From American Film (May 1979) –- a collaborative venture with Carrie Rickey, written during the year when we were flat mates living on Soho’s Sullivan Street. I assume that its main interest now is as a sort of time capsule, and I apologize if some of the photos are anachronistic, which seems likely. -– J.R.

With Broadway theaters threatening to raise their top prices to thirty-five dollars a seat, the place where most natives of New York City go is to the movies. Not, by and large, to the ritzy East Side movie houses which charge five dollars a head, but to the neighborhood cinemas charging half as much — many of them featuring movies hard to find outside of Manhattan.

A filmgoer visiting the city who plans to see the same movies he can find anywhere else can expect a long line and the hurried ambience of a fast-food restaurant. But if he’s determined to sample fare that’s more adventurous and unusual, he should seek out one of the independent showcases that have sprung up in New York over the past decade.

Here, more often than not, he can talk to the filmmaker after the screening and share the movie with a community of regulars. In contrast to the standardized conditions of mainstream filmgoing, the visitor can taste the regional and ethnic flavors, the eclectic styles and recipes of authentic home cooking. And excursions to these movie houses are like forays to off-Broadway theaters. One discovers different neighborhoods and a different cinema in the process.

The proliferation of these theaters parallels the various migrations of the artist population in lower Manhattan. Exotic new acronyms like SoHo, NoHo, and Tribeca have arisen to identify former cast-iron wildernesses and deserted factory wastelands-like townships named by the early pioneers.

At the independent theaters in these neighborhoods, one is likelier to find special-interest books and magazines, and notices of future events, than popcorn or soda. Instead of velvet curtains and slide-back seats, a spartan aesthetic (of necessity) informs the decor. yet the atmosphere is far from impersonal. The managers of these establishments are always vocal and visible, in contrast to the aloof presences that rule the commercial houses.

For the adventurous, we’ve suggested a week of unusual filmgoing in Manhattan, though we weren’t able to include all the possibilities Manhattan has to offer. But because these groups are mutually supportive — eschewing the competitiveness of the movie palaces — any one of these places will eventually lead to most of the others.

SUNDAY

To start off the week, a trip to Tribeca — an acronym referring to”triangle below Canal,” whose three sides are Canal Street, Broadway, and the Hudson River — will lead to the Collective for Living Cinema on White Street. Probably the most pluralistic of the showcases described here, this ambitious little organization has been in operation since 1973.

Launched by a group of film students at Harpur College (at the State University of New York at Binghamton) — where Hollywood veteran Nicholas Ray and experimental filmmaker Ken Jacobs were both teaching at the time — the Collective started to screen films at a couple of uptown churches. It had to use a collapsible projection booth at the locations in order to share space with other activities. Then, in 1971 it found a permanent location in a storefront on White Street – formerly a plastic tablecloth factory and a porn film studio — which was drastically overhauled in order to serve its current multiple functions.

From Monday to Thursday the Collective holds filmmaking workshops. Over the weekend it turns into a cinematheque that characteristically might offer on successive nights a neglected Hollywood thriller, a new avant-garde feature (with the filmmaker in attendance), and a European political film. It also produces an occasional intermedia periodical, No Rose, devoted to the avant-garde.

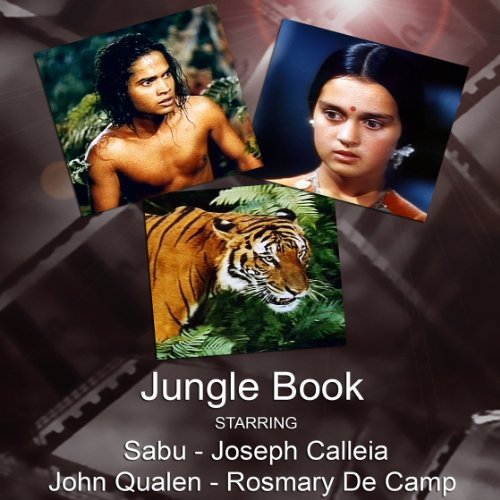

All of the programming is handled by twenty-five-year-old Renée Shafransky, who follows the refreshing principle that all kinds of films are relevant and interesting. Consequently, she comes up with offbeat choices that most showcases wouldn’t dream of. Some recent examples include films made for black ghetto audiences in the twenties and thirties by Oscar Micheaux, a black producer-director whose unorthodox techniques anticipate certain avant-garde strategies of Godard and Warhol; the New york premiere of Bruce Conner’s hilarious short Mongoloid, with music by the punk rock group Devo; George Kuchar’s feature Symphony of a Sinner; Humberto Solas’s celebrated three-part Cuban feature Lucia; a program of Yiddish films by cult director Edgar G. Ulmer, the latest diary film of Jonas Mekas; the 1942 version of The Jungle Book with Sabu; and John Water’s Mondo Trasho, described as a “’gutter film’ made in alleys, gutters, laundromats, dumps, and deserted areas around Baltimore.” [2013 correction: The photo below is from Multiple Maniacs.]

