From the Chicago Reader (April 22, 1994). — J.R.

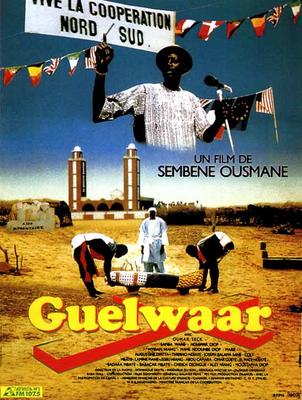

*** GUELWAAR

(A must-see)

Directed and written by Ousmane Sembène

With Omar Seck, Mame Ndoumbe Diop, Thierno Ndiaye, Ndiawar Diop, Moustapha Diop, Marie-Augustine Diatta, Samba Wane, and Joseph Sane.

We like to think that the essential works of any art form are readily available to everyone; but when it comes to film we still aren’t within hailing distance of that goal, even if we agree to the debatable proposition that a film’s transfer to video equals its availability. The canons of film history taught in film departments across the country are based almost entirely on the titles that film, video, and laser disc companies choose to place or keep on the market, which is all that most film professors have seen in the first place. And now that 16-millimeter film distribution is already on its last legs, the history and breadth of the medium, even for most film students, is quickly being reduced to what can be found at local video stores.

Among the many key items that can’t be found there are virtually all the major African films, including the seven features and four shorts of Senegalese writer-director Ousmane Sembène, by most accounts the greatest African filmmaker. Sembène’s films can be rented in 16- and 35-millimeter, most often in less-than-ideal prints, from New Yorker Films but nowhere else. None of them has been issued on video, and New Yorker has no plans to do so. Sembène’s films, along with the great middle-period masterpieces of Nagisa Oshima (including Death by Hanging, Boy, The Man Who Left His Will on Film, The Ceremony, and Summer Sister), Jacques Rivette’s Celine and Julie Go Boating, and the complete works of Jean-Marie Straub and Daniele Huillet — to cite only the first examples that spring to mind — are lost to American culture mainly because Dan Talbot, who runs New Yorker Films, has determined that more money can be made by distributing these works in battered prints to a few select venues than by issuing them on video. And because our culture supports such reasoning, and rejects the notion that public funds should be used to make such work available in any form, Sembène’s work unintentionally and grotesquely becomes the caviar of cinema when by all rights it should be treasured as the meat and potatoes.

Guelwaar, for instance — which is about the separate, if interlocking and interdependent, Christian and Muslim communities in a Senegalese town — presents the most detailed and knowing treatment of tribalism I’ve seen in any film of the 90s, and it offers the most blistering attack on the ethics, administration, and effects of foreign aid I’ve ever seen. Both subjects are treated comically as well as tragically, and in so deftly spelling out their precise African and Senegalese inflections Sembène gives them universal significance as well. If you want to understand the way an African village works, take a look at this one. And if you want to understand how the world at large works, you might try starting with an African village.

I’ve only managed to see three of Sembène’s features so far — Black Girl (1966), Camp de Thiaroye (1987), and Guelwaar (1992). All three have a novelistic richness of texture and fineness of detail that marks Sembène as a major writer as well as a master director, so it’s hardly surprising that his published work — which so far includes seven novels and two short-story collections, all written in French — is even more critically acclaimed than his films. In fact, Sembène’s major motive for becoming a filmmaker in the early 60s was his desire to reach more Africans than he could via the printed page. Six of his books have been translated into English since 1987: The Black Docker, God’s Bits of Wood, The Money Order (published with the short story “White Genesis”), Xala, The Last of the Empire: A Senegalese Novel, and Niiwam and Taaw: Two Novellas. (Sembène’s films The Money Order and Xala were based on his novels; working in the opposite order this time, he has reportedly completed a novel based on Guelwaar.)

