As far as I know, this is the only long review of mine for the Chicago Reader that isn’t on the Reader‘s web site, and consequently it wasn’t on this site, either, until I retyped it for inclusion here. It appeared in their May 17, 1999 issue. It’s also one of the pieces selected and translated into Farsi by Saeed Khamoush for the unauthorized collection of some of my Reader pieces that was published in Iran back in 2001. — J.R.

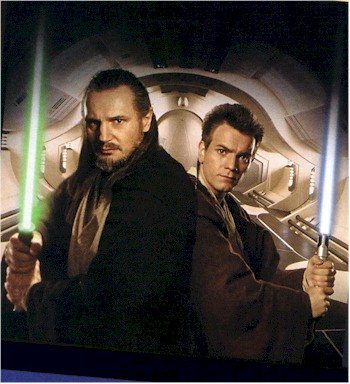

STAR WARS: EPISODE 1—THE

PHANTOM MENACE

**

Directed and written by George Lucas

With Liam Neeson, Ewan McGregor,

Natalie Portman, Jake Lloyd, Ian McDiarmid,

Pernilia August, Ahmed Best, Frank Oz,

Samuel L. Jackson, and Ray Park.

TREKKIES

0

Directed by Roger Nygard

The big question about the Star War series, and The Phantom Menace in particular, isn’t how much you like it but whether you love it. The issue is above all generational, and only secondarily a matter of aesthetic or ideological choices.

If you’re male and were born around 1989, the chances of you loving The Phantom Menace seem fairly high. If you’re male or female and were born around 1967, the chances of you loving it are probably almost as high. For better and for worse, seeing The Phantom Menace is like revisiting your youth, the time when you first saw Star Wars or either of its sequels. And if you’re female and born at some other time, chances are you’ll be asked to sit back, admire Natalie Portman’s painted lower lip, and go with the flow. To refuse such an invitation is to run the risk of being considered historically challenged — especially given that the American media are making the movie out to be at least as important as NATO’s war against Yugoslavia.

Will the Force leave us alone? Not bloody likely. But even as the inevitable backlash starts, the odds of George Lucas not hitting the jackpot again seem minuscule. At the press screening I attended, viewers were asked to rat on any of their colleagues who might be armed with a camcorder. I spotted a cellular phone, but apparently the danger of someone relaying the sound track to a friend outside was deemed less serious. And the possibility that any of us might not like the movie enough to want to duplicate it doesn’t seem to have been considered. In fact, the applause at the end was fairly desultory, but since I’ve always regarded test marketing (official or unofficial) as a form of voodoo science, I wouldn’t dream of making any predictions about the film’s success from such a response. Even if the movie were terrible -– and it isn’t -– it would clearly hit the top of the charts, if for no other reason than that people would feel they had to confirm their worst suspicions.

Like Lucas, I was in my early 30s when the first Star Wars appeared, and even if it reminded me of stuff I enjoyed as a kid, it wasn’t the kind of stuff I was then looking for. The closest Lucas has ever come to giving me a primal experience was THX 1138 [see photos directly above] -– his first feature, an SF art movie coscripted by Walter Murch, which I saw twice in 1971, six years before Star Wars. If memory serves, I was stoned out of my gourd both times and what made the experience primal was its high-modernist look and feel: it’s very attractively framed, and it’s composed of equal parts Jean-Luc Godard’s Alphaville, Michelangelo Antonioni’s Red Desert, and Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey. Browsing recently through a letterboxed copy on video, I was intrigued to discover how much of the décor, costumes, and overall visual design of the future Star Wars cycle was evident in this dystopian poem of alienation, even if its claustrophobic mood was light years away from the euphoria of the series that was to come.

Lucas’s flair for creating provocative compositions and striking settings was already fully in place, though he hadn’t yet learned the provocative strategy of leaving them on-screen only long enough to tease the imagination -– a strategy he would use to great effect in Star Wars and The Phantom Menace. This principle of economy is fully compatible with the decision to open The Phantom Menace at only four theaters in Manhattan; leaving the audience wanting more is a venerable showbiz staple.

