From the Chicago Reader (January 16, 1998). — J.R.

Jour de fête

Rating **** Masterpiece

Directed by Jacques Tati

Written by Tati, Henri Marquet, and Rene Wheeler

With Jacques Tati, Paul Frankeur, Guy Decomble, Santa Relli, and Maine Vallee.

Every Tati film marks simultaneously (a) a moment in the work of Jacques Tati; (b) a moment in the history of French society and French cinema; (c) a moment in film history. Since 1948, the six films that he has realized are those that have scanned our history the best. Tati isn’t just a rare filmmaker, the author of few films (all of them good), he’s a living point of reference. We all belong to a period of Tati’s cinema: the author of these lines belongs to the one that stretches from Mon oncle (1958: the year before the New Wave) to Playtime (1967: the year before the events of May ’68). There is hardly anyone else but Chaplin who, since the sound period, has had this privilege, this supreme authority: to be present even when he isn’t filming, and, when he’s filming, to be precisely up to the moment — that is, just a little bit in advance. Tati: a witness first and last. — Serge Daney, La rampe (my translation)

The justification for [a] pretense to disengagement derives from our Victorian habit of marginalizing the experience of art, of treating it as if it were somehow “special” — and, lately, as if it were somehow curable. This is a preposterous assumption to make in a culture that is irrevocably saturated with pictures and music, in which every elevator serves as a combination picture gallery and concert hall. The question of whether we can enjoy, or even decipher, the world we see without the experience of images, or the world we hear without the experience of music, seems to me pretty much a no-brainer. In fact, I cannot imagine a reason for categorizing any part of our involuntary, ordinary experience as “unaesthetic,” or for imagining that this quotidian aesthetic experience occludes any “real” or “natural” relationship between ourselves and the world that surrounds us. All we do by ignoring the live effects of art is suppress the fact that these experiences, in one way or another, inform our every waking hour. — Dave Hickey, Air Guitar: Essays on Art & Democracy

The cinema does not show, it previsions… when it is artisanal, it is ten or twenty years in advance; when it is factory-made, it is two or three years. — Jean-Luc Godard

In 1942 Jacques Tati was living in occupied France. The grandson of a Dutch picture framer whose clients included Toulouse-Lautrec and van Gogh, the 34-year-old Tati had played rugby, performed in music halls, and acted in a few short comic films. That year he left Paris with a screenwriter friend named Henri Marquet in search of the remotest part of the country they could find, hoping to escape recruitment as workers in Germany. They finally settled on a farm near Sainte-Sévère-sur-Indre, located in the dead center of France — not far from where George Sand had entertained such houseguests as Chopin, Liszt, Flaubert, and Turgenev — and spent a year or so getting acquainted with the village and its inhabitants.

Three years after Germany’s surrender, Tati and Marquet returned to the village to make a short film, L’école des facteurs (“The School for Postmen”), in which Tati played François, the village postman, who delivers the mail on a bicycle. (François was based loosely on a bit character played by someone else in a comic short Tati had acted in ten years earlier.) L’école des facteurs was Tati’s first directing project, and the following year he and Marquet returned with different cinematographers but the same basic crew to rework and expand the short into a feature, Jour de fête, whose brand-new color process, Thomson-Color, would make it the first French feature in color.

