From The Guardian, January 31, 2004. — J.R.

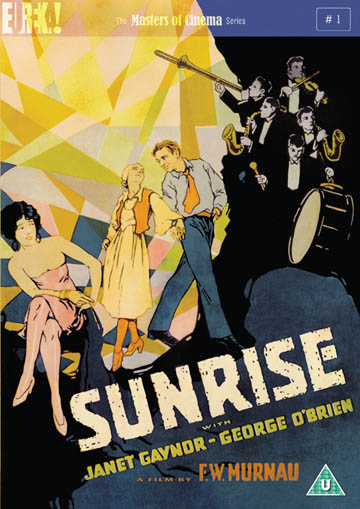

Some film industry bigwigs dream of owning a Rembrandt. In the 1920s, William Fox, head of Hollywood’s Fox studio, wanted a Murnau. A prestigious German director in his late 30s, F.W. Murnau already had 17 German features to his credit (only nine of which survive today). But this was an unprecedented case of a well-stocked studio giving carte blanche to a foreign director simply for the sake of prestige. Murnau took advantage of this opportunity by creating a universal fable that, as an opening intertitle put it, could take place anywhere and at any time: his 1927 masterpiece, Sunrise.

The standard line about the film is that it lost piles of money for Fox. Maybe it did. But film history often consists of writers dutifully copying the mistakes of their predecessors, and I’m afraid I have to plead guilty to having perpetuated this particular story myself. According to film curator David Pierce, “Sunrise was Fox’s third-highest-grossing film for 1928, surpassed only by Frank Borzage’s Seventh Heaven and John Ford’s Four Sons” — both films that were visibly influenced by Murnau. (The first, for starters, employed Gaynor, the second, some of Sunrise‘s sets.) Of course, it’s theoretically possible that the grosses didn’t make back the film’s cost, but I’d rather think that Fox’s investment paid off in one way or another. After all, it won no fewer than three Oscars — and we’re still looking at the film.

Like Citizen Kane, Sunrise is one of those movies that introduce viewers to the notion of film as art. It was Dorothy B Jones’s sensitive essay about Sunrise in a 1960 collection called Introduction to the Art of Movies that drove me to see it in the first place. Aside from her article and a couple of short reviews, the most enthusiastic writing I could find about the movie was in French, most of it in the pages of the magazine Cahiers du Cinéma. According to a poll of its critics in 1958, Murnau was the greatest of all film directors and Sunrise was his greatest film.

Part of what continues to make it great is its creation in a particular utopian moment in film history: the end of the silent era, when movies reached a certain pinnacle of visual expressiveness that was tied to a dream of universality, a belief that cinema could speak an international tongue. Properly speaking, Sunrise is less a silent picture than a pre-talkie, existing in a strange netherworld between sound and silence. It has a very beautiful and adroitly stylised soundtrack of music and sound effects, composed by Hugo Reisenfeld, that is an essential part of its magic.

The aesthetics of Sunrise have a lot to do with painting, music and literature, brought together in a remarkably interactive way that suggests another utopian dream: a definition of cinema as the meeting point for all the other arts. Subtitled A Song of Two Humans, the film has three movements, beginning and ending with slow tempos in a rural setting that are separated by an urban Scherzo. Apart from the happy ending, which functions like a coda, the movements might be described as melodramatic, comic and tragic, in that order — accompanied by a painterly control of light passing from night to day in the first movement, from day to night in the second and again from night to day in the third.

The characters don’t have names but generalised labels. The Man (George O’Brien), a simple farmer, is having a torrid affair with a vacationing City Woman (Margaret Livingston, one of the central characters in Peter Bogdanovich’s recent film about 1920s Hollywood, The Cat’s Meow). She signals to him, by whistling, to meet her for a night of lovemaking in the marshes. Wanting him to move with her to the city, she proposes that he drown his Wife (Janet Gaynor) in the nearby lake; but when he tries to carry out this plan the next day, en route to the city, he recoils in horror and succeeds only in terrifying his victim. Over a day and an evening in the city, the married couple gradually become reconciled and fall in love all over again. But when a storm breaks out on their way back across the lake, the Wife apparently drowns.

With a story this elemental, inflections are everything, and Murnau’s richly imaginative and nuanced direction synthesises performances, sets, camera movements and special effects (including many different kinds of superimposition) to spell them out. Early on, when the Man walks across the meadow to meet the City Woman in the marshes, the camera, in a startling effect, eerily takes on an independent intelligence: first following the Man, then moving alongside him and finally rushing ahead of him to arrive at the City Woman by a separate route, before he does. And her evocations of the city once they meet are sexually charged expressionist visions rendered through double exposures and camera gyrations, while the overlaps and distortions of the music convey the same cacophony. Even the intertitles are integrated graphically in the visual design: the City Woman’s line “Couldn’t she get drowned?” sinks and wavers like a body receding below a lake surface covered by mist — an effect complemented at the very end of the movie, when the watery, wavering title “Finis” stiffens from the heat of the rising sun.

“They say that I have a passion for ‘camera angles’,” Murnau wrote in 1928. “To me the camera represents the eye of a person, through whose mind one is watching the events on the screen. It must follow characters at times into difficult places, as it crashed through the reeds and pools in Sunrise at the heels of the Boy, rushing to keep his tryst with the Woman of the City. It must whirl and peep and move from place to place as swiftly as thought itself.”

Some actions are deliberately and musically protracted to create an ominous mood; when the Man slowly advances towards his Wife in the boat to throw her overboard, Murnau had 20lb of lead placed in O’Brien’s shoes to keep his movements sufficiently heavy and slurred. In the justly celebrated trolley ride taken by the couple into the city, the orchestration of O’Brien’s and Gaynor’s exquisite acting (depicting her fear and his remorse) with the shifting landscapes behind them suggests both a fusion of melody with harmony and a powerful modulation, passing from the minor key of the film’s first movement to the major key of its second.

The city itself — a gargantuan set built on Fox’s backlot, teeming with choreographed activity — is made to conform to a frightened rural couple’s perception of its size, noise, confusion and scale, and the Luna Park they visit in the evening is an even more delirious expressionist construction. Also striking is the embodiment of the couple’s enraptured state as they sail home across the lake, when a passing raft with silhouetted figures dancing around a bonfire captures their wild and exalted bliss, and the Wife ecstatically rocks her head back and forth in time to the music.

For all the dated and melodramatic aspects of Murnau’s eccentric stylisation, the erotic charge of the Man’s two relationships — a sexual object for the City Woman, a dominating figure to his Wife — remains startling today in its directness. In more ways than one, Sunrise triumphs as a masterwork of thought and emotion rendered in terms of visual music, where light and darkness sing in relation to countless polarities: day and night, fire and water, sky and earth, city and country, man and woman, thought and deed, good and evil, nature and culture.