The following article was partially written as a way of conserving space

while editing This Is Orson Welles (1991). A particular problem I had

throughout that project was having more material that I wanted to use

than I had room for. So I figured that if I could write and publish articles

elsewhere that incorporated portions of this material, all I had to do in the

book was allude to them.

Mr. Arkadin has always been the most difficult to research of the

Welles films that were finished in some form while he was alive —

partially because it remained such a painful memory to Welles due

to his friendship with Louis Dolivet, the producer, that he avoided

discussing it. Indeed, there was barely any material at all about it

in the tapes and drafts for This Is Orson Welles that I had

to work with. So as I tried to expand what I had via research,

I eventually hit upon the idea of publishing a piece in Film

Comment. (This appeared in January-February 1992.)

By necessity, much of what I included in this article was provisional.

(The same applies to a lesser extent to the dual commentary I

recorded with James Naremore in early 2005 to the film’s “Corinth

version” [no. 3 in the article] for a Criterion DVD box set

released in April 2006.) But I didn’t realize how provisional it was

until the Welles conference held at the Locarno film festival in August

2005, when French Welles scholar François Thomas, who had recently

examined the files of Dolivet, generously went to the trouble of making

out a list of all the errors in this piece that he was then aware of.

Since much more detailed and comprehensive accounts appeared in a

book on the production and postproduction histories of Welles’s films

that François wrote with Jean-Pierre Berthomé [Orson Welles

at Work], as well as a series of articles François wrote for the biannual

French journal Cinéma in 2006–2007, he asked me to omit a couple of

his findings here, but otherwise his list, most of it paraphrased in this

preface, is virtually complete: It’s now certain that Welles didn’t attend the

Paris premiere of Arkadin, and it’s certain that Louis Dolivet produced

other films afterwards, including Jacques Tati’s Mon oncle and Parade.

He also coproduced La dolce vita. There are at least two Spanish

versions of the film, not one (by now I’ve seen both), and the shot of a

dead woman’s body on a beach is the second in one of these, not the first.

Welles spent more than four months editing the film, and the “Christmas

1956 deadline” was only one among several. There is now documented

proof that Maurice Bessy wrote the novel. Amparo Rivelles and Irene

Lopez Heredia are the only two Spanish actors used specifically in the

Spanish versions, and it’s now certain that Welles directed both of them.

The bats seen behind the credits of Confidential Report can also

be glimpsed at the masked ball. The seventh Arkadin identified in

the article is actually a truncated version of no. 3, not a truncated

version of Confidential Report (no. 6), and one can further

argue that, apart from its chronological structure, no. 6 contains

more of Welles’s editing than no. 3. Furthermore, it appears that the

project’s postproduction history is far more complex than most

Welles scholars have assumed, and the process by which Welles

lost control over the film was partially a matter of his own initiatives,

motivated or at least inflected by his friendship with Dolivet.

On the issue of how critical scholarship and commercial

interests can sometimes come into conflict with one another,

the following anecdote may be somewhat instructive. When I wrote

liner notes for the Voyager laserdisc of Confidential Report

(no. 6) in the early 1990s, my assertion in those notes that

no. 6 was the second-best version of Mr. Arkadin was

censored. Roughly 15 years later, when I was commissioned

to write liner notes for what I’d previously thought to be the

best version (i.e., no. 3) for a DVD box set of Arkadin released

by Criterion, a company that grew out of Voyager — a version

that Thomas persuaded me may not have been the best after all,

at least in all particulars — I wasn’t censored about my preferences.

But it’s amusing to note that in the interests of both clarity and

symmetry with the two other versions of Arkadin included in the box

set and their respective liner notes, I was still asked to revise my notes

in order to make them more supportive.

