From the Chicago Reader (September 29, 1989). — J.R.

REMBRANDT LAUGHING

Directed and written by Jon Jost

With Jon A. English, Barbara Hammes, Jim Nisbet, Nathaniel Dorsky, Janet McKinley, Kate Dezina, and Jerry Barrish.

“The essence of Jean-Luc Godard’s La femme mariée,” John Bragin wrote in the mid-60s, “is the transmutation of the dramatic into the graphic.” While this formula doesn’t account for everything in Rembrandt Laughing, Jon Jost’s ninth feature, I think it provides a helpful clue to the overall direction taken by this masterful, elliptical account of a little over a year in the lives of a few friends in San Francisco.

For all his mastery and originality as a maverick independent, Jost has often alienated audiences with the harshness of his themes and the apparent distance from which he views his subjects and his characters. A 60s radical who spent over two years in federal prison for draft resistance, he has lived without a fixed address for most of his 26-year career as a filmmaker, and the alienation as well as the clarity stemming from his wanderlust has seeped into many of his fiction features. These have often centered on isolated individuals: a private detective in Angel City (1977), a drifter out of work in Last Chants for a Slow Dance (1977) [see two images below], a drug dealer in Chameleon (1978), a Vietnam vet in Bell Diamond (1987). (Even the two people who form the focus of the 1983 Slow Moves register more as lonely individuals than as a couple.)

Rembrandt Laughing, however, was made during probably the longest stationary period in Jost’s adult life, when he was living in San Francisco, and the difference in the film’s overall ambience is striking. (It was shot, fairly casually and intermittently, over the first two months of 1988, usually an hour or two at a time.) For once all of the characters are physically and spiritually grounded in a specific community and milieu, which means that the silences that exist between them are more often shared moments than gaping disjunctures or tortured absences in communication. In many respects it was made collectively with Jost’s friends — one of the lead actors (Jon A. English) composed the music, another (Nathaniel Dorsky) contributed a small section of footage, and most of the plot and (largely improvised) dialogue were worked out with the cast. It is nonetheless very much a Jost film, but with a warmth, philosophical depth, and overall sense of relaxation that are relatively new to his work.

Although the first and last scenes in Rembrandt Laughing are symmetrically structured and juxtaposed –both depict early morning visits of Martin (English) to Claire (Barbara Hammes), a woman he used to live with — there’s a random drift to many of the intervening sequences; they tend to focus more on everyday activities of various characters than on dramatic events. A few significant incidents do occur in these sequences — Martin’s friend Daniel (Dorsky), who is also a former lover of Claire’s, asks Martin to be the executor of his will; another character suddenly breaks into tears while looking at the San Francisco Bay with Claire, because her husband left her — but most of the time the characters are simply working or spending time together: telling stories, serving and eating food, sharing memories.

It is also worth pointing out that insofar as Rembrandt Laughing has a story, it is not always an easy one to follow, and if I give away much of the plot here, I don’t think that I’ll be spoiling the experience the film has to offer, which has more to do with the telling of the story than with any conventional narrative suspense. (I should give fair warning, however, that my synopsis will include a couple of delayed revelations in the story line, so some readers may prefer to skip what follows until after they’ve seen the film.) Martin’s first visit to Claire is occasioned by the fifth anniversary of their breakup, which he still regrets. He presents her with a photocopy of a Rembrandt etching, a self-portrait that shows the artist uncharacteristically laughing (which is subsequently used in the film to mark divisions between days). The two characters are mainly isolated from one another in separate shots — Claire still in bed or in the bathroom, Martin fixing her breakfast in the kitchen — and there’s a certain pathos in the way that Martin keeps hoping she’ll guess the reason for his surprise visit. The disjointedness of their responses to one another recalls earlier Jost films, but Claire gives Martin an affectionate hug before he leaves, and the scene concludes with a feeling of tenderness that somewhat mollifies Martin’s petulance about Claire not remembering their relationship as fondly as he does.

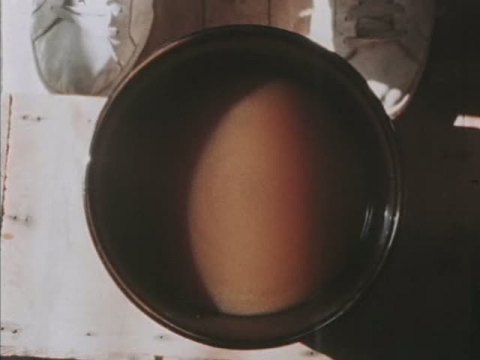

Later we see Claire and Martin at their jobs — Claire at an architect’s office, Martin doing woodwork at a picture framer’s — followed by another long scene when Martin visits Daniel, an old friend who collects sand from various countries around the world and keeps it in bottles, the scene in which Martin agrees to be the executor of Daniel’s will. (It’s only much later, in the final scene, that the film obliquely reveals that Daniel also used to live with Claire.) It is here that the film’s transmutation of the dramatic into the graphic first becomes fully apparent: the scene opens with an extreme close-up of miso soup being stirred while the two friends chat offscreen; somewhat later there’s a comparable close-up of some pebbles in a dish, and still later the camera focuses on some sand from Crete that Martin has brought for Daniel. (It’s worth noting that none of the extreme, extended close-ups of objects here and elsewhere in the film are static shots: the grains of sand, for instance, are lightly stirred by air currents.) The close-up of the pebbles is overlaid and eventually overtaken by rapidly dancing flashes of light (the footage contributed by Dorsky) that create a ravishingly beautiful kind of abstract scherzo over the easygoing offscreen conversation, which is accompanied by a strange rattling sound that seems connected with the pebbles (thematically if not in terms of the story). In contrast with the intensity of these three extended close-ups, Martin and Daniel are shown rather obliquely, and rarely within the same frame. The overall effect of this unorthodox sequence is to elevate the cosmic subtext of the conversation — the sense of infinity and mortality that hovers around the edges of the talk before Daniel brings up the matter of his will — so that it proceeds simultaneously with the more mundane everyday chitchat.