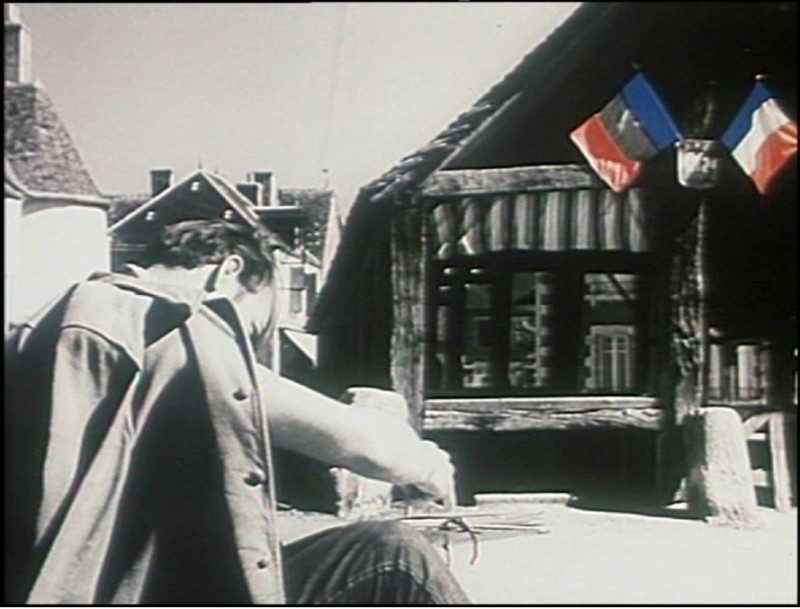

Thomson-Color was a complex experimental process, conceived as an artisanal invention, a homemade alternative to big-studio technology, that could become France’s answer to Technicolor. Aware that he was taking a calculated risk, Tati employed two cameras — one using color and the other, for safety, using black and white — but meanwhile he designed the film’s settings with color in mind, painting many of the house doors in the village a dark gray and dressing most of the villagers in dark coats. The basic idea — part of which he carried over to Playtime almost 20 years later — was to show a colorless village springing to life once holiday caravans arrive with carnival trappings such as painted merry-go-round horses and shiny banners, then returning to drabness once all the festive regalia is carted away.

But Thomson-Color didn’t work, and after Tati found himself unable to print the film in color he resigned himself to releasing it in black and white. He was unable to find a distributor for well over a year, until a successful preview in a Paris suburb inspired him to make a few more revisions, but when the film finally opened in 1949 it grossed ten times its cost and won major prizes in Venice and Cannes, launching Tati’s international reputation. (His next two features, Mr. Hulot’s Holiday and Mon oncle, were even bigger hits — the latter won him an Oscar — and only after Tati sank all his fortune into Playtime, one of the most expensive French films ever made, did he become commercially problematic again. He never fully recovered from the stigma professionally, even after his final two features, Traffic and Parade.)

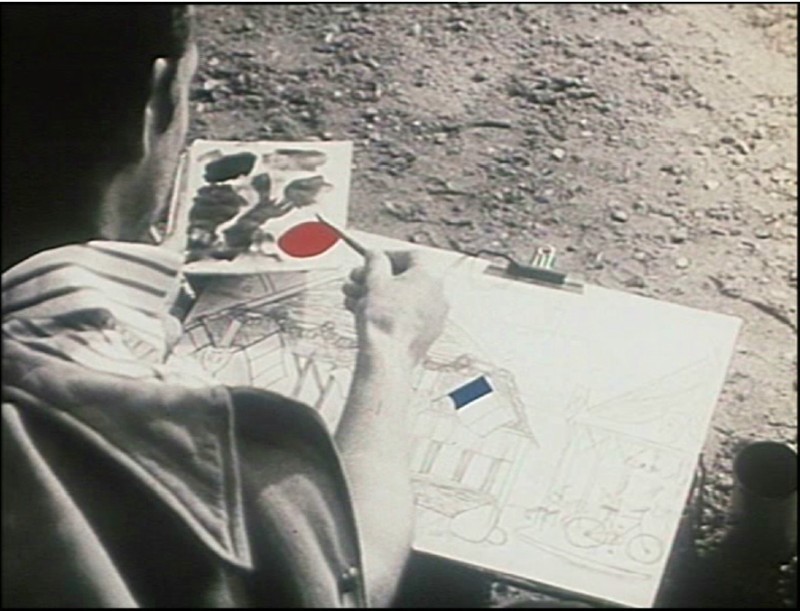

By the 50s Tati was riding high, critically as well as commercially. Shortly before the release of Mon oncle Jean-Luc Godard wrote, “With him, French neorealism was born. Jour de fête resembled Open City in inspiration.” But Tati’s original conception of Jour de fête never fully left him. In 1964 he re-edited the film, remixed the sound track, and colored a few stray visual details with stencils. He even went back to Sainte-Sévère-sur-Indre to shoot new material involving an added character, a young painter who could be seen sketching some of the Bastille Day activities, and Tati was so adept at integrating this new material that the result was seamless. For the next 30-odd years, this was the Jour de fête that everyone saw. Tati extended this talent for revision to some of his other features: over 20 years after Mr. Hulot’s Holiday was first released in 1953 he deftly inserted a brief gag alluding to Jaws, and long after Traffic opened in 1971 he casually slipped in a comic afterthought involving filling-station giveaways.

How an additional character could compensate for the absence of a full-color image is an intriguing puzzle. But Tati’s compositional strategy was an intrinsic part of his genius, making him a worthy grandson of van Gogh’s framer; he was an instinctive artist with an uncanny sense of how seemingly unconnected aspects of a film could connect with one another. (Interestingly enough, this sense corresponds to Carl Dreyer’s stated reason for using four rhyming intertitles in his last feature, Gertrud, intertitles that were later removed. Dreyer had hoped to shoot that film in color and told an interviewer that had he succeeded, those four intertitles — none of which made any reference to color — would have been unnecessary.)

