyny of most of Godard’s other films is entirely absent here; when Arthur starts taking out his frustrations by slapping Odile, one’s feelings go out to her more than him, but his roughness still reeks of the machismo of prewar icons such as Jean Gabin. However, in this film, unlike A Woman Is a Woman and Alphaville, the machocentric rhetoric seems mediated by a genuine sympathy and respect for Odile that, for all her exaggerated girlishness, is not simply patronizing. On some level, Godard seems to identify with her as well as with the guys — just as in Breathless, as film critic James Naremore recently pointed out to me, he’s put some of himself in Jean Seberg (such as his taste for Faulkner) as well as in Jean-Paul Belmondo.

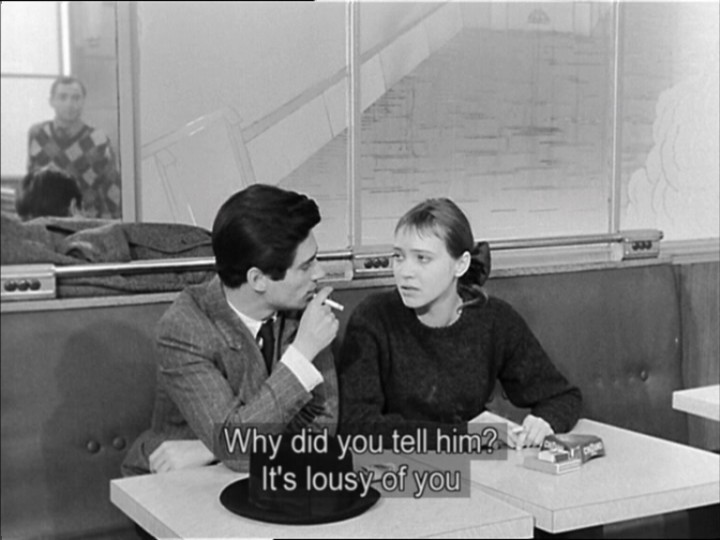

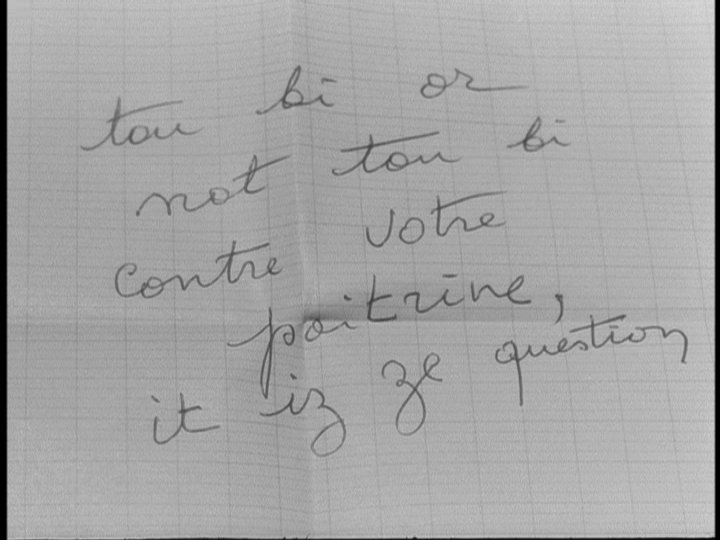

This is undoubtedly why in Band of Outsiders‘ beautiful, hilarious, and completely implausible English class — where the teacher (wonderfully performed by Daniele Girard) assigns the students to translate back into English a French translation of a scene from Romeo and Juliet, while Arthur keeps slipping Odile love notes (“Tou bi or not tou bi contre votre poitrine [against your chest], it iz ze question” and, more gruff and Gabin-like, “You look old-fashioned with your hair like that“) — Odile is one of the few students one can actually imagine taking the course. Behind her, for instance, is a balding middle-aged man with glasses who sneaks slugs of whiskey from a small bottle inside a fake book.

The plot is an almost standard-issue failed caper: two weeks before the action begins, Odile idly tells Arthur about a stash of money hidden by a lodger at the suburban villa where she lives with her aunt and guardian Madame Victoria (Louisa Colpeyn), and they plan a robbery with her reluctant cooperation. The comic discrepancies between what they plan, fueled by B movies, and what ultimately happens were also standard issue by 1964; Big Deal on Madonna Street had been made six years earlier. But the modernist inflections on this theme were something else again. Early in the picture Franz and Arthur pantomime Pat Garrett gunning down Billy the Kid with a single shot, and Arthur rolls around on the pavement in a protracted cadenza of mock agony that goes on for so long it starts to look real. Toward the end of the picture, when Arthur really gets gunned down by a cousin who’s greedy for the loot, he gets shot no less than five times before he finally shoots back and then falls, spinning to the ground in a corkscrew motion; his actions look so unreal they seem absurd. This is clearly part of what alienated audiences when the film was first released, a time when movie conventions still made some nominal distinctions between unreal (comic) and real (serious). I recall being piqued and intrigued and emotionally confused when I first saw the movie in 1966, when it was getting a second run at one of the grind houses on Manhattan’s 42nd Street — the first home of many of the B films Godard was emulating. If the fake death had been funnier and the real death more serious, the movie’s first run at the art house might well have lasted more than a week.

