From Film Comment (January-February 2001). –- J.R.

I blush to admit that I’ve still seen only half the eight features to date of Ousmane Sembene, made over a 33-year period as a supplement to his dozen or so volumes of fiction. Yet considering how difficult it generally is to track his remarkable and varied work on film or video that comes ridiculously close to qualifying me as an expert. (The fact that it typically takes a couple of years for a new Sembene film to reach these shores is commonly perceived as an African as opposed to American form of inertia, but I would think the responsibility for this state of affairs might be shared.)

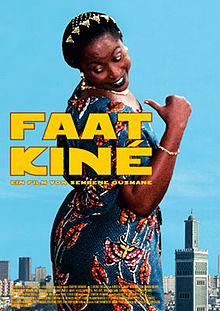

The first and in many ways still the greatest of all African filmmakers — give or take a masterpiece or two each by Yousef Chahine, Souleymane Cissé, and Djibril Diop Mambety, among others — Sembene, born into the Senegal working class in 1923, started out as a gifted novelist who turned to filmmaking at the age of 40 chiefly in order to address more Africans. Yet because he’s a storyteller who regards film more as an extension of his prose than as an abstract calling, one of the clearest pleasures to be derived from his work is his propensity for reinventing the cinema – his own and everyone else’s — every time he embarks on a new feature. There are a few obvious signs of stylistic continuity, such as a no-nonsense way of leaping into flashbacks whenever he has to account for certain character traits or backstories, epitomizting what the great literary critic Erich Auerbach called Homeric style. There are also certain thematic constants, such as an interest in women’s issues, extending all the way from his first feature, the terse 1966 tragedy Black Girl, to the laid-back comedy of his new film, Faat Kiné. Otherwise Sembene refuses to build on earlier pictures the way that directors like Ford, Ozu, Godard, or Kiarostami do. Without a trace of either pretension or cinephilia each time out, this playful OId Master arrives at a new “amateur’” version of what movies are simply in order to come to grips with his particular story and characters; and at 76 he’s clearly having a ball.

In fact, the film’s title character, Faat Kiné, is a lulu: a sassy, ebullient 40-year-old manager of a gas station (energetically played by Venus Seye). Born the same year as Senegal’s independence, she lives with both her crochety old mother, Maamy (Mame Ndumbe Diop), and her two illegitimate children (from separate fathers), Djip (Ndiagne Dia) and his older sister, Aby (Mariame Balde), both of whom have just passed their college entrance exams. Kiné‘s youthful dream of becoming a lawyer or judge was dashed after she got ditched by both her school and father for becoming pregnant (courtesy of a philosophy teacher, whom Djip treats scornfully at a party), but she’s managed to give her own relatively spoiled kids the perks that were denied to her. A character with the kind of nervy pride one might associate with a John Waters heroine, she comes into her own after the wife of a sometime-lover sashays up to her car window and starts to make threatening noises: “Listen, if I catch you sleeping with him, I’ll kick your ass and put pepper in it.” After pausing to take this in, Kiné emerges from her car, asks the woman to repeat her threat, promptly squirts pepper spray into the woman’s eyes, and declares, “Who are you to talk to me like that? When I need a man, pay your husband for his services.”

Significantly, this little explosion is delivered in one of Senegal’s native tongues (most likely Wolof) rather than in neocolonial French – unlike most of Kiné‘s other verbal inventions, which are almost literary by comparison. When her son’s father –who cheated her out of a down payment on a house with a spurious marriage proposal, then got picked up with false papers while trying to leave the country – chides her for not even bringing him a plate of rice in prison, she replies, “You would have shit that rice like steel nails burning through your gut.” And to an appreciative bank manager admiring her “caboose” she boasts, “Top-of-the-line caboose –- not for public transport.” “Maamy always says our generation of women is affluent and confluent,” she quips in French to a friend, and this appears to be true: she has a dutiful maid at home and loves to banter about condoms, Viagra, and hard-ons with her pals.

When Louis Aragon — a fellow militant in the French Communist party during the Nazi period — once said to Sembene, “The French language is my country,” the African writer shot back, “For me, it represents both an internal and external exile.” Yet Faat Kiné, Iike Sembene’s earlier pictures, shows that he can use both French and cinema as naturally as a loose-fitting change of clothes. Mutantis mutandis, Howard Hawks in his own African picture, Hatari, uses narrative in roughly the same fashion — as a way of enjoying his characters and spending some time with them.

Among the many topics coursing through this rich comedy of manners — as busy with locals and subplots as a Jacques Demy musical — are the everyday operations of a gas station, the differences between being Islamic and being Catholic (including the distinction between polygamy and monogamy), and the seeming incongruities of traditional African life persisting in a modern capital like Dakar. The latter is highlighted in the credits sequence, in which a procession of brightly garbed women carrying baskets and babies crosses a busy intersection, briefly passing Sembene’s heroine in her car as she drives her kids to their exams. This time around, the concentration on African history underlining Sembene’s last two features, Camp Thiaroye and Guelwaar, is located exclusively in the present, where anger often gives way to admiration and amused wonder — a feeling of hope about Africa’s future, which might even be saved by its stubborn women.