Spanish film scholar Esteve Riambau has contributed much to our

knowledge of Welles’s work on this film (and others) in Spain, including

many of the precise locations, though lamentably this work has been

available mainly in Spanish or at Welles conferences, without wider

circulation (apart from the excellent documentary in 2000 he made

with cowriter Carlos F. Heredero and director Carlos Rodriguez,

Orson Welles en el país de Don Quijote — the only

treatment of Welles in Spain I’m familiar with that brings some

critical perspective to his willingness to live in Franco Spain and

part of what this entailed). And from German film scholar Hans

Schmid, who produced a German version of the Harry Lime radio series

in the 1990s (and who once took me on a tour of all the major Munich

locations used in Mr. Arkadin, during my first visit there — the most

startling of which is the building that houses Jakob Zouk’s attic, rehabbed

but still recognizable, and by pure coincidence located today across the

street from the Munich Film Archives) — I’ve learned much more about

what radio shows the film derived from. All of them survive in two versions,

some of which have separate titles, which has led to many confusions.

The principal source was the second version of “Man of Mystery,”

not “Greek Meets Greek,” and other elements in the film came from

“Murder on the Riviera” (called “Cigarettes” in its earlier version),

“Blackmail Is a Nasty Word” (called “Givrolet” in its previous version),

and, to a lesser extent, some others [Most of this Introduction comes

from my recent collection Discovering Orson Welles.] –- J.R.

The Seven ARKADINs

I wanted to make a work in the spirit of

Dickens, with characters so dense that they

appear as archetypes….I thought it could

have made a very popular film, a commercial

film that everyone would have liked. In place

of that…I’m afraid to see it! It’sterrible, what

they did to me on that. The film was snatched

from my hands more brutally than one has ever

snatched a film from anyone…it’s as if they’d

kidnapped my child! They brought in another

cutter who pretended to have “saved” the film!

-— Orson Welles in l’Avant-scène du cinéma, no.

291–292 (1–15 July 1982) (my translation)

It’s generally known that, for a variety of reasons, some of the films of Orson Welles survive today in two or more versions. James Naremore has told me he once saw a print of THE LADY FROM SHANGHAI in Germany that included alternate takes of certain scenes and somewhat different editing, plus a few shots he hadn’t seen before or since. (This sounds roughly comparable to the “Italian” version of Stroheim’s FOOLISH WIVES , apparently sent overseas before the domestic version was completed.) Better known are Welles’s two separate versions of MACBETH, running 107 minutes and 86 minutes. (The second was prepared after Welles was asked to cut two reels and redub the “Scots” dialogue; it contains offscreen narration missing from the long version but doesn’t contain the single take lasting an entire reel which preceded Hitchcock’s ROPE by a year.) Still better known are the two editions of TOUCH OF EVIL -— the 93-minute version originally released and the 108-minute version discovered in the mid-70s that has virtually supplanted it. Since Welles was barred from the final stages of editing, neither can be considered definitive; indeed, it’s impossible to speak of a definitive TOUCH OF EVIL.

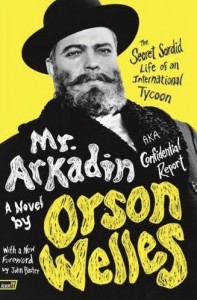

The same is true of MR. ARKADIN (1955). But in this case the consequences are much more confusing because of the number of ARKADINs we have to choose from—-plus the fact that the version best known in this country is very far from the best.

Here, in simplified form, is more or less how the story line goes.

In Naples, a man, Bracco (Grégoire Aslan), mysteriously knifed in the back, whispers two names while dying: “Gregory Arkadin” and “Sophie.” The only people to hear are Guy Van Stratten (Robert Arden), an American smuggler, and his girlfriend, Mily (Patricia Medina). Hoping to snare a fortune via blackmail with these names, Guy tracks the fabulously wealthy Arkadin (Welles) to a castle in Spain and, against the man’s wishes, woos his sheltered and beloved daughter Raina (Paola Mori). Unexpectedly, Arkadin, who claims to suffer from amnesia, hires Guy to prepare a confidential report on his activities prior to 1927. Guy conducts interviews all over Europe and in Mexico, basically tracking down former members of a gang of white slavers to which Arkadin belonged. These include Oskar (Frederick O’Brady) and Sophie (Katina Paxinou) in Mexico and Jakob Zouk (Akim Tamiroff) in Munich; Mily helps out by speaking with a black marketeer (Peter van Eyck) in Tangiers and with Arkadin himself on his yacht. As Guy uncovers Arkadin’s past, he gradually discovers that his employer, afraid Raina will learn who and what he oncewas, is having his old associates murdered, as well as Mily. Fearing for his own life, Guy flies to Raina in Barcelona ahead of Arkadin, who is following in a private plane. Guy convinces Raina to tell her father, over the plane’s radio, that she now knows everything, at which point Arkadin kills himself by leaping from the plane. Raina leaves Guy in disgust.