Part of Tati’s legacy is his radical rethinking of how sound relates to image — an idea his peer and contemporary Robert Bresson formulated in different terms. But Tati’s view of color was more than a means of fine-tuning his images; it was part of a wider and more interactive scheme. Because he shot all his films silently and constructed his sound tracks afterward, Tati was able to create an interplay between image and sound that was never a matter of one simply reinforcing the other, and he used color more to accent the image than to enhance it. The Hollywood factory notion of applying sheets or slabs of color — which reaches a kind of apotheosis in colorizing black-and-white features — lies at the opposite end of the spectrum from Tati’s artisanal methods, in which little dabs and touches are applied as discreet counterbalances in the overall composition.

Sophie Tatischeff, Tati’s second child and only daughter and a professional film editor who was born during the shooting of Jour de fête, must have shared this view of her father’s approach when she returned to the color negative of Jour de fête five years after his death, hoping with the help of cameraman François Ede to reconstruct a color print. Her understanding of her father’s conception of color also helps to explain why, once she and Ede finally overcame the technical problems seven years later, she decided to delete the character of the painter and aim instead for a restoration of her father’s original vision.

The full story of this restoration is recounted in a book Ede published in France three years ago, a week before the successful French release of the film in color. I haven’t been able to read the book, but judging from various other accounts of the patience and technical wizardry involved, it’s a story of artisanal pride and determination triumphing over impossible odds. In some ways it recalls Jour de fête itself, which chronicles the bumbling efforts of a village postman to approximate the streamlined technology and speed of the American postal service after glimpsing a hyperbolic French newsreel on the subject. (A bent old lady with a goat who serves as the village’s spokesperson and guides us through some of its inner workings — a bit like the stage manager in Our Town — eventually concludes that François is better off doing what he’s always done than trying to top the Americans, cautionary words that reflect ironically on Tati’s misadventures with Thomson-Color.)

One might argue that Tatischeff and Ede’s work isn’t a “pure” restoration insofar as Tati himself was never able to edit his own color footage. But Tatischeff, who worked with her father on the editing of half of his features, was probably more qualified to carry out this task than anyone else alive, and she had two previous versions of Jour de fête edited by her father to guide her decisions. What emerges is not so much a “new” Tati film as an old one seen properly for the first time, in the full flavor of its own period.

None of this would matter quite as much, of course, if Jour de fête weren’t already a masterpiece by one of the key figures in the history of cinema. The film has always been a charming populist favorite — at least when people could discover films on their own, without expensive ad campaigns to limit their choices. But its restored color version is doubly precious: this is color that truly looks like 1947 — not films of that period so much as 1947 itself — and its bucolic postwar euphoria, not to mention its affection for interactive village life, has all the fragrant perfume of a time capsule. (For comparably paradisiacal views of village life mixed with dollops of wry social criticism, I can only think of a few John Ford items, like Judge Priest, The Sun Shines Bright, and The Quiet Man.) Thomson-Color looks distinctly different from every other color process, and the fact that we have virtually no other color record of French life during the 40s gives Jour de fête the force of a revelation.

Formally, Jour de fête offers a rough sketch of most of the ideas Tati would flesh out in his later features (reaching their climaxes in the black-and-white Mr. Hulot’s Holiday and the color Playtime). There’s the comic interplay between foreground and background details, such as our first introduction to François the postman on his bike, dodging an invisible bee in the background while a hay mower in the foreground tries to decode his curious zigzagging movements — until the same bee menaces the mower a moment later. There’s the clean detachment of the images from the sound track — the latter a beautiful and highly selective blend of sound effects, ambient noises, and dialogue, comprising a kind of musique concrète (though there’s more dialogue than Tati would ever use again). This separation of sound from image allows for a certain counterpoint between the two, most apparent in the hilarious pantomime of flirtation between carnival worker Roger (Guy Decomble) and villager Jeannette (Maine Vallée) to the accompaniment of dialogue from an American western playing inside an adjacent tent. (This flirtation recurs in various forms throughout the picture, and the fact that Roger is married gives the romantic longings a certain naughtiness that Tati would omit from his later movies; in more ways than one, this is his most typically French film.)

