From the August 23, 1991 Chicago Reader. This review is also reprinted in my first collection, Placing Movies (1995). — J.R.

BARTON FINK

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Joel Coen

Written by Ethan Coen and Joel Coen

With John Turturro, John Goodman, Judy Davis, Michael Lerner, John Mahoney, Tony Shalhoub, and Jon Polito.

I’m not one of the Coen brothers’ biggest fans. I walked out of Blood Simple, their first feature. The main sentiment I took away from Raising Arizona and Miller’s Crossing — their second and third efforts, both of which I stayed to the end of — was that at least each new Coen brothers movie was a discernible improvement over the last. Raising Arizona may have had some of the same crass, gratuitous condescension toward its country characters as Blood Simple, but it also had a sweeter edge and more visual flair. In both craft and stylishness, Miller’s Crossing was another step forward, and even if I never really believed in either the period ambience or the characters — the dialogue bristled with anachronisms, and Albert Finney’s crime boss seemed much too blinkered and naive for someone who was supposed to be ruling a city — the film nevertheless demanded a certain attention.

On its own terms, Miller’s Crossing was the work of a pair of movie brats (both in their mid-30s) eager to show their emulation of Dashiell Hammett but, in spiky postmodernist fashion, almost totally indifferent to Hammett’s own period — except for what they could skim from superficial readings of Red Harvest, The Glass Key, and a few secondary sources. Historical and psychological veracity consisted basically of whatever they could get away with, based on the cynical assumption that their audience was every bit as devoid of interest in these matters as they were. Unlike their earlier efforts, Miller’s Crossing was a commercial flop — an undeserved one, given its visual distinction and its strong performances. Even if the film was soulless, it showed an obsession with its Hammett-derived male-bonding theme that suggested the Coens were aspiring to something more than crass entertainment; for better or worse, it looked like art movies were their ultimate aim.

Barton Fink confirms this impression with a vengeance. Unfortunately, the movie ultimately founders on the Coen’s primary impulses, which drive them to use a festival of fancy effects; whatever their ambitions, midnight movies are still the brothers’ metier. The movie’s arty surface fairly screams with significance, but the stylistic devices are designed for immediate consumption rather than being part of a coherent strategy. As entertainment, Barton Fink is in some ways even better than Miller’s Crossing, though also just as adolescent and much less engaging when seen a second time. Last May it received the unprecedented honor of being awarded three top prizes at the Cannes film festival — for best picture, best director, and best actor (John Turturro) — which will undoubtedly help it commercially in Europe. Whether these awards will count for much in the more hidebound U.S. still remains to be seen.

The president of the Cannes jury was Roman Polanski, who took the job only after demanding that he be allowed to handpick his own jury members. Considering the indebtedness of Barton Fink to Polanski pictures like Repulsion, Rosemary’s Baby, and The Tenant — in its black humor, treatment of confinement and loneliness, perverse evocations of everyday “normality,” creepy moods and hallucinatory disorientation, phantasmagoric handling of gore and other kinds of horror as shock effects, and even its careful use of ambiguous offscreen sounds — the group of awards should probably be viewed more as an act of self-congratulation than as an objective aesthetic judgment.

Nevertheless, Barton Fink is an unusually audacious movie for a major studio to release — not only because of its bizarre form and content, but also because the Coens had complete creative control. Whatever else they might mean, then, the Cannes prizes cannot be regarded as automatic nods to the commercial tried-and-true. In terms of overall meaning, Barton Fink qualifies as a genuine puzzler. Considering how transparent most commercial movies are, Barton Fink at least deserves credit for stimulating a healthy amount of discussion.

The title hero is a working-class Jewish playwright (Turturro) who has just scored a hit in New York with his first play, Bare Ruined Choirs; the year is 1941. Offered a lucrative Hollywood contract by Capitol Pictures that he reluctantly accepts — he doesn’t want to compromise his passionate vision of a theater “by and for the common man” — he goes to the west coast, checks into a faded deco hotel called the Earle, and goes to see Capitol’s hysterically effusive studio head Jack Lipnick (Michael Lerner), who promptly asks him to write a wrestling picture for Wallace Beery.

