From the July 21, 1989 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

LET’S GET LOST ** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Bruce Weber.

“Can you carry a tune? Is your time all right? Sing! If your voice has hardly any range, hardly any volume, shaky pitch, no body or bottom, no matter. If it quavers a bit and if you project a certain tarnished, boyish (not exactly adolescent, almost childish) pleading, you’ll make it. A certain kind of girl with strong maternal instincts but no one to mother will love you. You’ll make it. The way you make it may have little to do with music, but that happens all the time anyway.”

This is jazz critic Martin Williams 30 years ago in a Down Beat review of It Could Happen to You: Chet Baker Sings. By this time, the youthful Baker had already established a reputation as a jazz trumpeter of some promise, and later in the same review, Williams concedes that as an improvising musician, he has a “fragile, melodic talent” that is “his own,” even if he “has hardly explored it.” The same strictures might apply to Let’s Get Lost, Bruce Weber’s spellbinding (if simpleminded) black-and-white documentary about the life, times, and last days of Chet Baker. The movie has a number of things going for it, but music plays at best only an incidental role. Deliberately or not, the film actually acknowledges this. Although we hear a great deal of Chet Baker’s singing and trumpet playing, it’s almost completely relegated to the status of dreamy background music; a talking head invariably takes over after a few bars, and the music — which seldom continues for the length of a whole solo, much less an entire number — is meant to function only as moody accompaniment to the gab in the foreground. (The only scene that contains a complete number shows Baker in close-up, at far from his best, singing “Almost Blue” at a Cannes nightclub in 1987, not long before his death at the age of 58.) We do hear snatches of Baker’s playing from much of his career, but curiously enough — or perhaps not so curiously — these snippets don’t include any of what most jazz aficionados would regard as his most important work, his strikingly innovative recordings with Gerry Mulligan’s pianoless quartet in 1952.

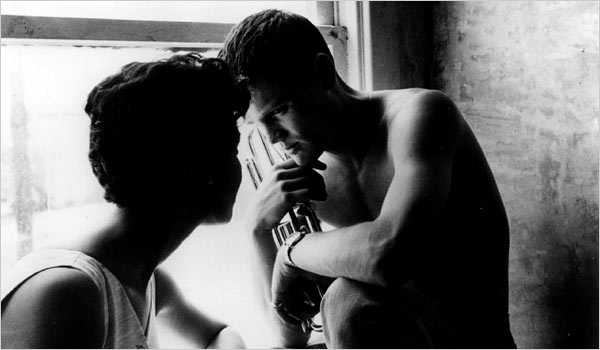

Listening to some of those sides recently, I was newly struck by their Spartan rigor. Without a pianist or guitarist feeding them chords, Mulligan and Baker — modernist in the bone-dry ironies of their solos and contrapuntal duets, yet traditionalist in their melodic sources — sound like the musical equivalent of tightrope walkers without a net. Set off by the gentle growls of Mulligan’s baritone sax, Baker’s trumpet, which was always a much richer instrument than his voice, combines some of the cushiony tone of Miles Davis with a lyricism harking back to Bix Beiderbecke; and if the overall range of invention is fairly narrow (as it always would be), there’s hardly a trace of the little-boy pathos that would later come to dominate his work. For all its deceptive simplicity, it doesn’t work as cocktail music or ambience, which is conceivably the reason Weber hasn’t included even a sample of it on his sound track; for better or for worse, one has to listen to this music straight, without mixers or chasers. The obsession with Baker that permeates Let’s Get Lost has much more to do with his power as an icon than his talent as a musician. “He was bad — he was trouble and he was beautiful,” declares a female admirer early on in the movie, and this seems to sum up Weber’s infatuation as well. A clean-shaven Adonis who embodied many of the same 50s myths that circulated around James Dean (a comparison that was enhanced by Baker’s taste for fast-moving sports cars), and who still sang with an Elvis-like sneer when he appeared on Steve Allen’s TV show in 1968, Baker became a junkie early on, and the remainder of his life, as depicted by the film, was an endless string of speedballs, busts, relapses, deportations, broken relationships, and related vicissitudes. When Baker won first places in the Down Beat polls during his mid-20s –as trumpet player in 1954 and 1955, and tieing with Nat “King” Cole as best male singer in 1954 — he had arguably passed his peak already, but his image and legend kept him going for at least three more decades. As jazz journalist Mike Zwerin put it, “The creases on his face multiplied and deepened and his lips turned in over the dentures he had worn since his teeth were knocked out by angry dealers in San Francisco. He began to resemble an old Indian, the last of a tribe that had seen a heap of suffering. He looked like he needed taking care of and he did and there were always people around to do it.”

