From the Chicago Reader (March 29, 1996). — J.R.

The Decalogue

Directed by Krzysztof Kieslowski

Written by Kieslowski and Krzysztof Piesiewicz

With Henryk Baranowski, Krystyna Janda, Aleksander Bardini, Daniel Olbrychski, Maria Pakulnis, Adrianna Biedrzynska, Janusz Gajos, Miroslaw Baka, Krzysztof Globisz, Jan Tesarz, Grazyna Szapolowska, Olaf Lubaszenko, Anna Polony, Maria Koscialkowska, Teresa Marczewska, Ewa Blaszczyk, Piotr Machalica, Jerzy Stuhr, and Zbigniew Zamachowski.

Fargo

Directed by Joel Coen

Written by Ethan Coen and Joel Coen

With Frances McDormand, William H. Macy, Steve Buscemi, Peter Stormare, Kristin Rudrud, Harve Presnell, Steven Reevis, John Carroll Lynch, and Steve Park.

One way of judging the importance of filmmakers is by looking at the kind of talk they generate among their audiences. Since the recent death of the 54-year-old Krzysztof Kieslowski during open-heart surgery, one of the key points of speculation about him is whether he knew when he announced his retirement a couple of years ago that he had a heart condition. As evidence that he did, one could cite the fact that the “twin” Polish and French heroines of his The Double Life of Veronique (1991) suffer from heart conditions, and one ultimately dies from hers; as evidence that he didn’t, one could note that Kieslowski was a heavy smoker and continued to smoke after his announcement (though he may have been simply reckless). And prior to his last heart attack he’d begun work with his longtime collaborator, Krzysztof Piesiewicz, on a script for a new trilogy structured around the themes of heaven, hell, and purgatory — not necessarily in that order. A deeply controversial filmmaker on both sides of the Atlantic, Kieslowski can’t be deemed a greater or lesser figure on the basis of what he knew about his heart, but perhaps it isn’t a coincidence that his attitudes toward his characters are frequently ambiguous, the issues they raise never closed.

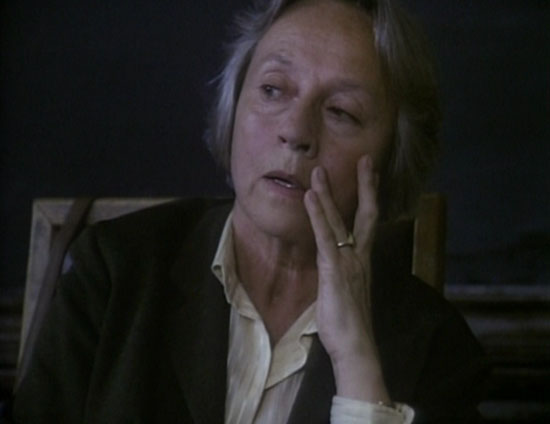

Kieslowski’s ten-part 1988 Polish miniseries, The Decalogue — a work (playing this week at Facets Multimedia) that can easily be seen piecemeal, because the films don’t depend on one another for their principal meanings — should be judged to some extent by the quality of the discussions it provokes about ethics. Each 50-odd-minute film recounts a story set in contemporary Warsaw in which a character breaks one of the Ten Commandments in some fashion, though Kieslowski is too cagey to identify overtly which commandment goes with which story or to explain other connections — such as why the Sixth Commandment [see photo above], “Thou shalt not commit adultery,” is represented by a story in which neither of the principal characters is married. His use of a different cinematographer on all but two of the ten films also makes each story a separate stylistic adventure, especially in terms of light and color. The greatest source of unity may be that nearly all the major characters live in the same housing project, so that major characters in one film are apt to reappear as minor characters in one or more others. (“It’s the most beautiful housing estate in Warsaw, which is why I chose it,” Kieslowski once said, typically adding, “it looks pretty awful, so you can imagine what the others are like.”) As another example of this kind of fascinating crossover — The Decalogue has several — the central ethical dilemma faced by a hospital consultant (Aleksander Bardini) in the second film is recounted as part of a university lecture in the eighth.

