From the September 3, 1999 Chicago Reader. It seems worth reposting because, I’m happy to report, both these films are now available on DVD. — J.R.

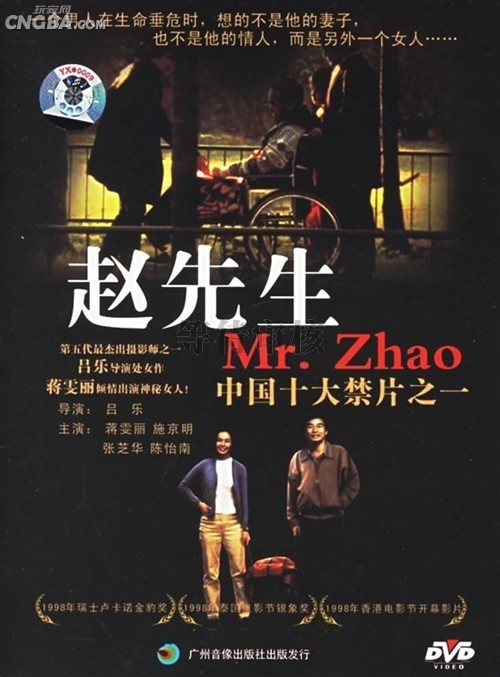

Mr. Zhao

Rating *** A must see

Directed by Lu Yue

Written by Shu Ping

With Shi Jingming, Zhang Zhihua, Chen Yinan, and Jiang Wenli.

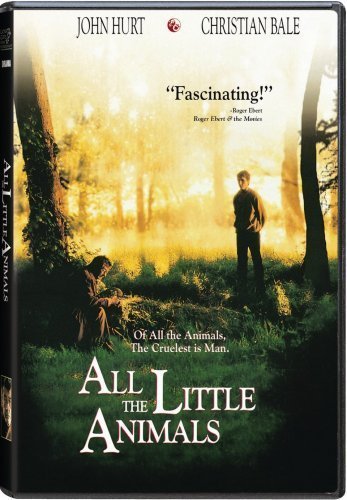

All The Little Animals

Rating *** A must see

Directed by Jeremy Thomas

Written by Eski Thomas

With John Hurt, Christian Bale, Daniel Benzali, James Faulkner, and John O’Toole.

Two of the best movies of 1998 are opening in Chicago this week — which makes them two of the best movies of 1999 — but the odds of either making much of a splash are just about nil. For one thing, they don’t appear to have opened previously anywhere else in the U.S., ruling out any advance buzz. For another, the budget for publicity in both cases appears to be about 15 cents; by contrast, the advertising budget for Austin Powers: The Spy Who Shagged Me was between $35 million and $40 million, not counting the Time Warner tie-ins (the entire production budget was $33 million). As a consequence, information about both films is hard to come by — I can’t even determine whether the screenwriter of Mr. Zhao is male or female.

Mr. Zhao is the directorial feature debut of Lu Yue, one of the best cinematographers in mainland China, whose credits include the recent films of Zhang Yimou and Joan Chen’s Xiu Xiu: The Sent Down Girl as well as earlier features by Tian Zhuangzhuang, Yim Ho, and Liu Guochang. His only previous film as director is a documentary made for French TV, Nujiang, the Lost Valley (1987), and he scouted locations for Joris Ivens and Marceline Loridan’s masterpiece A Tale of the Wind (1988). Mr. Zhao premiered at Locarno last year, where it won the top prize, the Golden Leopard, and I cited it near the beginning of my ten-best list in the Reader. Just about everyone I know who’s seen it considers it the best Chinese film of the past year or so. It’s of major importance in the history of Chinese movies, but because it has no distributor, it has opened practically nowhere and remains virtually unknown even in such cultural capitals as Paris and New York. That Facets Multimedia Center is apparently giving the U.S. theatrical premiere is a major coup.

All the Little Animals, the directorial debut of Jeremy Thomas — the producer of major films by Bernardo Bertolucci, David Cronenberg, Nagisa Oshima, and Nicolas Roeg, among others — surfaced at Cannes last year, eliciting a mainly favorable review from Variety‘s lead reviewer, Todd McCarthy, but apparently not much else. The most its low-energy distributor, Lions Gate, can offer the press is a “preliminary” press kit, which doesn’t even mention that the screenwriter, Eski Thomas, is related to the director. (I happened to find out that they’re married. Jeremy Thomas is also related to two highly commercial English directors of a previous generation: he’s the son of Ralph Thomas, who directed the popular Doctor at Large and its countless spin-offs, and the nephew of Gerald Thomas, who specialized in Carry On comedies.)

