From the Jewish Daily Forward, October 9, 2012. — J.R.

Hollywood’s Chosen People:

The Jewish Experience in American Cinema

Edited by Daniel Bernardi, Murray Pomerance, and Hava Tirosh-Samuelson

Wayne State University Press, 270 pages, $31.95

The coeditors stake their claim in the first sentence of their Introduction: “This book sets out to mark a new and challenging path of the role of Jews and their experience in Hollywood filmmaking.” And to some degree, they live up to this goal, in a varied collection that tends to get livelier as it proceeds. But considering how slippery and elastic their definitions of “Jews” can be, part of their path strikes me as both familiar and questionable.

Fritz Lang, for instance, gets cited over a dozen times in the book’s index, but for me his inclusion is fully justified only once — in a fascinating article by Peter Krämer that charts diverse efforts over four decades to make a movie about Oskar Schindler that preceded Steven Spielberg’s Schindler’s List in 1993, many of them launched by Schindler himself, who had a lengthy correspondence with Lang about the first of these projects in 1951. Virtually all the other references assume that Lang was a Jew because of his mother’s origins—a default position held in spite of his being raised solely as a Catholic and apparently never betraying the slightest interest in identifying himself any other way. This becomes still more debatable when the editors uncritically parrot the standard myth that Lang fled Germany in 1934 immediately after Joseph Goebbels offered him a job as head of a major German film studio. (This is what Lang, the only source for this myth, claimed years later — in a movie-thriller-like narrative that had him dashing off to Paris the same day, before he could even withdraw his funds from the bank; but the various dates stamped on his passport, which included one or more return trips, plus the absence of any allusion to such a meeting in Goebbels’ detailed journals, now make this story seem doubtful.)

Rather like the common practice of identifying Barack Obama as only black (which denies that he had a white mother who raised him), this points to an unconscious process of selectivity in determining who is or isn’t Jewish — a sort of expedient choosiness about electing members of the Chosen People. (As Sarah Kozloff candidly admits in her own essay here, “Playing `here’s a Jew, there’s a Jew’ is an admittedly limited approach to the history of cinematic liberalism, but the links are still intriguing.”) Writer-director Samuel Fuller, unlisted in this book’s index, had immigrant parents named Benjamin Rabinovitch and Rebecca Baum, plus body language that I (rightly or wrongly) identified as quintessentially Jewish the first time I met him. But I suspect he tended to play down his ethnic background in his conversation because of the difficulties this might have posed for his journalistic career in the 1920s and afterwards, so he almost never gets counted as a Jewish filmmaker, even though the theme of racism is central to his work. Charlie Chaplin, another missing name, wasn’t a Jew of any kind except existentially: a good many people thought he was Jewish, and during the whole Nazi period, out of a sense of solidarity, he refused to deny it — which for me counts for more than Lang’s biological background.

Nevertheless, the issue of whether Jewish identity needs to be hidden, brandished, or passively assumed is what gives this collection much of its interest, even if some of the contributors, Jewish and otherwise, might be too cavalier about assuming it in others. This is why Neal Gabler’s provocative 1988 classic An Empire of Their Own: How the Jews Invented Hollywood, describing the American Dream as the creation of East European Jewish immigrants in flight from their own roots, remains this book’s most important precursor.

So notwithstanding some occasional laxness in scholarly details — The Old Man and the Sea miscredited to Fred Zinnemann rather than John Sturges, the assumption that Lang directed Spencer Tracy in more than one performance, the claim that Elaine May and Neil Simon’s The Heartbreak Kid is based on a play rather than a story by Bruce Jay Friedman — this book has provided me with some invaluable history lessons, including Wheeler Winston Dixon’s account of how Hollywood’s major and official censor from 1934 to 1954, the Production Code’s Joseph Breen, could turn out to be a virulent anti-Semite, and David Sterritt’s morally and aesthetically acute “Representing Atrocity: September 11 Through the Holocaust Lens”. Here and elsewhere in the book, the Gableresque theme of how Jews feel about being Jewish — and how both non-Jews and Jews feel about the results of this feeling — provides some of the more interesting and edgy insights.

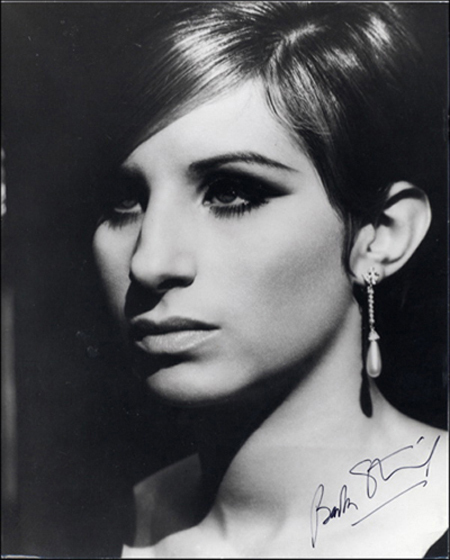

This culminates in a hilarious and very insightful investigation by Vivian Sobchack into her own furious ambivalence about Barbra Streisand, aptly subtitled, “When Too Much is Not Enough,” in which she tries first to account for the extreme and excessive hatred Streisand manages to provoke in some members of her public (Jewish and non-Jewish), then to tease out the anti-Semitic implications and ramifications of some of this hatred, and finally to offer a plausible ideological critique of Streisand’s brand of self-assertiveness as being more conservative and conventional than it initially appears to be.