All of the films in The Decalogue are easy and pleasurable to follow as stories, yet part of the excitement they generate stems from discussions about their meaning after their dramatic impact registers. As Stanley Kubrick pointed out five years ago in his brief foreword to the published script of The Decalogue, Kieslowski and Piesiewicz “have the very rare ability to dramatize their ideas rather than just talk about them. By making their points through the dramatic action of the story they gain the added power of allowing the audience to discover what’s really going on rather than being told….You never see the ideas coming.” Interestingly, postscreening discussions tend to be exegetical without ever becoming religious; some critics’ patter to the contrary, Kieslowski belongs to the agnostic Bergman camp, not to the mystical Tarkovsky one.

The Decalogue harks back to a notion of conceptual art movie that reeks of the 60s — specifically, zeitgeist filmmakers like Antonioni, Godard, and occasionally Resnais — even though it’s exploring everyday urban life in the late 80s. The film can be comfortably situated in neither the Polish context of the Kieslowski features that precede it nor the Eurobabble New Age mysticism of the international coproductions that follow it (The Double Life of Veronique, Blue, White, and Red.) (However, it’s worth noting that there’s at least one intertextual detail that links the work of both periods: the imaginary Dutch classical composer Van der Brudenmajer, alluded to throughout the “Three Colors” trilogy as a kind of running gag, is first mentioned in the ninth film of The Decalogue.)

By way of contrast, a central point of postscreening discussions about Fargo, a Coen brothers crime story about a botched kidnapping set in wintertime Minnesota and North Dakota, is whether this story is based on fact, as it claims to be — discussions that invariably lead nowhere. “This is a true story,” states an extended title at the beginning, which goes on to explain that the events took place in 1987 (coincidentally, around the same time that The Decalogue was being scripted), that at the request of the survivors the names of the characters have been changed, but “out of respect for the dead” everything else in the film is true. This being a Coen brothers movie, one’s likely to scoff or smirk at such a claim, but even if one doesn’t the last thing on the end credits — “No similarity to actual persons living or dead is intended or should be inferred” — surely deserves a smirk of its own.

However, I don’t think anyone in the general audience who sees Fargo — and that includes me — cares in the slightest whether any of the events actually occurred, regardless of how one feels about the movie. The opening and closing titles are strictly pro forma, and the same could be said for the movie’s characters — though this is the Coen brothers in a hyperrealist mode, meaning that the characters are at least superficially more realistic than those in any previous Coen brothers feature.

The abrasive caricatures in the Coen brothers’ work, not to mention the low-angle Steadicam dollies they often favor, periodically remind me of Kubrick and his combinations of misanthropy and seamless technique — but the thematic differences are crucial. Virtually all of Kubrick’s features concentrate on elaborate, ingenious control systems that ultimately spin wildly out of control. (After the opening section in Full Metal Jacket, it’s the narrative itself that goes haywire, though most critics — with the rare exception of Bill Krohn in Cahiers du Cinéma — saw this as a failing rather than as a radical, meaningful artistic strategy.) In Fargo there’s no ingenious control system to dismantle; the kidnapping plot that sets everything else in motion is harebrained, and no part of it is carried out with any precision, so all that one can observe is an ugly, messy situation that becomes progressively uglier and messier — particularly since it’s juxtaposed with the unvarying forbearance of the pseudopopulist heroine, a cop assigned to clean up the mess.

One thing Kieslowski and the Coens have in common — apart from heavy-handedness at their worst moments — is that they are regionalists and historians, though many qualifiers have to be added to this description. Kieslowski never learned French fluently, a language spoken in all four of the films he made after The Decalogue — a failing that earned him the scorn of some French critics; and like Antonioni, Godard, and Resnais in their zeitgeist modes, he remained a historian exclusively of the present. The Coens, who hail from Minneapolis, can be considered regionalists prior to Fargo only if one considers television a regional culture — and I think in some ways one can; in Fargo they take on their home turf as well as their TV culture, and the results are singular. In most of their pictures TV culture counts for much more than geographical setting and historical period. It’s only in their pictures set in the present (Blood Simple and Raising Arizona) and in the near present (Fargo) that they qualify as historians worthy of the name; otherwise they’re basically mixing and playing with media clichés, paying scant attention to real places or actual periods.

