This was written for and published in Stop Smiling no. 34, a special jazz issue, dated February 2008. –J.R.

Keith Jarrett, Cross-Referencer

by Jonathan Rosenbaum

Jazz musicians who like to cross-reference the history of their art rather than simply steal licks from their role models are probably even more plentiful than film directors who do “homages” to favorite sequences and directors. The musicians also generally do a better job of mixing their own style with that of their models than Hollywood directors do when they strive to reproduce particular shots. Closer to Jean-Luc Godard or Alain Resnais than to, say, Peter Bogdanovich or Brian De Palma, they invariably bring something of their own to the table, transforming our sense of the original in the process. Every time Dave Brubeck chooses to shift to stride piano, he’s saying something sweet about his predecessors, and whenever Charles Mingus gave us patches of Jelly Roll Morton, Duke Ellington, Lester Young, or Charlie Parker in one of his multifaceted compositions, he was doing a more elaborate version of the same thing.

Some jazz pianists — including a few of the most distinctive ones, like McCoy Tyner and Keith Jarrett — even go so far as to put together entire albums composed of “tributes” to some of their colleagues. The less interesting way of doing this is simply to pick tunes identified with the colleagues, and Jarrett on his two-disc Tribute (1989), recorded live in Köln, appears to adopt this habit as much as anyone — playing “All of You” as a nod to Miles, “Solar” as a gesture of respect for Bill Evans, “It’s Easy to Remember” as an appreciation of Coltrane, and “I Hear a Rhapsody” to show us how he digs Jim Hall. But when he performs “Just in Time” as a tribute to Charlie Parker, he’s offering something stranger and more challenging. This Comden-Green-Styne tune comes from Bells Are Ringing, a Broadway musical that didn’t even open until the year after Bird died (1956), and although critic Ben Ratliff questions how Parkeresque this up-tempo performance actually is, he does concede the “the piece is festooned with fleet bebop phrases”. But in fact, if you use your imagination to substitute Parker’s alto sax for Jarrett’s piano, you might notice that the way the latter strings his phrases together and pauses briefly between his ideas is distinctly Parkeresque. The fact that “Just in Time” premiered after Parker died is strictly incidental; one can still readily extrapolate the sort of workout he might have given the tune.

Jarrett actually borrows from and/or alludes to other jazz figureheads in a variety of ways, whether he officially signals it or not. When he plays “Poinciana” at a 1999 Paris concert heard on Whisper Not, he’s not only duplicating Ahmad Jamal’s arrangement, tempo, and predilection for upper-register piano keys; he’s also pursuing related riffs (while perhaps playing a few more notes than Jamal would have) and contrasts in dynamics, and getting his expert accompanists Gary Peacock (bass) and Jack DeJohnette (drums) to propel a similar kind of swing. In other words, this is a personal kind of flattery/imitation, and one whose most striking divergence from Jamal would probably be the grunts and sighs expressing Jarrett’s emotional involvement in his solo. But when he plays “Conception” at the same concert, this isn’t exactly a tribute to its composer, George Shearing; for that, he’d probably have to approximate a climax in ecstatic Shearing’s locked-hands style.

Or take Jarrett’s version of “All the Things You Are” on Tribute, dedicated to Sonny Rollins. Rollins is a master of cadenzas, fully capable of spinning out cascading, unaccompanied inventions for protracted periods of uncertain lengths — most often at the very beginning or somewhere towards the end of certain numbers. And one of Rollins’ best ways of generating suspense is to suddenly “get stuck” inside the same couple of bars, improvising to the same chord changes endlessly repeated, inviting us to wonder how long he can keep this up before returning to the standard chord sequence. (These should be considered vamps sustained by the rhythm section — something like the intro to Jamal’s and Jarrett’s version of “Poinciana” — rather than a cappella cadenzas.)

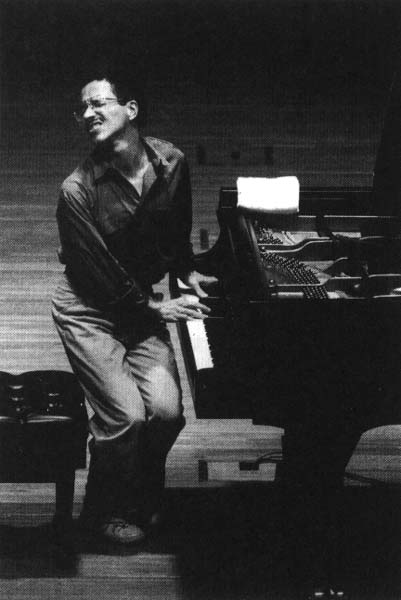

Both of these routines are employed by Jarrett on a regular basis. So what’s so special about his “official” Rollins tribute? This begins with a wonderful and very Rollins-like cadenza before succumbing to the melody; and the eventual arrival of the tune is greeted by applause — a sign of surprised recognition which also frequently happens after one of the free-form intros of Rollins (or Erroll Garner, for that matter). But the previous “Just in Time” ends with an equally Rollins-like vamp section. Could the tribute in this case possibly have something to do with the physicality of Jarrett’s performance, which isn’t visible on a CD? I’m thinking of the kind of trance-like dance of his upper torso that we can intuit and imagine from other Jarrett performances, which corresponds somewhat to Rollins’ occasional practice of walking or pacing around a stage as a kind of visual countermelody to his solos. This calls to mind why vibes players tend to be more pleasurable to watch than musicians performing on any other instrument — because it’s virtually impossible to play the vibes without dancing at the same time. Jarrett’s physical transports occasionally suggest something comparably giddy.

Jarrett notes in the liner notes of his recent Live at Montreaux, recorded in 2001, “the audience was not really ours until we played, for the first and only time ever in concert, three ragtime versions of standard tunes.”

For the record, the first two are Fats Waller songs, “Ain’t Misbehavin’” and “Honeysuckle Rose,” followed by the Rodgers and Hart “You Took Advantage of Me,” and a distinctly Walleresque cheerfulness pervades this entire stretch. “It is a perfect demonstration of our commitment to jazz,” Jarrett adds, “that these do not come off as mimicry or some kind of joke,” and this becomes a key point about his cross-referencing. To mix metaphors and body parts, seeing the world through Waller’s eyes is a particular way of rearticulating and re-energizing the Jarrett touch.