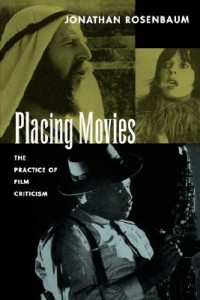

This is the Introduction to the second section of my first collection, Placing Movies: The Practice of Film Criticism (University of California Press, 1993). I’ve taken the liberty of adding a few links to some of the pieces of mine mentioned here which appear on this web site. — J.R.

I should begin here with a somewhat embarrassed confession about a methodology I have employed with increasing frequency, especially since the mid-1980s — the practice of recycling certain elements from my earlier criticism. On a purely practical level, it can of course be argued that very few people who read me in, say, the Monthly Film Bulletin in 1974 are likely to be following my weekly columns in the Chicago Reader two decades later, and that my pieces for Soho News in 1980 (to cite another random example) are not likely to have survived in the periodical collections of many libraries. But I still blush to admit that, in a hatchet job I performed on Donald Richie’s book on Ozu for Sight and Sound in 1975, I sharply reproached Richie for reusing the same phrases about Ozu again and again in his own criticism. This was written at a relatively early stage in my own career when I imagined other film buffs like myself going to libraries and reading virtually everything in print on a given topic; I didn’t really think through the implications of writing about the same films and filmmakers for different audiences in separate countries over many decades — as Richie had certainly already done at that point, and as I have subsequently done. Maybe we’re both lazy, but it seems to me that the degree of purity I was expecting is both unreasonable and unrealistic, especially when it comes to freelance writers; Michel Ciment suggested as much in the pages of Positif when he commented adversely on my presumption.

To be fair to myself on this score, I usually don’t plagiarize myself literally (as some writers are wont to do) when I carry out this practice but, rather, use something I’ve already written as a starting point or springboard — something to get my writer’s crank in motion, as it were. (As an excellent cure for writer’s block — at least if one is working on the same piece in more than one sitting — I can recommend starting each work day by either revising or simply retyping the final page of one’s last work session, which often allows the momentum of one’s previous efforts to carry one over the rough spots into fresh material.)

In the case of my article on Râúl Ruiz in the next section, however, the material went through four stages or incarnations. It began as a relatively short piece written for the January 1985 Monthly Film Bulletin; then some elements from that piece were used in another short article commissioned by the Toronto Festival of Festivals for a bilingual booklet (English and French) devoted to a retrospective called “Ten to Watch.” Then I did a much longer piece for volume 3 of Cinematograph in 1987, edited by my friend Christine Tamblyn— an annual publication of the San Francisco Cinematheque which encourages a certain amount of formal experimentation; and finally, I revised and updated this piece slightly for the January 1990 issue of Noah Forde’s wonderfully eclectic and occasional Los Angeles film magazine, Modern Times, in the version reprinted here.

My second contribution to Cinematograph, written for volume 4, edited by Jeffrey Skoller — an issue devoted to nonfiction film —was “Orson Welles’s Essay Films and Documentary Fictions: A Two-Part Speculation,” probably the most formally playful of the articles in this section. As with the Ruiz piece, part of the reason for the formal play was an attempt at mimetic criticism — that is, an attempt to reproduce some of the formal and stylistic qualifies of the work I’m describing (an ambition that can be found to varying degrees elsewhere in this collection, in pieces on Godard’s criticism, Bartres, Farber, MÉLO, and Rivette, among others). But another part, I should confess, came from a more purely formalist and even capricious desire to follow certain arbitrary rules and patterns in creating a series of mirroring structures between the various sections of the piece. This is why, for instance, the first two sections begin with “two propositions” that are followed by two lists — the first list containing twelve items, the second containing twenty-four. Then, after two more sections dealing respectively with THE FOUNTAIN OF YOUTH and FILMING OTHELLO (each of which, I should add, represents recycled material — the first, an article written for the 1986 National Video Festival catalog; the second, program notes written for New York’s Film Forum in 1987), the last two sections and the final section devoted to footnotes are all built around lists containing eight items each. If a thematic excuse for this exercise is needed, I suppose it could be argued that the mirror structures have bearing on both the arbitrary nature of separating fiction and nonfiction that affects film criticism in general (and some Welles criticism in particular) and the sense of formal play that I find in much of Welles’s work.

“Work and Play in the House of Fiction,” my last major effort written in Paris before I moved to London, is the result of my obsession with two of Jacques Rivette’s films, OUT 1: SPECTRE and CELINE AND JULIE GO BOATING, which I had been seeing, reseeing, and compulsively discussing in Paris with my best friends at the time — Eduardo de Gregorio (Rivette’s screenwriter during this period, who worked on CELINE AND JULIE ), Gilbert Adair, and Lauren Sedofsky — for most of that year. With Gilbert and Lauren, I had just interviewed Rivette in my Left Bank apartment for Film Comment, and I had greatly benefited from being able to attend several private screenings of the work print of CELINE AND JULIE and many showings of OUT 1: SPECTRE during its brief commercial run at Studio Gît-le-coeur.*