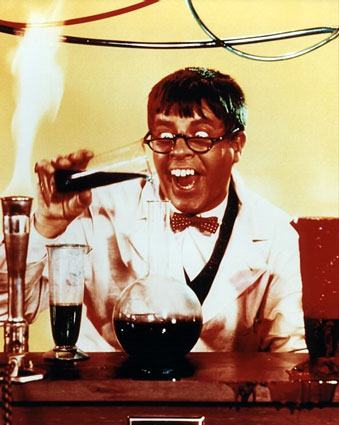

Mutatis mutandis, similar questions are posed by the alternating waves of infatuation and loathing expressed in American culture for Jerry Lewis, with comparable nuances relating to both Judaism and nouveau riche ascendancy as intertwining issues -– the subject of this book’s preceding essay, by coeditor Pomerance, “Who Was Buddy Love?: Screen Performance and Jewish Experience”. This does an intricate job of analyzing Lewis’ separate Jekyll-and-Hyde identities in The Nutty Professor: the more Jewish, sweet-tempered, and terminally klutzy title figure of Julius Kelp and the more goyishly assimilated and boorishly confident swinger-type, Buddy Love, whom the public seems to prefer. In the case of Streisand, however, these opposite types appear to be paradoxically combined via a kind of shotgun marriage into a walking, talking, and singing contradiction.

What seems so fascinating about Lewis and Streisand as public Jewish figures with fearless in-your-face profiles and hyperbolic success stories is the mythical assumptions, irrational attitudes, and conflicting emotions they seem to provoke in others. (The obsessive mantra about “the French” loving Lewis, already exaggerated to begin with, is by now roughly half a century out of date: Woody Allen is vastly more popular in France, and even in the 1950s Lewis was never as popular there as he was in the U.S., where the Martin and Lewis craze was sufficiently huge to yield two features per year. So, as with Chaplin, American hatred of Lewis seems to encompass a strange denial that he was ever loved here in the first place.)

Part of what makes this book’s Pomerance and Sobchack essays score are their autobiographical aspects, and these also crop up beneficially in William Rothman’s reflections about the great Hollywood director George Cukor and Sarah Kozloff’s thoughts about Susan Sontag’s conflicted stances regarding “Jewish moral seriousness” in American movies, making it a lot easier to anchor their shifting arguments. I immediately bonded with Rothman when, writing about Cukor’s Hungarian Jewish background, he noted, “He had a bar mitzvah, but I assume he learned the Hebrew for his reading only phonetically (as I did in my Reform synagogue in Brooklyn half a century later)”–- which is pretty much the way it went for me at my Reform temple in Florence, Alabama in 1956, probably around the same time.

During that same era, when WASP ingénue Debbie Reynolds fell in love with Jewish crooner Eddie Fisher, who then ran off with WASP star Elizabeth Taylor — occasioning a multicultural scandal in the movie fan magazines, expertly chronicled and glossed here by Sumiko Higashi — this could surely be described as yet another staged form of mainstream assimilation writ large.

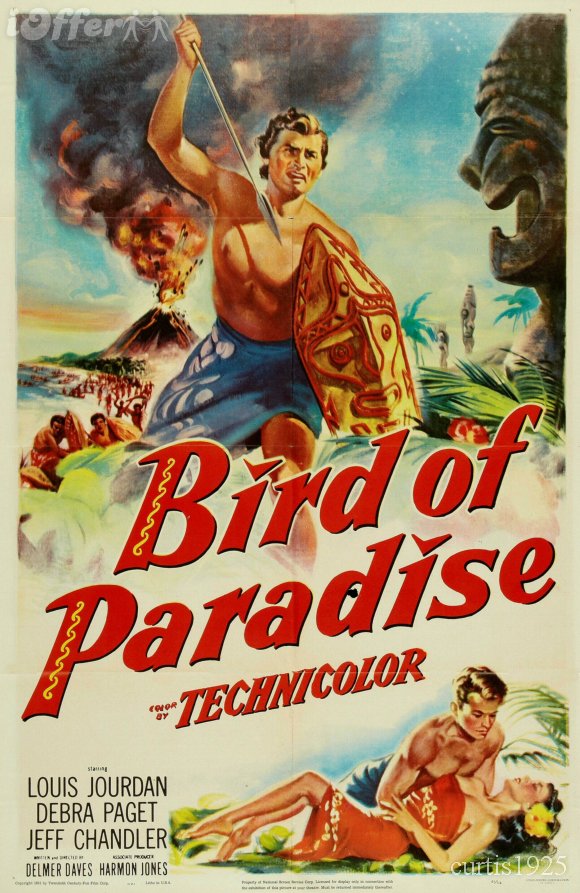

In 1954, a nightmare of mine fed by the combined fury of sibling rivalry regarding my older brother’s bar mitzvah and troubled memories of Bird of Paradise, a gaudy 1951 Technicolor fantasy about the tribal sacrifice of a South Sea Island maiden, actually caused me to lose my religious faith, a process I tried to come to terms with in my autobiographical first book, Moving Places: A Life at the Movies. Moreover, the fact that the tribal chieftain was played by a Yiddish actor, Maurice Schwartz, may have unconsciously spiked the alchemy of my overheated imagination. So when Pomerance notes that his own “first Jew of the screen”– in Hamilton, Ontario circa 1954 — was Abraham Sofaer in His Majesty O’Keefe playing Fatumak, a Pacific island medicine man, I know exactly what he means and even a bit of how he felt.That is to say, the diverse movie fantasies and cultural reflexes created by and for assimilated Jews took and take many exotic as well as prosaic forms, and this spirited anthology manages to unpack a suggestive sampling of them.