Supported by grants from the National Endowment for the Arts and the New York State Council on the Arts, the Collective caters to a friendly enclave of filmmakers and cinephiles as well as to more casual visitors. Most of its recent programs have been drawing capacity crowds.

MONDAY

In contrast to the recent success of the Collective, the Monday series at the Museum of Modern Art, called *Cineprobe,” has been in operation for over a decade. According to coprogrammers Adrienne Mancia and Larry Kardish, “Cineprobe” began with the express purpose of maklng independent films more accessible to audiences by introducing them to the filmmakers — a procedure that is often taken for granted today but was much less common when “Cineprobe” started in 1968. The rostrum of more than 160 filmmakers who have been invited to participate is indeed an impressive one. It ranges from “local” talents like Susan Sontag, Kenneth Anger, Melvin Van Peebles, and Ralph Bakshi to overseas visitors like Jean Eustache, Lindsay Anderson, Ousmane, Sembène, and Marco Ferreri.

Part of the idea animating “Cineprobe” is that once spectators engage in a dialogue with filmmakers, the films themselves become more understandable. Funded in past years by Exxon and Warner Communications, and more recently by the Jerome Foundation, this pioneering showcase has also been acquiring prints of films for the permanent collection of the museum’ s archives. Most of these have been American films, but Mancia and Kardish are hoping that future funding will permit more international acquisitions.

TUESDAY

The Whitney Museum of American Art is the best bet on Tuesdays, because every Tuesday between 6 P.M. and 9 P.M. admission is free. This means the events in the “New American Filmmakers Series,” as well as those in the museum’s exhibition schedule, are there for anyone’s delectation. The Whitney’s film and video program has an annual attendance of more than 50,000 because its audience is one of museumgoers as well as filmgoers. Museum guidelines limit film and video offerings to those that are American made, but this in no way hampers the creative programming of John Hanhardt and Mark Segal, respectively curator and assistant curator of the Film and Video Department.

Established in 1970 by David Bienstock, the “New American Filmmakers Series” is unique among independent showcases for three reasons: Films show continually for a minimum of a week, unlike the shorter runs at the other independent theaters; the program’s flexibility affords the opportunity for video artists and filmmakers to set up unorthodox viewing situations — Suzan Pitt’ s animated movie Asparagus was screened on an elaborately constructed miniature proscenium; Ira Schneider’s Manhattan Is an Island” was an installation of twenty-one television monitors, each broadcasting a different aspect of Manhattan — and Hanhardt and Segal select from work submitted to them from all over the country.

The Whitney’s program is varied, with equal parts of film and video. One week will feature a retrospective of pioneer animator Winsor McCay, the creator of Little Nemo. Another week will bring a videotape portrait of a contemporary composer, Robert Ashley’s ” Music With Roots in the Aether.” Yet another week holds Jon Jost’s feature Angel City, about a gumshoe’s meditations on free enterprise. The element common to the works in Hanhardt and Segal’s programs is that all are made outside the mainstream of commercial film and broadcast television production.

In addition to its screening schedule, the Film and Video Department organizes special exhibitions for the museum that detail the expanding concerns of film and video. This spring “Revisions: Projects and Proposals in Film and Video” is on view, featuring special installations by video artists and filmmakers which use the exhibition space itself as the content and context of the show. In the past the Whitney has sponsored a lecture series with such notable historians and critics as Annette Michelson and David Antin, and there are plans for more lectures.

Unlike the Museum of Modern Art, where departments of art and film are politely segregated, the Whitney has integrated film and video into the schedule of the whole enterprise. This makes the persuasive argument that all movies — be they avant-garde, feature, documentary, short subject, or animation — are ensured a firm position in American art.

WEDNESDAY

Six years ago Sidney Geffen, a former real estate consultant to motion picture exhibitors, took over the Carnegie Hall Cinema, a first-run art house, and made several strikingchanges in its appearance as well as in its programming. In the basement lobby he had an imitation of a Parisian café, constructed, and in the auditorium next door he began showing “classic repertory’ double bills. A year later, when he took over the Bleecker Street Cinema– a couple of blocks south of Washington Square and New York University — he instituted similar changes, with a bookstore instead of a café.