________________________________________________________________ *As further signs of my Rivette mania, the following year, thanks to Eduardo, I twice flew from London to France to watch several days of the shooting of the next two Rivette films — DUELLE in Paris and NOROÎT in Brittany. My last sustained work in London was editing a collection of Rivette texts and interviews for the BFI and organizing a “Rivette in Context” season at the National Film Theatre; two years later, in New York, I presented a revised version of this season with Jackie Raynal at the Bleecker Street Cinema. I had not, however, attended the only public screening ofthe 760-minute work print OUT 1: NOLI ME TANGERE in Le Havre three years earlier, and another fifteen years would passbefore I was finally able to see the film — to my mind Rivette’sgreatest — in a finished (i.e., fully processed) print, at the Rotterdam Film Festival in early 1989. Apart from the fact that forty-five minutes of the sound track were still unlocated at thisstage, this was the film’s world premiere, and its presentation atRotterdam was one of the last great efforts of Hubert Bals, the festival’s director, who had died the previous July. But, sad to say, my eventual catching up with this masterpiece occurred during a period that can only be described as postcinematic: only two otherpeople stuck it out for the entire screening (it was shown over two or three days, as the consecutive reels arrived from France), andeven after the film later resurfaced on French and German television as an eight-episode serial and in other European venues,it was almost entirely ignored. Not even Cahiers du Cinéma couldbe bothered to write about it, though it strikes me as being the key film about the 1960s. Apparently we’ll have to wait for a more aesthetically and historically enlightened era for the film to be discovered and appreciated for its staggering achievement. [2014: As of now, it seems fairly safe to say that this era has arrived, at least for many viewers; the film is even available with English subtitles in a German DVD box set.]

The inclusion of one personal memoir (about Tati) in this section raises the wider question of what role this kind of material can or should play in criticism. The value of knowing something about an artist’s intentions as well as various forms of production, preproduction, and postproduction information has to be weighed against the potential danger of such material supplanting criticism entirely and becoming indistinguishable from publicity — the “infotainment” syndrome and the cult of personality where intentionality (whether that of the artist or the publicist) reigns supreme and the groupie mindset is seldom far away. In the establishment of auteurism during the late 1960s and early 1970s, the role played by interviews with directors — in the pages of such magazines as Cahiers du Cinéma, Positif, and Movie, as well as in such books as Truffaut’s Hitchcock and Peter Bogdanovich’s interviews with Hitchcock, Hawks, Lang, and Ford — was perhaps even more influential than the role played by reviews and critical essays.

I’m very much of two minds about this issue. As is obvious from this book so far, my criticism tends to be highly partisan and even promotional when it comes to certain filmmakers I support. Part of what pushes me in this direction, however, is a desire to be heard at all against the onslaught of mainstream media promotion and hype that dominates our film discourse — and dominated it long before the relatively recent rise of infotainment. In other words, against the argument that Godard is his own best publicist and that his spiels are therefore inappropriate as critical tools in evaluating his work, one has to consider the fact that the massive amounts and reaches of publicity accorded to much less interesting and talented filmmakers have lulled most critics into docile acquiescence, which suggests that “mere” publicity for the work, ideas, and even personality of Godard constitutes a critical and even polemical act in such a climate. Considering both the extent to which all “coverage” is promotional in one way or another and the monstrous inequities that exist whenever money is concerned (which is virtually always when it comes to film), I’ve never considered it to be an ethical problem in promoting relatively unpopular or unknown work over relatively popular and well-known work, because most of the mechanisms that promote popularity and knowledge in movies have nothing whatsoever to do with critical values.*

_______________________________________________________________

*After my piece on KING LEAR appeared in 1988, I received a note from Tom Luddy, the producer, informing me that he’d sent the piece to Godard, who told him to tell me that he really liked it.Considering Godard’s customary reticence on such matters, I can think of few compliments that I’ve treasured more.

As one extreme example of these mechanisms, let me cite the curious case of my dealings with the Chicago office of Warner Brothers, which did not invite me to any of its press screenings for nearly three years — the only local film company that has ever behaved in such a fashion, and one whose policy in this matter was initially confirmed and protected on the highest multinational levels of Warner Communications. The reason for this blackballing was an incident that occurred in early 1991. A local film critic called one day to reschedule a lunch date because he wanted to attend a screening of NEW JACK CITY that had just been set up. I hadn’t been invited to the screening, and when I asked my friend if he thought I could attend it myself, he suggested I call Warners’ local publicist, but asked me not to reveal who had told me about the screening, which was supposed to be a secret. The publicist, a Warners employee since the late 1950s, is known among Chicago film critics for his sensitivity about such matters, but I decided it wouldn’t hurt to ask. I was sadly mistaken.