Jour de fête amounts to a kind of stylistic manifesto as well. Most of Tati’s work derives from observation rather than pure invention, inflected by the aesthetic and poetic properties of music, painting, and dance (which is where the invention comes in); everyday details are the basic unit of this enterprise rather than incidents designed to advance a plot. This is why Tati’s films are generally better appreciated by ordinary viewers than by critics and specialists, who tend to be more rigid about what films should be, storywise and otherwise. (Twenty years ago, my film class students were far more responsive to Playtime than were critics like Pauline Kael and Andrew Sarris, who declared themselves bored and alienated.) Tati’s observation is tempered and structured by an aesthetic-poetic imagination and by the perception that all of us, as critic Dave Hickey suggests, are living continuously inside a complex work of art that we call the world, and that perhaps only another work of art can teach us to appreciate what’s right in front of us.

Thematically as well, Jour de fête offers a kind of blueprint to Tati’s subsequent oeuvre, despite the fact that it offers the only rural setting in his work apart from the middle section of Traffic. The enormous impact of the French newsreel about American postal delivery — not only on François but also on the other villagers, who mercilessly mock François’ relative inefficiency — initiates a complex and ambivalent critique of technology in general and Americanization in particular that informs the remainder of Tati’s work, apparent even in the bilingual titles of his last three films. (Ironically, the implied critique of French versus American mail delivery — however applicable to a sleepy village in the late 40s — was directly contradicted by my own experience living in Paris in the early 70s, when I could practically set my watch by the three prompt deliveries made to my building every weekday and the two made every Saturday.) The combined threat and promise of the “new,” inextricably tied up with an internal debate about America, is discernible in the tacky suburban architecture (complete with Japanese garden) in Mon oncle, the invading American tourists in Playtime, and the all-purpose camper-trailer in Traffic. And Jour de fête remains not just “a little bit” ahead of its time (according to Serge Daney) or “10 or 20 years” (according to Godard’s formula) but a full half century in its perception of what mass culture and technology mean to the quiet life of a remote village. As American and Japanese investors circle mainland China, Jour de fête might serve as a relevant commentary on the day after tomorrow.

To appreciate Tati’s ambivalence about this matter in all its complexity, one has to see Jour de fête in a specifically postwar context, where genuine gratitude toward Americans for helping to liberate France weighed against the cultural and economic bullying imposed by the Marshall Plan — which included a quota of Hollywood pictures, some of them in Technicolor. (Late in the film, a cycling François manages to run two American MPs off a country road by pretending to bark orders over a telephone, in a parody of American-style efficiency.)

Most of the preceding fails to do justice to the physical comedy in Jour de fête, which harks back to the purity of silent comedy in its grace and the beauty of its natural surroundings. (There’s even a cross-eyed carnival worker who seems inspired by Ben Turpin, and the bucolic splendor of the countryside offsets Francois’ frantic pedaling as he makes his rounds.) It’s a perfect movie for children — some of whom catch certain details that adults are prone to miss — and seeing it on a big screen can be as enveloping and as transporting an experience as many of the better Disney animated features.

Yet judging by the total indifference of the American mainstream toward the restored Jour de fête — a lack of interest dictated by the film’s U.S. distributor, Miramax, which has brought the film to America only reluctantly, without ads, and for no longer than a week at only a handful of locations — it is much more culturally serious these days to spit on the grave of Henry James with a slimy soft-core travelogue like The Wings of the Dove. Because of the money and muscle Miramax has expended on this cheesy factory product, it hasn’t had any trouble gaining the recognition and (in most cases) reverence of Time, Newsweek, the New Yorker, Entertainment Weekly, New York, the New York Times, the New York Review of Books, the TV reviewers, and numerous other media players, none of which has shown a flicker of interest in the color Jour de fête.

It’s an axiom of our Reaganite culture that businesses can do whatever they want with movies and that the press should rubber-stamp these decisions on the basis of ad budgets. Miramax is of course perfectly entitled to deem this crowd pleaser unmarketable and unworthy of anybody’s attention — though luckily this also means that they haven’t bothered to recut it, which they generally do only with films that they “believe in.” What I object to, rather, is the mass media’s implied insult to the audience at large by kowtowing to Miramax and refusing to acknowledge any alternatives that could possibly merit anyone’s attention, even when they’re as irreplaceable as the restored Jour de fête. In a society where price tags have become the only cultural credentials, Tati’s film couldn’t even pass muster at a garage sale. But for this week only, at the Music Box, you can still inhabit a world where artisans shine.