In 1958 the editorial board of Cahiers du cinéma collectively decided that MR. ARKADIN —-more precisely, CONFIDENTIAL REPORT, as they knew it —- was Welles’s greatest film, the one that belonged on their list of the twelve greatest films ever made. At the time, not long after the film’s appearance in Europe, there was no public awareness that Welles had lost editorial control over it; the director had lent his presence at the Paris premiere, and apparently made no public statements about his creative difficulties until some time later. Even now we have less information about the making and the editorial reworking of ARKADIN than we have about any of the other Wellesnarrative features released during his lifetime.

What we do have is a tantalizing panoply of texts—for the purposes of this discussion, seven-—in a variety of media. They range from the stylistically conventional to the stylistically radical, from the tossed-off tothe aesthetically intricate. The Cahiers editors’ odd preference notwithstanding, I don’t consider ARKADIN a masterpiece in any of its versions or incarnations. But I find most of it fascinating and much of it beautiful and exciting — “it” in this case being a conflation of ARKADINs nos. 3, 6, and 7 (in descending order of importance) among the exhibits I propose to submit for consideration.

What’s offered below isn’t so much a map of a “definitive” ARKADIN as an exploration of a few of the processes that the story and film went through. It is, if you will, a kind of detective story without a denouement, but with plenty of clues. The mode is tentative historical inquiry, selective and suggestive in intention rather than exhaustive, with a few critical remarks appended.

In pursuit of my own confidential report, I have greatly benefited from three invaluable sources in addition to the primary texts: an afternoon spent with a good many loose pieces of the producer’s workprint materials —- examined on a moviola with two other Welles scholars, Ciro Giorgini and Bernard Eisenschitz -— thanks to the exceptional generosity of Fred Junck and Marco Müller; a phone interview graciously granted me by Patricia Medina; and This Is Orson Welles by Orson Welles and Peter Bogdanovich, a book I have been editing for HarperCollins. I’d also like to thank Geoff Andrew, Tag Gallagher, James Pepper, Bill Reed, and Bret Wood for furnishing me with some of the primary materials.

***

Pre-Texts

1: “Greek Meets Greek” — half-hour episode of the London-based radio series The Adventures of Harry Lime, a spin-off of the Welles character in the 1949 Carol Reed/Graham Greene film THE THIRD MAN. Written by and starring Welles,directed by Tig Roe, and probably recorded in 1951, the segment is quite unremarkable except as the source for ARKADIN’s skeletalplot and key themes.

2: Masquerade -— early version of Welles’s script for ARKADIN, dated March 23, 1953, the year before shooting commenced. Masquerade differs from most or all of the later versions in the following ways:

(a) The opening quotation is not an aphorism about a king and a poet and a fatal secret, but a quotation from Emerson:

Commit a crime, and the earth is made of

glass. Commit a crime and it seems as if a

coat of snow fell on the ground, such as

reveals in the woods the track of every

partridge and fox and squirrel and mole.

You cannot recall the spoken word, you

cannot wipe out the foot-track, you cannot

draw up the ladder, so as to leave no inlet

or clew.

This also appears in the French and Italian editions of the novel, but apparently none of those in English. As Richard T. Jameson has pointed out to me, the same quotation is recited by Edward G. Robinson in Welles’s THE STRANGER (1946).

(b) Apart from the precredits sequence of the riderless plane — which exists in every version of the film but not the novel — there are no flashbacks and no offscreen narration. The plot progression is strictly chronological.

(c) The investigator is called “Guy Dumesnil” and is described as “young and attractive” and “an Americanized European” (notan American called Guy Van Stratten). The Jakob Zouk character (played by Akim Tamiroff in the film) is called “Jakob Nathansen.”