When I phoned the publicist was out, so I asked his assistant if I could attend, and she didn’t imagine there would be any problem. About an hour later, however, my phone rang, and when I picked it up the publicist began screaming at me and demanding to know who had told me about the NEW JACK CITY screening. I said I didn’t remember, and when he persisted in badgering me I came up with the name of one of the most prominent local critics — not the one who had told me, but one who I thought was least likely to be hurt by being named. “You’re lying!” the publicist screamed, and went on to explain why he knew I was lying before hanging up on me. A few minutes later he rang up again and screamed at me some more. I told him I had only called in the first place to ask if I could attend the screening, and if he didn’t want me to come, I wouldn’t. He said he didn’t want me to and hung up again; my name was promptly removed from the invitational list for Warners screenings. A few weeks afterward, I recounted the above story in my Reader column about GUILTY BY SUSPICION, a Warners feature about the Hollywood blacklist (see “Guilty by Omission” in part 5), not merely as a relatively trivial example of how it felt to be blacklisted, but also as a sort of mea culpa regarding my own unheroic behavior in the incident — the fact that my first impulse was to lie to the publicist rather than openly defy him, as I did later. About two years after this column appeared (as well as a subsequent and relatively uninformed story in Variety about the original incident), the chairman of the National Society of Film Critics wrote a friendly letter to the publicist on my behalf, mentioning in passing that my paper had a circulation of about a third of a million. About a year afterward, in early 1994, after both the chairman and Michael Wilmington of the Chicago Tribune made further appeals to Warners’ west coast office on my behalf, I was finally invited to Warners screenings again. (Prior to that, I still saw and reviewed some Warners films, usually a week or more after other reviewers, but wound up missing more of their movies than those of any other major studio.)

The point of such an aberrant anecdote is that, in spite of the eccentricity of the Warners publicist — who clearly valued his own satisfaction in this matter over the curiosity of my 330,000 or so readers — it really isn’t so aberrant after all. From my own experience both as a critic and as an occasional observer of the film industry, I would say that this industry operates to a surprising degree on just such arbitrary peccadilloes and demonstrations of personal power, exercised more for their own sake on many occasions than for the sake of any higher principles — including even business principles. The rise and fall of many reputations within this scheme — and I’m thinking now of people like stars and directors rather than publicists or critics — often seem determined by these ferocious yet arbitrary hobbyhorses, which carry the force of law once they’re extended beyond studios and their publicity machines and into the critical discourse itself. The spectacle of seeing these matters helping to determine in many cases what the rest of the country thinks about various movies and people is both comical and monstrous, but, I would venture to say, it happens on some level or another in the world of movies every day of the week, simply because the film industry itself — which, practically speaking, includes the press — is an organism largely made up of thwarted bureaucrats who dream of exercising some kind of power any way they possibly can, regardless of its ultimate meaning or consequences. Whether the final decision is that of a producer, director, distributor, publicist, exhibitor, or journalist-reviewer, the degree to which irrational impulses ultimately hold sway in certain matters should never be underestimated.

***

An issue somewhat related to the matter of interviews with directors is the question of whether a critic can or should write about the work of his own friends — and, to broach a related question, whether a film critic should allow himself or herself to become friends with filmmakers in general. Some of my more serious colleagues have studiously endeavored (with mixed results) to avoid such friendships and the potential conflicts of interest they could give rise to. In my own case, I happen to be friends with a good many filmmakers that I (usually) support, although most of these — such as Sara Driver, Sam Fuller, Jon Jost, Mark Rappaport, Râúl Ruiz, Peter Thompson, and Leslie Thornton — are filmmakers I initially supported before I ever became friends with them. (For the record, the only piece in this book written after I became friends with the filmmaker in question is the one on Fuller’s WHITE DOG.) One of my best friends, however, is an English experimental filmmaker, Peter Gidal, whose films I’ve rarely supported in print and have even on occasion attacked, although I find some of his theoretical positions interesting even when I disagree with them. Relatively early in my career, I nearly lost one friend, Eduardo de Gregorio, because of my failure to write about his first feature, SÉRAIL, when it showed at the Edinburgh Film Festival. Since then, I’ve generally been luckier and more successful in negotiating such matters, which are seldom easy.

***

My review of MÉLO represented something of a test case for me at the Reader because it ran to eighteen typed pages in manuscript. Michael Lenehan, the editor, responded that many readers probably wouldn’t get to the end of this piece and that I shouldn’t make a habit of writing reviews this long; but he generously agreed to run it without cuts. I don’t know in fact how many readers got to the end of the review, but I was gratified to discover that MÉLO wound up having a longer and more successful run in Chicago than it did in New York or Los Angeles. Much of this was undoubtedly due to Dave Kehr’s highly favorable review in the Chicago Tribune, but I’d like to imagine that my piece played some small role in this process as well.

Since I’ve been at the Reader, I’ve had nine different editors at one point or another. (The choice of who edits me each week usually depends on the amount of other work she or he has at the time.) After I turn in each column, I’m shown the editor’s major changes and queries and allowed to respond to them — a process of negotiation that always involves contesting certain changes, accepting others, and arriving at mutual solutions or compromises in still other cases. As I’ve discovered in my own endeavors in editing the prose of Truffaut, Welles, and Bogdanovich, the best editing is usually the kind the reader is least aware of, though the supreme masters of this game — who within my experience are probably Penelope Houston and Michael Lenehan — sometimes manage to minimize the awareness of the writer as well. (Conversely, the worst editors are those who render one’s prose unrecognizable; one of these effectively kept me from writing for Film Comment for years.)