Mr. Zhao and All the Little Animals provide direct evidence that there’s no correlation between quality and the extent of advertising and media coverage–and they’re far from the only examples of the sort of thing that routinely escapes the radar of the mainstream media.

I describe Mr. Zhao as a major event in the history of Chinese movies because it marks a paradigmatic shift — not only in Chinese movies but perhaps also in what might be termed Chinese consciousness. About a quarter of a century ago I learned that there’s no word for “privacy” in Chinese. Assuming that this is still the case, Mr. Zhao suggests that it probably won’t be for much longer, because it explores and exposes private feelings in a manner that’s familiar in the West but unprecedented in Chinese movies. A serious comedy about adultery set in Shanghai, it amply demonstrates that the globalization of the world economy is having substantial psychological effects on Chinese life and art — by which I mean not a boom in Kentucky Fried Chicken franchises but substantial changes in the public ways people think, act, and experience one another. The complex behavior in this movie is recognizable, even familiar to Westerners, yet the actors and direction keep it perpetually fresh and volatile.

This movie carries the visible influence of John Cassavetes in its adroit handling of actors, its raw shooting style, the size of the emotions expressed, and its refusal to impose moral hierarchies on the characters. In no way are the title hero and his sexual hypocrisy excused, but the movie is too warm and complex in its understanding of all its characters to depict him as a simple villain — or to show either his wife or his mistress as simple victims of his chicanery. At least part of the performances and dialogue and apparently most of the camera work were improvised, and the acting of all five leading players is truly remarkable.

Most of the story unfolds in extended scenes in which the middle-aged title hero (Shi Jingming) — a university professor of traditional Chinese medicine who sells and administers some of his treatments as a sideline — is confronted first by his wife (Zhang Zhihua) when she discovers he’s been unfaithful, then by his young lover and former student, Tian Jing (Chen Yinan), when she announces she’s pregnant. (There’s a significant class difference between the wife, a factory worker who speaks a Shanghai dialect, and the better-educated lover, who, like the hero, speaks Mandarin.)

In these two sequences, composed mainly of extremely long takes, Zhao tells his wife that he intends to end his affair and tells his lover that he intends to end his marriage — leading to a comic, climactic third sequence in which both women confront him at a tea-shop meeting arranged by the wife. I won’t recount the remainder of the plot except to note that it’s somewhat awkward in terms of storytelling yet purposeful in developing the hero’s character as well as unexpected.

It’s characteristic of the film’s method that long sequences follow each other without transitions or narrative hinges of any sort, and the stark juxtapositions heighten a potent contrast between the encounters in each segment. Passing directly from the acrimonious responses and questions of the wife to the initially playful though eventually petulant responses of the mistress is something of a jolt, but the husband’s evasiveness with both women provides continuity as well as comic contrast.

I don’t believe I’ve ever encountered the psychological richness of these three characters — as well as of a male friend of Tian Jing’s and another young woman who turn up later — in Chinese cinema. It’s almost as if director Lu Yue, who apparently spent several long periods in France between 1987 and 1992, used tenets of Western dramaturgy to delve into aspects of the personalities of his characters that couldn’t otherwise be singled out and studied. The resulting film feels pure and authentic, not like some artificial cultural hybrid, so I’m prone to regard it as a marker of a current historical change in the urban life of mainland China.

If Mr. Zhao, like much of the optimism of contemporary Asian culture, points toward the 21st century, All the Little Animals is a no less striking throwback to Charles Dickens’s 19th century in terms of its alarmist melodramatic impulses. Based on the only novel written by the late Walker Hamilton, which Thomas reports he read and first wanted to film in the early 70s, it conjures up a world in which goodness and evil are still pure and unquestioned essences, making the presence of heroes and villains equally unambiguous and uninflected. To accept this movie at all requires an acceptance, even a cultivation, of innocence. If it belongs anywhere it’s alongside D.W. Griffith’s Broken Blossoms and Charles Laughton’s The Night of the Hunter — not because it’s as good as they are (few things are) but because it looks at the world with a comparable metaphysical simplicity. If I’m not mistaken, Thomas acknowledges the connection with The Night of the Hunter — a movie steeped in Griffith’s influence — in a brief, beautiful flashback: floating down a river in a boat cradling a fox in his arms, Bobby (Christian Bale), the childlike hero, glides past a magical spider’s web.