(d) Most of the major scenes in the script are in the film, although some are set in different countries. Arkadin’s masked ball is in Venice, not Spain (“This is clearly an attempt on Arkadin’s part to out-do the famous Bestigui Ball, and is infact, in many ways, a duplication of it. . . . The canals are filled with illuminated gondolas carrying Arkadin’s guests,all in costumes of the Venetian 18th century. . . .”). Similarly, the pawn and junk shop of Burgomil Trebitsch (Michael Redgrave)is located in Marseille, not Copenhagen. A few scenes in the film, such as the one featuring the flea circus director (Mischa Auer), are not in the script.

(e) Perhaps the most extended material available here but missing from all the other versions of ARKADIN (except for the novel, where it figures in a somewhat different form) involves Van Stratten’s adventures when he first arrives in Mexico, before he questions Oskar and Sophie. He attends the funeral of Sophie’s elderly toy poodle Ki-Ki,[*] and tracks down Oskar in a “kosher café” run by Sophie, where he plays the accordion for tips. Van Stratten lures Oskar onto a rented boat by offering him a high fee to entertain guests on an alleged pleasure cruise, at which point he begins to torturehim for information by depriving him of heroin. Only a brief version of this boat scene survives in the film.

(f) In the film, there is a confrontation between Van Stratten, Arkadin, and Raina in Guy’s hotel room in Paris; the script sets the scene in Van Stratten’s flat, and Arkadin appears only belatedly. (In the workprint, Welles conducts a rehearsal for part of this scene and, in instructing Mori how to deliver some of her lines, gives the setting as New York.)

***

Films and Filming:

“A Phenomenon of an Age of Dissolution and Chaos”

I was developing the rushes of ARKADIN

in a French lab. Can you imagine that I had

to have a special authorization for every

piece of film, even if only 20 yards long, that

arrived from Spain? The film had to go through

the hands of the customs officials, who wasted

their time (and ours) by stamping the beginning

and end of each and every roll of film or of

magnetic sound tape. The operation required two

whole days, and the film was in danger of being

spoiled by the hot weather we were then having.

The same difficulties cropped up when it

came to obtaining work permits. My film unit was

international: I had a French cameraman, an

Italian editor, an English sound engineer, an

Irish script girl, a Spanish assistant.

Whenever we had to travel anywhere, each of them

had to waste an unconscionable amount of time

getting special permissions to stay to work….

Similar complications arose when, for example,

we had to get a French camera into Spain….

The true culprits are the producers. They

prefer the security of a limited but certain

profit from a national or regionalmarket to

the infinitely wider possibilities of a world

market, which would of course entail, at the

outset, certain supplementaryexpenses.”

(Orson Welles, “For a Universal Cinema,” Film

Culture1. no. 1 [January 1955])

A few words about the making of MR. ARKADIN. Louis Dolivet, the French producer, who died not long ago, was a good friend and political mentor to Welles in the United States during the mid-40s. (See Barbara Leaming’s biography Orson Welles [New York: Viking Penguin, 1985], for particulars.) Dolivet never produced a feature prior to ARKADIN and, to the best of my knowledge, never produced another afterward. The little evidence we have suggests that ARKADIN’S production was an exacerbating experience for him and Welles alike and that their friendship ultimately proved to be one of its casualties. To make matters worse, Paola Mori -— the professional name of the Countess di Girfalco, who later became Welles’s third and last wife -— was criticized so harshly for her performance by Dolivet and others that she gave up acting, appearing again only in cameos in THE TRIALand the unfinished DON QUIXOTE. (Again, the workprint rehearsal footage is suggestive: Mori’s musically accented voice is distinct from the English-accented voice we hear in the released films, raising the possibility that “Raina” ‘s voice wassubsequently dubbed by another actress. [1].)