The first Lucas epiphany for viewers slightly younger than I might have been hearing “Rock Around the Clock” over the credits of American Graffiti in 1973, an effect that was diminished for me because I’d already been jolted by hearing the song over the credits of Blackboard Jungle back in 1955. Lucas’s second feature was considerably more cheerful than his first, though it recapitulated the theme of trying to escape from a closed system -– a totalitarian future in the first case, an adolescent way of life in the second; there was still a fragrant sense of mystery about the world outside the confining labyrinth, another example of Lucas’s clever withholding strategy. Who could have guessed that abolishing any outside world in his third feature would make Lucas a billionaire? And who would have guessed that its inside world would embrace all the boyhood fantasies he picked up at 50s Saturday matinees?

“What I was going for was a kind of modern look,” Lucas told Ann Thompson in Premiere’s May issue, referring to Star Wars. “I guess I succeeded, because it hit a chord with people.” Yet in contrast to the unabashed modernism of THX 1138 and the concealed modernism of the much more profitable American Graffiti, Star Wars was postmodern with a vengeance -– a giddy recycling of old serials, westerns, and World War II epics that emphasized the idea of familiarity over any sense of the unknown. “An hour into it, children say that they’re ready to see it all over again, Pauline Kael wrote in her two-paragraph review in 1977; “That’s because it’s an assemblage of spare parts….Star Wars may be the only movie in which the first time around the surprises are reassuring.”

Is The Phantom Menace reassuring, comfortable, satisfying? Yes and no. People who want a product commercial that offers an elaborate context for past, present, and future purchases will probably find it teeming with satisfactions. Kids in their 30s hoping to recapture something of their initial Star Wars high may find the restimulation of ancient thrills undercut by all the advance hype. Though I’ve been bored senseless by the Star Wars phenomenon for over two decades, I found The Phantom Menace something of a pleasant surprise –- not because it’s better than chapters four or five (I’ve never seen Return of the Jedi), but because it’s clunky and old-fashioned in spite of (or maybe even because of) all the digital effects, because it’s more about the past than the future, and because it’s consequently more human in ways I can appreciate.

***

If you love or are bored by something, evaluative criticism is a secondary issue at best, irrelevant at worst. A couple of years back I angered some readers of this paper by hypothesizing that the uncommon glee with which some Americans drop bombs on people they don’t know anything about and can’t see might be traced in part to the euphoria of watching the bloodless, corpseless annihilations in some of the interstellar battles in the Star Wars movies, a euphoria that seems safe because we all know the difference between who’s good and who’s evil — as long as we have the right scorecard.

I find this boys’ fantasy of empowerment boring, but I’m just as bored by the relatively progressive and nonviolent underpinnings of Star Trek (the TV and movie versions) even if its social consequences are more beneficial. Maybe it’s because I’m the wrong age or because I don’t watch enough TV. Certainly I’m fascinated by what unquestioning love for cultural objects means, so I was looking forward to a documentary about Star Trek cultists, hoping to learn things I didn’t already know about why they love the show so much and what the consequences of that love were. But Roger Nygard’s Trekkies was a slap in the face — a geek festival that mainly invites us to hoot at a bunch of alleged crazies, ranging from a dentist who decorates his office and assistants with Star Trek paraphernalia to various collectors and fanatics who attend Star Trek conventions. The opposite of a sympathetic or insightful look into a fringe phenomenon — unlike Jennie Livingston’s 1990 Paris Is Burning, which concerns voguing and Harlem drag balls and is playing this Sunday at the Music Box — Nygard’s documentary sinks early on into the derisive mode of the worst TV talk shows and then stays there.

Nygard could have gone after the fanatics who hoard Disney or Star Wars collectibles with the same jaundiced pseudocompassion. I suspect the only reason he didn’t is that mainstream audiences might have been outraged. When it comes to freak spotting, Trekkies are apparently fair game. The absence of any real curiosity about the show or its fans or the fascinating cottage industries it has spawned — including laptop-published porn fiction for women that uses the Star Trek characters — is so overwhelming that it gradually victimizes the show’s cast, creators, and fans, making them all part of the same insultingly one-dimensional discourse. Eccentricity as spectacle becomes the only bill of fare. Like much of Star Wars, this too can be traced back to the 50s; Art Linkletter’s People are Funny is one probable locus classicus.

