From the January 1973 issue of the short-lived Saturday Review of the Arts. — J.R.

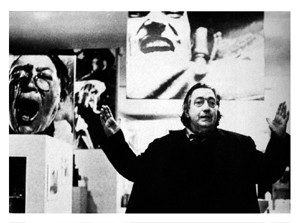

Henri Langlois’s latest creation, the Cinema Museum in Paris, finally opened last summer, a year and a half behind schedule. Only a few of the exhibits were labeled, and five months later the long-awaited catalogue of the exposition has not yet appeared. But even in its present state, the Cinémathèque Française is already the most influential film archive in the world.

Langlois’s “Seventy-five Years of Word Cinema” occupies sixty rooms in the curving promenade of the Palais de Chaillot, directrly across the Seine from the Eiffel Tower; the present exhibit represents less than one-tenth of the Cinémathèque’s collection of movie memorabilia. From the beginning, the Turkish-born film historian has tried to save everything: to impose selective criteria, he believes,is to anticipate the critical standards of the future. If the result is a cross between a crowded attic and a carnival funhouse, with all its calculated effects, this approach also permitted such young critics as Jean-Luc Godard, Jacques Rivette, and François Truffaut in the 1950s to take crash courses in every kind of cinema before making their own movies.

The vision of the Cinémathèque’s founder encompasses both Marilyn Monroe and Eisenstein; stray souvenirs and essential artifacts are given equal prominence. As visitors pass through the German Expression sets of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, they discover a blown-up picture of Nosferatu, the original German Dracula, lurking behind one of the slanted doorways. In a dark passageway celebrating the early talkies, an illuminated city set from Broadway Melody twinkles over sheet music of the same period and scripts of Scarface and Street Scene, while a passionate love scene from King Vidor’s Hallelujah is projected on a small screen. In a glaring red alcove, the paranoiac intensity of Ivan the Terrible is evoked in Eisenstein’s pre-production sketches, while Cocteau’s Beast (from Beauty and the Beast) stands sentry just outside.

The museum’s labyrinthine progression is roughly chronological, beginning with magic lanterns, panoramas, and other optical toys of pre-cinema and culminating in a vast mélange that represents the last twenty-odd years of film. You come on Edison’s first motion-picture camera; whole rooms devoted to such pioneers as Louis Lumière and Georges Méliès; a miniature replica of the Pathé Studio in 1905; Eric von Stroheim’s Prussian uniform; a campy self-portrait by Asta Nielsen, the Danish silent star, fashioned out of scraps of the dresses she wore in her films; a cubist Charlie Chaplin constructed by Fernand Léger and used in his Ballet Mécanique in 1924; the robot Maria from Metropolis; sets and posters of René Clair’s A Nous la Liberté; production designs for Citizen Kane; brightly colored cartoon sketches by Fellini of Giulietta Masina in La Strada and Nights of Cabiria; the score of An American in Paris, annotated by Gene Kelly when he blocked out the ballet sequence; two of Deklphine Seyrig’s Dior dresses from Last Year at Marienbad; and a beggar’s coat worn in Kurosawa’s latest film, Dodeskaden.

Many of the costumes, such as Jean-Louis Barrault’s harlequin outfit from Children of Paradise, are laid out to suggest ghostly apparitions of the actors who wore them. Near the end of the show, you discover James Dean’s red zipper-jacket cradling the script of Rebel Without a Cause and rubbing shoulders with Jean Yanne’s fur-collared jacket from Le Boucher, which clutches a handwritten scenario of the Chabrol film in an empty sleeve. Close by are an evening gown from Lola Montès and, stretched out on a luxurious divan, a dress worn by Marilyn Monroe in Let’s Make Love. Beyond that, down the steps, and into the Cinémathèque’s basement auditorium — where five films are shown daily at nominal proces (80 cents per film, 60 cents for students) — you arrive at the giant movie screen, the source of all these dreams and phantoms.