From Monthly Film Bulletin, November 1974 (Vol. 41, No. 490). — J.R.

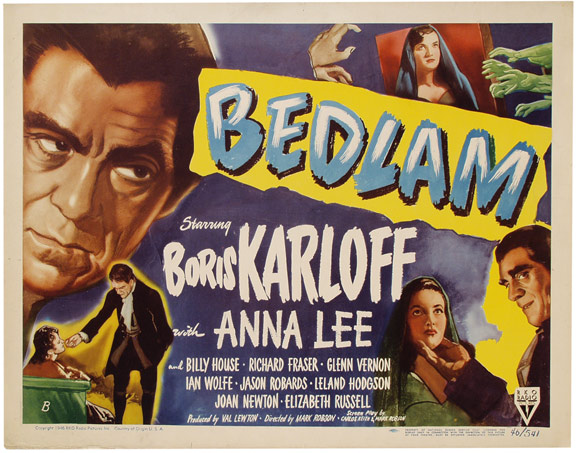

Bedlam

U.S.A., 1946 Director: Mark Robson

London, 1761. Attempting to escape from the St. Mary of Bethlehem lunatic asylum, commonly known as Bedlam, a poet named Colby is forced by Sims, the apothecary general in charge, to drop from a railing, and he falls to his death. Lord Mortimer and his ‘protégée’ Nell Bowen, passing by in a carriage, question Sims about the incident, and are assured it was an accident. After subsequently paying a visit to the asylum, Nell is appalled by the living conditions and Sims’ sadistic treatment of the inmates, and appeals to Lord Mortimer to make a charitable donation. But Sims dissuades the latter from doing so. When Nell joins forces with John Wilkes to turn the cause into a political issue, Sims contrives to have her declared insane and committed to Bedlam. Frightened for her safety — and securing a trowel from Hannay, a sympathetic Quaker brickmason, for protection — she none the less elicits the respect and loyalty of the other inmates, and when Sims locks her in a cage with a supposedly dangerous lunatic, she successfully placates her cellmate. The trowel has meanwhile been mysteriously stolen. When Sims threatens to subject her to a ‘treatment’, before a hearing to reconsider her sanity is held, the other inmates capture him and hold a mock trial. He is judged to be sane, but just after he is released, he is stabbed by a female inmate with the stolen trowel and then sealed in a chamber that is mortared up with bricks by the inmates. Nell and Hammay are happilyreunited, and look forward to improving the lot of the mentally ill.

Initially banned in England, and finally making its appearance some twenty-eight years after its American release, Bedlam is a disappointingly weak and lackluster Val Lewton effort, particularly in relation to the more celebrated films that preceded it. In a project that cries out for the dark ‘period’ imagination of an Anthony Mann or a James Whale — or barring that, some of the baroque atmosphere of a John Brahm — one is offered some semblance of the characteristic Lewton virtues (taste, reticence, literate if overly fancy dialogue) without a style or vision forceful enough to weld them together into something meaningful. Sagging not a little under the weight of its honorable intentions, the film seems to suffer from a network of counter-strategies, all effectively working against each other. In an enterprise claiming as its departure point a moral objection to ‘looking at the loonies’ for entertainment, it is singularly unconvincing to pursue this concern while half-heartedly attempting to hold the audience’s attention with entertaining inmates. One suspects that such an inconsistency derives more from confusion than from impure motives — indeed, a greater amount of duplicity or sheer bad taste might have given the film more life than it has. As it stands, Bedlam is too cautious and tentative about its vaguely educational aims to carry much moral or amoral force, although it skitters about fitfully in both directions. Its vision of good, as incarnated by Hannay, seems hopelessly square and stilted (“I’m a stonemason. I build well. Let other people build well and this city will become a clean and pleasant habitation”), while its vision of evil — left to Karloff’s Sims — consists of arbitrary and seemingly obligatory acts of malice or pronouncements of humorless sarcasm pumped into the plot in order to keep it going. The beauty and energy of Anna Lee is regrettably not bolstered by the sort of direction that can sustain a performance, much less a film: Joel E. Siegel reports that one of her dresses is a “Vivien Leigh hand-me-down from Gone With the Wind“, and there’s a teasing Scarlett O’Hara ambience about her playing which doesn’t jell too well with the Florence Nightingale role that the script eventually requires her to assume — an overtone that becomes especially jarring in her scenes with the stolid Richard Fraser. Karloff does what he can with a pasteboard part, underplaying his effects, while Billy House registers as a poor man’s Eugene Pallette; the self-contained elegance of Ian Wolfe in a more modest lunatic part, however, proves that precision in small matters is a worthy achievement even in the murkiest of circumstances.

JONATHAN ROSENBAUM