Broadly speaking, both The Decalogue and Fargo have a lot to do with television, but Fargo represents an apotheosis of a peculiar posthumanist TV tradition that the Coen brothers have made their own — to the same degree that The Decalogue, though it was made for television, represents an apotheosis of a humanist tradition in movies that may be on the verge of disappearing. I realize this sounds fairly overblown, but I suspect that how one values either work has something to do with how one values human life.

To clarify my biases about TV, I should stress that I’m thinking less of TV content — the impetus behind Clinton’s much-debated V-chip proposal — than of some basic properties of the medium. Studies disagree about whether watching violence on television makes children more violent, but there seems to be something closer to a consensus that watching television of any kind tends to make children’s behavior more aggressive and antisocial. I would guess that this is partially true because remote-control buttons, channel dials, and on-off switches let us make other people appear and disappear, a power we can’t enjoy in the world outside television; by extension we have a solipsistic habit of thinking that people don’t fully exist if they’re not on-screen.

Combine this habit with certain stylistic practices associated with commercials and sitcoms and you have the only kind of reality available to characters in a Coen brothers movie; whether these characters are lovable or detestable, they’re lovable or detestable in a TV way — defined by a minimal set of traits that are endlessly reiterated and incapable of expansion or alteration, a fixed loop. By these standards Marge Gunderson (Frances McDormand), a cheerful, methodical pregnant police chief, and Jerry Lundegaard (William H. Macy) — a wormy car salesman from Minneapolis who’s in debt and hires two thugs (Steve Buscemi and Peter Stormare) to kidnap his wife (Kristin Rudrud) to get a ransom from her wealthy father (Harve Presnell) — have the predigested reality of TV personalities, but not the everyday reality of most of the characters in The Decalogue. (Though Kieslowski’s work does include one striking exception, the “silent witness,” a mysterious young man who briefly turns up in eight of the films — he can be seen warming his hands by a bonfire at the beginning of the first. This mythological figure points to the more pretentious side of Kieslowski, and I, for one, could have done without him.)

The lack of surprises in the story line of Fargo further suggests that style and attitude are just about everything for the Coens, and in some ways the plot details that are omitted — such as how Jerry ran up his debts in the first place and why Marge doesn’t hear about a double murder in Minneapolis that’s central to her investigation before she tracks down one of the killers — are more interesting than those that are included. By contrast, it’s almost impossible to describe the plots of most films in The Decalogue without giving away twists, which is why I’m mainly keeping mum about them.

I don’t mean to imply by any of this that the Coens are cynical and that Kieslowski isn’t. One thing that probably makes Kieslowski more controversial in Europe than in the U.S., and the Coens more controversial in the U.S. than in Europe, is that their commercial calculations are more easily perceived at home than elsewhere, without the window dressing of subtitles. Above all The Decalogue is a packaging idea, successfully designed to give Kieslowski an international reputation and made in part for export — which is why, by his own admission, Polish politics, queues in front of shops, and ration cards were all pointedly excluded and the all-purpose symbolic “silent witness” was slipped in as an afterthought.

Yet Kieslowski seemed anything but cynical when it came to television. As he put it in the book Kieslowski on Kieslowski: “I don’t think the television viewer is less intelligent than the cinema audience. The reason why television is the way it is, isn’t because the viewers are slow-witted but because editors think they are….This doesn’t apply so much to British television which isn’t as stupid as German, French or Polish television. British television is a little more predisposed to education, on the one hand, and, on the other, to presenting opinions and matters connected with culture…and this is done through their precise, broad, and exact documentary films and films about individuals. Whereas television in most countries — including America — is as idiotic as it is because the editors think people are idiots.”