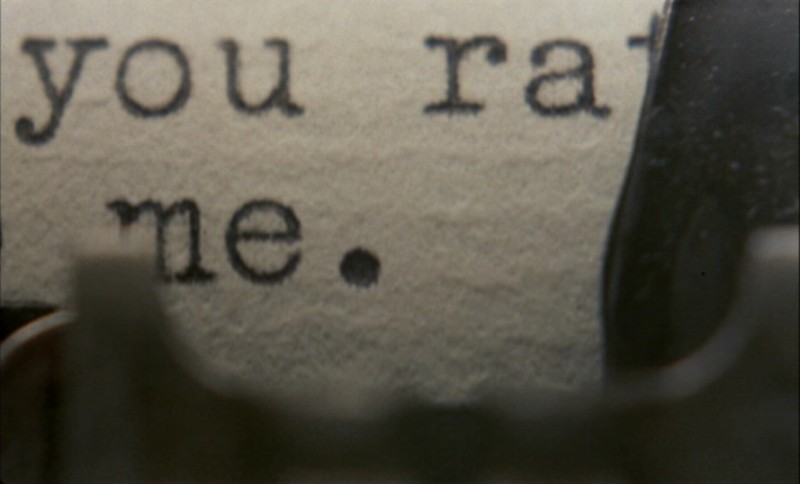

Alone in his squalid room at the Earle, Barton finds himself painfully blocked, unable to get beyond a few scene-setting sentences. The sound of sobbing (or is it laughing?) in the next room prompts him to phone the front desk, and a few minutes later his next-door neighbor (John Goodman) — a burly, friendly fellow who identifies himself as an insurance salesman named Charlie Meadows — pays him an apologetic visit. Barton recognizes him as exactly the kind of working stiff he’s interested in writing about, and they soon become friends — though Barton is too full of himself to show much interest in learning anything about Charlie (who repeatedly announces that he has stories to tell).

Barton meets with Ben Geisler (Tony Shalhoub), the flinty producer assigned by Lipnick to the wrestling-picture project. He also meets W.P. Mayhew (John Mahoney), an alcoholic southern novelist turned screenwriter clearly modeled after William Faulkner, and Audrey (Judy Davis), Mayhew’s abused secretary and mistress, whom he clearly takes a shine to.

Stylistically, the movie chiefly consists of three kinds of scenes. There is entertaining if obvious satire about Hollywood vulgarians (Shalhoub — who played the cabdriver in the underrated Quick Change — and Lerner are both very funny and effective). There are extended mood pieces involving the heat, solitude, and viscousness (peeling wallpaper with running, semenlike glue) of Barton’s seedy hotel room, with frequent nods to Eraserhead as well as Polanski and many repeated, obsessive close-ups of both Barton’s portable typewriter and a tacky hand-colored photo of a bathing beauty framed over the desk. Finally, there are the scenes between Barton and Charlie, all of which occur in Barton’s room (no other room in the hotel is ever seen) and suggest a sort of sweaty homoerotic rapport somewhat reminiscent of Saul Bellow’s novel The Victim and the tortured male bonding in Miller’s Crossing.

There’s a certain temptation to follow Barton Fink simply as a midnight movie, a string of sensations that alternates among styles and moods like a kind of vaudeville. As the plot suddenly veers into outright fantasy and metaphor, incorporating other styles and moods (mainly those of arty horror films), the effect of putting one damn showstopper after another is to almost obliterate any sense of logical narrative. (Moviegoers who don’t want their surprises spoiled should check out at the end of this paragraph.) We’re essentially invited to take a fun-house ride through these effects rather than ponder too much what they’re supposed to mean. But however much it appears to profess otherwise, Barton Fink is as heavily laden with “messages” as any Stanley Kramer film. Almost all of these messages, I should add, are cynical, reactionary, and/or banal to the point of stupidity.