Sembène was born in 1923 in Casamance, a region in southern Senegal, and raised as a Muslim. After his parents divorced he remained with his father, a fisherman, and left school in his early teens following a fight with a teacher who insisted that he sing the French national anthem. After working as a mechanic, a carpenter, and a mason and becoming active in the labor movement, he fought as an artillery soldier with French colonial forces in Africa and Europe during World War II. Then, following his participation in a major strike on the Dakar-Niger railroad in 1947-’48 (the subject of his best-known novel, God’s Bits of Wood), he emigrated to Marseilles, where he worked as a longshoreman and union leader — the subject of his first novel, The Black Docker, published in 1956. By the time he returned to Senegal in the early 60s he was already known internationally as a major African writer and his former devotion to Islam had been profoundly altered by his Marxist and socialist convictions. (His satiric yet affectionate treatment of both the Catholic and Muslim characters in Guelwaar is so evenhanded that, to my mind at least, his Islamic background can’t be detected.) After studying filmmaking at Moscow’s Gorki studio on a scholarship in 1962, he began making films in Africa while continuing to write fiction, this time in “incorrect” French with an increasingly Africanized syntax and inflection; five years later he became the first filmmaker ever to employ dialogue in Wolof, the principal language of Senegal, in The Money Order (1968), his second feature. Since then the languages spoken in his features have included Diola and French (in Emitai, 1971), French (in Xala, 1974), Wolof (in Ceddo, 1976), and French and Wolof in both Camp Thiaroye and Guelwaar.

These linguistic distinctions are important because a lot of what transpires in Guelwaar is based on cultural and ideological clashes occasioned by the speaking of French, the neocolonialist tongue used mostly by various officials, flunkies, and outsiders and not understood by many of the locals, instead of Wolof, the native tongue, indigenous but vaguely disreputable in the minds of the snootier characters. (To understand these clashes, it’s helpful to know that Senegal was a French colony for roughly a century and a half until it became independent in 1960; that its first president, who successfully ruled for 20 years, Leopold Sedar Senghor, was a major French-language poet and a Catholic who didn’t speak Wolof; and that Christians, nearly all of them Catholics, comprise less than 3 percent of the Senegalese population while Muslims comprise over 90 percent.) As the movie’s action repeatedly shows, the horrors and corruptions associated with both tribalism and foreign aid are inextricably tied up with these linguistic distinctions.

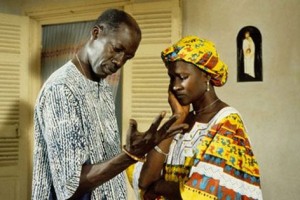

“Guelwaar,” which means “the noble one” in Wolof, is the nickname of Pierre Henri Thioune, a prominent member of the Christian community and a political activist opposed to both foreign aid and the misappropriation of public funds; we learn of his death — brought about by a mysterious beating — in the opening scene. He leaves behind a devoted wife, Nogoy Marie, and three of his original seven children who have survived to adulthood: an older son, Barthelemy, who lives in Paris; a younger son, Aloys, who lives at home and is unable to work due to an injury he sustained falling out of a tree as a child; and a daughter, Sophie, who provides the family with most of its income by working as a prostitute in Dakar. We learn in a flashback that although Nogoy Marie feels shamed by Sophie’s profession, Guelwaar felt it was less demeaning than having to depend on foreign aid.

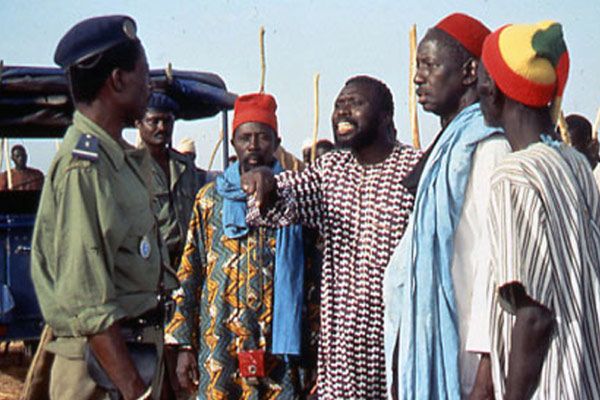

As various relatives and friends congregate in town for the funeral, the alarming discovery is made that Guelwaar’s body has disappeared. After Barthelemy reports this calamity to Gora, a local police officer — with obvious disdain for the bureaucratic confusion that would allow such a mishap to occur and an insistence on speaking only in French — Gora grudgingly brings him along in his jeep as he investigates. Eventually this leads him to the Muslim settlement outside of town, where he pointedly leaves Barthelemy back at the jeep while he goes to make inquiries about the recent burial of a man named Meyssa Ciss. It soon emerges that through a mix-up of death certificates, both drafted in French, compounded by the Muslim undertaker’s ignorance of French and the fact that he had to perform his work at night, without electric light, Guelwaar’s body was buried in the Muslim cemetery. The remainder of the movie charts the escalating tensions and misunderstandings that grow out of the attempts of Gora and the Catholic townspeople to dig up Guelwaar’s body and bury it in the Catholic cemetery.