***

On one level, Star Wars was like camp with all the comic implications removed, but it least it replaced those implications with a sprightly and irreverent sense of humor -– a virtue imported more or less intact from American Graffiti. Some of the humor lay in Han Solo’s wisecracks, but most of it had to do with the banter and interactions among several characters. Yet after the surprise ending of The Empire Strikes Back, which reveals the identity of Darth Vader, Lucas started to take himself much more seriously -– no doubt prompted in part by the claims of academics and newsmagazines that he was carrying on the great tradition of Homer, the Old Testament, Virgil, the Koran, and Joseph Campbell. The light entertainment that had decisively replaced the art-movie deepthink of THX 1138 began to be informed by a “dark side” that honored the pseudoreligious fervor that had greeted the series.

Nearly two decades later, nearly all of the smirking comedy has been drained away. Not even a jive master like Samuel L. Jackson cast as a member of the Jedi council in The Phantom Menace, is allowed to make us smile — which is about like casting Esther Williams in a seaside musical and not giving her a chance to swim. The stilted heaviness and solemnity even overtaking an actor as able as Liam Neeson, here playing the key role of Jedi master Qui-Gon Jinn as if he were a poker-faced Jock Mahoney plowing his way through a Republic western. In fact, just about the only source of sustained comedy is an overgrown lizard of indeterminate gender named Jar Jar Binks, whose Jamaican-inflected voice is supplied by Ahmed Best -– “a kind of extraterrestrial Stepin Fetchit,” as Newsweek’s David Ansen puts it, whose main function appears to be periodically telling the audience when it’s OK to laugh. Admittedly Smiley Burnette and Gabby Hayes performed the same duty for Gene Autry and Roy Rogers. But in better westerns such as Rio Bravo someone like Walter Brennan could turn everyone in his vicinity, including John Wayne, into a complementary figure of fun. Jar Jar Binks gets exclusive buffoonery rights, and Qui-Gon Jinn, despite his incongruous name, seldom gets to crack so much as a smile.

It’s the sort of silliness that only a filmmaker who gets to control his vision could create — and it distinguishes The Phantom Menace from most other summer blockbusters which reek of mixed messages sent out by nervous test marketers and dimwitted cost accountants. Which isn’t to say that The Phantom Menace isn’t often dimwitted, but it’s hard to imagine that a committee would have agreed to a trick-or-treat villain like Darth Maul (Ron Park, who’s made up like a red devil sprouting numerous horns like pimples — an emblem of amateur theatricals) or to a future Darth Vader as bland as Jake Lloyd’s Anakin Skywalker. A bank might well have given us an Asian-empress heroine as stilted as Portman’s Queen Amidala or a young Obi-Wan Kenobi as boring as Ewan McGregor — though neither actor can be faulted for that, any more than Neeson or Lloyd can be blamed for their vacancies — but a bank probably wouldn’t have deprived these characters of all humor. Even Frank Oz’s Yoda has to belie his comic gnome appearance by spouting solemn directives to Obi-Wan Kenobi that sound like bad translations of a United Nations assembly: “Qui-Gon’s defiance I sense in you. Need that, you do not. Agree, the council does. Your apprentice, young Skywalker will be.”

I guess it’s hard to think about laughs when you’re pondering origin myths: Shmi Skywalker (Pernilla August) replies to Qui-Gon’s query about who Anakin’s father was with a strong hint of immaculate conception: “There was no father that I no of….I carried him, gave him birth….I can’t explain what happened.” In Lucas’s New Testament, which precedes rather than follows his Old Testament – one more example of irrational postmodernist license – only Lucas himself can qualify as God the Father, while the banks and cost accountants and academics and newsmagazines serve as apostles spreading the holy word.

Maybe I’m being perverse, but what I like about The Phantom Menace is its awkward sincerity and unabashed pomposity, the way Lucas has finally been engulfed by the charming awfulness of his Saturday-matinee models. Some of this is clearly deliberate: as a title, The Phantom Menace sounds exactly like a chapter heading some Republic serial, and all the old-fashioned wipes between sequences come straight out of that tradition. Some of it is merely unfortunate: it seems likely that Lucas got so hung up on his digital effects, which apparently fill about 95 percent of the screen, that he left his actors stranded –- effectively eliminating most forms of nondigital effort in the process, including his own. Reportedly he even used digital techniques to tweak the performances, matching a facial expression from one take with a gesture from another; the result of this high-tech ingenuity is that all of his human actors are turned into blocks of wood — the same sort of thing that cramped budgets and lousy dialogue did in low-budget programmers of a half century ago.