It appears that most of the film was shot in Spain — much of it in a studio in Madrid — with a certain amount in Munich and Paris locations and probably a few pickup shots elsewhere in Western Europe. (One can’t take seriously any of those accounts claiming that part of the shooting was done in Mexico.) On the basis of my interview with Patricia Medina and the slates visible in certain outtakes, we know that many scenes were shot, wholly or partially, in or near Madrid. These encompass such fictional settings as a hotel in Mexico City, the docks in Naples, Arkadin’s yacht, the interior and environs of his Spanish castle, a café in Tangiers, a nightclub on the Riviera, and the inside of a Munich cathedral!

Patricia Medina has never seen ARKADIN, so all her memories are tied exclusively to her own participation in the film. She was under contract to Columbia at the time, and when Welles phoned her in London to ask her to play Mily, she had very littletime to shoot because she was due back in the states to act in something else (probably MIAMI EXPOSÉ). Welles replied jokingly, “Then we’ll have to kill you off.” (Mily’s murder, alluded to offscreen in the film, was never shot in any form.) Medina flew to Madrid and all her scenes were shot there, most of them in a studio, over about ten days.

Overall, she remembers the shoot as a happy event. The first scene she did was on the yacht with Arkadin. The night before shooting, Welles showed her the set, asking scornfully, “Doesn’t it look just like the Staten Island Ferry?” The yacht set was up in the air; one had to climb up into it. After Medina returned to her hotel, Welles phoned to ask her if there was anything in her hotel that “belonged in a yacht.” She looked around and found very little. When she arrived for filming the next morning, she discovered that Welles had been up all night redressing the set with furniture temporarily swiped from the lobby of the Madrid Hilton, where he himself was staying. He announced that they had time for only two takes because the furniture had to be returned before it was missed. (One detail in this scene was improvised: when Mily says “Shut up!” to a screeching bird in a cage, neither the screech nor her line was in the script.)

Medina’s participation in the scene featuring the procession of penitentes near Arkadin’s castle was all done in a studio. Interestingly, although Paola Mori appears in the same sequence, Medina never met her during the shooting. If one examines this scene closely, it becomes clear that Mily and the procession never appear in the same shot; the illusion of proximity is supplied and intensified by the shadows -— ostensibly of the penitents —- flickering across Mily and Guy.

When she left for the States, Welles asked her to send a still of herself that could be blown up for a poster advertising Mily as a bubble dancer. She neglected to do so. When she arrived in Paris sometime later to do the dubbing with Welles, she was appalled by the still that he had found and used on his own. (When Van Stratten learns of Mily’s death later in the film, this picture recurs in some versions, identified in the dialogue as “the only available photo taken before death.”) And that marked the end of her involvement, save that much later she was contacted by Dolivet to act in some additional scenes; learning that Welles wouldn’t be directing them, she refused.

But back to The Seven ARKADINs. . .

***

3: MR. ARKADIN, the film — that is to say, the version of the film closest to Welles’s conception. This became available in the United States through Corinth Films; we owe the original existence of this version in the United States to Peter Bogdanovich,who discovered it in Hollywood in 1961, and to Dan Talbot of New Yorker Films, who acquired it for the belated U.S. premiere and release of ARKADIN the following year.

According to the film’s editor, Renzo Lucidi (recently interviewed by Ciro Giorgini), the first four sequences of this version correspond precisely to Welles’s intentions. It opens with Van Stratten visiting Jakob Zouk in Munich, then continues as a series of flashbacks narrated offscreen by Van Stratten, periodically returning to Zouk’s attic flat.Welles spent four months editing, averaging (according to Lucidi) two minutes of finished film per week. He was barred from the cutting after failing to meet Dolivet’s Christmas 1954 deadline, but continued to communicate his intentions to Lucidi. Once Lucidi had finished editing this version, however, Dolivet apparently asked for the film to be reedited without most of the flashbacks -— in chronological order after the opening sequence -— and this was the principal version released in Europe as CONFIDENTIAL REPORT. (See no. 6, below.)

In This Is Orson Welles, Welles maintains that at least two important scenes of his were eliminated from all the released versions of ARKADIN. This would seem to be corroborated by Frank Brady’s citation, in his Welles biography, of an undated New York Herald Tribune story in which Welles complained that fourteen minutes were removed from his version. To Bogdanovich, Welles cited another party scene and an additional scene between Arkadin and Van Stratten, both of which showed Arkadin “as a sentimental, rather maudlin Russian drunk”; Arkadin’s character, he added, was inspired to some extent by Stalin.