Five minutes into the picture Godard’s narration self-consciously fills in the plot specifics for latecomers: “Three weeks earlier, a pile of money, an English class, a house by the river, a romantic girl.” It was actually two weeks earlier, according to his previous narration, that Odile told Arthur about the money, but at least the allusion to an obscure Fritz Lang thriller, House by the River, is precise; and as with a later continuity error, when Arthur and Odile climb down the metro steps at Place Clichy to board a train at Boulevard Saint Michel, it’s always the line of the poetry that matters in Godard, not the line of the narrative. Later Godard also informs us that Arthur delays the robbery until nightfall “in keeping with the tradition of bad B films” — giving the three characters enough time to run through the Louvre in nine minutes and 45 seconds, breaking the record “previously set by Jimmy Johnson of San Francisco” by two seconds. And when a character calls at one point for a moment of silence in a cafe — “a true minute of silence that lasts an eternity” — the sound track obediently (or maybe not so obediently) shuts off for a little over half that time, creating an uneasy truce between illusion and reality that’s characteristic of the film as a whole. A similar preoccupation leads to sequences of crosscutting between segments with and without music, including the trio’s famous Madison strut. Equally telling is the “Jimmy Johnson” brand of art appreciation, which Godard mocks as well as imitates in his own methods of cultural citation — a succinct illustration of his ambivalence about America that recalls the account Truffaut once gave of Godard, in typical fashion, plowing through 40 books at a friend’s house over the course of an evening by reading just the first and last pages.

These are all features of the movie’s jokey surface, which is what most reviewers prefer to remember. Less remembered but no less present is a painful sense of suburban drabness and boredom, unemployment, frustration, and disillusionment — all reflected in Raoul Coutard’s superb capturing of overcast weather and polluted river vistas in varying shades of gray, as well as in the sad and wistful waltzes of Michel Legrand’s score, performed by brass instruments mainly in their lower registers (which we hear more often than the jazzier up-tempo patches). It seems that most middle-aged reviewers credit the gags for the film’s youthful feel — leading some of them to wax nostalgic about their own carefree days, forgetting that the film’s sense of dead-end hopelessness is no less a part of the experience of being young.

Some biographical information about Godard’s early years seems useful here. The sense of failure dogging the lives of Rimbaud, Kafka, and the young Faulkner is matched by the sense of drift in the troubled life of Godard before the release of his first feature in 1960, shortly before he turned 30. The son of a doctor and a banker’s daughter who grew up in Switzerland and Paris, he became interested in movies in his late teens, around the same time his parents divorced; he was then living with aunts and uncles on his mother’s side in Paris and periodically stealing small amounts of money from them. The next year he accompanied his father to Jamaica when the doctor decided to emigrate there, then stayed behind after his father changed his mind and returned to Switzerland; for a year and a half Godard traveled around South America — the final destination of the runaway couple at the end of Band of Outsiders — until his father refused to support him any longer. (This information comes mainly from a 1992 essay by Colin Myles MacCabe, who may have lost his status as Godard’s official biographer because the essay included the following sentence: “A few nights on the beach of Copacabana and a pathetic failure to raise money as a homosexual prostitute were the prelude to a return to Switzerland and Paris, where Godard contributed to the first issues of Cahiers du Cinéma.”)

His petty thefts apparently continued after he returned to live with his relatives in Paris, though his mother found him a job in Swiss television, which was just getting started. Then a more serious theft from nonrelatives landed him in a Zurich jail, and his father, after bailing him out, put him in a psychiatric hospital for an extended period. His mother came to his rescue again shortly before she died in a traffic accident in 1954, finding him a job on a construction crew building a Swiss dam. That dam became the subject of his first film, a short documentary that he financed himself and that effectively launched his career.

I realize that it’s vulgar and facile to associate too closely Godard’s personal background and the emotions in Band of Outsiders. Yet it seems worth doing to some degree in this case to underline the conviction behind some of the film’s more melancholy aspects — such as its acute sense of failure and loneliness, evident even in the klutzier moments of the dance sequence — which are inextricably tied to its lyricism.

Perhaps the apotheosis of this occurs in the romantic tryst shared by Arthur and Odile — narrated, for once, not by Godard but by Odile, half reciting and half singing a song with words by poet Louis Aragon that begins while they’re riding on the metro and then continues on the sound track, hovering over solitary, anonymous figures on the train and scattered across the Paris nightscape, before concluding with the couple in Arthur’s bed while her voice remains offscreen. The sequence is bookended by brief scenes in which each character tells the other his or her family name, as if to mark the fusion of the personal with the universal; Arthur’s last name, we discover, is Rimbaud. Australian critic Adrian Martin has rightly connected this sequence to the more celebrated evocations of the musical in Godard’s other films — most notably those in A Woman Is a Woman and Pierrot le fou, which also feature Karina — and even to Godard’s review in Cahiers du Cinéma of The Pajama Game. What makes the sequence so potent for me is the way it intertwines affection and solitude — a juxtaposition of lovemaking with a profound sense of isolation, as if neither could truly exist without the other.