That’s what the Coen brothers seem to think too; if one considers all the laughs found in Blood Simple, Raising Arizona, Miller’s Crossing, Barton Fink, The Hudsucker Proxy, and Fargo, there are very few that aren’t predicated on some version of the notion that people are idiots — the people on-screen, that is; those in the audience laughing at the idiots are hip aficionados, just like the Coens. In Fargo one way to gauge the degree of idiocy of the characters is by observing what they’re watching on TV. After the kidnappers have sex with bimbo prostitutes on twin beds in a roadhouse, all four of them are seen watching the Tonight Show together, which merits a sizable guffaw; then we cut to Marge beside her sleeping husband in their bedroom watching a nature documentary about insects, which produces only a titter. (If Marge were watching the Tonight Show and the kidnappers and prostitutes were watching the nature documentary, the scale of the relative derision would doubtless be reversed.) Later on the sullen, silent kidnapper (Peter Stormare) is seen watching a daytime soap on a set with poor reception while he distractedly scarfs down junk food, which is considered more worthy of our interest than the kidnapped woman who lies dead in a corner of the same room; precisely when and how she died is made to seem a trivial matter — a passing detail, lost (as it were) between commercial breaks. Granted, this emphasis may be a commentary on the callousness of the kidnappers; but isn’t it also a commentary on the callousness of the Coens and their audience?

This may seem to mark the Coens as smart-alecky opportunists, but if one looks more closely at their filmmaking practice as opposed to their gags and put-ons, they’re clearly interested in being artists, not simply in making a killing at the box office. The complex web of paranoid misapprehensions that form the noirish plot of Blood Simple should be perceived as an artistic statement about the period we’re living in — as the opening narration comparing Texans to Russian communists suggests — and not merely as a set of heartless genre mechanisms, though it’s also that.

As a further indication of this, let me cite what I regard as the key scene in Fargo — a disturbing interlude that strikes many others as wrong or dubious because it has nothing to do with the story proper. Late one night Marge gets a phone call from a guy she knew in high school, Mike Yanagita (Steve Park), who’s now based in the Twin Cities; it’s strongly hinted that they used to be a couple. (Marge is now married to a wildlife painter named Norm who works mainly at home.) Mike had seen Marge on TV in connection with her murder investigation, and the next day they wind up meeting in the bar of her hotel. Frantically trying to reestablish some intimacy with her by sitting next to her in their booth (she firmly but politely asks him to move back to the other side), Mike tells her he was married to an acquaintance of hers named Linda, who died of leukemia; he adds that he’s been working as an engineer, then breaks down in convulsive sobs and speaks forlornly about his loneliness. The next morning, chatting on the phone to another old friend, Marge discovers Mike was never married to Linda (who’s still very much alive), has “psychiatric problems,” and lives with his parents — and this is the last we hear of him.

In terms of plot this episode is awkwardly extraneous, but in terms of theme — a lonely individual lying compulsively, trying without success to hide his desperation — it registers as central. Even the fact that Mike’s ethnic background is Japanese while nearly everyone else, including Marge, is Swedish-American may be relevant; it seems that Swedish-Americans have nailed-down styles for articulating their emotional repression in social situations — grotesquely unfeeling in Jerry Lundegaard’s case, especially when he’s speaking to his wife or son, affable and easygoing in Marge’s — and Mike doesn’t. In any case, the sheer unresolved embarrassment of this scene has nothing to do with the movie “working” in commercial terms and everything to do with the Coens trying to give it some artistic coherence. Yet it’s still only half a gesture, because they’re seemingly unequipped to make Mike anything more than a sitcom character — a two-dimensional geek whose first words to Marge after greeting her are a reference to her hotel: “You know it’s a Radisson, so you know it’s pretty good.”