Given Welles’s relative unfamiliarity with the release versions of his film -— which he clearly found painful to watch -— these remarks may have alluded to further material in Arkadin’s masked ball, or at the Christmas party in Munich (where we do see Arkadin drunk).Alternately, they may refer to two complete scenes of which we no longer have any record in any of. Since Welles had a penchant for revising his scripts while shooting —- and even, on occasion, revising dialogue while postdubbing and editing—-both hypotheses are plausible.

Apparently one of the reasons why ARKADIN was so late -— seven years! —- in opening in the United States was a $780,000 legal suit filed by the European production company Filmorsa againstWelles in New York, claiming that Welles’s behavior was responsible for the film’s ultimate commercial failure. This action was launched on April 7, 1958, but papers weren’t filed until September 28, 1961; on the following day brief news stories were run in the New York papers, citing “drinking excessively on and off the set” as the principal charge. In the Times, Welles called the charges “blunderbuss, catch-all phraseology, naked generalizations, unsupported inferences and patent irrelevancies,” while one of his lawyers maintained that it was Filmorsa rather than Welles that had broken the contract. The charges, in any case, were eventually dropped.

4: Mr. Arkadin, the novel, signed by Welles but not written by him —- although the version available in English is an anonymous translation of a French novel ghostwritten by Maurice Bessy that was based, in turn, on a version of Welles’s film script, in English,that was written at some point after no. 2. The novel was originally composed for newspaper serialization in France, and first appeared in book form there at the time of CONFIDENTIAL REPORT’S French release.

The novel is divided into three sections, entitled “Bracco,” “Sophie,” and “The Ogre.” Narrated in the first person by Van Stratten, it most closely resembles no. 7 in its overall form. The most significant material missing from all other versions relates to Van Stratten’s mother, a professional gambler who, at the time of the novel, is occupying “a tiny two-room flat at Beausoleil with Myrtle,” an English gambling companion, and appears briefly, along with Myrtle, in the second chapter.

Although Lucidi has recently maintained that Welles wrote the novel, all the other available evidence -— including a conversationI had with Welles in 1972 -— refutes this. A comparison of the novel’s dialogue with the film’s suggests in virtually every case that the former is a retranslation back into English of French dialogue adapted from an English script; the meanings of linesare generally the same, but the words and phrasings are almost always different.

5: The Spanish version of the film. If the current “Spanish version” is identical to the one that opened in Madrid in March 1955, then this is probably the first version that premiered anywhere. I’ve been able to see only a few parts of this version -— presumably the most significant parts -— in Ciro Giorgini’s invaluable TUTTA LA VERITA’ SU MR. ARKADIN, a 1991 TV documentary for Italy’s RAI.

The Spanish version was apparently shot simultaneously with the principal production. It features different actresses playing the parts of Sophie and Baroness Nagel (and perhaps other Spanish actors as well), as part of the arrangement made for a Spanish coproduction. A different editor is also credited, Antonio Martinez. In the precredits sequence, the pilotless plane is said more vaguely to have been sighted somewhere in Europe rather than “off the coast of Barcelona”; in the glimpses of the actors shown in the credits, we see Amparo Rivelles instead of Suzanne Flon as the Baroness Nagel, Irene Lopez Heredia instead of Katina Paxinou as Sophie; Robert Arden is inexplicably identified as “Bob Harden.” As for the scenes involving Rivelles and Lopez Heredia, the first of these alternates shots of Welles (dubbed by someone else) with reverse angles of Rivelles in what appears to be a crude approximation of the same set (a fancy Paris restaurant); it seems highly unlikely that Welles directed these reverse angles. But in the scene with Lopez Heredia and “Harden,” the set appears to be the same one used in the English-speaking versions, and the lighting and mise en scène, while not quite identical, are sufficiently Wellesian to suggest that Welles himself might have directed this alternate version of the scene.[*]

6: CONFIDENTIAL REPORT -— the version of the film that opened in London in August 1955 and apparently the main version that was and is shown elsewhere in Europe, including France.