The bookstore (unlike the café) no longer exists, because it is being pooled into an ambitious film research center that is currently being charted by former Carnegie programmer Penny Yates. And, over the past few years, Geffen has also been publishing a film magazine, Thousand Eyes, and supplementing his repertory with a wide variety of special film events and seasons.

Anyone who has ever worked for Geffen (including both of us, as guestprogrammers) knows that almost everything happening these days around his theaters is in a state of perpetual flux: plans, projects, policies (including the magazine’s format), as well as personnel. This is due in part to Geffen’s ambitious brainchild Public Cinema (not to be confused with the Public Theater), an organization which recently acquired its nonprofit status and is sponsoring the research center cited above.

At present the Carnegie is being programmed by critic Martin Rubin and the Bleecker by French filmmaker Jackie Raynal, Geffen’s wife. Some specja] programs offered lately include “Cahiers Week” (a series of screenings and discussions planned by Cahiers du Cinéma), Hitchcock’s English films, recent undistributed films from France and Germany, and a weekly series of classic twenties movies. Our own contributions were “Sound Thinking,” devoted to the use of sound in films, and “Rivette in Context,” the seven features of Jacques Rivette and twenty other films that serve as critical or theoretical reference points to his movies and criticism.

In everyday operations, both the Bleecker and the Carnegie can be said to stand precisely in between the commercial theaters and the avant-garde showcases. A certain rough- and-ready atmosphere at both places keeps them lively and unpredictable, whether they’re catering more to music enthusiasts uptown (through proximity to Carnegie Hall) or to college students downtown (through proximity to NewYork University.

THURSDAY

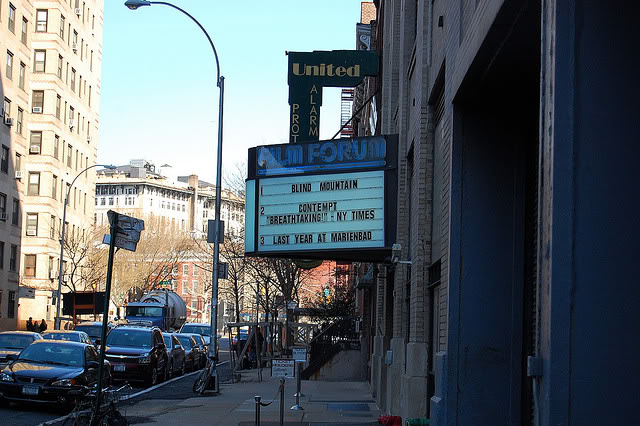

On the border of Greenwich Village and SoHo, Manhattan neighborhoods which bustle with writers and artists, is Film Forum. Situated in a residential area where James Agee made his home, Film Forum’s two-hundred-seat auditorium attracts many locals, but also numbers among its regulars those from far-flung areas. The lure? Director Karen Cooper claims she has no aesthetic ax to grind and chooses movies to which she has a strong response. Cooper’s entrepreneurial ax to grind is that she only shows movies which she can claim as New York premieres.

Screenings at Film Forum are Thursday through Sunday, admission is $2 .75, but members – who join for $5 — get in at the reduced rate of $I and are the first to see such exciting films as The Battle of Chile, Martin Scorsese’s ltalianamerican, and Kenji Mizoguchi’s l953 film A Geisha. Cooper’ s indefatigable public relations have earned her the best press coverage of any independent showcase in New York, and consequently, the audience at Film Forum has a broad demography.

As with most independents, Cooper’s receipts cover only part of the operating expenses. To make up the deficit, grants from the Ford Foundation, New York City Department of Cultural Affairs, National Endowment for the Arts, New York State Council on the Arts, Jerome Foundation, and Peg Santvoord have been essential. These public and private agencies are committed to the support of independently made film and creative programming and have been the consistent benefactors of enterprises like Film Forum.

Film Forum started in l970, and Cooper became its director in l972, when the operation was “fifty folding chairs in a space on West Eighty-eighth Street. ” Although today’s space on Vandam Street is cramped and poorly ventilated, Film Forum’s progress is irrefutable. Cooper sees her programming philosophy as two-fold: She serves the filmmaker by writing the program notes on each film she screens and by getting critics to report on the movies; she serves the public by being there first, seeking out hard.to-find items and bringing them to Manhattan.