Something in me strongly resists this kind of hokeyness, but if I can digress for a paragraph, I’ll admit that the recent sliming of the fans of The Blair Witch Project has made me more disposed than usual to defend callow innocence in movies. The young audience for this movie isn’t as cynical and jaded as the media expect them to be: in defiance of the studios and the cult of special effects, they’ve spontaneously responded to a minimalist low-budget movie that recognizes their own ignorance and isolation from the world at large, making an allegory out of that vulnerability and using the spectator’s imagination as its principal paint box. This is a cruder but no less authentic version of the Val Lewton horror features of the 40s. Yet cover stories in Time and Newsweek have insisted on attributing its success simply to Internet marketing, while a couple of leftist reviewers have credited it to the appeal of a misogynist fable about what happens when you place a woman in charge of a film crew. These and other analyses seem to insist that the young viewers are responding only out of automatic reflexes and insatiable capacity to consume. I prefer to believe they’re recognizing and acknowledging their own innocence. Admittedly, this innocence comes in many forms –from that of viewers who believe Blair Witch is a documentary to that of people who merely identify with the confusion of three characters who get lost in the woods (I happen to find the woman the most sympathetic of the three). Whatever the form, this innocence is the reverse of the cynicism of publicists and journalists.

Given the degree to which cynicism is currently in fashion, synopsizing All the Little Animals is tantamount to ridiculing it, but I need to offer at least a taste of the story to indicate the sort of suspension of disbelief that’s required. Bobby, the mentally challenged hero who narrates, is in his early 20s, but he’s been stuck with a child’s consciousness ever since he was in an auto accident as a kid. He’s an animal lover with an adoring mother who owns a London department store and an evil stepfather — Bernard De Winter (Daniel Benzali), whom he calls “the Fat” — and he cherishes a pet mouse named Peter that he keeps hidden in his bathroom. As the story opens, his mother has just died, and “the Fat” is trying to force him to sign over the department store, threatening to commit him to an insane asylum for life if he refuses; just to show how mean and determined he is, “the Fat” kills Peter.

Bobby buries Peter and runs away, hitching rides westward. When one truck driver tries to run over a fox, the horrified Bobby wrestles with him for control of the steering wheel. The truck overturns, and the driver is killed. At the site of the accident Bobby meets the eccentric Mr. Summers (John Hurt), whose life’s work has been to collect and bury animals run over by cars, showing a complete indifference to the drivers and a deep devotion to all living things preyed upon by humans. Bobby eventually persuades Summers to let him assist in this mission, and the two of them settle down to an idyllic life in the forest in a simple cottage, sustained by a substantial amount of money Summers has from an earlier career in a bank — until Summers decides they should travel to London and settle accounts with Bobby’s stepfather.

“I long for a little naivete, but there’s none around,” the highly cynical filmmaker Rainer Werner Fassbinder remarked in an interview in the 1970s; a comparable sentiment apparently goaded Thomas into making this willfully innocent movie. You might suppose that he was trying for a hit PC tearjerker like Rain Man or The Eighth Day, but his movie is far too sincere and poetic to make this plausible. The beautiful feeling for the landscapes, which are powerfully shot by Mike Molloy, only amplifies the heartfelt nature of the project.

Indeed, the opening sequence reveals a curious ambivalence toward conventions that seems to rule out cynical deliberations. A slow pan across a landscape as Bobby narrates offscreen eventually leads to the figure of Bobby, a traditional trope — but it’s Bobby speaking directly to the camera, which is highly unorthodox. After this the movie sticks mainly to traditional storytelling, apart from a few poetic interjections, such as the hommage to The Night of the Hunter cited above; the adoption of 19th-century-melodrama conventions seems motivated mainly by a desire to tap into the emotional intensity they offer. I was enthralled by these tactics, but some viewers might gag. (The two “user comments” about this film I found on the Internet Movie Database are about as far apart as one could imagine: a long paragraph headed “Best Movie I’ve Seen This Year” and a pithy put-down beginning “Very very bad. Paper thin characters, tired plot, absurd villain, ludicrous in every way.”)

It makes perfect sense to me that a Western filmmaker in the late 20th century should be moving backward, seeking to return to the emotional directness and purity of a D.W. Griffith, while an Asian filmmaker should be using the example of Cassavetes, a more contemporary and relevant exemplar of emotional directness and purity, to move forward. In this corner of the globe we’ve obviously lost something when it comes to expressing feelings simply, strongly, and without embarrassment, and part of what moves me about All the Little Animals as a throwback to the Griffith tradition is the primal power it unleashes — despite an overly protracted suspenseful climax that shows a certain amount of strain, the narrative kept me glued to my seat. (Like Mr. Zhao, it loses some of its clarity of purpose during the final act.) It reminded me of the era when people believed in what they saw at the movies — in heroes who were unambiguously good and villains who were so evil their rank behavior required no explanation. In contrast, it’s the healthy skepticism about such matters and a relatively nuanced sense of psychology that seems fresh in Mr. Zhao. Maybe that’s because mainland China still has a world of interiority to discover; we seem to have more interiority than we know what to do with.