My 1973 Cannes coverage for London’s Time Out (which ran in their June 8-14 issue, about a year before I moved to London from Paris), slightly tweaked. I’m pretty sure I submitted something longer and more detailed (judging from my penultimate sentence, my account of Jerry Schatzberg’s Scarecrow must have been one of the several things that was cut), but I no longer have the original version to verify this. — J.R.

May 11: Discounting Godspell, the opening film, which I avoided seeing yesterday both for its sake and for mine, the festival got off to a rousing start today with two strong and absorbing films.

Joseph Losey’s A Doll’s House -– shown in the official festival, out of competition — cannot however be considered a successful embodiment of the Ibsen play. The authorial agendas of Ibsen, Losey, and [Jane] Fonda ultimately diverge more than combine, and we arrive at an abrupt impasse – a torso of the play that’s still missing a head.

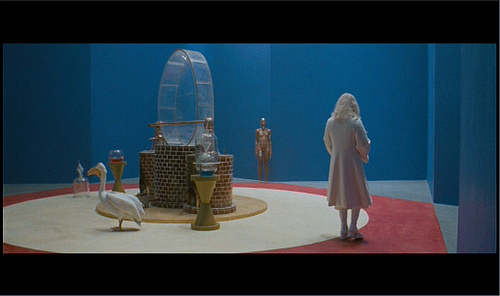

‘To waken the sleeping beauty,’ says a carnival barker in James B. Harris’s Some Call it Loving, which opened the Directors’ Fortnight, ‘you run the risk of being awakened yourself.’ This is the theme around which Harris spins a series of elegant and fluid variations, in a hypnotic film that haunted me throughout the festival, provoked me into seeing it a second time, elated me with its audacity and poetry, and drew from most of my colleagues a virtual barrage of contemptuous dismissals. Too bad for them.

Some Call it Loving is far from perfect, but it is hard to think of another contemporary American film that is both as romantic and as tough-minded about the processes and consequences of dreaming, nor anything else at the festival that relates to the Hollywood tradition is quite as original and distinctive a manner.

Much of Harris’s style derives from his decision to treat erotic obsessions musically, distancing the eroticism into a kind of hallucinated reverie that establishes some very private rules of its own. A young, white jazz musician (Zalman King) lives in a mansion with two women (Carol White, Victoria Anderson) who act out his erotic fantasies; his only friend is a black bum who hangs around the nightclub where he works (Richard Pryor, in a cartoonish performance suggesting a drugged-out Stepin Fetchit) and worships him –- another improbable form of wish fulfillment.

Purchasing a real Sleeping Beauty (Tisa Farrow) at a carnival, he brings her back to the mansion and waits for her to wake up; when she does, he finds her the willing embodiment of all his high-school dreams, a veritable prom queen. But it is this wish-fulfillment that defeats him: discovering that he is unable to cope with her actual (as opposed to potential) existence, he puts her back to sleep and returns her to the carnival, where, like his predecessor, he sells kisses to the men who want to try to waken her for the price of a dollar.

For anyone open to its singular moods and rhythms, Some Call it Loving offers a beautiful and disturbing experience.

May 12: Since nearly all the critics who despise Some Call it Loving went into ecstasies over James Guercio’s Electra Glide in Blue, I’ll leave it to them to sing its praises. Admittedly, there’s some impressive widescreen camerawork by Conrad Hall, who shot Fat City, and a fair amount if stereo rock to dress up the visuals, but essentially this a film for those who like seeing what they’ve already seen before, with slicker production values: a nice performance by Robert Blake as a sweet cop, who is shown putting on his gear in a sequence filched from Scorpio Rising, and is shot down by a hippy in a reversal of the ending of Easy Rider. There’s also an obligatory motorcycle chase with gory deaths in slow motion that provoked spontaneous applause in the Grande Salle.

Feeling sorry for Orson Welles having to recite the Sunday supplement commentary of Future Shock, a documentary screened in the afternoon, I left it to check out Confessor, an American underground effort by Edward Bergman and Alan Soffin shown in the Film Market. Despite some portentous attempts at structure, this is closer to a collection of shorts than a feature, and often amateurish shorts at that, pivoted around the general theme of media overload (another version of Future Shock?)