It seems quite possible that an early draft of Welles’s script was used as a guide in reediting this version, a detailed description of which is available in French in the issue of l’Avant-Scène du Cinéma cited at the beginning of this article. (This description includes annotations about materials found in the workprint). As Giorgini shows in his documentary through a split-screen technique, the differences between this version and no. 3 are more than just a matter of chronological sequence; they involve variations in editing and dialogue and/or narration within scenes,and in a few instances may even involve different takes.

There are at least two brief scenes in CONFIDENTIAL REPORT that are missing from both no. 3 and no. 7 -— a scene in which Van Stratten speaks to a black American pianist in a bar on the Riviera while looking for Mily and Arkadin’s “Georgian toast” near the end of his masked ball, in which he recounts a curious dream set in a cemetery. This also happens to be the only version containing shots of hanging papier-mâché sculptures representing bats in the opening credits sequence. (As to what they refer to in the film, they could be either objects in Trebitsch’s junk shop or part of the decor at Arkadin’s masked ball; when queried about these bats by Bogdanovich, Welles had no recollection of them.)

Another major difference between CONFIDENTIAL REPORT and all other versions is a block of offscreen narration by Van Stratten, quoted below, that accompanies four shots of him approaching a rundown house in the snow (shots visible in all the versions). I haven’t been able to determine whether Welles wrote or recorded this exposition; if he did, it seems probable that this was later superseded by the different sort of exposition he employed in no. 3. The end of this narration certainly blunts the power of the film’s most beautiful camera movement, a backward retreat down a dark tunnel of a hallway:

Here I am at the end of the road. Naples,

France, Spain, Mexico, and now Munich.

Sebastianplatz 16. In the attic of this house

lives Jakob Zouk, a petty racketeer, a jailbird,

and the last man alive besides me who knows the

whole truth about Gregory Arkadin. My

confidential report is complete now. My

original fee for this job was $15,000, and it

looks like a little bonus will be tossed in —-

like a knife in my back. But Zouk will get his

first unless I can save him. And then me —- the

world’s prize sucker.

7: The principal public domain version that circulates in this country on video; it may also still be available on film. With the probable exception of the Spanish version, no. 5, and the possible exception of the radio show, no. 1, and the novel,no. 4, it is the least satisfactory version of ARKADIN that we have. But because of its wide availability on video and its frequent showings on TV, it is more than likely the ARKADIN that most Americans know.

For the most part, this qualifies as a clumsily truncated version of no. 6, with many of the significant losses occurring at or near the beginning. Characteristically, the offscreen narration that begins after the credits starts in the middle of a sentence, with Van Stratten on the docks in Naples (which is where no. 4 begins as well).

A Tentative Conclusion:

“Give the Gentleman His Goose Liver”

In his preface to the English translation of André Bazin’s Orson Welles, François Truffaut divides all of Welles’s films into those made with his right hand and those made with his left hand, adding,”In the right-handed films there is always snow, and in the left-handed ones there are always gunshots; but all constitute what Cocteau called the ‘poetry of cinematography.'” ARKADIN is the only Welles film with both snow and gunshots, but I think Truffaut is probably correct in considering it one of the left-handed films. Its moments of poetry are intense and indelible, but the feeling of chaos that it imparts, while fundamental to this poetry, is at times less than adequate to the more prosaic needs of the narrative. Eric Rohmer was right to classify the film as a tale or fable rather than a realistic story or a thriller, and it might be argued that the relative hospitality of French criticism toward unrealistic narrative helps to account for the relative favor ARKADIN has found in French criticism.

Anglo-American critics have generally been put off by the same elements. Dwight Macdonald characteristically complained about the lack of attention paid to Arkadin’s business dealings and the visible artifice in Welles’s makeup for the part; others have seized on the superficial plot resemblances to CITIZEN KANE to berate the film for its incoherence, its performances,and/or its production values.