A week later we see Claire at work again, and Martin trying out for a job as an “explainer” to kids on tours at a San Francisco science museum called the Exploratorium. After running through his carefully prepared spiel, which ends with the line “I can explain everything,” Martin expresses concern to his potential employer about the implied hubris of that claim. The next day Martin prepares to compose some music on his synthesizer; he listens to Beethoven’s 15th Quartet in A Minor on earphones — a piece that is often heard again, becoming a motif rather like the Rembrandt etching and lending a sense of gravity to other events.

The next evening we see Martin talking to a bail bondsman (Jerry Barrish) about Daniel, who was arrested for possessing some grass and who turns out to have run up a $3,000 debt in unpaid parking tickets. This is the least successful scene in the picture, made especially unfortunate by the melodramatic appearance of two very unconvincing fake-Hollywood gangsters who wind up shooting the bondsman for a purely gratuitous reason. Just as the earlier sequences can be partially traced to some of the best work of Godard (the bowl of miso soup, for instance, springs directly from a similarly framed cup of black coffee in 2 or 3 Things I Know About Her), this sequence seems derived from the absurdist bursts of violence in some of Godard’s lazier work — with the difference that Godard at least knows the Hollywood crime movies that he’s spoofing, while Jost, it seems, can only grope after an imitation of a spoof. This sequence ends more agreeably with a 360-degree tracking shot around a sushi bar where Claire is eating with a new boyfriend, Jim (Jim Nisbet); Jost himself can be glimpsed sitting at the bar, and since he credits himself with photographing the entire film, one can only wonder what technical stunt was needed to pull this remarkable shot off.

The film fully regains its stride in the two closing sequences. The first of these is set a month later, and shows virtually all of the characters in various everyday activities; the overall ambience is relaxed and lyrical, recalling some of the interludes in Alain Resnais’ Muriel. Claire is in bed with Jim, Martin is watering his lawn, the bail bondsman (surprisingly still alive) gazes at the ocean, and Daniel is ice-skating — the latter occasioning another bit of virtuoso camera work.

In the final sequence, set a year later, Martin again appears at Claire’s apartment, this time carrying a heavy box. It emerges that Daniel has died and left his sand collection to Claire, and Martin is delivering it; Jim is still around, and this time it is he who fixes breakfast. Here again, the leisurely life-style of the characters is depicted at some length, although by now the characters have grown in density (English’s performance in particular has become increasingly convincing and lifelike over the course of the film). Jim reads the paper while Claire and Martin arrange the bottles of sand on her windowsill. At one point there’s another extended extreme close-up: this time it’s of what appears to be unusually dark sand. Later in the scene we discover that these are Daniel’s ashes, which he has bequeathed to Claire so that he can “keep on living with her,” as he explains in an accompanying letter. Claire doesn’t know whether to laugh or cry about this, and winds up doing something in between; Martin embraces her, comforting her in much the same way that she comforted him toward the end of the first sequence.

The above synopsis is far from complete; it omits, for example, that on various occasions different sorts of printed texts crawl across the screen, at odd moments and usually at odd angles. More important, it omits the very pleasurable opening sequence, before the credits, of Martin bicycling over to Claire’s — the whirring sound of the pedals and the oblique images of a foot, a turning wheel, moving pavement, and occasional shadows. They add up to a sensual blend that is every bit as exciting as Daniel’s ice-skating — not to mention the extended close-ups on various textures, including a beautiful shot of the rippling water of the San Francisco Bay. The elemental power of these privileged, electric moments in the film are in a sense what the whole story is “about,” to the same degree that both the image of Rembrandt–the painter of gloom–laughing and the sound of Beethoven’s 15th Quartet (identified by the composer on the manuscript as a “song of thanksgiving to the Deity on recovery from an illness , written in the Lydian mode”) are variations of the same basic feelings and ideas.

What may seem initially off-putting about the film is the degree to which portions of the story appear to be self-consciously “thought up” rather than discovered. As a storyteller, Jost has often shown a certain awkwardness in ordering events and controlling exposition — in striking contrast to his consummate command and skills as a cinematographer and sound recorder. But as Rembrandt Laughing suggests, the usual motives and satisfactions of story telling don’t interest him very much; he uses plot, well or badly, as a vehicle for arriving at something else — in this case the poetry and textures of everyday life. Implicit in the film’s moving final synthesis, and much closer to metaphor and poetry than to story and prose, is the realization that water, sand, ashes, pebbles, people, bicycling, ice-skating, and even fixing breakfast are much closer to being the same things than we ordinarily choose to suppose. I realize that this concept, as it’s baldly and awkwardly expressed here, may not make too much sense as prose; but go and see what Jost does with it cinematographically in Rembrandt Laughing, and you’ll get a much better idea of what I mean.