The driving force behind Sembène’s narrative style is his didactic and passionate desire to impart information, and often polemical arguments, as quickly and efficiently as possible. Sometimes the polemics are so inherent to the story that the results are seamless: when critic Manny Farber placed the hour-long Black Girl in the number-one slot of his ten-best list for Artforum in 1969 — ahead of such films as My Night at Maud’s, The Wild Bunch, and Easy Rider — he wrote that “Sèmbene’s perfect short story is unlike anything in the film library: translucent and no tricks, amazingly pure, but spiritualized by a black man’s grimness in which there is not an ounce of grudge or finger-pointing.” A tragic and powerful account of what ensues when a Senegalese maid gets taken to the Riviera by her French employers, Black Girl is too confident throughout to register as polemical, though it might be argued that a certain amount of finger pointing is implicit in the original French title, La noire de . . . , which translates as “the black woman (or girl) of (or from, or belonging to) . . . ” The same thematic seamlessness is there in Camp Thiaroye, based on the real-life mutiny in 1944 of African soldiers in Senegal — who return from fighting with the Free French army to discover that they’ve been cheated out of their severance pay — that ended in their massacre. And if Sembène’s style becomes marginally less assured in Guelwaar, this may be because the number of things Sembène has to say, and the urgency with which he wants to say them, occasionally threatens to exceed what a single story can convey. The fact that at 71 Sembène is already planning other films, some of which he hasn’t yet been able to finance, helps explain his impatience.

This isn’t to imply that there’s anything programmatic or stiff about Guelwaar — only that more issues get exposed than the plot can fully negotiate or follow through on, so that they’re either dropped or provided with cursory resolutions. But along the way there’s some riotous comedy involving the various double standards that operate in both the Muslim and Christian communities. Meyssa Ciss, we soon discover, is little mourned by either of his wives, and the younger one is also tired of the affair she’s been having with his brother and eager to leave the village even if it means cutting short her mourning period. (She gets off one delightful tirade that reminds one of how central women’s rights are to Sembène’s politics.) Meanwhile, at the Thiounes’ house, the corrupt and Europeanized mayor (he owns a Mercedes) is protesting the presence and revealing dress of one of Sophie’s fellow prostitutes from Dakar, and Gora — the principal intermediary between the warring factions — is feeling harassed by the snobbish remarks of Barthelemy, whom the local Muslims disparagingly refer to as a white man. It’s a sign of Sembène’s wit that even the white men in the audience will get the point.

I’m wary of imparting any more of the plot of a picture whose evolving clarifications, most of them conveyed in brief flashbacks, are central to the force and lucidity of the story. But it’s worth remarking on the style of Sembène’s exposition, which stands in contrast to the style of most American and European movies, and which I think deserves to be called Homeric. In the first chapter of Erich Auerbach’s classic work of literary criticism, Mimesis, an extended stylistic comparison is made between The Odyssey and the Old Testament — specifically between the “flashback” account of how Odysseus received the scar on his thigh and the elliptical narrative treatment of the story of Abraham, which routinely omits important plot points and key visual details. Auerbach summarizes his analysis as follows:

“The two styles, in their opposition, represent basic types: on the one hand [in the Odyssey] fully externalized description, uniform illumination, uninterrupted connection, free expression, all events in the foreground, displaying unmistakable meanings, few elements of historical development and of psychological perspective; on the other hand [in the Old Testament], certain parts brought into high relief, others left obscure, abruptness, suggestive influence of the unexpressed, “background” quality, multiplicity of meanings and the need for interpretation, universal-historical claims, development of the concept of the historically becoming, and preoccupation with the problematic.”