May 13: As far as I can tell, the only interesting thing about Alan Bridges’ The Hireling are that it (1) takes up one of the rustiest plots in the English repertory — poor chauffeur falls in love with ritzy lady — and makes it watchable; (2) changes its viewpoint midway from that of the latter to that of the former; and (3) contains some of Sarah Miles’s best acting. As for the fact that the film wound up winning half of the Grand Prix at the festival’s close, the most charitable explanation would be that at least half of the jury hasn’t been going to the movies in the past fifteen years….

May 14: Truffaut’s La Nuit Américaine (‘Day for Night’ — a technical movie term) is at least as slick as Electra Glide in Blue and The Hireling, but it also happens to be the most entertaining thing he’s done in years, combining the gentle charm of Stolen Kisses with some of the more pedagogical, instructional aspects of L’Enfant Sauvage.

The subject, a natural for Truffaut, is the shooting of a film; to make it even more personal, Truffaut plays the director himself and assigns the leading part — of the film and the film-being-made — to Jean-Pierre Léaud. Unlike 8 1/2, the focus here is less on the director than on the various subplots animating and counterpointing the work of the cast and crew, and the balancing of all these elements with the day-to-day mechanics of studio shooting is never less than masterful. For sheer craftsmanship this is a delight to watch; for all its inside dope (i.e., Léaud playing Léaud) and varied cinematic lore it should keep the film magazines busy for months.

But once again, at least for this jaded sensibility, the outstanding film of the day is another authentic weirdie — a Brazilian foray into science fiction by Nelson Pereira dos Santos called Who is Beta? and subtitled No Violence Between Us. This is the third Periera dos Santos film I’ve seen, after The Alienist and How Tasty Was My Little Frenchman, and on the basis of all three, I’m now inclined to regard his works as being everything that Glauber Rocha’s are reputed to be, and more. Madness in the first of these films, nudity and cannibalism in the second, and mass murder in the third are treated with an anthropological detachment , neither emphasized or de-emphasized but turned into commonplaces that form a neutral background. This moral suspension, always tinged with a very quiet sense of comedy and a vibrant passion for colour and action, performs the difficult feat of making the extraordinary seem ordinary.

Sometimes after a holocaust of some sort, apparently nuclear, humanity becomes split between the Contaminated (the majority) and the Non-Contaminated; the former depend on the latter for food, but at the same time the latter spend most of their time shooting the former, who offer no resistance. The Non-Contaminated hero (Frederic de Pasquale) lives in a beautiful shelter with an American girl and, later, also a Brazilian girl named Beta; when they three of them aren’t cheerfully killing the approaching hordes, they amuse themselves with a memory machine built by the hero which casts movie images of their pasts into a screen of smoke.

What can be said about such a bizarre, suggestive work, with allegorical overtones about the political power of sound and image, the past and present and future of Brazilian society, fertility myths, the cool murders committed by the privileged classes, the options of a tribal counter-culture, the dreams and habits of the bourgeoisie? All this and more is evoked in a story with many of the pure excitements of an action film, in which even the most inscrutable details are made to seem like the most natural phenomena. (Towards the end of the film, a tiny transistor radio is eaten by the hero and his companions when they can’t find any other way of keeping it quiet; meanwhile dozens of the Contaminated peer at them adoringly through all the windows and doors of the shelter.)

May 15: Much like musical comedies, hard-core porn films can largely be charaterized by the relationship between ‘plot’ and ‘numbers’. In this respect, Behind the Green Door, a somewhat silly if entertaining American orgy film directed by James and Artie Mitchell and shown in the Film Market, bears a certain affinity to the Busby Berkeley musical, Dames: that is, a long, unbroken stretch of plot is broken by a long, unbroken and plotless stretch of fucking.

After all the possibilities of building up suspense (what’s behind the green door?) are exhausted, the sex comes on, and after the directors (or actors?) apparently exhaust all the multiple couplings and variations that they can muster, the film suddenly turns arty, with ejaculations shown in extreme slow motion and a variety of colours.

May 16: As far as the official festival screenings are concerned, Jean Eustache’s The Mother and the Whore, later awarded a Special Jury Prize, is the first major event: three and a half hours devoted to the lives of three fairly drab inhabitants of St.-Germain-des-Prés — portrayed by Jean-Pierre Léaud, Bernadette Lafont, and Françoise Lebrun — and although most of this time is traversed before any sort of catharsis is reached, I didn’t find myself squirming at all; or hardly, anyway.