By the time Weber came to make a movie about Baker, in 1987-88, his face resembled a relief map and his manner was that of a burnt-out hipster on his last go-round. The poignance in the difference between the Adonis and the human wreck that emerged from him is what the movie exalts and circles around in endless morbid fascination; and thanks to the spell exerted by Jeff Preiss’s noirish high-contrast photography and the background purrings of Baker himself, it is very difficult not to share the fascination. But sharing the fascination entails involvement in a romantic cult of personality that cheerfully acknowledges all of Baker’s many shortcomings — his wife-beating, for instance — without letting them interfere with an unbridled adoration of his persona. As Pauline Kael (among others) has pointed out, the movie is fundamentally about Chet Baker the fetish, the love object, so it shouldn’t be surprising that it comes across as a personal scrapbook. There’s a striking disingenuousness in the way that Weber, offscreen, asks Baker’s mother, “Did he disappoint you as a son?” (“Yes,” she replies, “but let’s not go into that”); he virtually encourages some of Baker’s former wives and lovers to trash one another. Baker’s daughter by his third marriage recounts with visible relish stealing clothes and jewelry when she was 14 from the jazz singer Ruth Young, who supplanted her mother in Baker’s affections; Baker’s first two wives and eldest son declined to be in the film, but his third wife and at least three girlfriends are interviewed at length.

Clips from a couple of dinky films that Baker appeared in — Hell’s Horizon (1955) and an unnamed Italian pop item of 1959 — as well as a Hollywood picture, All the Fine Young Cannibals (1960), allegedly inspired in part by his life, are offered reverently as supplementary objects for contemplation. In his lengthy analysis of the appeal of Judy Garland to gay men in his book Heavenly Bodies: Film Stars and Society, Richard Dyer places particular emphasis on Garland’s “emotional quality,” her vulnerability and suffering, her courage in continuing to perform publicly in spite of her many problems (“marriage, weight, drugs”), the ordinariness of her MGM image, her androgyny, and her expression of camp attitudes. With the exception of weight problems and camp attitudes, the sources of Baker’s appeal as a romantic image are nearly identical — so much so that when I originally saw Let’s Get Lost last fall at the Toronto film festival, I described it to friends as “The Judy Garland Story.” Since then, Weber’s film has gone on to become an enormous cult success in New York, although I’ve seen little evidence that the cult in question is exclusively or even specifically gay. What this may suggest is the resurfacing of what could be described as a “gay sensibility” in mainstream terms — a phenomenon that is also apparent (albeit somewhat differently) in the undertones of recent hits like Rain Man, Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, and Batman, where most of the significant erotic tensions exist between men rather than between men and women. Perhaps it’s a side-effect of the enormous wave of psychosexual repression brought about by AIDS in the populace as a whole, but it appears that homoeroticism has been assuming a centrality in mainstream culture and is only called into question when it is overtly perceived as “gay.” Weber’s work as an art and fashion photographer and his previous film Broken Noses, a documentary about little boys in a boxing match, illustrates the same sensibility; the issue isn’t Weber’s sexual orientation or that of his audience, but the notion of what’s fashionable and alluring that informs his work.

In some respects, Let’s Get Lost could be regarded as a dumb film about a less than brilliant individual, but this has so little relevance to its unmistakable appeal that I feel like a spoilsport for bringing it up. It’s certainly dumb, for instance, for the film to give us a vest-pocket history of stars appearing at the Cannes Film Festival over the years — a history justified solely by Baker’s appearance at a nightclub during the festival in 1987 (where he incidentally remarks on the noisiness and inattention of his audience). But emotionally and fetishistically speaking, the archival Cannes footage makes perfect sense because it helps to establish Baker as a Cannes star in his own right, right up there with Jean Cocteau and Brigitte Bardot — a star not because of his talent but because of the romantic investment that Weber has in his image, even in its degradation. The film draws much of its appeal from the colorful gallery of friends, groupies, and diverse hangers-on (including a litter of adorable puppies) accompanying Baker and the film crew on his travels. Jazz trumpeter Jack Sheldon offers a couple of hilarious deadpan monologues about Baker, and Ruth Young — a singer, like Baker, in the Chris Connor/June Christy mode, and judging from the limited evidence a much better one than her former boyfriend — shows an equal amount of liveliness and intelligence; a few of the others have pertinent things to say as well, but most of the commentary is as walleyed and as bubbleheaded as the film itself — full of awe about very little, unless one confuses the idea of Chet Baker with Baker himself. A decade ago Wim Wenders embarked on a related sort of project, when he and the late Nicholas Ray, who was dying of brain cancer after a comparably disheveled life, made a film about Ray’s last days entitled Lightning Over Water. While Ray was a much more important figure in film than Chet Baker was in jazz, his achievements were many years behind him when this filmic act of witness was undertaken; and even though Wenders’s attitude toward Ray as a spiritual father was every bit as romantic as Weber’s attitude toward Baker, the film didn’t deal with its subject in such a seductive way. Stark, painful, and upsetting in both of its two released versions (the first of which is currently available on tape), Lightning Over Water was more an act of defiance than a tribute — on Ray’s part as well as Wenders’s — and it raised more questions than it answered, with none of the dreamy conceits that make Let’s Get Lost so appropriately titled. A failure almost by definition, it was nevertheless a serious effort that commanded respect and attention, if not love. Let’s Get Lost exudes as well as commands a great deal of love, but respect and attention are not what it has to offer.