As I see it, the messages are as follows:

(1) Socially committed artists are frauds. Admittedly, the only one we see is Barton Fink, but the film has no interest in showing us any others. The principal model for Fink appears to be Clifford Odets (although he’s given a George S. Kaufman haircut), and the film is at pains to show us that his ideas are trite, self-centered, and so limited that he ends both Bare Ruined Choirs and his wrestling-picture script with virtually the same corny line. We have no way of knowing whether he’s genuinely talented or not, and the movie seems completely uninterested in exploring this question, except for suggesting briefly that the people who praise his play are lunkheads. When the U.S. suddenly enters World War II toward the end of the movie, it seems not only to catch him completely unawares but to leave him indifferent as well — certainly not the reaction of the socially committed artists the Coens appear to be modeling him after. (As a friend has pointed out, Barton’s preoccupations are about a decade off; by 1941, proletarian leftist artists were talking about fascism and the war, not about lower-east-side fishmongers.) He’s an infantile sap throughout, and the movie forces us to share his consciousness in every scene.

2. Genuine artists like William Faulkner are frauds too — at least partially. It’s true that Mayhew is meant to suggest Faulkner rather than duplicate him, but consider how the Coens have loaded their deck. Mayhew looks like Faulkner, and he has both a “disturbed” offscreen wife with the same name as Faulkner’s disturbed wife (Estelle) and a secretary (Audrey) modeled in certain respects on Meta Carpenter, the script girl Faulkner was involved with. On the other hand, Faulkner was a taciturn drunk while Mayhew is a loquacious loudmouth who’s successively humming and belting out “Old Black Joe” both times we see him and spouts flowery rhetoric at every opportunity. Although the Coens claim not to have known this until after they wrote their script, Faulkner actually worked on a Wallace Beery wrestling picture when he first came to Hollywood (John Ford’s Flesh, 1932), and while it’s conceivable that Carpenter or other friends could have helped to write some of his scripts, the suggestion that Carpenter may have helped to write some of the novels is ridiculous and was invented for this movie only to suggest that Mayhew, like Fink, is a poseur who can’t really deliver the goods. Certainly the Coens have every right to twist reality as they please, but their alterations (“Old Black Joe”?) are so crass that they tend to rebound. Considering that most audience members won’t be closely acquainted with Faulkner, it’s disturbing that the only point at which Mayhew and Audrey diverge incontrovertibly from their models is when both of them become victims of a mad serial killer. (Audrey “gets hers,” in classic puritanical slasher style, just after she’s had sex with Barton.)

3. Hollywood producers are frauds. As indicated above, Lipnick and Geisler are hilarious, but the laughs are easily come by, and they make it difficult to see how such people could have turned out any pictures at all, much less several beautiful ones. (For whatever it’s worth, the first “Wallace Beery wrestling picture,” The Champ [see below], was arguably one of King Vidor’s masterpieces and won Beery, who actually played a prizefighter in the film, an Oscar.) Perhaps the Coens are justified in calling attention to Hollywood bigwigs as illiterate vulgarians, but judging from an early script of Barton Fink that I happen to have read, they themselves don’t even know how to spell such words as “choir,” “playwright,” and “tragedy.” In short, the rhetorical power of commercial moviemaking, available to anyone with a few million dollars to spend, allows them a free ride over a lot of people’s corpses — Louis B. Mayer’s as well as Faulkner’s and Odets’s — a ride that made me slightly nauseous.