I share some of these biases, although a few seem misplaced. For all the film’s lack of realism, it still has some validity and interest as a cold war allegory, as James Naremore has suggested. Naremore notes Robert Arden’s “uncanny resemblance to a young, athletic Richard Nixon,” and if one connects this with Arkadin’s resemblance to Stalin -— a resemblance underlined by Arkadin’s habit of killing off former associates and witnesses -— the struggle of the twoover Raina, who might be said to represent Western Europe in the mid-50s, is full of suggestive and subversive possibilities.The fact that Arkadin and Van Stratten are presented as moral equivalents -— older and younger versions of the same unscrupulous lout -— is central to this reading.

Arden’s performance as Van Stratten is commonly singled out for abuse, even by most of Welles’s defenders, but after repeated viewings it seems to me that it’s the unsavoriness and obnoxiousness of the character rather than the performance itself that is responsible for most of this attitude. A comparable syndrome applies to Tim Holt’s George Minafer in THE MAGNIFICENT AMBERSONS:because both characters occupy the space normally reserved for charismatic heroes, we feel we’re supposed to like and/or sympathize with them, and when their respective films make this impossible, we wind up blaming either the actors or Welles’s casting rather than accept the premise that we’re meant to have a difficult time with these people.

This is not to suggest that the performances in ARKADIN are above criticism. I agree that the film has one debilitating performance, but this is given by neither Arden nor Paola Mori (who may be relatively unskilled but still seems quite adequate to the demands the script makes of her). I’m afraid it is given by Welles himself. The falseness of his makeup and the variability of his Russian accent can’t be rationalized by the elusiveness of Arkadin’s character, because no norm is ever established for thesetraits to deviate from. One can accept the film’s premise of presenting us with a gallery of grotesques, but not a title ogre whose face is little more than a Halloween mask. At separate junctures, Arkadin is linked to Neptune and Santa Claus, and at his own ball he hides behind a mask; most of the plot is devoted to uncovering his original identity as a lowlife namedAkim Athabadze. But even this latter phantom, glimpsed in a faded photograph belonging to Sophie, lives more in our minds than Gregory Arkadin does on screen. (Mainly this is because of Sophie herself; she and Zouk wind up providing most of whatever soul the movie has, thanks in large measure to Paxinou and Tamiroff.) Welles appears to have conceived of Arkadin as a tissue of paradoxes, but his own performance, even if it contains some lovely line readings, doesn’t bridge or embrace those paradoxes.At best it only alludes to them.

The character’s silliest moment comes when he informs Van Stratten in a Munich cathedral, “I no longer think of you at all.” Considering the fact that he has already trailed Van Stratten across the Atlantic and back, and followed him not only to and around Munich but even to this very spot, it would be an understatement to call this remark disingenuous. Maybe the missing scenes alluded to by Welles would have provided more of a context for such anomalies; or maybe not. Either way, it’s worth noting the degree to which stubborn irrationality plays a major role in Welles’s work, from Kane and George Minafer to Iago and Othello,from most of the characters in THE LADY FROM SHANGHAI and TOUCH OF EVIL to all of the characters in THE TRIAL.

Perhaps the most underrated feature of ARKADIN is Paul Misraki’s wonderfully evocative and rhythmic score, which sometimes plays even more of a shaping role in the film than the plot, dialogue, or mise en scène. Nostalgia for a lost innocence plays as important a role in ARKADIN as it does in KANE, AMBERSONS, and CHIMES AT MIDNIGHT (where it is also tied to snow), althoughthe site of this innocence is less localized than the nineteenth century or the Middle Ages is in those films (not to mentionTanya’s bordello in TOUCH OF EVIL). Like Arkadin himself, it’s anywhere and everywhere, sometimes where we least expect it.It’s Christmas and goose liver and the last time someone said “Come to bed” to Jakob Zouk. It’s the youths and romantic yearnings of the Baroness Nagel and Sophie, and a scruffy little Salvation Army band in the street. More mysteriously and disturbingly, it’s the sudden, irrational, backward retreat of the camera down a dank tenement corridor, into a dark womb of oblivion.

-— Film Comment, January–February 1992