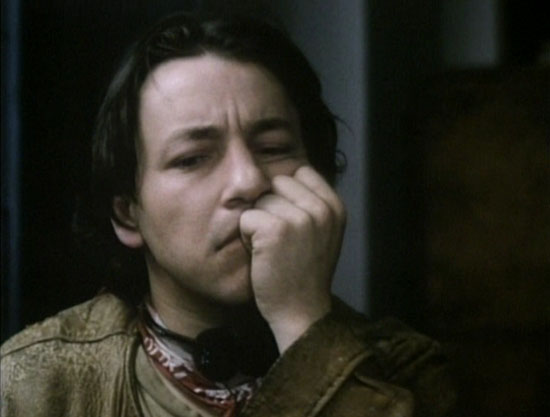

Nobody could ever accuse Kieslowski of this kind of misanthropic, and, I would argue, TV-derived shorthand, no matter how sarcastic he gets. The most odious character I can think of in The Decalogue is a young, virtually motiveless killer (Miroslaw Baka) from the countryside who figures centrally in the fifth film (“Thou shalt not kill”) — known as A Short Film About Killing in its expanded 85-minute version — but at no point does Kieslowski present him simply with disdain or a curt dismissal. Indeed, this character’s eventual public execution is made to seem just as horrific as his own gratuitous murder of a cabdriver; both events are shown in real time, implicating the viewer in each process. We never learn very much about him, and no effort is made to make his victim likable or charismatic, but they’re both worthier human beings than anyone the Coens have filmed — even worthier than Marge, their seeming favorite — because they have a wider, more varied, and less predictable pool of human traits. No one in Kieslowski’s world is ever bigger than life; in the Coens’ world you virtually have to be to get their form of validation and recognition. (The Native American auto mechanic and ex-convict is emblematic of this knee-jerk hyperbole; when he explodes in a violent rage at one point he might as well be the mythical biker and bounty hunter in Raising Arizona, a mere assembly of pasteboard movie conventions.)

“Rich fellas come up an’ they die,” Ma Joad says at the end of John Ford’s The Grapes of Wrath, “an’ their kids ain’t no good, an’ they die out. But we keep a-comin’. We’re the people that live. Can’t nobody lick us. We’ll go on forever, pa. We’re the people.” Perversely, I was reminded of this hokey speech during the last scene of Fargo, which features Marge and Norm (John Carroll Lynch) conversing in bed — the only characters toward whom the Coens can express any warmth. But if the Joads in 1940 stood for some sort of populist triumph over social injustice and adversity, the salt-of-the-earth Gundersons become expendable as soon as they serve their prescribed function — which is to validate our amused tolerance for good-hearted folks with funny accents and down-home truths surviving in an absurd universe. But the world they inhabit is devoid of other meaning, too grim to make their survival count for much more than first place in the Coens’ hit parade of favorite hicks.

The regional flavor of Kieslowski’s Warsaw in The Decalogue is only slightly less acrid, but its sourness is ultimately made to seem incidental rather than central to the ten tales being told. The fact that each film in the series lasts less than an hour might have something to do with this. (A Short Film About Killing makes room for more cruelty and violence, including a cat’s body swinging from a rope and the killer crushing the cabdriver’s dentures, but I’m not persuaded it has anything more to say about breaking the Fifth Commandment.)

One thing that’s potentially exciting about movies that last about an hour is how much can be done within that format. Admittedly, a lot of Hollywood B-films of the 40s and 50s with comparable running times are strictly from hunger, but if one turns to masterpieces and near masterpieces, ranging from the Val Lewton horror classics, William Castle’s When Strangers Marry, and Walt Disney’s Dumbo and The Three Caballeros to Ousmane Sembene’s Black Girl, Luis Buñuel’s Simon of the Desert, and Christopher Munch’s The Hours and Times — or even to just well-crafted jobs like most of the quickie thrillers done in the “Whistler” series in the 40s — it’s surprising how rich and satisfying many of them are. (By comparison it’s amazing how padded most current features are. If many short features, such as those from the 30s, tend to speed up narrative events unnaturally, the average 100-minute or two-hour feature of today tends to slow them down just as mechanically.)

Charting moral ambiguities among characters who are never as fixed or as finite as we initially suppose, the ten films of The Decalogue are brave enough to yield questions that demand further thought rather than elicit our self-applause for recognizing our superiority to — or even our affection for — the characters on-screen. The finely sculpted scripts of these films become suggestions about how we might think about these people, not directives about how we should judge them. This contemplative style doesn’t prevent any of these films from being entertaining; some of Kieslowski’s jokes can be downright raucous, like the Polish punk-rock invitation to break all the commandments that launches the tenth film, and I can’t say that any of the films in The Decalogue ever bored me. But they’re usually entertaining in a quiet way, without the stylistic grandstanding the Coens seem to require to function at all. As dark and sardonic as The Decalogue and Fargo are in their alternating sweetness and sourness — above all in their comic and despairing depictions of the multiple, complex secrets people keep from one another and sometimes from themselves as they try to place their lives in order — only The Decalogue sends me out of the theater with some measure of hope.