From the Chicago Reader (March 12, 1993). — J.R.

VAN GOGH

*** (A must-see)

Directed and written by Maurice Pialat

With Jacques Dutronc, Alexandra London, Gerard Sety, Bernard le Coq, Corinne Boudon, and Elsa Zylberstein.

Consider the following two scenarios:

(1) In May 1890, Vincent van Gogh, missing one ear, arrives at Auvers-sur-Oise and meets Dr. Gachet — an avid art collector and fan of the Impressionists contacted by Vincent’s brother Theo — who advises the painter not to worry about his nervous attacks and to concentrate on his work. Taking a room at the Ravoux inn, Vincent follows the good doctor’s advice, but his alienation from others continues to torment him; during Bastille Day, when everyone else is celebrating outside, he sits alone inside, in extreme anguish, at a cafe table. While painting a field he is attacked by crows, and he agitatedly adds a few of these birds to his canvas before pulling out a revolver and shooting himself. He dies shortly afterward, his faithful brother at his bedside.

(2) In May 1890, Vincent van Gogh, both ears intact, arrives at Auvers-sur-Oise, takes a room at the Ravoux inn, and meets Dr. Gachet — an avid art collector and fan of the Impressionists contacted by Vincent’s brother Theo — who advises the painter not to worry about his nervous attacks and to concentrate on his work. Vincent follows this advice, painting the doctor’s teenage daughter Marguerite (who soon develops a crush on the artist), the doctor himself, several local landscapes, and even the village idiot, at his request, for the price of two sous. He meets friends from Paris at a riverside gathering and makes love there to Cathy, a prostitute he knew at Arles. (Later she expresses concern about his former self-mutilation, and he explains that he merely nicked one of his ears a little.)

Theo, his wife Jo, and their baby come to visit Vincent and the Gachets for the day, and they all enjoy an outdoor meal — Vincent amuses everyone with his Toulouse-Lautrec imitations, and the female servants sing — and a riverside dance. After telling Jo that he’s been a financial burden to her and Theo, Vincent jumps into the river, but he’s quickly fished out and Theo affectionately chastises him for his silly behavior.

Soon after, Marguerite comes to Vincent’s room and unbuttons her blouse; later in the day we see them making love in the fields. (Still later, she calls her father a fake liberal and coward for not approving of her affair with Vincent.) Visiting Theo and Jo in Paris, Vincent attacks his brother for not trying to sell his paintings. Theo attacks him in turn for insulting a critic who’s written about his work, and, after Vincent leaves for a brothel and cabaret, Jo attacks Theo for supporting Vincent. When Marguerite turns up looking for Vincent, Theo takes her along to the brothel, where she spends much of the night dancing and making love with Vincent. But on the train ride back to Auvers she denounces Vincent as sick, and Dr. Gachet, who meets them at the station, calls him loathsome before Marguerite accuses her father of not loving her and then faints. Vincent has sex once again, this time with a woman at the inn, goes out in the fields to paint, and winds up shooting himself. He dies shortly afterward, his faithful brother at his bedside.

The first of these scenarios describes the last reel or so of Vincente Minnelli’s 1956 MGM feature Lust for Life; the second describes, in abbreviated form, Maurice Pialat’s 1990 French art movie Van Gogh. If the second scenario strikes you as somewhat ludicrous given what we know about van Gogh — in particular about his sex life in May, June, and July 1890 — your reaction apparently isn’t shared by most of the French, English, and American critics who’ve written about the film since it premiered in Cannes 100 years after van Gogh died. They seem to find it a perfectly plausible account of the last nine and a half weeks of his life.

Yet the letters the painter wrote to his brother in his last 67 days — which take up the last ten pages of a collection edited by Irving Stone (author of the novel Lust for Life) in a book called Dear Theo — tell a different story. There are many references to Dr. Gachet, and even more to Paul Gauguin (who’s not mentioned once in Van Gogh), but the only references to Marguerite Gachet are as follows: “I shall most probably do the portrait . . . of [Gachet’s] daughter, who is 19 years old.” “Yesterday and the day before I painted Mademoiselle Gachet’s portrait, which you shall soon see, I hope; the dress is red, the wall in the background green with an orange spot, the carpet green with a red spot, the piano dark violet. It is a figure that I painted with enjoyment — but it is difficult. . . . Dr. Gachet has promised to make his daughter pose for me another time with the small organ. And perhaps I shall have a country girl to pose too.” Lawrence and Elisabeth Hanson in Passionate Pilgrim: The Life of Vincent Van Gogh refer to Marguerite by name only once, informing us that Vincent “made a study of Marguerite Gachet at the piano that brought a cry of ‘Admirable!’ from Theo.” (In Van Gogh, it is Dr. Gachet who has this reaction.)

While one would ordinarily expect the Hollywood biography of van Gogh to “clean up” the mess of his life and the French art-movie version to wallow in it, something close to the reverse happens. Minnelli’s movie even takes the trouble to eliminate some of the Hollywood-ish obfuscations in Stone’s novel — most significantly, a phantom lover assigned to van Gogh. (Robert Altman’s Vincent & Theo, one should add, seems about as serious as Minnelli’s movie in sticking to the historical record.)

In defense of his own fanciful (and very Frenchified) account of van Gogh’s last 67 days, Pialat has said, simply and infuriatingly, “[One doesn’t] produce 100 masterpieces in a state of depression — van Gogh died from having had a glimpse of happiness.”