4. The very notion of the “common man” is fraudulent. Charlie is introduced to us as the embodiment of this cliché, and Goodman’s wonderful performance manages to encompass it without ever seeming hackneyed. But the way the movie undermines the common-man cliché is by dragging out a contemporary countercliché that’s every bit as hackneyed. When Charlie turns out to be the serial killer, we are offered the revelation that people who chop off other people’s heads are nice, ordinary people just like you and me — “common” folks, in fact. (This cliché is promulgated in the news as well as in movies — take those interviews with junior high school teachers about how “nice” the killers seemed to be. Mysteriously, each time the homily is trotted out, whoever’s using it — in this case the Coens — seems to think it’s brand-new and profound.)

So judging from Barton Fink, what is it the Coens do believe in? Friendship, perhaps. Also, perhaps, an abstraction that the movie designates repeatedly as “the life of the mind” and that it associates with the act of creation — Barton’s mind and act of creation in particular — as well as with Charlie himself. (Barton’s room is clearly meant to suggest a brain, oozing fluids and all, and Charlie’s climactic reappearance when the movie suddenly goes metaphorical — walking down the hotel corridor with a shotgun while the rooms on both sides of him successively burst into flames — is accompanied by his vengeful declaration, “I’ll show you ‘the life of the mind!'”)

In order to follow the Coens’ shift from one metaphor to another, the wanton abandon of midnight-movie viewing becomes necessary — it might even help if you’re half asleep. Ironically, Goodman’s Charlie, the most multiple of all the film’s metaphors, also proves to be the only real character. (Turturro’s Barton seems much too simpleminded to have ever written a successful play, and his so-called struggles with writer’s block, as depicted in the film, could easily have been dreamed up in Lipnick’s office.)

One way of sorting much of this out is to follow the provocative suggestion of Variety reviewer Todd McCarthy and assume that Charlie doesn’t exist at all, except as an emanation of Barton’s unconscious — the “common man” his blocked imagination is screaming for. This interpretation would make the overheard sobs (or laughs) in the next room, Charlie’s murderous impulses, and even the mysterious package Barton receives from Charlie all really emblems of Barton’s own tortured mind; significantly, Mayhew indicates that he associates the act of writing with pleasure while Barton replies that he associates it with pain. According to this scenario, Barton murders Audrey himself because he can’t bear to face the possibility of her creative mind coming to the rescue of his own on the wrestling script.

The only problems with this scenario are that it fails to account for how Barton finally breaks through his creative block — unless we view Audrey’s murder as the less-than-instantaneous catalyst — and that it fails to mesh coherently with some of the other metaphors in the movie. I’ve been told that Deutsch and Mastrionotti, the wisecracking anti-Semitic detectives on the killer’s trail who question Barton and are ultimately killed by Charlie (one of whom is dispatched with the epithet “Heil Hitler”), are meant by the Coens to represent the Axis powers. (I suppose that makes Lipnick — whom we last see dressed as a full-fledged Army officer — the United States.) But if this is the case, the historical and metaphorical imaginations of the Coens must be even more threadbare and confused than I imagined. In what sense, exactly, were Hitler and Mussolini trying to track down the common man — or the life of the mind — and bring him (or it) to justice? And in what sense did this common man or life of the mind that wound up killing Hitler and Mussolini sell insurance or chop off people’s heads?

A final point should be made about the broad, comic-book-style Jewish caricatures in the film — Barton, Lipnick, Geisler, and Lipnick’s assistant Lou Breeze (Jon Polito). Spike Lee was lambasted on the op-ed page of the New York Times and by Nat Hentoff in the Village Voice (among other places) for Jewish caricatures in Mo’ Better Blues that employed one of the same actors (Turturro), occupied only a fraction as much screen time, and were if anything less malicious than the caricatures in Barton Fink. So I assume the reason Lee was singled out for abuse and the Coens won’t be to the same extent is that the Coens happen to be Jewish. For whatever it’s worth — speaking now as a Jew myself — I don’t consider any of the caricatures in either movie to be racist in themselves, and it seems to me somewhat absurd that Lee should be criticized so widely for something that the Coens do at much greater length with impunity. Being white, having the minds of teenagers, and believing that social commitment is for jerks are all probably contributing factors to this privileged treatment.