Some members of the audience booed the film’s direct handling of sex, but in fact this explicitness is present mainly in the dialogue, as in a scene involving a misplaced Tampax and the repeated use of the word “fucking” in an extraordinary soliloquy by Lebrun near the end, where she affirms, in an explosive tirade, that “There are no whores.” There is nothing avant-garde about Eustache’s methods, merely a passionate involvement in the lives of some rather conventional people that makes their problems our own, provoking an intimacy and interest that persists long after the film is over.

Two films at the Fortnight: Daryl Duke’s Payday follows the last couple of days in the life of a hard-living country music singer, intelligently played by Rip Torn — a familiar story sparked by some knowing details about the milieu he inhabits. For its first five minutes and its closing ten, Werner Herzog’s Aguirre, The Wrath of God, which concerns a 16th century expedition of Spanish conquistadores in Peru, is absolutely awesome in its visual splendours and surreal inventions (a long trek down a mountain; a ship perched high in the branches of a tree; a magical appearance of chattering monkeys); the remainder is horribly sabotaged by the American-English dubbing — an anachronistic monstrosity evoking some awful Richard Egan epic like Seven Cities of Gold — and a stilted and mannered performance by Klaus Kinski. In his press conference, Herzog seriously contended that he’d originally wanted the president of Algeria to play the Kinski role, and revealed that the ‘historical chronicle’ quoted during the film was his own invention.

May 18: Inexplicably, Alexandro Jodorowsky 4-million-dollar pseudo-mystical circus, The Holy Mountain, a fiction film if there ever was one, was shown in the afternoon documentary series. A simultaneous attempt to do Hellzapoppin and The Greatest Story Ever Told, served up by the man who made El Topo (still unreleased in England) and who in his more modest moments compares himself to Christ and Buddha, this outrageous spectacle is admittedly full of some very striking moments: an old man taking out his eye in closeup to give to a girl, a legion of lizards dressed in armour, crowds being machine-gunned and spouting blood of various colours (blue, yellow, etc.)

Although Jodorowsky claims to have made this film for the greater good of not only Alan Klein (the producer) but all of humanity, he might have better served the interests of the latter by shoveling all 4 million out of the nearest available window. Nevertheless, despite his lack of any organizational control, he manages to splatter is 70mm canvas and stereo soundtrack with plenty of shocks and startling images to keep one alert. If only he’d stick to Hellzapoppin and forget the borrowed mysticism, he might turn into a genuinely important director: at the very least, the Ken Russell of the occult circuits.

May 19: Long live Samuel Fuller! His Dead Pigeon on Beethoven Street, finally surfacing on the Film Market, is riddled with faults, but here for once is the work of a man who loves making movies, and proves it by bringing a fresh idea to practically every scene.

May 20: Bill Gunn’s Ganja and Hess in the Critics’ Week is an impenetrable but fascinating curiosity — often dull but never predictable, technically uncertain yet wholly distinctive. It also represents something of a historical precedent in that it was produced, written, directed and acted by American blacks and makes no commercial concessions of any kind. Gunn introduced the film by saying, ‘We’re not yet allowed to make personal films — so I was offered a vampire movie to do instead. When they came back, this is what they found.’ Verbose and theatrical in spots, not even remotely Gothic or scary, Gunn’s film relates vampirism both to black religion and to an African past, dealing with a black aristocrat, played poker-faced by Duane Jones, who ‘lives in a world of dead objects left by a civilisation that isn’t his own.’

Visions of Eight in the afternoon documentary series — eight directors filming parts of the Olympic Games in Munich — is a very uneven and mainly derivative hodgepodge, none of which comes within hailing distance of Leni Riefenstahl’s subline 1936 version.

May 21: Philippe Mora’s Swastika — again, in the documentary series — includes a great deal of what is generally omitted in other accounts of the Nazi regime: a view of Nazis as ordinary people. This view is chiefly conveyed by recently discovered home movies shot by Hitler’s mistress, Eva Braun, which show Hitler and his cohorts in a light that makes them look like relatives at a friend’s wedding. As part of the total picture of Nazism, this is a necessary dimension, as Hannah Arendt has already persuasively demonstrated in Eichmann in Jerusalem. regrettably, Mora doesn’t appear to have known how to work this and other footage into an interesting or meaningful structure; he even damages the validity and relevance of the home movies by dubbing in voices for each of the characters — creating a historical travesty that cannot be excused by the fact that most (if not all) of the dubbed lines are based on lip-reading.

May 22: Carmelo Bene’s One Hamlet Less begins with some striking visual ideas — pure white backdrops, outlandishly overblown and opulent costumes — and then proceeds to repeat these motifs ad infinitum, to the point of monotony and beyond.