Pialat is one of the finest living French filmmakers, and Van Gogh, his tenth feature, is arguably one of his best — certainly, at two and a half hours, one of his most ambitious. I still have a sneaking preference, however, for certain earlier Pialat works — I’m thinking especially of We Won’t Grow Old Together (1972), The Mouth Agape (1974), and Passe ton bac d’abord (1979) — over his more top-heavy art-house exertions like Loulou (1979) and Under the Sun of Satan (1987). But given the economic inflation we’ve all come to take for granted, maybe we should allow Pialat his aesthetic inflations, Van Gogh included.

The late Stephen Harvey wrote that Minnelli’s Lust for Life was the only MGM feature he initiated himself, and plausibly suggested that Minnelli’s desire to make the film came from a close identification with van Gogh. It seems to me likely that Pialat’s desire to make Van Gogh stemmed from a similar identification with the painter, even if it wasn’t accompanied by comparable scruples about portraying van Gogh’s life. Pialat was a painter for 20 years before he turned to filmmaking, and his central theme is the male drive toward self-destruction. The sexual interest in nubile teenagers in some of his previous films, such as Passe ton bac d’abord and A nos amours (1983, see below), may help to account for the invented affair between Marguerite and Vincent in Van Gogh.

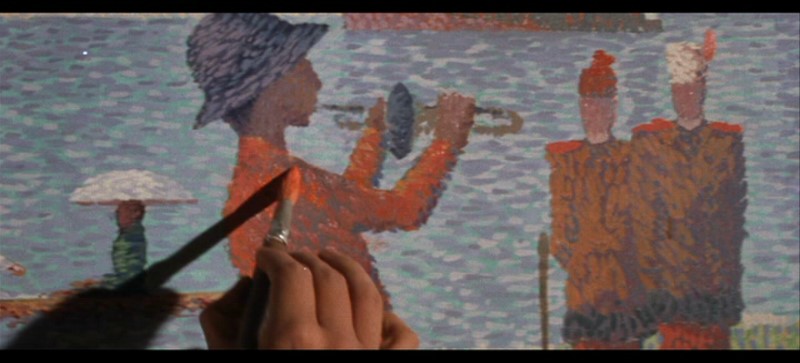

If one can forget about the real Vincent van Gogh while watching Van Gogh — not an easy matter, given the film’s title — there is a great deal to admire. The achievements of this film, which have practically nothing to do with Minnelli’s in Lust for Life, have a great deal to do with the subjects and the ambience of Impressionist paintings, and a branch of French cinema — specifically the one associated with Jean Renoir — that is often identified, for better or worse, with this movement. From the moment that Vincent (Jacques Dutronc) emerges from a third-class car in the Auvers-sur-Oise train station, a world and an era are powerfully realized, and the leisurely pacing of the action allows us to savor this creation in many details.

Minnelli’s stylistic debt to van Gogh is almost exclusively a matter of expressionism — in his efforts to represent the painter’s emotions through the actors’ performances (especially those of Kirk Douglas as van Gogh and Anthony Quinn as Gauguin) and through the colors, compositions, and camera movements of his mise en scene. Pialat’s more naturalistic and exploratory camera style, largely derived from the 30s films of Renoir, describes a kind of wandering investigation of events and locations played over a subdued acting style, which seems indebted more to Robert Bresson than to Renoir. It’s a style that plays on the actors’ physicality rather than on their expressiveness; significantly, Bresson (also a former painter) refers to his actors as “models.”

While some of the sequences set on the river recall scenes from such 30s Renoir films as Boudu Saved From Drowning and A Day in the Country, and part of the lengthy brothel sequence recalls Renoir’s 1955 French Cancan, the most extended literal citation I’m aware of is a lengthy dance sequence (here set in a brothel) that comes from John Ford’s 1948 Fort Apache. What this has to do with van Gogh or Impressionism — or naturalism, for that matter — is anyone’s guess.

Even if one can’t forget about van Gogh while watching Van Gogh, the film still has a lot to say, especially about the intractability of artists and their difficulty in living in society. The lengthy scenes by the river and in the brothel, as well as many other scenes set in the inn bar, the Gachet household, and Theo’s apartment and gallery, celebrate communal interaction and shared experiences — a central subject of Renoir’s films as well as Ford’s — and the irruptions of van Gogh’s solitude or madness in these densely interwoven worlds are striking mainly because they’re so uninflected. The point is that it’s easy to overlook — or rationalize, or attempt to assimilate — these irruptions rather than understand them on their own terms, and the power of Pialat’s mise en scene comes from placing them in such a way as to suggest how irreconcilable van Gogh’s vision was with the world in which he lived.

The decision to give van Gogh a healthy sex life may seem ridiculous considering the real circumstances of his life — so ridiculous, indeed, that when Vincent lies wounded on his deathbed I was reminded more of Bob Fosse’s All That Jazz than of Renoir or Ford. But it still creates a zone of distraction for us and for the film’s characters that meshes logically with Pialat’s overall purpose, which is to show us how much sex, meals, conversation, dancing, and all the other daily pastimes that form this film’s busy surface ultimately interrupt the lonely and all-consuming confrontation that takes place between artists and their work.

Published on 15 Aug 2011 in Featured Texts, Featured Texts, by jrosenbaum