From the Chicago Reader (April 14, 1989). — J.R.

HENRY: PORTRAIT OF A SERIAL KILLER

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by John McNaughton

Written by Richard Fire and McNaughton

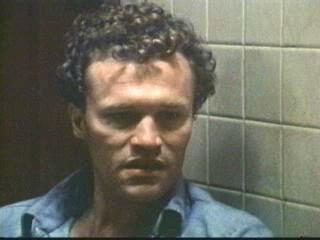

With Michael Rooker, Tracy Arnold, and Tom Towles.

Properly speaking, the slasher movie made its debut almost 30 years ago, with two features by middle-aged Englishmen, which coincidentally opened on separate continents within a few months of each other — Michael Powell’s Peeping Tom, which premiered in England in May 1960, and Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho, which opened in the United States three months later. The parallels between these two movies remain striking — especially their puritanical and voyeuristic underpinnings, which give us sexually repressed heroes whose morbid scopophilia (pleasure in gazing) leads directly to their brutal murders of women. And both occasioned critical protests of rage and disapproval when they first appeared.

But it was Psycho and not Peeping Tom that went on to launch a subgenre and receive exhaustive (and exhausting) analysis. And from the vantage point of the present, it is probably the shower murder of Psycho rather than the Odessa Steps sequence of Potemkin that has become the most chewed-over montage sequence in the history of cinema. But how much concrete edification has grown out of this close study? And isn’t there something a little disproportionate about the attention paid by our culture to this spectacle?

Although it took some time for a sufficient number of spin-offs to accumulate to give the slasher movie a name and identity of its own, the shadow of Hitchcock’s 1960 effort — significantly, his last feature in black and white, shot on the cheap with his TV crew — has been detectable in one way or another in all of them, for better and for worse. (Peeping Tom, an even more personal and self-reflexive work — and to my mind a more interesting one — has by contrast had a much more subterranean influence. It took two years to cross the Atlantic, it opened with virtually no fanfare — I originally saw it at an Alabama drive-in — and in contrast to Psycho‘s mainstream success, it has never garnered much of a reputation beyond its cult status.)

Psychomania is an obsessive, persistent legacy that warrants some uneasy reflection. The movie has never been one of my favorite Hitchcock pictures, but even if it were, I doubt that I would have looked forward with much enthusiasm to two sequels and dozens of strict imitations made over the next three decades. (For that matter, who would welcome as many direct rip-offs of Citizen Kane or Casablanca?) The public has an insatiable appetite for such imitations — from the relatively better ones by John Carpenter and Brian De Palma to countless others, mainly by more faceless directors. This appetite goes beyond even the popularity of sequels and cycles that already makes contemporary moviegoing an extended exercise in déja vu, or that makes the perennial revivals of favorites like The Wizard of Oz, Gone With the Wind, and Disney cartoon features a treasured national pastime.

Even more than these, the slasher movie suggests a kind of ritualistic repetition compulsion. It admits virtually no broadening or deepening of insight, and only minimal refinement of technique or content. It seems predicated simply on the desire of a mainly male audience to see women torn apart by maniacs, again and again, and preferably to see these attacks drawn out each time at some length. One might think that Hitchcock said it all back in 1960, but it’s a subgenre that has spawned entire cycles of sub-subgenres — all the Halloweens and Friday the 13ths and Nightmare on Elm Streets that have used essentially the same base ingredients (with supernatural elements added) for more or less the same ends, almost always less effectively. (A whole slew of other movies have been made about Ed Gein, the deranged mass murderer who inspired the Robert Bloch novel that Psycho was based on, ranging from documentaries to James Benning’s excellent experimental film, Landscape Suicide.)

Admitted, the cycle has also adopted a few post-Psycho cliches of its own, like the unexpected last-minute resurrection of the slasher-villain — a cornball standby that helped to seal the commercial success of Fatal Attraction in 1987, although its box-office enhancement of the current Dead Calm is more doubtful. But even in these cases, the example of Psycho is far from irrelevant: the staging of Fatal Attraction‘s resurrection in a bathtub surely refers us back to Janet Leigh’s shower-bath slashing in Psycho, just as the villain’s psychosexual hang-ups in the new release Dead Calm dimly echo Anthony Perkins’s dangerously repressed sexuality in Hitchcock’s film.

All this is to say that it is impossible for me to approach a contemporary slasher movie without a certain amount of animus. Unlike some of my colleagues who seem to believe that slasher movies are as natural, as viable, and as artistically defensible as musicals or westerns, I don’t look forward to them with pleasure. Above all, I resent the puritanism that seems central to their popularity. If Hitchcock had dared to photograph Janet Leigh (or her stand-in) naked in the shower without either his peekaboo montage or the grand spectacle of her being stabbed repeatedly, there surely would have been a moralistic outcry and a call for censorship that would have gone far beyond the objections raised to the film in 1960.

The fact that American violence in the real world is intimately intertwined with sexual repression might lead one to argue that slasher movies could offer some insight into this interrelationship; and indeed, critic Robin Wood has made this sort of argument at some length in such books as The American Nightmare and Hollywood From Vietnam to Reagan. To me, however, the simpleminded observations made about Anthony Perkins’s Norman Bates as a repressed mama’s boy in Psycho represent more or less the sum of these insights, and I’m sick and tired of hearing them endlessly repeated.