May 23: Undoubtedly the most important film that I’ve seen at Cannes this year, and perhaps the only incontestable masterpiece, is Teinosuke Kinugasa’s explosive A Page of Madness, a silent Japanese feature that has already been seen in London and discussed in these pages, and was viewed today by myself and less than a dozen others while, to judge from all the reports, thousands of unlucky spectators chose to suffer through Frankenheimer’s Impossible Object.

Paul Newman’s The Effect of Gamma Rays on Man-in-the-Moon Marigolds is a very professionally wrought example of kitchen sink realism: Joanne Woodward’s unglamorous role as an unhappy mother of two teenage daughters is so totally worked out and ‘finished’ that it probably deserves the burial implied by the festival prize for best actress awarded to her.

Late in the evening, the Cinémathèque Française holds a screening of the 1931 The Miracle Woman in homage to Frank Capra, who is around afterwards for questions. Asked whether he’s seen the new version of Lost Horizon, he replies: ‘No, and judging from what I’ve heard about it, I don’t think I will.’

May 24: Although Wojciech J. Has’s The Sandglass, shown today in competition, wound up receiving the Jury Prize, its reception in the Grande Salle was rather cool. Perhaps if it had been screened towards the beginning of the festival, when everyone had more mental and physical stamina to spare, it might have been acclaimed more generally as a masterpiece, surpassing even The Sargossa Manuscript in sheer style and invention. Based on a collection of short stories by Bruno Schulz –a remarkable writer who flourished between the two Wars, whose recognition in England and America is long overdue — Has’s fantasy of Jews in pre-war Poland reveals the imagination of a Fellini without the posturing and grandstanding. Passing through the beautifully lit, bluish haze of a sanitarium steeped in memories where, as a nurse remarks, ‘We sleep all the time and it’s never night,’ the hero takes a journey into his past that proceeds through a series of dream-like transitions, under tables and up ladders into a magical world of enchantment.

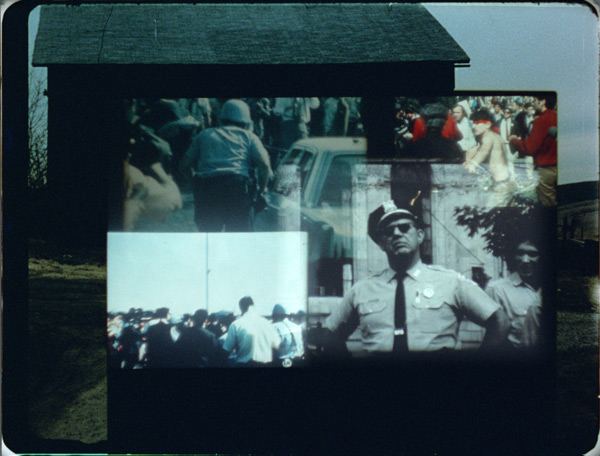

The final documentary and the last official event that I attended was Nicholas Ray’s We Can’t Go Home Again, a film made in collaboration with his filmmaking class at Harpur College at the State University of New York [at Binghamton]. The screening amounted to a partial disaster, not only because the lack of French subtitles and an unsuccessful (and fortunately discontinued) attempt to offer a simultaneous voiceover translation caused much of the audience to walk out, but also because, as Ray himself observed in his subsequent press conference, ‘I think we’ve got another month of work to do on this film.’ Perhaps even more problematical was the fact that We Can’t Go Home Again attempts the impossible, in what was surely the most radical step towards cinematic innovation to be found at Cannes: a combination of 35, 16 and super-8 footage, overlapping and set alongside one another, that combines fiction and documentary, with Ray himself and his students figuring as the central characters.

In addition to the incoherent sections are others of enormous force and power, where the theme of political alienation engendered by the Chicago and Miami presidential conventions in in 1968 and ’72 are combined with personal and confessional psychodrama to create some very potent statements. If this bothersome, unruly film reflects any truth about the Cannes Festival this year as a whole, this may be that for all the attempts at various kinds of classical perfection — from Losey to Guercio to Bridges to Truffaut to Schatzberg to Newman — it is the uncharted voyages into the unknown, by Harris, Pereira dos Santos, Gunn, Has and Ray, that carry the greatest promise for the future. Only rare masterpieces, like perhaps the Eustache and the Kinugasa, manage to straddle both possibilities.