There are certainly more than a “few elements of historical development and of psychological perspective” as well as “universal-historical” claims in Guelwaar (whose subtitle, incidentally, is “An African Legend for the 21st Century”), and “uniform illumination” doesn’t inform the entire movie. (We never are shown the actual beating that leads to Guelwaar’s death, for instance.) But the remainder of Auerbach’s description of the Homeric style seems strikingly apt. Each flashback that comes along to illuminate the past immediately clarifies the present; Sembène dives into past events in a wonderful no-nonsense manner whenever he wants to deepen or inflect our sense of what’s occurring in the present. This sense of the straight-ahead narrative — brimming with facts and observations, each of which has its special place in the overall composition — is apparent even when the film appears to be dawdling along with its characters, conveying the loping rhythms of African rural life with pleasurable ease. Let’s hope that whether or not Sembène’s movies wind up in video stores, this irresistible forward momentum will take him into the next century, where we’ll sorely need his kind of wisdom.

***

From the July 21, 1994 Chicago Reader:

Dear editor:

Jonathan Rosenbaum’s intelligent review of Guelwaar in the April 22, 1994, issue of the Chicago Reader contains a few gratuitous remarks about me and my company, New Yorker Films, which I cannot leave unattended.

New Yorker Films is charged with renting only 16-millimeter and 35-millimeter prints of [Ousmane] Sembène’s work and no video. He’s right, and this is a pity. I have been after Sembène for years to put his works out on video. He refuses to cooperate — and I cannot do it without his cooperation, let alone his approval — because he simply loathes video and does not want to see his films in the marketplace in video. If Jonathan had taken the trouble, as any competent journalist would have done, he would’ve gotten the straight dope. Instead, he chose to bum rap me, as if his role as a critic gives him special entitlement.

I do believe that Jonathan once wrote about the [Nagisa] Oshimas not being out on video. Since then, we have put two out — Cruel Story of Youth and The Sun’s Burial. We are hoping to do the others on video as soon as we are able to renegotiated our contract and the film will be going on video sometime in 1995.

As to the works of Jean-Marie Straub and Daniele Huillet, he’s got to be kidding. Would Jonathan like to be my partner in this venture? The fact that I still keep the Straub films in service should be sufficient guarantee that someday I will have a place in show business heaven. Does Jonathan think that I run a nonprofit operation? Does he know how much red ink all the Straub films are swimming in? Is he living in the same country as I am? Or is he confusing the U.S. with Bulgaria?

Over the years we have had our share of professional cranks in the critical community, but I’m afraid that J.R. takes the cake. I would appreciate it, if he wants to have any measure of respect from me, if he would, in the future, pick up the phone and call me and do his homework.

Daniel Talbot

New York

Jonathan Rosenbaum replies:

My apologies to Dan Talbot for misconstruing why Sembène’s films are unavailable on video, and my thanks for all his other clarifications; I’m especially delighted to hear the Celine and Julie will finally be out next year. I should have called him for more precise information rather than extrapolated from my previous impressions of New Yorker Films’ policies.

As both an exhibitor and a distributor, Talbot played a major role in defining as well as expanding our film culture in the 60s with his courageous, imaginative, and generous work, and we all still benefit from it in many ways. The film business, however, has changed a great deal over the past three decades, and New Yorker Films has changed with it. While I appreciate that Talbot runs a for-profit operation, it still bothers me that when the Film Center recently mounted a Kafka-on-film series they had to omit Straub-Huillet’s Class Relations because they couldn’t afford the $250 rental fee charged by New Yorker. Many film teachers I know — myself included — have frequently omitted New Yorker films from their courses because of similarly exorbitant fees. I also wonder why the videos released by New Yorker — though not those released by plenty of other capitalist video distributors have to be encoded with an anticopying signal so powerful that some of them can’t even be played normally without the light values shifting constantly. And of course I’m not confusing the U.S. with Bulgaria; I suspect it’s a bit harder to see Straub-Huillet films there than it is here. I just wish Talbot would consider what he means, exactly, by “keeping those films in service,” and how much it costs, in the final analysis, to get into “show business heaven.” [2011 postscript: Not longer after this exchange was published, I discovered that Sembene’s early shorts were commercially available on PAL video in the United Kingdom. And in more recent years, I’m happy to report, six of his eight features have become available in the U.S. on New Yorker DVDs — Black Girl, Mandabi, Xala, Camp de Thiaroye, Faat Kiné, and Moolaadé (although the first of these releases, lamentably, committed the error of processing Black Girl‘s brief color sequence in black and white) — without any objections, to the best of my knowledge, from either Sembène (who died in 2007) or his heirs. There is also a French box set of his films, regrettably unsubtitled in English, that purports to contain his complete works.]