Film Forum’s programs include documentaries, features, ethnographic studies, and animation; the audience for each of these genres is likely to return to see other types of work. The broad cross section of Film Forum’s audience attends movies that were formerly classified as “underground” or ”art” films. Film Forum brings these movies above-ground and takes them out of the institutional setting.

FRIDAY

Now that it’s another weekend, the visiting filmgoer has more reason than ever to shun the impossible lines at the midtown cinemas and to go down to Joseph Papp’s Public Theater, on Lafayette Street just below Cooper Square, where the Little Theater will be screening some relatively hard-to-see item that hasn’t yet got the exposure it deserves: Peter Brook’s 1953 film of The Beggar’s Opera; Robert Altman’s Thieves Like Us; Thom Andersen’s fascinating documentary Eadweard Muybridge, Zoopraxographer; a complete version of Sergio Leone’s Once Upon a Time in the West; or Nelson Pereira Dos Santos’s wonderful ethnographic comedy about cannibalism and colonialism, How Tasty Was My Little Frenchman.

Of the seven showcases featured here, the Little Theater is the baby of the family. It came into being about a year ago, when Andy Holtzman suggested the idea to Joseph Papp and then enlisted Fabiano Canosa to collaborate on the programming. They removed the shutters which flanked the ninety-odd seats in the cozy screening room designed by Peter Kubelka for Anthology Film Archives (see above photo) — before the latter shifted its location to Wooster Street — and acquired new 16mm and 35mm projectors before embarking on a series of revivals and retrospectives which have been drawing respectable crowds ever since.

Canosa — an energetic and cheerful Brazilian who received an award for Innovative Film Programming from the New York Film Critics five years ago for his ambitious work at the FirstAvenue Screening Room — is a strong believer in exposing New Yorkers to more international fare than they’re accustomed to getting. Supported by the François de Menil Foundation for the Arts, the Little Theater is currently planning an interesting array of retrospectives in addition to special revivals: Jean Cocteau, Krzysztof Zanussi, Harold Lloyd, Dusan Makavejev, Mike Nichols and Elaine May, and Shakespeare on Film, among others.

SATURDAY

The visitor has a choice. He can see a new avant-garde film and meet the filmmaker at Millennium in the East Village,a weekly showcase programmed by Howard Guttenplan, whose operations and film choices are similar to those at the Collective. Like the Collective, Millennium operates a film workshop and publishes a magazine. Or the visitor can try the Anthology Film Archives, which has a special spring program, “Autobiographical/Diaristic Experience in Cinema.” In the fall, during Anthology’s regular cycle, there are three hundred films, ranging from Robert Flaherty’s Nanook of the North to Michael Snow’s The Central Region.

In 1974 Anthology moved to its present location on Wooster Street in SoHo, a cozy residence amid artists’ lofts, galleries, and the proliferating boutiques and restaurants that inevitably presage a tourist region. Closed temporarily in the fall of 1978 because of its failure to comply with building codes, the future location and future direction of Anthology is now being decided by co-directors Jonas Mekas and P. Adams Sitney.

Anthology Film Archives’ activities are many. It is an archive that preserves and maintains rare films; it offers library, viewing, and other resources to students and scholars, and it provides public screenings of films its selection committee has designated as “essential”. If Anthology has come under attack for its partisanship of the three hundred movies in its collection, this is in part because the efforts of its directors have been so thorough as to have practically made Anthology’s history of the independent film the most readily accessible.

How did Mekas and Sitney accomplish this? Anthology has published three books, widely distributed, which focus on films in its repertory. This repertory, screened regularly over the last nine years, has educated a generation of film students in Anthology’s history of film.

Mekas is the first to admit that Anthology’s focus is narrow, and he hopes the program will expand from its present concentration on the avant-garde wing of the independent film movement to include other aspects . ” Despite the fact that New York has seven independent showcases, the screening situation is still primitive, ” he says. Mekas hopes Anthology will move to an abandoned courthouse on nearby Second Avenue, and, should this materialize, he anticipates a situation where there will be two screening rooms, regular seminars, and more space for preservation and library activities.

“We are classicists,” Mekas says proudly, and it is the shared belief in a classic canon of films that is the reason behind Anthology’s longevity and determination. But one person’s classicism, is another’s eclecticism, and, like the other showcases listed here, Anthology has a range of selections that is more exciting for its pluralism than for its purity. From Chaplin to Dreyer to Eisenstein to Brakhage, its definition of cinema is as broad historically as it is geographically.