It reminds me of a gourmet cook friend of mine who one evening expended as much energy reproducing McDonald’s cheeseburgers, fries, and chocolate shakes as she previously devoted to producing veal calvados. Since the beginning of the Star Wars cycle, Lucas seems to have made it part of his postmodernist project to vaporize existential identity as well as the history and geography that helped form it. What he hasn’t done before is prove beyond a shadow of a doubt that all the digital magic in the cosmos is less helpful than a set of crayons -– at least if you’re naïve enough to expect technology to take the place of imagination.

What Lucas has instead of creative vision is a ravenous memory -– he’s as ready to pillage the globe and history as his hero Indiana Jones -– and a talent for mixing and matching his plunder in a way that his digital effects can neither improve nor dignify. What emerges is triple-distilled grade-Z formula. In other words, he’s a hack, and to some extent he seems to know it. He even has the honesty to acknowledge that his amassed treasures are as old as the hills; one of the endearing charms of his neomedieval weaponry is how literally soiled and shopworn most of it is, and the best thing about Anakin’s race in his homemade “Podracer” — the closest thing in the movie to a set piece -– is that it evokes Ron Howard’s speeding in Eat My Dust (1976).

As a storyteller, Lucas is somewhat stymied this time around by having to fill in the prologue of a plot that some spectators probably already know as well as the story of their own lives. Most of us can’t take in The Phantom Menace as innocently as we took in Star Wars, because we know a good many things about the characters that they don’t yet know themselves. This may invest everything that happens with a certain amount of contextual significance, but the storytelling still has less of a sense of urgency than it had in Star Wars. If everything’s preordained — the movie was even storyboarded and scripted simultaneously — than the most that special effects can do is provide icing for the cake, occasionally smothering the characters in the process.

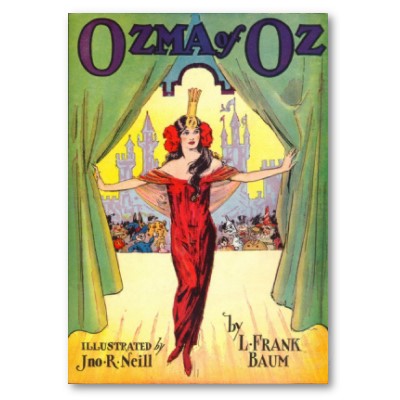

“A long time ago, in a galaxy far, far away…” Past, present, or future? Part of the accomplishment of the Star Wars cycle as a whole — a closed system, with even more interactive parts than the universes the heroes of THX 1138 and American Graffiti are bent on escaping — is to make that distinction irrelevant. Yet there’s still something comforting about the fact that The Phantom Menace is located only in the past — not just the past in relation to Episode IV, but the past that preceded digital technology, Lucas’s boyhood in a movie house or in front of a TV screen. Coruscant, the capital of the galaxy -– an eye-filling city that spreads across an entire planet –- is the “future” only in the way that the 1926 Metropolis is. The underwater city of Otoh Gunga could probably be traced back even further to John R. Neill’s illustrations in one of the Oz books, and every other piece of otherworldliness has a similar cozy familiarity. Various planets recycle the stereotypical settings, costumes, hair styles, and accents of Renaissance Venice, Africa, India, China, and the Middle East.

As far back as Louis Feuillade’s 1918 Tih Minh, imperialist and colonialist fantasies have been at the root of a good many serials, and, as in the Indiana Jones movies, Lucas merely brings those fantasies into the present, using the pedigree of the past to preserve and extend their innocence. Yet extending a particular past into the future is a way of guaranteeing the continuation of a profitable franchise. Walt Disney, a master of recycling his own products into infinity, covered over this fact by implying that his art was timeless. Lucas one-ups him by postulating that historical time begins and ends when his features and their revised editions get released; everything else, us included, is just the boring cosmos, waiting to be fleeced and plundered.