A commissioned review for Sight and Sound, published in their November 2021 issue. –J.R.

Texas, 1980. A year after firing him, rodeo boss Howard Folk rehires ex-rodeo champ Mike Milo to retrieve his son Rafo from his abusive mother in Mexico City. In a Mexican village on the way back, Milo teaches Rafo how to ride horses and becomes enamoured with a friendly widow.

Regardless of what he may have intended in White Hunter Black Heart, Clint Eastwood’s neo-Brechtian, autocritical lead performance—Eastwood playing Eastwood imitating John Huston—remains one of his more telling gestures. It evokes Charlie Chaplin and Marilyn Monroe exploring the darker sides of their own charisma as Henri Verdoux and Lorelei Lee, though Eastwood’s minimalism gives him far less to work with (or critique). He musters even less at age 91 as Cry Macho’s Mike Milo, ex-rodeo saddle tramp–a much older, lamer version of Robert Mitchum’s Jeff McCloud in The Lusty Men, mauled by horses, bulls, and drugs and booze to kill the pain of their having landed on top of him.

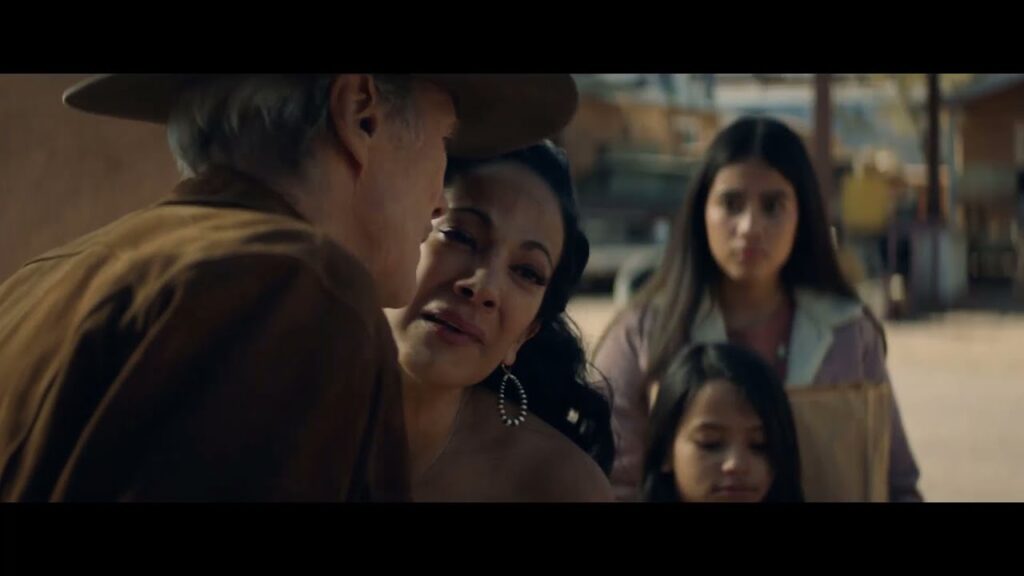

Kidnapping 13-year-old Rafo in Mexico City from his abusive Mexican mother for his former boss, Rafo’s wealthy father, and driving the boy back to Texas, Milo finds redemption by hanging out with friendlier Mexicans and animals in the boondocks. During his two weeks there, he regains traces of the family life he once had, tames wild horses while showing Rafo how to ride them, and advises locals about how to care for their ailing animals, enjoying a warm community he’s obviously happy to return to.

Eastwood’s no Charlie Chaplin, yet one can still say that he comes closer to the plain-talking directness of Chaplin’s dethroned king in A King in New York than to the commercial misjudgment of his Countess from Hong Kong, arguably a rough equivalent to Eastwood’s dialogue with an empty chair at the 2012 Republican National Convention. More plausibly, nine years later, he’s responding this time not to Barack Obama but to Donald Trump. Even without our knowing how he voted in the last Presidential election, it’s hard to ignore the affectionate feelings aired here about Mexico and Mexicans, simple country folk versus angry tycoons, bonding with animals and sleeping outdoors, not to mention attitudes that are against xenophobia and skeptical about both macho positioning and capitalist investments. In contradistinction to Trump’s mockery of the disabled, Milo even communicates by sign language with a widow’s deaf granddaughter. In short, one might wonder if this one-time mayor of Carmel, California is joining the ever-expanding ranks of anti-Trump Republicans yearning for a more civilized country (in this case, Mexico).

However accurate certain quibbles may be about clumsy exposition, unconvincing plot twists, uneven acting, and other technical gaucheries, some of these hardly seem to matter. (Not all of them, however. Rafo is insufficiently fleshed out in both script and performance, and Milo’s lost wife and son only merit a belated blip in the dialogue.) By now, Eastwood has earned a certain complicity with his audience that can sail past some of these imperfections as passing glitches.

This isn’t the first time he’s addressed the historical present in a period plot (mostly set in 1980): it was hard not to view Flags of Our Fathers and Letters from Iowa Jima as commentaries on recent U.S. military exploits. Cry Macho—based on a script that had been kicked around Hollywood for decades, recently revised for Eastwood—can’t resist making its two leading ladies hyperbolically smitten with Milo as a sexual or romantic partner, which would have been more palatable a few decades back. Yet despite Milo’s claim to Rafo that “the macho thing is overrated,” Eastwood is not yet ready to throw out his own macho with the bathwater, and even adds a celebratory cock crow to his director-producer credit at the picture’s end.

Macho is the name given by Rafo to his cockfighting, breadwinning rooster, a fair enough stand-in for Eastwood’s younger persona and meal ticket. The very title Cry Macho expresses Eastwood’s wisened ambivalence about macho, seen now more as boyish plea than as meaningful acquisition. Like his slowpoke hero, he’s not so much a cowboy as a faded, fragile remnant of cowboy myth who’d rather settle down peacefully than engage in slugfests. The obligatory action interludes, furnished by Mexican cops or henchmen sent by Rafo’s mother to impede the journey to Texas, mostly register like interruptions—rather like the Dirty Harry romps dutifully delivered by Eastwood to finance his art movies –although at least the landscapes are attractive.

Not a major Eastwood picture, Cry Macho is none the less an agreeable one, especially in the way it periodically seems to forget its own plot in order to dispense its soft-pedalled life lessons. How agreeable it is ultimately depends on how much one believes in the lessons.