So I’m not exactly sure what it means to say that the 82-minute, Chicago-made independent feature Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer is the best slasher movie I’ve seen in several years. For one thing, I’ve deliberately missed many of its competitors; for another, I’m the sort of person for whom even “the best slasher movie ever made” wouldn’t constitute much of a recommendation — and Henry is certainly not as good a movie as Psycho. But its script, acting, and direction and its power to disturb and surprise nevertheless give it an undeniable distinction of sorts.

Financed three years ago by MPI Home Video of Oak Forest, and shot over a four-week period in 16-millimeter, Henry surfaced briefly at the 1986 Chicago film festival but has not been heard from since. After it was on the verge of being bought for theatrical release, the MPAA gave it an “X” rating for being “disturbing” (which it certainly is), reportedly without suggesting any cuts that would grant it an “R”; it has remained more or less in limbo ever since. Now it is being floated as a midnight movie for three consecutive Fridays at the Music Box, with midnight screenings in other major cities planned.

Offering us five separate corpses — four of them women — in its first five minutes, and at least seven more murders after that, Henry can’t be accused of any miserliness when it comes to gore. But one of its achievements is to make its graphic violence less disturbing than other elements in the film, such as the depiction of the two leading male characters, Henry and Otis, friends who met in prison.

The film opens by alternating shots of murder victims with scenes of Henry (Michael Rooker) cheerfully paying his check at a luncheonette, complimenting the waitress on her smile, cruising around Chicago and environs in his car, following one woman home, and later picking up a female hitchhiker. It isn’t until later that the film confirms that Henry is responsible for these murders, although the idea has already been suggested fairly strongly.

We soon learn that Henry is temporarily living with Otis (Tom Towles); another temporary boarder is Otis’s sister Becky (Tracy Arnold), who has just left her husband to come to Chicago, with the idea of sending for her daughter after she’s found work. We also learn that Becky formerly worked as a scantily clad dancer in a nightclub, and this being a slasher film, we immediately assume that this fact will be exploited later on. But interestingly enough, it isn’t; the only narrative importance that this has is that Otis seems fixated on her sexually, and his incestuous impulses are later complemented by the information that Becky’s father repeatedly abused her sexually when she was a teenager. (Henry, by contrast, behaves “like a gentleman” toward Becky, without any apparent sexual interest in her.)

One of the more awkward parts of Psycho is the final scene, when a psychiatrist proceeds to explain rather lamely the patterns in Norman Bates’s brain. Henry has a few perfunctory ideas of its own about what formed Henry, but at least it has the good sense to plant them fairly early on so that we can either refer back to them or dismiss them as we see fit. In an extended dialogue between Henry and Becky, we learn that Henry’s father lost both of his legs and that his late brother had a bone disorder that deformed him. Then Henry goes on to explain that he killed his mother at the age of 14 (although he remains vague and inconsistent about how this was carried out, apparently confusing her murder with all his subsequent ones): “She was a whore, but I don’t fault her for that. It ain’t what she done, it’s how she done it.” It emerges that she had sex with a lot of men in the house, when her husband as well as Henry were around; she used to dress her son up in women’s clothes and force him to watch her have sex with her boyfriends.

As an explanation, this paradoxically seems both overdetermined and insufficient; but once the movie proffers this information, it more or less drops the project of trying to explain Henry, and for the rest of the film he remains as much of an enigma as he was before. Indeed, the only apparent function of the story about Henry’s mother is to prevent us — as well as Becky — from asking further questions. The ineffable quality of Henry’s sickness is thus assumed rather than dangled in front of us as a false mystery.

After Otis witnesses two of Henry’s murders, he becomes an accomplice in future killing sprees, and in some respects emerges as a character even more terrifying than Henry. When the two of them wind up stealing a camcorder and a color TV from a person they have killed, the spectator’s own voyeurism is forced disturbingly into the foreground: they proceed to videotape some of their crimes, which Otis takes a particular pleasure in playing back and savoring, frame by frame. The sexual motivation behind most of these killings becomes increasingly apparent: Otis’s homosexual as well as incestuous impulses lead directly to some of the murders, while Henry’s own motivations, apart from his family background, are kept in the dark. (McNaughton was loosely inspired by the life of convicted killer Henry Lee Lucas, but whether McNaughton and coscreenwriter Richard Fire based some of their script on fact or speculation is unclear.)

In short, the script follows the characters’ grim and sordid exploits, but it doesn’t try to rub our noses in the seedier details simply for their own sake; the overall development of the plot is lean and purposeful. Similarly, while the gore in this film is often graphic, most of the murders take place offscreen; and even when they occur on-screen, there is never a sense of directorial showboating, as there is in Hitchcock; director and coscreenwriter McNaughton usually treats these details as functional parts of the narrative rather than as excuses for showing off. It is worth noting, however, that the film’s only stylistic invention is its use of aural flashbacks over some of the shots of corpses in order to suggest, however vaguely, what happened while the murders were taking place. Like another one of McNaughton’s stylistic signatures — camera movements that slowly approach the scene or result of a crime as if “closing in for the kill” — the purpose behind this device appears to be to implicate the spectator’s curiosity, imagination, and voyeurism in the same sickness shared by the killers (as in Peeping Tom), which is undoubtedly part of what makes the film so upsetting.

“It’s always the same and it’s always different,” Henry remarks to Otis at one point about his killings; the same comment might apply to slasher films and the kinds of violent misogyny that they invariably expose and reflect. Whether these films are exposing a certain kind of sickness or wallowing in it may prove to be a moot point in the long run. Henry seems to be doing both, but practically speaking the difference between exposing and wallowing may be mainly academic. Yet insofar as knowing what you’re doing makes a difference, Henry is a slasher movie with integrity, intelligence, and craft.